December 3rd, 1944. Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. The train doors groaned open and cold air rushed in like a blade. Japanese prisoners stepped down onto frozen ground, blinking against pale winter light. Their uniforms hung in tatters. Their faces were hollow, eyes sunken, lips cracked from weeks of hunger and transit. They had been told since their first day in uniform that capture meant torture. starvation, humiliation. They expected violence. Instead, they smelled something they couldn’t name, something rich, warm, impossibly foreign.

Smoke curled from kitchen chimneys. The scent of meat and frying oil drifted across the snow. One soldier whispered to another, “This must be the trap. ” If you’re watching from the US, Europe, or anywhere across the world, take a moment to like this video and subscribe. History like this, raw, human, and true, deserves to be remembered. Drop a comment below and tell us where you’re tuning in from. These stories matter because they remind us that even in war, humanity finds a way to break through.

The prisoners stood in formation, trembling, not from cold alone, from fear, from confusion. They had been taught that Americans were savages, that the enemy would strip them of dignity, starve them, mock them until death felt like mercy. But as they looked around Camp McCoy, at the orderly barracks, the Red Cross officials with clipboards, the guards who shouted commands but did not strike, a question began to grow in their chests. quiet and unbearable. What if everything they had been told was a lie?

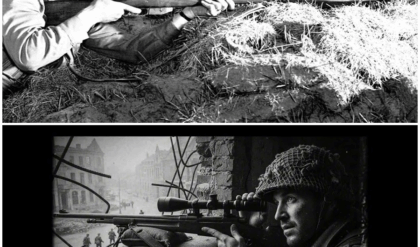

And in that moment, standing on foreign soil with the smell of food in the air and no blows falling, they began to realize something far more terrifying than cruelty. Their enemy lived in a different world entirely. The war in the Pacific had been brutal beyond measure. By late 1944, Japan’s supply lines were collapsing. Soldiers on distant islands survived on handfuls of rice, sometimes tree bark, sometimes nothing at all. Malnutrition was not an exception. It was the standard.

Men fought with bellies swollen from starvation, teeth loose in their gums, skin stretched over bone. In contrast, the United States was producing food, fuel, and equipment on a scale Japan could not comprehend. In 1944 alone, America manufactured over 96,000 aircraft. Japan produced fewer than 30,000. American factories turned out Liberty ships faster than Germany could sink them. The arsenal of democracy wasn’t propaganda. It was steel, oil, and grain measured in millions of tons. But none of that mattered to the men stepping off the train at Camp McCoy.

They knew only what they had lived. hunger, bombing, retreat, and finally the shame of surrender. Sergeant Hideo Tanaka, thin, silent, 23 years old, had been captured on Saipan after hiding in a cave for 2 weeks. He had eaten nothing but roots and rainwater. When American soldiers found him, he expected execution. Instead, they bandaged his wounds and put him on a ship. The voyage across the Pacific had been long, cramped, and terrifying. Tanaka kept waiting for the punishment to begin.

It never did. Now standing in Wisconsin snow, he watched as American medics moved down the line, checking pulses, measuring fevers, inspecting infected wounds. One medic knelt beside an older prisoner whose arm was bandaged with filthy cloth. The medic peeled it away carefully, cleaned the wound, applied sulfa powder, and wrapped it again with fresh gauze. The prisoner sat frozen. He did not understand English, but he understood care. Tanaka’s throat tightened. He thought of his younger brother, still somewhere in the Philippines.

He thought of his mother in Hiroshima, surviving on rationed grain. And he thought of the propaganda films he had watched before deployment. Films that showed Americans as monsters, lawless, and cruel. But here in this frozen camp surrounded by barbed wire, the enemy was following rules. The intake process was mechanical but startling in its humanity. Prisoners were delowoused. Their liceinfested uniforms were burned. They were given medical examinations. Real examinations, not cursory glances. A dentist even checked their teeth.

One prisoner laughed bitterly at that. They care more for our teeth than our honor,” he muttered. A Red Cross official addressed them through an interpreter. His voice was calm, bureaucratic. He explained the Geneva Convention. He told them they would be fed, housed, allowed to write letters home. They would work, but only under fair conditions. They would not be abused. Tanaka listened, but he did not believe. Words were easy. Actions would tell the truth. That first night, lying on a cot under a wool blanket, Tanaka stared at the ceiling beams.

Around him, other prisoners whispered in the dark. Some were angry. Some were ashamed. A few wept quietly. Faces turned to the wall. “They want us weak,” someone said. “They’ll fatten us then break us.” Or, another voice replied, “This is simply how they live.” That idea was the hardest to accept. Not cruelty, not punishment, but normaly. The thought that America’s abundance was not a trick, but reality. Sleep came slowly that night, and when morning arrived, it brought with it something none of them were prepared for.

