The German soldiers who had surrendered in North Africa, France, or Italy expected a grim fate once captured. For years, Nazi propaganda had told them terrifying stories of what awaited those unlucky enough to fall into enemy hands, forced labor in mines, beatings from guards, starvation rations, and endless humiliation. Many of the men had grown up on such stories, and their imaginations painted dark pictures as they were lined up, disarmed, and marched into captivity. Their eyes scanned the American trucks and guards, noting the discipline, but also the casualness with which the Americans treated their captives.

Instead of snarling or lashing out, the soldiers offered cigarettes, water, even a joke or two. Still, the prisoners remained cautious. This had to be some trick. They assumed the true cruelty would reveal itself once the long journey to America ended. The transports themselves were another surprise. Instead of being crammed into filthy cattle cars with barely any air, many found themselves aboard proper ships or trains, guarded but not abused. They were given food, white bread, meat, coffee, and allowed to rest.

For men raised under wartime scarcity, such treatment was baffling. They whispered among themselves, “Why waste food on the enemy? Why show kindness to men who had tried to kill them?” The answers eluded them, and suspicion lingered. Perhaps the Americans wanted to keep them healthy for brutal labor. Perhaps this was a trick before harsher punishment began. Some even believed they were being fattened for medical experiments so deeply ingrained were the horror stories back home. As they crossed the Atlantic, staring at the vast ocean that separated them from their homes, a heavy silence often filled the decks.

These men had trained to conquer Europe, to follow Hitler’s commands, to see themselves as the chosen warriors of a thousand-year Reich. Now they were prisoners, powerless, and uncertain of what future awaited. America was not a land they had imagined visiting under such circumstances. Many thought of America only as a distant industrial powerhouse, a place of skyscrapers, jazz music, and Hollywood films. Yet here they were, not as tourists or conquerors, but as captives. The first glimpses of the American coastline stirred a mix of dread and curiosity.

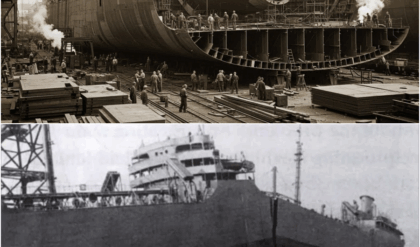

Towering harbors, sprawling cities, and endless rows of factories confirmed the stories of American industrial might. The prisoners were struck by the sheer size of everything, the cranes, the ships, the highways. Even before arriving at their designated camps, they sensed the vastness of the United States and the resources at its disposal. To German soldiers who had fought desperately with dwindling supplies, the contrast was painful. Once loaded onto buses and trucks, the journey inland began. Through the windows they saw landscapes unlike anything in Europe, wide open fields stretching farther than the eye could see, endless roads and small towns with neon signs and gasoline stations.

Children waved as convoys passed, and locals sometimes gathered to glimpse the enemy soldiers. The prisoners, in turn, watched with fascination at the abundance of goods and comfort in ordinary American life. If this was the land of their captives, what did that say about the war they had fought? The questions grew louder in their minds. Arriving at the camps was another revelation. Rows of clean barracks, mess halls, medical stations, and even recreation areas greeted them. They expected barbed wire, yes, but behind it there were organized facilities rather than squalid prisons.

Instead of being whipped or starved, they were processed efficiently, assigned bunks, and given uniforms. Some still suspected cruelty hidden behind the orderliness. Others began to wonder if perhaps America’s strength lay not only in its weapons, but in its ability to treat even its enemies with a strange kind of humanity. This was only the beginning. In the months ahead, German prisoners would discover more shocks, more contradictions, and more moments that challenged everything they thought they knew about their captives.

Yet even now, as they lay in their bunks that first night, full stomachs and exhaustion pulling them to sleep, whispers moved through the barracks. If this is a prison camp, what comes next? None of them could have guessed that the next surprise would involve the flickering glow of a movie screen. The first days inside the American camps were a study in contrasts. The German prisoners had braced themselves for shouting guards, degrading punishments, and endless hunger. Instead, they were confronted with order and routine.

