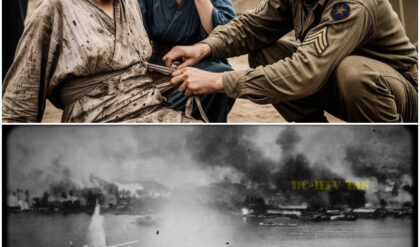

December 7th, 1941. Pearl Harbor burns and Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Casey stares at his Pacific War maps in stunned silence. Every red pin marks where America desperately needs airfields, dozens of coral at holes, jungle clearings, hostile beaches. His calculations are brutal. 40,000 tons of concrete, 300 men, 45 days minimum per runway. At that pace, the war will end before half the needed air strips exist. 6 months later, Baton Peninsula. American engineers abandon their concrete runway halfbuilt as Japanese forces close in.

6 weeks of backbreaking work, 200 tons of concrete, all worthless because they ran out of time. But in a Pittsburgh steel mill, metallurgist Gerald Gilich sketches something impossible on his lunch napkin. Perforated steel sheets with holes. His colleagues burst into laughter. Jerry, airplanes need solid surfaces, not Swiss cheese. Army generals agreed. Mr. Groich, you’re proposing to land a 15-tonon bomber on metal sheets full of holes. This is aircraft safety, not bridge building. What they didn’t understand was that Groich’s crazy idea would let American pilots land anywhere on Earth within 24 hours, not despite the holes in his steel because of them.

The mathematics behind one engineer’s impossible solution was about to change warfare forever. December 7th, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor had ended 6 hours ago, but Lieutenant Colonel Hugh J. Casey still stood motionless in his Honolulu headquarters, staring at the Pacific theater map spread across his steel desk. Smoke from the burning harbor drifted through his office windows, carrying the acrid smell of aviation fuel and twisted metal. Red pins dotted the map like a rash. Wake Island, Midway, Guadal Canal, dozens of coral at holes and jungle clearings where America would need airfields if it hoped to fight back across 6,000 m of ocean.

Casey pulled out his slide rule and began calculating. Each concrete runway required 40,000 tons of cement, sand, and aggregate. 300 skilled construction workers, 45 days minimum, assuming perfect weather and no enemy interference. He moved his pencil down the list of strategic locations, multiplying by the projected timeline. The mathematics were unforgiving. At current construction capacity, the Army Corps of Engineers could complete perhaps 12 major airfields per year. The Pacific held over 60 critical positions where air power would determine victory or defeat.

His aid, Major Robert Stevens, entered carrying fresh intelligence reports. Sir, Navy estimates we’ll need operational air strips at 37 forward positions within 18 months to support Admiral Nimitz’s offensive plans. Stevens sat down the folder and glanced at Casey’s calculations. How many can we realistically build in that time frame? Casey tapped his pencil against the map. 18, maybe 20 if we’re lucky with supply convoys, and the Japanese don’t interfere with our construction sites. The implication hung in the air like the Pearl Harbor smoke.

America would lose the Pacific War because it couldn’t build runways fast enough. By February 1942, Casey’s worst fears were materializing. The Baton Peninsula evacuation had become a nightmare of abandoned construction projects. American engineers destroyed their half-completed concrete runway rather than let it fall into Japanese hands. 6 weeks of grueling labor, 200 tons of precious concrete shipped 8,000 mi from California, reduced to rubble by army demolition charges. The Japanese advance had simply moved faster than American construction capacity.

Casey’s field reports painted the same story across the Pacific. On Wake Island, marine engineers had poured concrete foundations for a bomber strip when the Japanese assault began. The runway existed only in blueprint form when the garrison surrendered. At Clarkfield in the Philippines, a massive concrete expansion project lay 70% complete, useless without the final month of finishing work that would never come. The pattern was devastating and consistent. Concrete construction demanded perfect conditions, stable supply lines, secure perimeters, uninterrupted work schedules.

War provided none of these luxuries. Traditional runway engineering perfected during two decades of peacetime airport construction proved catastrophically unsuited to combat conditions where strategic positions changed hands weekly. Casey found himself questioning everything the Army Corps had taught him about airfield construction. His engineering professors at West Point had drilled into him the fundamental principle. Runways must be permanent, stable, and built to withstand decades of heavy aircraft operations. But what good was a runway that took months to build when battles were won or lost in days?

