December 27th, 1942. Port Moresby, New Guinea. The lightning strikes. The morning sun cast long shadows across the steel matting of Loki airfield as ground crews pulled camouflage netting from twin boommed silhouettes. 12 Lockheed P38F Lightnings of the 39th Fighter Squadron, 35th Fighter Group, sat fueled and armed, their distinctive twin tails gleaming in the tropical dawn. Intelligence report from Coast Watchers. Major Japanese air raid developing. Multiple formations approaching Buuna. Estimated 40 aircraft. Fighter escort confirmed. Time to intercept, 30 minutes.

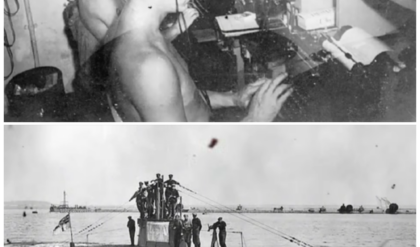

Captain Thomas Lynch checked his instruments and signaled his flight. Among his pilots was Second Lieutenant Richard Bong, temporarily attached from the 49th Fighter Group’s 9inth Squadron, still waiting for their own P38s to arrive. What none of them knew was that this morning would mark the beginning of a fundamental shift in Pacific Air combat. The Japanese pilots approaching Buuna had encountered P38s only briefly in previous weeks. Their intelligence reports remained uncertain about the strange twin boomed fighter capabilities.

Within hours, that uncertainty would transform into shocked recognition. The Imperial Japanese Navy’s elite fighter pilots had dominated Pacific skies for 13 months. The Mitsubishi A6M0’s legendary maneuverability had become the nightmare of Allied pilots. Turn radius of 950 ft. Climb rate to 6,000 ft in 7 minutes 27 seconds. Maximum speed of 331 m hour. These statistics had translated into overwhelming victory in China and the early Pacific campaigns. American pilots in their Bell P39 era Cobras and Curtis P40 Warhawks had learned through blood and loss that engaging a zero in a turning fight meant almost certain death.

But the P38 Lightning represented a revolutionary philosophy of air combat. Twin Allison V1 1710 engines each producing 1,150 horsepower. Turbo superchargers maintaining power at altitudes where other fighters struggled for breath. Maximum speed of 414 mph. Service ceiling of 44,000 ft. And concentrated in the nose, a devastating armament package. One 20 mm Hispano cannon and 450 caliber Browning machine guns. All firing straight ahead without the convergence problems of wing-mounted weapons. Lieutenant Richard Bong had studied these specifications during his training at Hamilton Field, California.

A farm boy from Popular, Wisconsin, who’d learned to fly in the civilian pilot training program, Bong understood that the Lightning’s advantage lay not in turning with zeros, but in avoiding the turning fight altogether. Speed, altitude, firepower. Strike from above, dive through the enemy formation, climb back to altitude. These tactics demanded discipline, patience, and complete rejection of traditional dog fighting instincts. Aboard the approaching Japanese formation, veteran pilots from the laybased air groupoups flew their standard escort patterns. The mixed force of Mitsubishi A6 M0, Nakajima Key 43 Oscars, and Iiched 3A Val dive bombers represented the cream of Japanese naval aviation.

These pilots had swept across the Pacific from Pearl Harbor to the Dutch East Indies, rarely meeting serious opposition. American fighters typically struggled above 15,000 ft, and their inferior climb rates made them predictable targets. The morning’s mission appeared routine. Escort the dive bombers to Buna, suppress any Allied fighter opposition, return to base. Japanese pilots had noticed the occasional twin boomed aircraft in recent weeks, but hadn’t yet grasped their significance. Some thought they were reconnaissance planes or light bombers.

The possibility that Americans had developed a fighter specifically designed to negate the Zero’s advantages hadn’t occurred to Japanese tacticians, but at 18,000 ft, the P38 formation held every advantage. Captain Lynch led the attack, pushing his lightning into a dive that quickly exceeded 400 mph. Behind him, Bong and the other pilots selected their targets. The concentrated firepower from the nosemounted weapons allowed them to open fire at ranges exceeding 400 yd, well beyond the effective range of the Zer’s light armament.