Roll calls were strict, but they were not accompanied by beatings. The guards carried rifles, but often stood at ease, chatting with one another rather than barking orders. The camp fences were topped with barbed wire, yet the air smelled of cooked meals drifting from the messaul. Inside the barracks there were cs lined neatly, mattresses stuffed with real bedding, and even stoves for warmth in colder seasons. It was hardly luxurious, but it was far from the nightmare they had imagined.

Meals shocked them most of all. Prisoners had expected thin soups or stale bread, the kind of rations many German civilians were forced to endure during the war. Yet trays carried into the dining halls contained hearty portions, meatloaf, potatoes, beans, coffee, milk, even fruit on occasion. The abundance seemed impossible. Men who had fought in frozen fields on a diet of black bread and watery broth now sat with plates that looked almost like home-cooked meals. Some initially refused to eat, convinced the food must be drugged or contaminated, but hunger overcame suspicion, and soon disbelief turned into quiet gratitude.

Rumors spread. They feed us better than our own army did. Beyond food, the camps contained unexpected touches of normal life. The Red Cross delivered packages with soap, toothpaste, even writing materials. Medical clinics offered treatment for wounds and illnesses. Guards occasionally handed out cigarettes, and some camps even had small libraries stocked with books and newspapers. The prisoners were stunned to discover they were allowed to write letters home, though carefully censored. The very act of putting pen to paper and hearing back from family felt like a miracle, restoring a link to the world they thought lost.

Discipline existed. Of course, escape attempts were punished and curfews were enforced. Yet the punishment was often confinement rather than brutal violence. The Americans seemed more concerned with maintaining order than inflicting cruelty. This attitude unsettled the prisoners. They had been taught that the Americans were ruthless, decadent barbarians, incapable of discipline or fairness. Instead, they found themselves living under rules that, while strict, carried a strange sense of fairness. The camps were designed to contain men, not to break them.

Even the physical surroundings baffled them. Many camps were located in rural areas of the American South, Midwest, and West. Through the fences, the prisoners could see endless farmlands, forests, and small towns. Farmers sometimes worked nearby fields, and in some places, prisoners were sent out under guard to help with agricultural labor. They were shocked to see American civilians treating them not with hatred, but with a curious indifference, as if they were just another group of workers passing through.

Children sometimes waved at them. Women occasionally brought pies or bread to guards, and the sight of such casual normaly unsettled men who had believed America was nothing but a land of hostile enemies. At night, when the barracks grew quiet, many whispered about the strange situation. “Is this really captivity?” one would ask. Another would reply, “Maybe they are preparing us for something worse. ” Yet others began to suggest a more dangerous thought. Maybe what we were told about America was wrong.

Seeds of doubt sprouted in these quiet conversations. For men trained to see the world in absolutes, the Reich as the pinnacle of civilization and the Allies as barbaric, the everyday kindness and comfort of camp life threatened to erode the certainty that had once seemed unshakable. Still, no one could have foreseen what would come next. The Americans, it seemed, were not content with providing food, shelter, and safety. They had something else in mind, something so unexpected, so strange that many German prisoners thought it was a trick of the imagination.

They would soon gather in large halls or makeshift theaters, and for the first time since leaving home, they would be transported far beyond the fences of their camp, not by escape, but by the shimmering images projected onto a movie screen. The rhythm of camp life soon settled into routines that both comforted and confused the German prisoners. Days began with roll call, followed by meals that continued to astonish men used to thin rations back home. Work details filled the hours for many, often assisting on nearby farms or helping maintain the camp itself.

For soldiers who had spent months in muddy trenches, hauling hay bales or repairing fences under the American sun felt almost like a strange holiday. They were guarded, yes, but the work was reasonable, the pay symbolic yet present, and in return they were treated more like laborers than condemned enemies. Some even joked quietly among themselves, “If this is prison, what does freedom look like?” Leisure hours proved even more disorienting. Instead of endless punishment drills or silence, there were spaces for recreation.

Soccer fields and volleyball courts appeared inside the fenced compounds with prisoners forming teams and staging matches. American guards sometimes watched, even cheered, and occasionally joined in. There were chess boards and card games in the barracks, and those who could draw or carve were allowed to pursue their crafts. A few camps organized small orchestras with instruments provided by the Red Cross, their music drifting over the wire in the evenings. The atmosphere was surreal. Men who had fought bitterly in North Africa and Europe now spent their evenings playing Mozart or laughing over card games as if the war existed in some faraway world.