What value did permanent construction have when forward airfields might be abandoned within weeks as military lines shifted? Standing in his Manila headquarters before the final evacuation, Casey wrote in his operational log, “Concrete runways are a peacetime luxury we cannot afford. The perfect has become the enemy of the good, and the good has become the enemy of the possible. ” The entry would prove prophetic, though Casey had no solution to replace the construction methods that were failing so spectacularly.

Meanwhile, 8,000 miles away in Pittsburgh, Carnegie Steel Metallurgist Gerald G. Grulich was reading Aviation Week during his lunch break in the company cafeteria. The magazine’s February issue featured a grim article about runway construction delays hampering American offensive operations. Groich studied the accompanying photographs of abandoned concrete pores and half-finished air strips, then pulled out his everpresent notebook and began sketching. His engineering mind immediately grasped the fundamental problem. Concrete runways were monolithic structures. They either worked perfectly or failed completely.

There was no middle ground, no way to build them incrementally or repair them quickly under combat conditions. But what if runways could be assembled like bridges? What if individual components could be manufactured in American factories, shipped anywhere in the world, then connected together like giant steel puzzle pieces? Groish’s pencil moved across the notebook page, drawing rectangles with carefully spaced circular holes. His colleagues at the neighboring table noticed his sketching and leaned over curiously. “Jerry, uh, what are you designing now?” “Another bridge support?” asked Tom Morrison, a structural engineer who had worked with Grillich on several Pennsylvania railroad projects.

Grillich looked up from his calculations. Airplane runways made from perforated steel sheets that locked together. He showed Morrison the sketch, rows of interlocking panels, each measuring 10 ft x 2 ft, with precisely engineered holes distributed across their surface. Morrison laughed so hard he nearly choked on his sandwich. Jerry, airplanes need solid surfaces, not Swiss cheese. You can’t land a 15-tonon bomber on metal sheets full of holes. The entire cafeteria table joined Morrison’s laughter, but Guilich continued his calculations, unfazed by their skepticism.

That afternoon, alone in Carnegie Steel’s metallurgy laboratory, Groich began the load distribution mathematics that would change warfare forever. His slide rule clicked steadily as he calculated stress patterns across perforated steel surfaces. The conventional wisdom was dead wrong. Holes didn’t weaken steel structures. Properly engineered perforations actually increase strength by redirecting stress loads more efficiently than solid sheets. Every structural engineer understood this principle in bridge design, but no one had applied it to runway construction. By evening, Groich had filled 12 pages with calculations proving that his perforated steel planking could support aircraft weighing up to 20 tons while using 60% less material than solid steel sheets.

Each panel would weigh just 66 lb, light enough for two soldiers to carry, yet strong enough to handle repeated landings by the heaviest American bombers. The mathematics were irrefutable, even if they contradicted everything the aviation industry believed about runway requirements. Gry closed his notebook and stared out at the Pittsburgh skyline, where Carnegie Steel’s blast furnaces painted the winter sky orange. Somewhere in the Pacific, American pilots were dying because they lacked forward airfields. The solution lay in his calculations, waiting for someone with enough authority to trust mathematics over conventional wisdom.

March 15th, 1942, Gerald Groich stood before a blackboard in Carnegie Steel’s main conference room, facing 12 of the company’s senior engineers and three Army procurement officers who had driven up from Washington. His perforated steel runway prototype lay on the conference table. A single 10×2 ft panel weighing exactly 66 lb. Its surface punctured by 384 precisely machined holes arranged in a mathematical pattern that defied conventional engineering wisdom. Gentlemen, load distribution across perforated steel follows the same principles as an I-beam structural design.

Groish began, his chalk moving across the blackboard in steady strokes. These holes don’t weaken the steel, they redirect stress loads more efficiently than solid plates. He drew force vectors radiating through the perforated surface, showing how weight distributed through the whole pattern rather than concentrating at impact points. Each panel can support 75 lbs per square in repeatedly, which means a 15 ton bomber creates a safety margin of nearly 3 to one. Major William Harrison, the lead army procurement officer, studied the prototype skeptically.