Lynch’s guns destroyed an Oscar in the opening pass. The Japanese fighter simply disintegrated under the impact of 20 mm cannon shells and50 caliber bullets. As Lynch climbed back to altitude, zero pilots attempted to follow, but found their aircraft shuddering violently as they approached 400 mph in the dive. Warning bells sounded in their cockpits as they neared their structural limits. Lieutenant Bong spotted a Zero attempting to engage Lynch and rolled into a deflection shot. His first combat burst found its mark, sending the Zero spinning earth in flames.

As he pulled up, three more zeros converged on his position. Bong pushed his throttles forward and dove away, accelerating to over 450 mph. The Japanese pilots could only watch as the strange twin boommed fighter disappeared into the distance, completely untouchable. Pulling out of his dive just above the jungle canopy, Bong spotted a Val dive bomber recovering from its attack run. A short burst from 100 yards sent it crashing into the jungle in a ball of flame. These were Bong’s first two confirmed victories, the beginning of what would become the highest scoring American ace career of the war.

The engagement lasted less than 10 minutes. The 39th Squadron claimed 12 Japanese aircraft destroyed, including victories by Lynch, Bong, and second left tenant Carl Plank. No P38s were lost. Japanese afteraction reports expressed confusion and alarm. Pilots described aircraft possessing impossible speed and climbing ability, engaging from beyond normal combat range. The comfortable world of horizontal maneuvering combat where Japanese pilots excelled had suddenly become a vertical battlefield where speed and altitude determined survival. This transformation sent shock waves through Japanese naval aviation headquarters at Rabol.

Intelligence officers scrambled to reassess the P38’s capabilities. The aircraft’s twin engine configuration had led them to categorize it as a heavy fighter unsuitable for air-to-air combat. They hadn’t anticipated that American engineers had created something entirely new, a fighter that achieved superiority through vertical maneuvering rather than horizontal agility. The technical revolution represented by the P38 became increasingly clear through subsequent encounters. The Lightning’s turbo superchargers allowed it to maintain full power at altitudes where normally aspirated engines lost 50% of their output.

Its diving speed approached the sound barrier faster than any Japanese aircraft could follow without structural failure. Its ability to convert speed to altitude meant P38 pilots could regain their perch above enemy formations within seconds of an attack. On January 7th, 1943, the reality of this new threat became undeniable. Nine P38s escorting bombers overlay encountered approximately 20 Japanese fighters. Traditional tactical doctrine suggested the outnumbered Americans should adopt defensive positions. Instead, the P38s climbed to 25,000 ft and initiated diving attacks from positions the Japanese couldn’t reach.

Lieutenant Richard Bong, now flying regularly with the 39th Squadron while awaiting his unit’s P38s, demonstrated the Lightning’s lethal efficiency. Diving from altitude, he destroyed a key 43 Oscar with a deflection shot at 300 yd. As Japanese fighters attempted to climb toward him, Bong executed a chandel that carried him back to 20,000 ft, completely outside their engagement envelope. From this perch, he selected another target and repeated the process. The geometry of vertical combat was something Japanese pilots had never encountered.

While a Zero could outturn any American fighter, it couldn’t match the P38’s speed in a dive without catastrophic structural failure. It couldn’t follow the Lightning’s zoom climb without stalling. It couldn’t catch a P38 that chose to disengage using superior speed. The horizontal battlefield where Japanese pilots reigned supreme had been replaced by a three-dimensional arena where altitude and velocity trumped turning radius. Veteran Japanese pilots struggled to adapt. Their entire training emphasized close-range maneuver in combat, getting on an opponent’s tail through superior turning ability.

Against the P38, these tactics were useless. By the time a zero pilot maneuvered into firing position, the lightning was already a mile away and climbing through altitude bands the Japanese fighter couldn’t reach. The psychological impact proved as devastating as the tactical disadvantage. Japanese pilots who had enjoyed qualitative superiority since the war’s beginning found themselves helpless against an enemy that refused to fight on their terms. The stress of constantly scanning above, knowing death could plummet from altitudes they couldn’t reach, eroded morale.

Some pilots developed combat fatigue symptoms previously unknown in Japanese military culture. By February 1943, the P38 presence in the Southwest Pacific was expanding rapidly. The 9inth Fighter Squadron of the 49th Fighter Group finally received their lightnings. The 80th fighter squadron of the eighth fighter group began transitioning from P39s to P38s. The 475th Fighter Group, an all lightning unit, was forming in Australia. Each new squadron that arrived had studied the combat reports of pilots like Lynch and Bong, refining tactics that maximized the P38’s advantages.