Clothing too defied expectation. Issued camp uniforms were simple but clean with sturdy shoes and coats for the colder months. Compared to the ragged liceinfested gear some had worn in battle, it was a blessing. Hygiene facilities offered soap showers and even barber services. German soldiers who had marched through villages reduced to rubble were astonished at the basic dignity afforded them here. Some whispered nervously, “Why are they treating us so well? What do they want from us?” Suspicion lingered, but the reality remained undeniable.

Their American capttors seemed more interested in keeping them healthy than in breaking them. Meals continued to provide endless conversation. The availability of white bread, real butter, meat, and milk stunned men who knew their families back home struggled to find potatoes and horsemeat. Rumors circulated that prisoners were fed nearly the same rations as American soldiers themselves. Some even felt guilty writing home about their meals, knowing their mothers, wives, and children lived under rationing and bombing. Yet the abundance also planted new doubts.

How could Germany possibly win against a nation capable of feeding its enemy this well? Entertainment came in smaller forms at first. Censored newspapers allowed into the camp revealed snippets of a world outside. Many prisoners were surprised by how openly American papers criticized their own government and military. This freedom of expression contrasted sharply with the rigid propaganda machine of the Reich. Books in camp libraries ranged from classics of German literature to American novels translated into German. Reading Mark Twain or Jack London by Lamplight in a barracks seemed almost unreal.

Slowly an unexpected picture of America emerged. a place of contradictions, but not the barbaric wasteland they had been taught to hate. Yet the greatest shock was still on the horizon. In the evenings, when the camp’s routine slowed, and the men gathered with restless energy, the Americans began offering something beyond soccer fields and books. Prisoners were summoned to large halls or open areas. A projector was set up. A white sheet hung across a wall. And soon, beams of light cut through the darkness.

At first, the Germans did not believe what they were seeing. Moving images larger than life, flickered into view. The Americans were letting their enemies watch movies, not propaganda, not lectures, but actual Hollywood films. For men trapped behind wire, it was as if a portal to another world had suddenly opened. The disbelief that had begun with food and comfort now reached new heights. Could this truly be happening? When the first reels began to spin inside the camps, silence fell over the gathered prisoners.

They had expected speeches, lectures, perhaps even heavy-handed propaganda designed to humiliate them. Instead, the flickering light revealed cowboys galloping across dusty plains, comic actors stumbling through absurd misadventures, and glamorous stars dancing and singing in ways the soldiers had never seen. The shock was immediate. For many, this was their first time experiencing American cinema at all, and the contrast to the grim propaganda reels of the Reich was overwhelming. Instead of military parades and furer speeches, there was laughter, music, and fantasy.

It was as if a piece of another universe had been delivered through the barbed wire. The guards, standing at the edges of the makeshift theaters, watched with a mix of amusement and curiosity. They saw the hardened faces of enemy soldiers soften into smiles, chuckles, and at times open laughter. Some prisoners clapped during slapstick scenes, while others sat wideeyed at the sheer scale of the productions. For German men who had grown up under strict discipline and years of war, the sudden immersion in stories of adventure and romance felt intoxicating.

Hollywood had crossed the fences and reached them where no weapon could. Not every reaction was simple amusement. Some soldiers grew uneasy at the casual freedom portrayed on screen. They saw men and women openly flirt, workers criticize their bosses, and poor characters rise above misfortune through wit and charm. Such scenes contradicted everything they had been told about America, that it was a land of corruption, chaos, and decay. Instead, they glimpsed a society where even ordinary people seemed to have dreams and dignity.

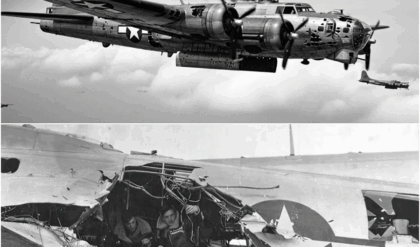

This contradiction gnawed at them in the dark as the projector clicked away. Could it be that their leaders had lied about the enemy all along? News reels added another layer of surprise. While carefully chosen, they often showed the American war effort, bustling factories, fleets of ships, or soldiers marching with confidence. For prisoners who knew firsthand how desperate supplies had become in Germany, these images were almost unbearable. The sheer abundance of machinery, the rivers of tanks rolling off assembly lines, the crowds of well-fed workers, all served as reminders that the Reich could not possibly outproduce its enemy.