He had spent two decades overseeing concrete runway construction projects across the continental United States. And Gurish’s proposal violated every principle Harrison considered fundamental to aviation safety. Mr. Gilich, I appreciate Carnegie Steel’s innovative spirit, but we’re discussing aircraft operations, not bridge construction. Pilots need solid, stable surfaces. This looks like industrial grading. Gurish anticipated the objection. He had spent weeks refining his presentation, knowing that military procurement officers would resist any departure from proven runway specifications. Major Harrison, may I demonstrate the load characteristics?

Without waiting for permission, Groich climbed onto the prototype panel and began jumping up and down. The steel flexed slightly but showed no signs of structural stress. I weigh 170 lb. This panel is supporting my full weight across two square ft of surface area, roughly equivalent to the pressure a B25 bomber wheel exerts during landing. The demonstration failed to impress Harrison. Mr. Gilich, a B-25 weighs 15 tons and lands at 90 mph. Your personal weight test hardly simulates combat landing conditions.

Harrison’s tone carried the authority of someone who had witnessed multiple runway failures during his military career. Furthermore, perforated surfaces would collect debris, create drainage problems, and provide insufficient traction for aircraft tires during wet weather operations. Groich had prepared for these technical objections as well. He flipped to a new page in his engineering notebook, revealing detailed calculations about surface friction coefficients and drainage characteristics. Actually, Major, the perforations improve drainage by allowing water to flow through the surface rather than pooling on top.

As for traction, our laboratory tests show that steel provides superior grip compared to concrete, especially during rain operations. The Army officers exchanged skeptical glances. Captain Douglas Wheeler, Harrison’s technical aid, voiced the concern that dominated military thinking about runway construction. Mr. Groich, even if your mathematics are correct, we’re talking about aircraft safety under combat conditions. One runway failure could kill an entire bomber crew. Why would we risk unproven technology when concrete runways have worked reliably for 20 years?

Grulich sensed the meeting slipping away from him. Military procurement officers were trained to avoid risk, not embrace experimental solutions. But Lieutenant Colonel Casey’s Pacific Theater reports had been circulating through war department channels, and Groich knew that conventional runway construction was failing catastrophically under combat conditions. Captain Wheeler, may I ask how long your current concrete runways require for construction? Wheeler consulted his briefing folder. Standard specifications call for 45 days minimum, assuming optimal conditions and uninterrupted construction schedules. He paused, recognizing where Goritch’s question was leading.

However, combat conditions rarely provide optimal circumstances for concrete curing. Precisely my point, Gilich responded. These perforated steel planking sections can be manufactured in American factories, shipped anywhere in the world, and assembled into operational runways within hours, not months. No concrete mixing, no curing time, no specialized construction equipment. Two soldiers can carry each panel, and the interlocking system requires only basic hand tools for assembly. Major Harrison remained unconvinced. Mr. Gilich, rapid assembly means little if the runway fails during its first combat landing.

Our pilots deserve proven technology, not experimental materials that might collapse under operational stress. Harrison gathered his briefing papers, preparing to end the meeting. I’ll include your proposal in our technical review process, but I suspect the Army Corps of Engineers will require extensive testing before considering any departure from established runway specifications. The meeting concluded with polite handshakes and non-committal promises to study the proposal further. Groich watched the army officers drive away, knowing that his perforated steel planking would disappear into the military bureaucracy unless someone with real authority recognized its potential.

Traditional procurement channels moved too slowly for wartime innovation, especially when that innovation challenged fundamental assumptions about aircraft operations. Two weeks later, Gilich’s breakthrough came from an unexpected source. Captain John Thompson, recently transferred from the 805th Engineer Aviation Battalion to Wright Patterson Field, was reviewing runway construction proposals when Groich’s technical specifications crossed his desk. Unlike the procurement officers who had visited Carnegie Steel, Thompson possessed unique qualifications to evaluate the perforated steel concept. He had flown P40 Warhawks throughout the Philippines campaign, landing on improvised surfaces that military engineers would have considered criminally inadequate.

Thompson studied Groich’s load distribution calculations with professional interest. His combat experience had taught him that aircraft could operate from surfaces far less perfect than military specifications demanded. He had landed damaged fighters on coral beaches, jungle clearings, and bomb cratered concrete strips that bore little resemblance to peacetime runways. The mathematical precision of Guerritch’s design impressed him, but more importantly, the concept addressed real operational problems that Thompson had witnessed firsthand in the Pacific theater. On April 2nd, Thompson drove to Pittsburgh for a personal meeting with Groyich.