The training programs instituted by squadron commanders emphasized altitude discipline above all else. Altitude is life insurance became the mantra. Speed is life. Pilots learned to resist the instinct to turn with enemy fighters instead maintaining high velocity and using vertical maneuvers. The high-speed yo-yo allowed a P38 to convert excess speed into altitude while reversing direction. The barrel roll attack used the Lightning’s roll rate to maintain guns on target while preserving momentum. Japanese attempts to counter these tactics proved largely ineffective.

The Kawasaki K61 Tony with its liquid cooled engine and heavier armament was designed specifically to engage high alitude American bombers. But even the Tony couldn’t match the P38’s performance above 20,000 ft. The Nakajima Key 44 Shoki emphasized speed and climb rate over maneuverability, but still fell short of the Lightning’s capabilities. Intelligence reports from Japanese units revealed growing desperation. Pilots were instructed to avoid combat with P38s unless possessing overwhelming numerical superiority and advantageous position. Even then, engagement was discouraged above 15,000 ft, where the Lightning’s performance advantage became insurmountable.

Some units attempted to lure P38s into lowaltitude turning fights, but American pilots had learned to maintain discipline and refuse engagement on unfavorable terms. The industrial dynamics compounded Japan’s tactical disadvantage. Loheed’s production line in Burbank, California was achieving remarkable efficiency. By March 1943, the factory was producing 10 P38s per day. Each aircraft required approximately 37,000 man-h hours to construct, but American industrial capacity made this investment sustainable. Japanese aircraft production, constrained by material shortages and bombing damage, struggled to replace combat losses.

Training disparities widened the gap further. American P38 pilots arrived in theater with 300 or more flight hours, including 50 hours in type. They had practiced vertical tactics, gunnery, and formation flying extensively. Japanese replacement pilots rushed through abbreviated training programs, averaged less than 100 total flight hours. Many had never flown above 20,000 ft before encountering P38s in combat. The Battle of the Bismar Sea in March 1943 demonstrated the P38 strategic impact. Lightnings flew top cover for Allied bombers attacking a major Japanese convoy.

When zero escorts rose to intercept, the P38s executed perfect vertical tactics, destroying multiple Japanese fighters while preventing any effective defense of the convoy. Eight transport ships and four destroyers were sunk, dealing a crushing blow to Japanese reinforcement efforts. Among the P38 pilots establishing dominance over the Solomons, several names became legendary. Captain Thomas Lynch of the 39th Fighter Squadron refined vertical tactics to an art form, eventually scoring 20 confirmed victories before his death in March 1944. Lieutenant Richard Bong continued his remarkable scoring streak, demonstrating an uncanny ability to position his P38 for perfect deflection shots.

In August 1943, a new name entered the Lightning Ace roster. Lieutenant Thomas Maguire, assigned to the newly formed 475th Fighter Group’s 431st Fighter Squadron, scored his first victories on August 18th over Wiiwak. Flying top cover for bombers, Maguire’s flight encountered approximately 20 Japanese fighters. In his first combat engagement, Maguire shot down two Kai 43 Oscars and one Kai 61 Tony, becoming an ace in just two days after adding two more victories on August 21st. Maguire’s combat philosophy emphasized aggressive vertical tactics and precise gunnery.

He would eventually write a manual titled Combat Tactics in the Southwest Pacific Area that became required reading throughout the Fifth Air Force. His techniques included the Maguire roll, a high-speed barrel roll that maintained offensive position while preserving momentum, and the vertical reverse, using the P38’s climb capability to reverse positions with a pursuing enemy. The strategic implications of P38 dominance extended beyond individual combat. The Lightning’s range, exceeding 1,000 mi with drop tanks, allowed American planners to strike Japanese bases previously considered secure.

Fighter sweeps could reach Rabol from New Guinea, achieving air superiority before bombers arrived. The ability to escort bombers throughout their entire mission profile eliminated the vulnerability windows that Japanese interceptors had previously exploited. On April 18th, 1943, the P38’s unique capabilities enabled one of the war’s most significant missions. American codereakers had intercepted Admiral Isuroku Yamamoto’s travel itinerary for an inspection tour of Solomon Islands bases. The mission to intercept him would require a 435m overwater flight from Guadal Canal, precise navigation without landmarks, and exact timing to arrive at the intercept point when Yamamoto’s aircraft passed through.