Yet even these revelations were delivered not with cruelty, but almost casually, hidden between scenes of comedies and musicals. The Americans seemed to understand that the power of cinema lay not in lectures but in the steady drip of images that undermined old beliefs. What astonished the prisoners most was that attendance was voluntary. No one forced them to sit before the screen. They could choose to remain in their barracks to play cards or write letters instead. Yet the halls quickly filled whenever the projector was set up.

Word spread rapidly after each screening. Tonight they are showing another western or tomorrow a comedy. Men who once marched under swastikas now found themselves looking forward to evenings of American entertainment. Some began to keep mental lists of favorite actors or genres comparing notes with fellow prisoners. Others admitted with a mix of shame and wonder that for a few hours they forgot they were captives at all. In the glow of the screen, something subtle shifted. The barbed wire faded into the background, and the war felt distant.

The men were no longer just prisoners of conflict. They were spectators of stories larger than themselves. The Americans, whether intentionally or not, had given them a powerful gift, a window to a world of imagination and humanity that no prison wall could fully contain. And as the credits rolled and the lights came up, the disbelief lingered. They could not understand why their enemies allowed such indulgence. Yet deep down they knew they would never forget the nights when Hollywood came to the camps.

The nights of film screenings became a rhythm that prisoners clung to with quiet anticipation. Word would ripple through the barracks when the guards announced another show, and men who spent their days hauling lumber, repairing fences, or working in fields, suddenly found themselves hurrying through dinner just to secure a good seat in front of the projector. For those trapped behind barbed wire, these evenings offered an escape no tunnel could provide. The flickering light on the screen dissolved the fences, if only for 2 hours.

The men leaned forward on benches or sat cross-legged on the floor, staring into a world that felt brighter, freer, and more alive than the one they had left behind in Germany. The choices of films astounded them. Comedies featuring Charlie Chaplan or the Marx Brothers sent ripples of laughter through rooms filled with men who had not laughed freely in years. Westerns with their sprawling landscapes and clear battles between good and evil felt like morality tales painted against a backdrop larger than life.

Musicals with their dance numbers and glittering costumes produced a different kind of shock. the sheer extravagance of a country that could afford to turn life into song while fighting a global war. And then there were romances where women with dazzling smiles spoke lines filled with wit and independence. German soldiers who had been raised under rigid gender roles sat in stunned silence at these portrayals of confident women so different from the carefully controlled images in Nazi films. For some, the experience bordered on dangerous fascination.

They found themselves discussing favorite actors during work details, imitating comedic lines, or humming melodies long after the credits had rolled. To enjoy enemy culture so openly felt almost like betrayal, yet the human pull of entertainment was too strong to resist. Even officers who tried to discourage too much enthusiasm could not deny the magnetic pull of the screen. When the lights dimmed, rank vanished. Hardened veterans sat beside teenage recruits, all equally absorbed by the world unfolding before them.

The contrast to the films of the Reich was stark. In Germany, cinema had been a weapon, a tool to glorify Hitler, the party, and the eternal struggle against enemies. Stories were rigid, predictable, heavy with ideology. Here, the Americans seemed almost careless in their freedom. Films could mock authority, satarize the wealthy, or celebrate the triumph of ordinary people. The prisoners whispered to one another, “How could such chaos produce a nation strong enough to fight across continents?” Yet the more films they saw, the more they realized that this chaos was not weakness.

It was a kind of vitality they had never known. Some men began to write home about the screenings, though censorship prevented full descriptions. We are shown strange entertainments, one hinted in a letter, that make us forget for a while where we are. Families back in Germany surviving on ration cards and state controlled news could scarcely imagine such a thing. The very idea that captured soldiers might watch American movies sounded absurd. Yet within the camps the screenings became one of the most talked about privileges, almost a currency of morale.

And so the disbelief deepened. The German prisoners taught to expect cruelty found themselves instead immersed in laughter, music, and stories. It was not freedom, but it was a taste of something dangerously close to it. Each night at the movies left them both grateful and unsettled, wondering why their enemies allowed such indulgence, and what effect it might be having on their own loyalties and identities. The screen was no longer just entertainment. It was a silent teacher reshaping how they saw the world and themselves inside the wire.