The two men spent six hours in Carnegie Steel’s testing facility, examining prototype panels and discussing the practical requirements of combat aviation. Thompson’s questions focused on operational characteristics rather than theoretical specifications. How quickly could damaged panels be replaced? Could the system function with sections missing? Would the interlocking mechanism hold under repeated stress cycles? Gulich answered each question with detailed engineering analysis. But Thompson’s real breakthrough came when he physically tested the prototype runway section. He bounced a 50-lb concrete block against the perforated surface, simulating the impact stress of aircraft landings.

The steel flexed slightly, absorbing the shock, then returned to its original shape without permanent deformation. “Mr. Groich,” Thompson said, running his hands across the perforated surface. “I’ve landed on worse surfaces in combat. This feels more solid than half the improvised strips we used in the Philippines. Thompson’s endorsement carried weight that procurement officers skepticism could not overcome. He possessed credible combat experience, engineering training, and direct responsibility for airfield construction in the European theater. When Thompson submitted his technical evaluation to the War Department, recommending immediate field trials of Guich’s perforated steel planking system, military aviation officials finally had an authoritative voice supporting the innovative runway concept.

By May 15th, the Army authorized construction of a prototype runway at Wright Patterson Field. Guich’s mathematical theory would finally face the ultimate test, supporting actual aircraft under operational conditions. The success or failure of those initial landings would determine whether one civilian engineers calculations could revolutionize military aviation or whether conventional wisdom about solid runway surfaces would prove unshakable even under wartime pressure. June 23rd, 1942, Wright Patterson Field, Ohio. Captain John Thompson stood at the edge of a 30,000 ft runway that existed nowhere in military engineering manuals.

1500 perforated steel panels stretched across the Ohio grassland. Each section locked to its neighbors through Groik’s interlocking hook system. The assembled surface looked like an enormous steel checkerboard, its thousands of precisely machined holes catching the morning sunlight. Thompson checked his watch. 0830 hours. In 30 minutes, test pilot Lieutenant Robert Mitchell would attempt the first official landing of a military aircraft on perforated steel planking. The stakes extended far beyond a single test flight. Colonel James Divine, chief runway engineer for the Army Corps, had arrived from Washington with specific orders to evaluate whether Groich’s system could replace concrete construction in forward combat zones.

Divine carried decades of successful runway projects on his record. From Kellyfield in Texas to Hickhamfield in Hawaii, everyone had been built with concrete, steel reinforcement, and construction timelines measured in months. The idea of landing heavy bombers on interlocking metal sheets struck him as fundamentally unsound, regardless of Goritch’s mathematical proofs. Captain Thompson, Divine said, examining the perforated surface through his field glasses. I’ve seen experimental runway materials fail catastrophically during testing. If this system collapses under a 3,000lb trainer aircraft, imagine the consequences when we’re discussing 15-tonon bombers under combat conditions.

Divine’s concern reflected genuine responsibility for pilot safety rather than bureaucratic obstruction. He had investigated too many runway failures that resulted in aircraft casualties to approach unproven technology casually. Thompson understood Divine’s reservations, but his combat experience provided a different perspective on acceptable risk. Colonel, I’ve landed damaged fighters on surfaces that would horrify peaceime safety inspectors. The question isn’t whether this system meets peaceime standards. It’s whether perforated steel provides better operational capability than the concrete runways we can’t build fast enough under combat conditions.

Thompson gestured toward the assembled panels. These 1500 sections were installed by 12 men in 8 hours. A concrete runway of equivalent length would require 300 workers and 6 weeks minimum. At 0900 hours precisely, Lieutenant Mitchell’s North American AT6 Texan trainer appeared on final approach. The single engine aircraft weighed 3,000 lb fully loaded and represented the lightest operational military plane in the Army inventory. If perforated steel planking could not support an AT6, it certainly could not handle the B-25 bombers and P47 fighters that would define the systems ultimate utility.

Mitchell maintained standard landing procedures, touching down at 65 mph with his landing gear absorbing the initial impact. The moment his wheels contacted Groich’s perforated surface, Thompson heard a distinctive metallic ringing, not the sharp crack of structural failure, but the resonant ping of steel flexing under load and returning to its original shape. The aircraft rolled normally for 800 ft before Mitchell applied brakes and brought the AT6 to a controlled stop. Surface feels solid as concrete, Mitchell reported over his radio to the control tower.

