On April 5, 1945, heavy rain fell on the headquarters of the Japanese Navy’s Hoshi Command. The staff officers of Admiral Semu Toyota…

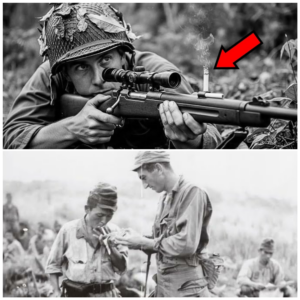

August 14th, 1944. 06 45 hours. Guam, Mariana Islands. The tropical sun broke over the jungle ridge with the sudden intensity that characterized…

June 4th, 1944. Somewhere in the French countryside near Khn Normandy, the morning fog clung to the rolling fields like a protective blanket,…

December 9th, 1944 0530 hours, Herkin Forest, Germany. The match flared briefly in the frozen darkness as Sergeant William Bill Ashworth struck it…

February 26th, 1945. Dawn breaks over Eojima’s black volcanic beaches. Private Wilson Watson grips the 20 lb Browning automatic rifle, the gun every…

On the morning of October 23rd, 1942, at the mouth of the Matanakau River on Guadal Canal, a marine heavy machine gun section…

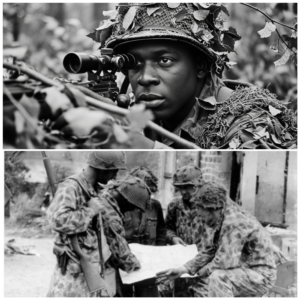

November 14th, 1943. 0530 hours. Bugenville Island, Solomon Islands. Staff Sergeant Thomas Arthur Caldwell pressed his body deeper into the volcanic soil. The…

There are specific moments in life that change you forever in the blink of an eye. They are these shattering instants where everything…

I rushed through the hospital corridor, barely able to breathe as I clutched my purse against my chest. The call had come only…