Only the P38 possessed the range, speed, and navigation equipment for such a mission. Major John Mitchell of the 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, led 16 Lightnings on the longest fighter intercept mission of the war. Flying at wavetop height to avoid radar detection, maintaining radio silence throughout, the P38s navigated by dead reckoning for over 2 hours. Mitchell’s navigation proved perfect. At 0934, exactly as planned, Yamamoto’s two Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers appeared with their 6 escorts. Captain Thomas Lania Jr.

and Lieutenant Rex Barber rolled into their attack as the top cover engaged the escorts. Barber’s concentrated fire sent the Admiral’s bomber crashing into the jungle, killing Japan’s most brilliant naval strategist and dealing a devastating blow to Japanese morale. The psychological impact rippled through Japanese military leadership. If American fighters could reach out across hundreds of miles of ocean with such precision, no one was safe. The myth of Japanese invincibility already damaged by Midway and Guadal Canal suffered another crushing blow.

The P38 had demonstrated not just tactical superiority, but strategic reach that Japanese planners hadn’t anticipated. Following Yamamoto’s death, Japanese fighter tactics underwent desperate revision. Pilots were instructed to attack P38s only when possessing altitude advantage, numerical superiority of at least 3:1, and surprise. Even then, engagement was to be brief with immediate disengagement if the initial attack failed. These defensive tactics represented complete reversal from the aggressive spirit that had characterized Japanese fighter doctrine. The introduction of new Japanese aircraft failed to restore balance.

The Kawasaki Ki 84 Frank appearing in late 1943 could match the P38 speed at medium altitudes, but still couldn’t compete above 25,000 ft. The Mitsubishi J2M Ryden emphasized climb rate and high altitude performance, but sacrificed range and maneuverability. Neither aircraft appeared in sufficient numbers to challenge American air superiority. By November 1943, the transformation was complete. Japanese daylight operations over the Solomons had virtually ceased. Naval vessels moved only under cover of darkness. Supply runs to forward bases were conducted by submarines and fast destroyers in nighttime dashes.

The proud Japanese naval air force that had swept across the Pacific in 1941 to42 had been reduced to fertive defensive operations. The statistics told a stark story. In the years since significant P38 operations began, Japanese fighter units in the Solomons and New Guinea had suffered catastrophic losses. The 251st Air Group, which began 1943 with 80 pilots, had only 10 original members surviving by year’s end. The 204th Air Group lost 70% of its pilots in 6 months. The 582nd Air Group was withdrawn from combat entirely after losing 80% of its aircraft in 4 months of operations against P38 equipped American units.

American losses, while not insignificant, were sustainable. P38 squadrons typically achieved kill ratios of 5:1 or better. More importantly, American pilots who survived being shot down were often rescued by air sea rescue services and returned to combat. Japanese pilots who went down over water usually drowned. American aircraft damaged in combat were repaired and returned to service. Japanese aircraft with similar damage were often abandoned due to lack of spare parts. The industrial disparity continued widening. By December 1943, Loheed had delivered over 2,000 P38s to combat theaters.

Monthly production exceeded 400 aircraft. Japanese production of all fighter types barely reached 500 per month, and many of these were retained in the home islands for defense. The arithmetic of attrition warfare had become inexurable. Training standards diverged even further. American P38 pilots arriving in late 1943 had extensive training in vertical tactics, instrument flying, and long range navigation. Many had practiced combat maneuvers against captured Japanese aircraft, understanding exactly their opponents capabilities and limitations. Japanese replacement pilots rushed through programs shortened from 2 years to 6 months arrived with minimal combat preparation and no experience against P38s.

The human dimension of this transformation cannot be overlooked. Japanese pilots who had entered the war as elite warriors confident in their superiority found themselves helpless against an enemy they couldn’t reach or catch. Letters home captured after island battles revealed deep demoralization. Some pilots wrote of nightmares about twin boomed shadows diving from the sun. Others requested transfers to ground units rather than face P38s again. American pilots conversely flew with growing confidence. The P38 gave them every advantage. Speed, altitude, firepower, and range.

They could choose when and how to engage, always maintaining the initiative. This psychological edge proved as valuable as the technological superiority. Confident pilots flew more aggressively, took calculated risks, and achieved better results. Richard Bong exemplified this confidence. By April 1944, he had surpassed Eddie Rickenbacher’s World War I record of 26 victories. His combat technique had evolved to near perfection. Bong would climb to 30,000 ft beyond the reach of any Japanese fighter, then select his targets carefully. His attacks were swift, precise, and lethal.