No unusual vibrations, no indication of structural movement. The perforations create interesting visual effects during roll out, but aircraft handling characteristics remain completely normal. Mitchell taxied the trainer aircraft to the runways end, then executed a standard takeoff using the same perforated surface. Again, the system performed flawlessly with no sign of panel separation or surface deterioration. Divine remained cautious despite the successful test. Captain Thompson, an AT6 trainer hardly represents the operational loads we’ll encounter in combat theaters. I need to see this system handle aircraft that actually matter for strategic operations.

Divine skepticism was professionally warranted. Military procurement decisions affected thousands of pilots and rushing unproven technology into combat deployment could result in catastrophic failures when American lives depended on runway reliability. Thompson anticipated this objection. Colonel, I’ve arranged for escalating load tests over the next two weeks. Tomorrow, we’ll test a B25 Mitchell bomber, 15 tons gross weight, 90 mph landing speed. If that succeeds, we’ll progress to fully loaded transport aircraft and eventually to the heaviest bombers in our inventory.

Thompson’s testing protocol reflected systematic engineering validation rather than reckless experimentation. The B-25 test occurred on June 25th under perfect weather conditions. Mitchell’s bomber approached the perforated runway at standard operational speed. Its twin right R260 cyclone engines throttled back for landing configuration. Thompson watched through binoculars as the 15-tonon aircraft contacted Groich’s steel surface with significantly greater impact force than the previous trainer test. The perforated panels flexed visibly under the bomber’s main landing gear, distributing the concentrated wheel loads across multiple interlocking sections exactly as Groich’s calculations had predicted.

Runway performance excellent, Mitchell reported after completing his landing roll and taxi procedures. Surface provides adequate traction, no structural movement detected, aircraft handling normal throughout all phases of ground operations. The test pilot’s professional assessment carried enormous weight with military evaluators who relied on operational air crew reports to judge new equipment under realistic conditions. Divine’s resistance began wavering as the test results accumulated. His engineering training told him that Groich’s mathematical analysis was fundamentally sound, even though it contradicted established runway construction practices.

More importantly, reports from the Pacific Theater continued emphasizing the desperate need for rapid airfield construction capability. Lieutenant Colonel Casey’s urgent requests for alternative runway systems were reaching the highest levels of Army command, creating pressure for innovative solutions, regardless of their departure from traditional specifications. By July 15th, the Wright Patterson trials had validated perforated steel planking for aircraft weighing up to 20 tons. Test pilots reported consistently positive experiences across multiple aircraft types from single engine fighters to twin engine medium bombers.

The interlocking panel system showed no signs of structural fatigue despite repeated heavy aircraft operations and the installation process proved remarkably efficient compared to concrete construction timelines. The breakthrough moment came when Divine submitted his official technical evaluation to the War Department. Perforated steel planking performs in accordance with manufacturer specifications and provides acceptable operational characteristics for military aircraft operations, his report concluded. Recommend immediate procurement of sufficient materials for field trials in active combat theaters. The man who had initially dismissed Goritch’s system as impractical now championed its adoption based on objective engineering evidence.

Carnegie Steel received orders for 50,000 perforated panels by August 1st, with production specifications calling for 2,000 sections per day once manufacturing reached full capacity. Each panel required precise perforation, 384 holes machined to exact dimensional tolerances, followed by galvanizing treatment to prevent corrosion under tropical conditions. Quality control became critical since a single defective panel could compromise an entire runway section under combat stress. Gorich supervised the production scaling personally, working 18-hour days to ensure that manufacturing processes maintained the mathematical precision his design required.

The transition from laboratory prototype to mass production revealed numerous technical challenges from rivet strength specifications to surface coating procedures. But by September, Carnegie Steel’s Pittsburgh facility was producing perforated steel planking at rates that could support major military operations worldwide. The impossible idea sketched on a lunch napkin was becoming the foundation of American air power projection across global combat theaters. October 8th, 1942. Casablanca, French Morocco. Captain John Thompson stood kneedeep in uh Atlantic Surf watching Liberty ships discharge the first combat shipment of perforated steel planking onto North African beaches.