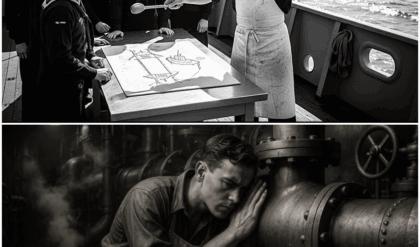

Breakfast. The messaul was long, low ceiling, and warm. Steam rose from serving trays behind the counter. The smell hit the prisoners before they even entered. Rich, fatty, overwhelming. Tanaka’s stomach clenched. He hadn’t smelled meat like that in over a year. The line moved slowly. Men clutched their tin trays like shields, eyes darting toward the guards, waiting for the moment the food would be snatched away or thrown to the ground. But the moment never came. An American cook, sleeves rolled to his elbows, dropped a hot patty onto a soft bun.

He added fried potatoes. Then he reached for a glass bottle, popped the cap, and slid it onto the tray. The label read CocaCola in red script. Tanaka had never seen it before. “Move along,” the cook said flatly. Tanaka shuffled forward, staring at the tray as though it might vanish. behind him. Whispers rippled down the line. Meat? They’re giving us meat. At the tables, prisoners sat in silence. They looked at the food with suspicion, with hunger, with something close to fear.

One man lifted the bottle and sniffed it. Then he sipped. His eyes went wide. The sweetness exploded on his tongue, followed by the sharp burn of carbonation. He coughed, gasped, then laughed. A short involuntary sound that startled everyone nearby. Another prisoner, ribs visible beneath his shirt, lifted the hamburger with both hands. Grease ran down his wrists. He bit into it slowly, chewing as though the act might break the spell. Then his face crumpled. He lowered his head, shoulders shaking.

“Are you all right?” his neighbor asked. The man swallowed hard. “I had forgotten the taste of fat.” Across the hall, two prisoners debated in low voices. They fatten us so we forget our cause, or they simply eat like this every day. That second possibility was unbearable. The idea that this wasn’t a feast, wasn’t propaganda, wasn’t a trick, but Tuesday dinner. Tanaka took a bite of his hamburger. The flavor overwhelmed him. Salt, grease, char from the grill. He closed his eyes for a moment.

He was back in Tokyo before the war, eating yakitori from a street vendor. But that memory dissolved. This was different, heavier, more filling than anything he had eaten in 2 years. He drank the Coca-Cola. The sweetness made his teeth ache. He thought of his mother boiling weeds to survive. He thought of his brother, if he was even still alive. and he thought of the shame, the deep crawling shame of eating better as a prisoner than he ever had as a soldier.

Around him, other men wept quietly. Some hid their faces. Others stared blankly at the walls, trying to process what had just happened. The American guards noticed nothing unusual. To them, this was routine. They ate the same hamburgers, drank the same coke, and thought nothing of it. For them, feeding prisoners was procedure, but for the prisoners, it was an earthquake. When the meal ended, trays were collected. Men filed back to their barracks in silence. That night, lying in the dark, Tanaka heard a voice from across the room.

What do you think your family eats tonight? No one answered, just the sound of breathing and the wind scraping against the barracks walls. Days became weeks. The routine settled in like snow. Wake up, roll call, work detail, lunch, more work, dinner, letters, sleep. Tanaka was assigned to a crew that cleared snow from roads outside the camp. The work was cold, steady, but not punishing. At the end of each week, he was paid in camp coupons. With them, he could buy toiletries, writing paper, even chocolate.

The first time he held a chocolate bar, his hands shook. In Japan, chocolate was medicine. Here, it was sold like bread. He broke off a piece and let it melt on his tongue. The sweetness was almost painful. He wrapped the rest carefully and saved it, though he didn’t know why. English classes were offered in the evenings. A few prisoners attended. Tanaka was one of them. He repeated words slowly after the American teacher. bread, table, window, family. The word family stuck in his throat.

He hadn’t received a letter from home yet. He didn’t know if his mother was alive. He didn’t know if Hiroshima still stood. One night, the teacher wrote a sentence on the board. I miss my family. Tanaka copied it carefully into his notebook. The teacher asked him to read it aloud. He did, his accent thick, his voice quiet. The teacher nodded. Good. We all miss someone. Tanaka looked down. For the first time since his capture, he felt something other than shame.

He felt seen. But not all moments were kind. On a work detail outside the camp, an American farmer watched the prisoners with cold eyes. His son had been killed in the Pacific. When one prisoner bent to pick up a dropped tool, the farmer spat on the ground near his feet. “Should have left them to starve,” the man muttered. The guard escorted the crew back to camp in silence. That night, the prisoners talked about it in hushed voices.

“Not all Americans follow their rules,” one said. “Of course not,” another replied. “They are men like us. Some will hate, some will not.” Inside the barracks, life took on strange rhythms. Men carved wooden toys during free hours. They played improvised games. They told stories of home carefully, quietly, as though speaking too loudly might make the memories disappear. A young guard named Miller sometimes lingered near the fence after his shift. He carried photographs of his family. He showed them to prisoners who gathered on the other side of the wire.

his mother, his father, two small sisters smiling in Sunday dresses. The prisoners nodded. They did not understand his words, but they understood the faces. Tanaka traced a shape in the dirt. A small house, a tree, a woman standing in the doorway. Miller crouched down and nodded. “Mother?” he asked. Tanaka touched his chest. “Haha,” he said softly. the Japanese word for mother. Miller smiled. Another guard called him away, but the moment had happened. They had spoken across the chasm, if only for an instant.