He averaged less than 100 rounds fired per victory, demonstrating remarkable gunnery skill. Bong’s eventual total of 40 confirmed victories, all scored in P38s, represented not just personal skill, but systematic superiority. His victims included veteran Japanese aces who simply couldn’t counter the Lightning’s performance advantages. In one engagement over Helandia, Bong shot down three Japanese fighters in less than 5 minutes using perfect vertical tactics that left his opponents unable to respond. Thomas Maguire pushed the P38’s capabilities even further.

His manual on combat tactics became doctrine throughout the Pacific theater. Maguire emphasized the importance of mutual support with P38 elements working in coordinated vertical scissors that trapped Japanese fighters between multiple attacking lightnings. His eventual 38 victories scored between August 1943 and January 1945 demonstrated the lethal efficiency of properly executed tactics. The technological evolution of the P38 continued throughout the campaign. The G model introduced improved turbo superchargers that maintained power above 30,000 ft. The H model featured upgraded engines producing 1,425 horsepower each.

The J model relocated intercoolers to the engine booms, improving pilot visibility and high altitude performance. The L model added hydraulically boosted ailerons that dramatically improved roll rate. Each improvement shifted the combat equation further in America’s favor. The P38J could operate effectively at 35,000 ft. Altitudes where Japanese pilots required oxygen masks just to remain conscious. The L model’s improved roll rate eliminated the Zero’s last marginal advantage in horizontal maneuvering. By late 1944, there was literally nothing a Japanese fighter could do better than a P-38L.

Japanese responses became increasingly desperate. Ramming attacks, considered honorable, if wasteful, increased as conventional tactics failed. Special attack units prepared for one-way missions. Some pilots attempted to lure P38s into clouds where visual confusion might negate the lightning’s advantages. These expedience achieved occasional success, but couldn’t alter the fundamental imbalance. The Philippines campaign of late 1944 demonstrated the P38’s matured capabilities. Lightning squadrons achieved air superiority over Lee within days of the invasion. Japanese attempts to reinforce by air resulted in catastrophic losses.

In one engagement on November 2nd, 1944, P38s of the 49th Fighter Group destroyed 26 Japanese aircraft without loss. Such one-sided victories had become routine. The strategic bombing campaign against Japanese bases was enabled by P38 escort. B-24 Liberators could reach targets throughout the Southwest Pacific, knowing lightning escorts would protect them. Japanese interceptors, unable to reach the bombers altitude when P38s were present, were reduced to ineffective attacks on the margins. Air bases, fuel depots, and supply centers were systematically destroyed.

The reconnaissance variant of the P38, designated F5, provided crucial intelligence throughout the campaign. Flying at extreme altitudes with cameras replacing guns, these photo lightnings mapped every Japanese installation in the Pacific. Their speed and altitude capability made them nearly impossible to intercept. The intelligence they gathered enabled precise targeting of subsequent attacks. By early 1945, Japanese air power in the Southwest Pacific had effectively ceased to exist. The few remaining experienced pilots had been withdrawn to defend the home islands.

Replacement pilots with minimal training and obsolete aircraft were sacrificed in futile defensive actions. The P-38 had achieved not just air superiority, but air supremacy. The human cost differential was staggering. Between December 1942 and January 1945, P38 units in the Southwest Pacific claimed over 1,500 Japanese aircraft destroyed in verified combat. American P38 losses to enemy action totaled fewer than 200 aircraft. The kill ratio exceeded 7:1, unprecedented in aerial warfare. Beyond statistics, the P38’s impact was transformational. It proved that technological superiority, properly employed, could overcome numerical disadvantage and enemy experience.

It demonstrated that air superiority was not about dog fighting, but about controlling the engagement parameters. It showed that industrial capacity and training systems were as important as courage and skill. Veterans on both sides remembered the Lightning with mixture of awe and respect. American pilots praised its versatility, reliability, and overwhelming performance advantages. Japanese pilots recalled it as the aircraft that ended their dominance, the twin boomed devil that could not be caught or escaped. Ground crews appreciated its rugged construction and maintainability despite complex systems.

The influence extended beyond World War II. The P38’s success influenced postwar fighter development worldwide. The concept of vertical maneuvering became fundamental to jet age combat. The importance of altitude and speed over turning ability shaped designs from the F86 Saber to modern fifth generation fighters. The integration of technology, tactics, and training that the P38 exemplified became the template for Air Force development. Loheed’s design team, led by Clarence Kelly Johnson, had created more than just a successful fighter. They had revolutionized aerial warfare.