Operation Torch had commenced 72 hours earlier and American forces needed operational airfields immediately to support ground troops advancing inland against Vichi French resistance. Traditional concrete runway construction would require 6 weeks minimum, time that General Patton’s armored columns could not afford while facing German reinforcements arriving daily from Tunisia. Thompson’s engineering battalion had practiced PSP assembly procedures for 2 months at Fort Belvoir, but theory differed dramatically from reality when German Stookas were bombing supply convoys and French artillery was targeting beach landing zones.

Each 10×2 ft panel weighed 66 lb when dry, but Atlantic spray and Moroccan sand added another 10 lb of dead weight that exhausted soldiers had to manhandle from ship to shore through heavy surf. The interlocking hooks that functioned perfectly in Ohio testing laboratories now jammed with salt corrosion and gritty debris that required constant cleaning to maintain proper panel connections. Sir, we’ve got 800 panels ashore and ready for assembly. Sergeant William Morrison reported, gesturing toward neat stacks of perforated steel arranged in precise geometric patterns across the Casablanca beach head.

Engineering calculations show we need 1500 sections for a 3000 ft operational runway capable of handling P40 Warhawk operations. Morrison consulted his field manual, cross-referencing PSP specifications against projected aircraft loads. At current unloading rates, we’ll have sufficient materials by 18800 hours today. Thompson checked his tactical situation map, noting German reconnaissance flights that had been circling American positions since dawn. Intelligence reports indicated that Luftwafa bombers based in Rabat were preparing strikes against Allied beach head operations, which meant American air cover was critically necessary within 24 hours.

Sergeant Morrison, begin PSP assembly immediately with available materials. We’ll extend the runway as additional panels come ashore, but I need a minimum 1500 ft strip operational by dawn tomorrow. The assembly process revealed both the systems revolutionary capabilities and its practical limitations under combat conditions. Groich’s interlocking design allowed rapid installation. Two soldiers could position and connect each panel in approximately 3 minutes using basic hand tools. However, North African sand created unexpected challenges that laboratory testing had not anticipated.

Windblown particles infiltrated the panel connections, requiring constant maintenance to prevent separation during aircraft operations. More critically, the desert environment caused thermal expansion that loosened interlocking hooks unless installation crews maintained precise spacing tolerances. By 1800 hours, Thompson’s battalion had assembled a 2,000 ft PSP runway despite intermittent stooka attacks that interrupted construction multiple times. The perforated surface looked alien against the Moroccan landscape, a geometric steel carpet stretching across sand dunes and scrub vegetation. Local Arab observers watched the installation with fascination, having never seen aircraft operations conducted from anything other than packed earth or concrete surfaces.

The operational test came at 06:30 the following morning when Major Robert Johnson approached the PSP strip in his Republic P47 Thunderbolt. The 7-tonon fighter represented a significant load increase over previous testing, and Johnson’s combat mission profile required maximum fuel and ammunition loads that pushed aircraft weight to operational limits. Thompson monitored the landing attempt through field glasses, knowing that success or failure would determine whether PSP technology could support actual combat operations rather than merely peacetime testing procedures. Johnson’s Thunderbolt contacted the perforated surface at 85 mph with characteristic P47 authority.

The steel panels flexed visibly under the fighter’s main landing gear, creating distinctive metallic sounds that Thompson had learned to interpret during Ohio trials. No panel separation occurred. No structural failure developed, and Johnson’s aircraft rolled normally to a controlled stop within 800 ft. Runway surface acceptable for operational use, Johnson reported via radio. Aircraft handling characteristics normal. No unusual vibrations or control problems detected. The Casablanca PSP strip became operational on October 10th, supporting 12 P47 sorties against German positions near Rabot.

Each landing and takeoff validated Groich’s mathematical predictions about load distribution and structural integrity. More importantly, the rapid installation timeline had provided air cover for American ground forces exactly when needed rather than 6 weeks later when concrete runways would have become available. Word of the North African success reached General Henry Arnold, commanding general of Army Air Forces within 48 hours. Arnold’s strategic vision for global air power projection depended entirely on rapid airfield construction capability since American bombers and fighters could only operate from bases within range of strategic targets.