As weeks turned into months, the nightly screenings began to shape something far more profound than amusement. The prisoners found themselves talking endlessly about what they had seen, analyzing not just the plots, but the values behind them. A comedy might spark debates about American humor, which seemed rooted in mocking pompous authority and celebrating underdogs. A western would ignite conversations about freedom, justice, and the vast open landscapes that symbolized possibilities far beyond war. Even romances, dismissed at first as frivolous, revealed something unsettling.

The open display of affection, independence of women, and casual social interactions suggested a society far less rigid than the one they had left behind. Slowly, imperceptibly, the films were chiseling cracks into the hardened beliefs drilled into them by years of Nazi indoctrination. The guards noticed the transformation. The hostility of new arrivals, once sharp and simmering, dulled over time. Prisoners who had shouted about eventual German victory, now grew quieter, their certainty shaken. Instead of dreaming about returning to a triumphant Reich, many whispered about whether such a life of abundance and freedom could truly exist beyond the fences.

The films planted images of supermarkets overflowing with goods, of ordinary Americans laughing in theaters, of music echoing in dance halls. These images stood in brutal contrast to the ration lines and bombed out cities the prisoners knew awaited them back home. Even the most disciplined among them could not fully resist. Officers who tried to frame the films as mere propaganda struggled when their men pointed out how different these reels were from the stiff productions of Gerbal’s ministry. If this is propaganda, one soldier muttered after a musical, then it is the most beautiful propaganda I have ever seen.

Another answered, perhaps it is not propaganda at all, but simply how they live. These conversations revealed the dangerous potential of entertainment. It bypassed ideology and touched directly on human longing. The Americans may not have intended it as psychological warfare, yet the effect was undeniable. The more the prisoners laughed at American comedies, the harder it became to see the United States as a faceless enemy. The more they admired the resilience of characters overcoming hardship, the more they questioned the German claim that only discipline and obedience led to strength.

Films about communities uniting, about individuals defying corrupt leaders, or about ordinary people achieving greatness all challenged the authoritarian world view they had carried into captivity. For younger soldiers, the movies were intoxicating. Teenagers who had been raised on Hitler youth rallies saw in Hollywood a different kind of heroism. Not bound to uniform and flag but to individuality and courage. They scribbled names of actors in notebooks, learned English phrases from repeated screenings, and even tried to imitate the swagger of American cowboys.

What began as mere entertainment turned into cultural fascination. Letters home, though censored, hinted at these shifts. Families reading between the lines sensed that captivity in America was not the grim ordeal they had expected. Some prisoners described how the films reminded them of peace time, of moments in their youth before war consumed everything. Others confessed privately to comrades that they dreaded leaving the camp one day, fearing they would never again see such abundance, such freedom, such light-heartedness. The disbelief of the first screenings gave way to something more lasting, a quiet transformation of world view.

Barbed wire still enclosed them, but in their minds horizons were expanding. The glow of Hollywood had seeped into their thoughts, undermining old certainties. They had entered the camps as soldiers of the Reich. Now slowly they were becoming men who could not look at the world in the same way. The Americans had discovered that cinema could soften even the hardest of enemies, not with force, but with story. As the war ground toward its inevitable conclusion, the prisoners began to imagine what life would be like once the gates finally opened and they were shipped back to Germany.

For many, the thought of returning home filled them with as much dread as hope. Letters and Red Cross updates made it clear that their families were enduring bombings, shortages, and devastation. cities they had grown up in were reduced to rubble, and the once proud Reich was shrinking by the day. The contrast between the reality of home and the strange comforts of captivity in America weighed heavily on their minds, and among the stories they would carry back, none seemed more unbelievable than the nights they spent watching American movies.

When the war ended in Europe and repatriations began, groups of men boarded ships once more, this time to cross the Atlantic in the opposite direction. They crowded on decks, staring at the vast ocean, knowing they were leaving behind not just America, but the peculiar life they had lived behind its barbed wire. They talked in hushed tones, almost embarrassed about the things they would miss. The food, the soccer matches, the cigarettes, and above all, the glow of the movie projector.