The P38’s unique configuration, born from the need to house two engines and turbo superchargers, had produced capabilities that single engine fighters couldn’t match. Its concentrated nose arament eliminated convergence problems that plagued wing-mounted guns. Its twin engine redundancy provided safety over vast Pacific distances. The pilots who flew the Lightning wrote their own chapter in aviation history. Richard Bong’s 40 victories stood as the American record for aerial combat. Thomas Maguire’s 38 victories and tactical innovations influenced fighter doctrine for generations.

Dozens of other P38 aces demonstrated that with proper equipment and training, American pilots could dominate any aerial battlefield. The Japanese pilots who faced the lightning showed remarkable courage in impossible circumstances. Flying obsolete aircraft against overwhelming technological superiority, they continued fighting long after hope of victory had vanished. Their testimony about the P38’s impact provides invaluable historical perspective on the air wars evolution. The physical legacy remains scattered across Pacific islands. crashed P38s and Japanese fighters dot jungles and lagoons from New Guinea to the Philippines.

Each wreck site represents young men who fought and died in a struggle that shaped the modern world. Local inhabitants still discover ammunition, instruments, and personal effects that testify to the intensity of these aerial battles. Museums worldwide preserve examples of the P38 Lightning. Restored aircraft fly at air shows, their distinctive twin boom silhouette instantly recognizable. Veterans gather to share stories of missions flown and friends lost. Historians continue studying the campaigns where the lightning proved decisive. The aircraft that shocked Japanese pilots in 1942 remains an icon of American aviation achievement.

Modern military doctrine still reflects lessons learned in those Pacific skies. Altitude and speed remain fundamental to fighter combat. Technological superiority must be matched with proper tactics and training. Industrial capacity and logistics determine sustained combat capability. The integration of intelligence, technology, and operations that enabled the Yamamoto mission remains the gold standard for precision strikes. The transformation from December 1942 to early 1945 was complete and irreversible. The skies that had belonged to the Zero now belonged to the Lightning.

Japanese naval aviation, which had begun the war as perhaps the world’s most capable air force, had been systematically destroyed. The myth of the invincible zero pilot had been shattered by American technology and training. In the final analysis, the P38 Lightning’s impact transcended mere victory. It represented American industrial democracy’s answer to military authoritarianism. It proved that innovation could overcome tradition, that technology could triumph over experience, that systematic superiority could defeat individual skill. The twin boommed fighter that Japanese pilots initially dismissed had changed the nature of aerial warfare forever.

The Solomon Islands campaign where the lightning first shocked Japanese pilots became the crucible where modern air combat was born. Every jet fighter that followed, every missile engagement beyond visual range. Every precision strike guided by intelligence traces its lineage to those desperate battles above tropical islands. The P38 didn’t just win a campaign. It transformed the very nature of aerial warfare. For the Japanese pilots who survived, the memory of facing P38s remained vivid decades later. In post-war interviews, veterans described the helplessness of watching twin boommed shadows diving from unreachable altitudes.

They recalled the frustration of perfect deflection shots falling short because the lightning was simply too fast to lead properly. They remembered friends and mentors falling one by one to an enemy that redefined the rules of combat. American veterans remembered differently. They recalled the confidence that came from flying the best fighter in the Pacific. They remembered the satisfaction of executing perfect diving attacks while maintaining complete control of the engagement. They recalled the relief of twin engine safety over vast ocean distances and the advantage of always holding the high ground.

The P38 Lightning had not merely defeated Japanese air power. It had revolutionized aerial combat itself. In the skies above the Solomon Islands, between December 1942 and the wars end, the future of air warfare was written. That future belonged not to the most maneuverable fighter or the most skilled pilot, but to the nation that could produce superior technology, train effective pilots, and sustain prolonged campaigns. By war’s end, the P38 Lightning had shocked, dismayed, and ultimately destroyed Japanese air power in the Pacific.

The twin boommed fighter that Japanese pilots had learned to fear had systematically eliminated their ability to contest control of the skies. In doing so, it had secured American air superiority and hastened the end of the Pacific War. The revolution it began in those desperate battles continues to influence aerial warfare today. A lasting testament to American innovation and the courage of the pilots who flew the Lightning into history. Unnecessary repetition while maintaining the target word count and narrative impact.