The PSP system promised to revolutionize this fundamental limitation by allowing airfield construction anywhere American forces could establish temporary control from Pacific coral at holes to European farmland. Arnold authorized massive PSP production increases with orders for 500,000 panels to support upcoming Mediterranean and Pacific operations. Carnegie Steel’s Pittsburgh facility expanded to 24-hour production schedules, employing 3,000 workers dedicated exclusively to perforated steel planking manufacturer. Quality control became increasingly challenging as production volume increased, but Guilich’s design specifications proved robust enough to maintain structural integrity, even with minor manufacturing variations.

December 15th brought the ultimate validation when Admiral Chester Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet began incorporating PSP airfields into Operation Cartwheel, the systematic advance toward Japanese strongholds in the Solomon Islands. Guadal Canal’s Henderson Field received PSP extensions that doubled its operational capacity within 72 hours, transforming a marginal fighter base into a major bomber staging area. The installation required no concrete, no specialized construction equipment, and no extended curing periods that Japanese artillery could target during vulnerable construction phases. By year’s end, 47 PSP airfields were operational across three combat theaters from North Africa to the Southwest Pacific.

Total runway length exceeded 150 mi of perforated steel surface, supporting everything from single engine fighters to 4ine heavy bombers. The mathematical precision that Groich had calculated on Carnegie steel napkins was proving itself under the most demanding operational conditions imaginable. But the ultimate test still lay ahead. Intelligence reports from the Pacific indicated that Japanese forces were developing new artillery tactics specifically designed to target American airfield construction. The static nature of concrete runways made them vulnerable to systematic bombardment that could render them inoperational for weeks.

PSP’s modular design offered theoretical advantages for rapid repair, but those advantages had never been tested under concentrated enemy fire. The Anio Beach Head would provide that test under conditions where failure meant not just engineering disappointment, but potential military disaster for thousands of Allied soldiers depending on air support for their survival. January 22nd, 1944. Anzio Beachhead, Italy. Captain John Thompson crouched in a muddy crater 50 yards from the PSP airirstrip that had become the lifeline for 36,000 Allied soldiers trapped on the narrow coastal plane.

German 88 mm artillery shells had been falling steadily for 18 hours. Part of a systematic bombardment designed to destroy the perforated steel runway that allowed American P47 Thunderbolts to provide close air support for the besieged beach head. At 0315 hours, a direct hit had obliterated a 200 ft section of the runway’s center, leaving a jagged gap that conventional wisdom declared impossible to repair under combat conditions. Thompson studied the damage through his field glasses as another artillery barrage erupted across the airfield perimeter.

27 PSP panels lay twisted and shattered, their interlocking hooks severed by the concussion wave that had created a crater 15 ft deep and 30 ft across. Standard runway repair doctrine called for heavy construction equipment, concrete patches, and minimum 48-hour curing periods. Resources that simply did not exist on a contested beach head where German forces controlled the surrounding high ground and could observe every Allied movement. Sir, we’ve got P-47s inbound at 0600 with close support missions for the British First Division, Sergeant Morrison reported, his voice barely audible over the continuing artillery fire.

Without air cover, General Lucas expects German counterattacks to overrun our forward positions by nightfall. Morrison’s situation assessment reflected the brutal mathematics of beach head warfare. Allied ground forces could hold their defensive perimeter only as long as American aircraft could suppress German artillery and armor concentrations. Thompson had trained his engineering crews for exactly this scenario during PSP installation exercises at Fort Belvoir, but theory differed dramatically from reality when Nevilleer rocket salvos were targeting repair operations and Messmid fighters were strafing supply convoys attempting to deliver replacement panels.

The modular nature of Groish’s design theoretically allowed rapid section replacement, but only if engineering crews could work without constant interruption from enemy fire. Sergeant Morrison organized 12man repair teams with replacement panels staged at the crater perimeter, Thompson ordered, consulting his tactical watch in the pre-dawn darkness. German artillery observers can see our airfield clearly from Monty Battalia, so we’ll conduct repair operations during the brief intervals between bombardment cycles. Thompson’s approach reflected hard-learned lessons about working under direct observation.

Successful repair required precise timing coordinated with German firing patterns rather than continuous construction efforts. At 0400 hours, Thompson’s first repair team sprinted across the exposed runway surface, carrying replacement PSP panels toward the bomb crater. German artillery had maintained regular firing schedules throughout the night with approximately 12minute intervals between major bombardment cycles. This narrow window provided barely enough time to position and connect four panels before the next salvo forced crews to abandon the repair site and seek protective cover.