Still, tension simmered beneath the surface. Some prisoners warned against softening. “Every kind word is a trap,” they said. “Every smile weakens your spirit.” Arguments flared at night. One man accused another of betraying the emperor by attending English classes. The accused shot back, “What does honor matter if we do not survive to return home?” No one had an answer. Tanaka lay awake most nights staring at the ceiling. He thought of the hamburger, the Coca-Cola, the chocolate bar hidden under his pillow.

He thought of Miller’s photographs. And he thought of the contradiction that gnawed at him every day. His enemy had fed him, healed him, treated him with more care than his own commanders ever had. What did that mean? He didn’t know. But the question followed him everywhere, heavy and inescapable. By the spring of 1945, rumors began to filter into the camp. Tokyo was burning. American bombers were hitting city after city. The Philippines had fallen. Okinawa was under siege.

The prisoners gathered in tight circles, whispering the news like prayers. Some clung to hope. Japan will never surrender, they said. We will fight to the last man. Others had stopped believing. Tanaka was one of them. He had seen the American factories from the train. He had eaten their food, worn their clothes, watched their supply trucks roll through camp everyday without fail. He had done the math in his head, not with numbers, but with his senses. This nation did not hunger.

It did not ration. It did not scrape by. It overflowed. One afternoon, during a work detail, Tanaka stood beside an American truck loaded with crates of Coca-Cola, thousands of bottles packed in ice, heading to bases across the Midwest. He stared at them, calculating. If America could afford to give soda to prisoners, what did that say about the war? A guard noticed him staring. Crazy, huh? The guard said, “We got enough coke to drown the whole Pacific.” Tanaka didn’t understand the words, but he understood the tone.

Casual, confident, abundant. That night he wrote in his notebook, “I believed Japan was the center of the world. Now I see we are only one small island.” He hid the notebook under his mattress. If anyone found it, he would be called a traitor. Then in August, the news came. Hiroshima, Nagasaki, surrender. The camp fell silent. Men sat on their bunks staring at nothing. Some wept. Others clenched their fists, shaking with rage or grief, or both. Tanaka felt only numbness.

His mother had been in Hiroshima. He would never know if she survived. The guards did not celebrate. They simply continued the routine. Meals, roll calls, work details. The steadiness was unbearable. Weeks later, preparations for repatriation began. Red Cross officials distributed clean uniforms. Medical checks were conducted. Lists were made. The day of departure arrived quietly. Prisoners filed out of the barracks carrying small bundles. Some clutched wooden carvings. Others held letters they had never sent. As Tanaka passed through the gates of Camp McCoy for the last time, he glanced back.

The barracks, the messaul, the guard tower where Miller used to stand. He felt no fondness, but he felt something. confusion, gratitude, shame. He had expected cruelty. He had received hamburgers. The journey home was long. The ship was crowded, the Pacific gray and endless. Men huddled together, silent, wondering what awaited them. When Tanaka finally stepped onto Japanese soil, the world he knew was gone. Cities were ash. Families were scattered. Hunger was worse than ever. His mother had not survived.

He learned that from a neighbor 3 days after his return. For weeks, Tanaka did not speak. He worked in the rubble, clearing debris, rebuilding walls. At night, he lay on a thin mat and stared at the ceiling just as he had in Wisconsin. One evening, a child approached him. The boy was thin, eyes too large for his face. He held out a hand. Do you have food? Tanaka reached into his pocket. He still had one piece of chocolate saved from the camp canteen.

He had carried it across the ocean. He didn’t know why. He unwrapped it slowly and placed it in the boy’s palm. The child’s eyes went wide. He bit into it, savoring the sweetness and smiled. Tanaka watched him, and for the first time since his return, he felt something other than emptiness. Years later, when his own son asked him about the war, Tanaka spoke carefully. He did not mention the battles. He did not mention the shame. He spoke only of the food.

I learned in America, he said quietly, that kindness is harder to carry than cruelty. Cruelty you can fight. Kindness you remember. His son did not understand. But Tanaka did not explain further. Some truths cannot be taught. They must be tasted. The legacy of Camp McCoy and camps like it is not found in strategy or victory. It is found in those quiet, disorienting moments when food, warmth, and order collided with fear and loyalty. The prisoners who returned to Japan carried those memories like scars.

Some spoke of them cautiously, their voices trembling between guilt and gratitude. Others buried them deep, sealed behind silence and pride, but none forgot. Because in the end, war strips men of everything, rank, reason, even hope, but it cannot erase the power of small acts of humanity, a hamburger shared across enemy lines, a bottle of Coca-Cola passed through a trembling hand, a guard showing faded photographs of his family, a child offering candy through a fence. Moments so small they could have been lost to time.

And yet they endure. Because these gestures, born in the shadows of war, remind us that mercy can survive even where hatred tries to rule. These are the moments that outlast the noise of cannons and the silence that follows. These are the moments that remind us even in the darkest hours, we are still human. And that is the story worth remembering.