“No one back home will believe it,” one man said. “They’ll think we’ve gone mad.” Another answered, “How can we tell them we laughed at American comedies while our cities burned?” The dilemma was real. to speak openly about their camp experiences risked disbelief or even accusations of disloyalty. Yet the stories spread anyway. In villages across Germany, returning prisoners whispered of their surreal captivity. They described nights when thousands of men sat together in silence, watching Clark Gable or Ginger Rogers light up the screen.

They told of musicals filled with color and energy, of cowboys galloping through endless landscapes, of romances that seemed to embody a freedom they had never known. Families listened in astonishment, struggling to imagine their sons and husbands laughing at films while the Reich collapsed around them. For many civilians, the accounts sounded like fantasy, or worse, deliberate lies meant to diminish the suffering endured at home. Still, the memories clung to the men who had lived them. Some former prisoners admitted that those screenings altered how they thought about the world.

They could no longer accept the simple dichotomy of good Reich versus evil allies. They had seen another side of America. Not just its military might, but its culture, its humor, and its ability to turn life into art. Even as they walked through ruined German streets and tried to rebuild their lives, the glow of the screen followed them. It became a quiet marker of how much their worldview had shifted. The most striking part of their stories was how ordinary the screenings seemed to the Americans.

Guards set up projectors casually as though letting prisoners watch Hollywood films was nothing remarkable. To the Germans, however, it had been extraordinary, a surreal inversion of everything they thought captivity would be. Some described it as the moment they realized America was not only a superpower of machines and weapons, but also a superpower of imagination. When asked later in life about their time in American camps, many veterans skipped over the details of labor or discipline. Instead, their voices softened when they spoke of cinema nights.

For them, those hours had been more than distraction. They were a reprieve from the weight of war, a glimpse of a different kind of future, and a memory that lingered long after the barbed wire was gone. In the years that followed, the memory of cinema knights inside American prison camps became one of the strangest legacies of the war for those who had lived it. For many former PWs, the image of sitting shoulderto-sh shoulder with comrades watching American films under the watchful eyes of guards was etched as deeply as the battles they had fought.

It was a paradox that they carried with them. They had been enemies of America. Yet, it was America that had allowed them moments of joy and humanity in the darkest chapter of their lives. When historians later interviewed these men, the subject of movies came up again and again. Some laughed about how they had memorized lines from comedies or fallen in love with Hollywood actresses they had never expected to see on screen. Others spoke more seriously, admitting that the films had been their first glimpse of another world, one that contradicted the bleak picture painted by Nazi propaganda.

They remembered how those reels revealed a society that valued laughter, creativity, and individuality, qualities that had been nearly suffocated under the rigid order of the Reich. The impact went beyond individual memories. In post-war Germany, especially during the years of reconstruction, American culture began to flow more openly into the country. Former PWs often became unintentional ambassadors telling family and friends about the films they had seen while in captivity. They described the humor, the music, the larger than-l life stories, and the sheer vitality of Hollywood.

For younger Germans hungry for something beyond the ashes of defeat, these accounts fueled curiosity about the United States. The Marshall Plan may have rebuilt infrastructure, but it was stories like these, of laughter behind barbed wire that rebuilt imaginations. Some veterans even admitted that their later openness to democracy and western ideals could be traced back to those nights in captivity. While no film single-handedly changed a world view, the steady exposure to American cinema softened hardened soldiers in a way bullets never could.

The seeds planted in those makeshift theaters sprouted years later when former enemies found themselves part of a new West Germany aligned with the very nation they had once fought against. In that sense, the glow of the movie projector had been a quiet, unexpected instrument of reconciliation. Yet disbelief never fully faded. Even decades later, former prisoners would chuckle and shake their heads when recounting the experience. We were the enemy, they would say, and they let us watch movies.

To them, it remained a symbol of America’s overwhelming confidence and abundance. a country so powerful it could afford to entertain its captives. It was also perhaps a reflection of something deeper. The idea that culture and imagination could be weapons just as potent as guns and tanks. The legacy of those screenings lived on not only in memory but in the cultural bridge they helped build. Men who had once marched for Hitler carried home a secret story of nights when laughter and music filled prison halls.

They told their children and grandchildren about how they had seen America not through the sights of a rifle but through the glow of a movie screen. And in that strange flickering light they discovered that even in captivity humanity could survive and even in war the seeds of peace could be planted.