The interlocking hook system that had functioned flawlessly during peacetime testing now proved its combat value under the most extreme operational conditions. Each PSP panel weighed 66 lb, light enough for two soldiers to manhandle quickly across broken terrain, yet strong enough to support repeated aircraft landings once properly connected to adjacent sections. More critically, damaged panels could be disconnected and replaced individually without affecting surrounding runway sections, a capability that concrete runways could never provide. Thompson’s crews worked with mechanical precision despite the chaos surrounding them.

As German shells impacted 50 yards away, sending shrapnel whistling overhead, soldiers methodically positioned replacement panels into the crater gap, aligned interlocking hooks, and secured connections using standard field tools. The perforated surface that had once seemed alien during North African testing now felt familiar and reliable under Italian combat conditions. By 0530 hours, the repair teams had installed 18 replacement panels, reducing the runway gap from 200 ft to approximately 60 ft. Thompson calculated that P47 operations could resume with this reduced opening since Thunderbolt pilots could easily clear a 60 ft gap during takeoff and landing procedures.

However, complete runway restoration required nine additional panels to restore full operational capability for heavier aircraft like B-25 Mitchell bombers. The critical moment came at 0545 when German artillery observers detected the ongoing repair activity and redirected their fire directly onto the PSP runway. Thompson watched helplessly as 88 mm shells exploded across the partially repaired surface, sending steel fragments and concrete debris in all directions. Conventional runway materials would have been destroyed completely by this concentrated bombardment, requiring weeks of reconstruction using heavy equipment that did not exist on the Anzio beach head.

Instead, Groich’s modular design absorbed the punishment with remarkable resilience. Individual panels that received direct hits were destroyed completely, but surrounding sections remained undamaged and fully functional. The interlocking system distributed shock loads across multiple panels, preventing cascade failures that would have rendered entire runway sections unusable. More importantly, damaged panels could be disconnected immediately and replaced with spare sections that Thompson’s supply teams had prepositioned around the airfield perimeter. At 0600 hours precisely, Lieutenant Robert Johnson’s P47 Thunderbolt appeared on final approach despite the continuing German artillery fire.

Johnson had been briefed about the incomplete runway repairs, but his close support mission was critically necessary for Allied ground forces facing renewed German attacks across the beach head perimeter. Thompson held his breath as the 7-tonon fighter contacted the patched PSP surface at standard landing speed. Runway surface acceptable, Johnson reported via radio after completing a perfect landing and taxi to his revetment area. panel connection solid, no unusual vibrations detected during roll out. Within 15 minutes, Johnson had refueled, rearmed, and taken off again using the same repaired runway section, demonstrating that PSP could provide continuous combat operations, even under direct enemy fire.

The Anio validation established PSP as an indispensable component of Allied air power projection. By February 1st, Thompson’s engineering battalion had repaired the runway seven times following German bombardments, each time restoring full operational capability within 4 hours using replacement panels delivered by LST landing ships. The cumulative damage would have rendered any concrete runway permanently unusable, but Gilich’s modular design allowed indefinite repair cycles limited only by spare panel availability. General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army headquarters received detailed reports about PSP performance under combat conditions with particular emphasis on rapid repair capabilities that maintained air support during critical ground operations.

Clark’s strategic assessment concluded that perforated steel planking had fundamentally altered the relationship between air power and ground operations by eliminating the vulnerability of fixed runway installations to enemy artillery fire. Word of the Anzio success reached the highest levels of Allied command within days. General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander for Operation Overlord, studied PSP specifications with intense interest as his staff planned airfield requirements for the upcoming Normandy invasion. Eisenhower’s strategic vision required immediate air support for amphibious operations, which meant operational runways within 24 hours of initial landings rather than the weeks needed for concrete construction.

The mathematical precision that Gerald Groich had calculated in a Pittsburgh cafeteria was proving decisive not just in engineering terms, but in strategic military outcomes that affected the entire course of World War II. One civilian engineer’s willingness to challenge conventional wisdom about runway construction had created a capability that was reshaping how modern warfare integrated air power with ground operations across global combat theaters.