You sure you are in the right place, cowboy? A student sneered as Clayton stepped onto campus in his worn boots and thrift store uniform. The wind at Exit that morning was sharp like the words Clayton had grown used to hearing, cutting through layers that barely kept him warm.

His thrift store blazer hung loose on his wiry frame, and his boots cracked from years of sun and soil made soft thuds on the polished stone pathway. Around him, students moved like silk pressed khakis, leather shoes, scarves with Latin crests. Their laughter rang out in smooth vowels and effortless privilege.

Tutors followed them, speaking in references to Rouso, plankbach. One boy carried a fencing sword in a case that looked more expensive than Clayton’s entire house. Clayton clutched the strap of his canvas bag, handstitched by his mother back home in Tulia, Texas. Inside it, next to a sandwich wrapped in reused wax paper, was a small leather notebook filled with pencil marks, pages of equations, proofs, and handdrawn graphs.

Some of the pages were smudged, a few edges burned from when the barn stove caught fire last winter. He paused in front of the main hall where a bronze plaque read Philillips Exit Academy, founded 1781, and thought of the words his mother whispered before he left. Do not let their clothes or their last names make you forget why they gave you that scholarship, Clayton.

You listen harder than anyone I have ever known. He took a breath, steadying himself, and stepped through the heavy oak doors. The admissions director had called him a once in a generation thinker. A math mind born in dust, not marble. Clayton remembered smiling awkwardly at the compliment, not quite knowing where to put his hands, but also not doubting the truth of it.

It started with rainfall, or the lack of it. Clayton had begun predicting it better than the local weathermen by the time he was eight using handdrawn charts of cloud movement, barometric pressure, and old farmers almanacs. By 12, he was calculating optimal irrigation ratios during the worst drought in decades.

And by 14, he was teaching himself differential calculus from torn pages found at the library dumpster. Now he was 16 and walking through the halls of the most prestigious prep school in America. The first day was a blur of new sounds and alien smells. Lavender soap polished floors, chalk dust and espresso. His assigned roommate Wesley looked up from his MacBook when Clayton entered, eyebrows raised.

“Is this some kind of exchange program?” Wesley asked, glancing at Clayton’s boots. Clayton offered a half smile. “No, just regular admission, same as you.” Wesley scoffed and returned to his screen. At lunch, Clayton sat alone, carefully unfolding his sandwich. His eyes wandered around the room, catching snippets of conversation.

Did you finish the Uklitian set already? I had my tutor help with number six. My dad says I should not apply to Yale. Too predictable. I told coach I would only row if we made nationals again. Then a voice cut through the noise loud enough for the whole table to hear, “Hey, cowboy, they got corn dogs here, too, or you brought your own crop.” Laughter followed sharp and unkind.

Clayton did not look up, but that night, in the quiet of the dorm room, while Wesley snored softly, Clayton opened his notebook and flipped to a fresh page. The lamp above his bed was dim and the graphite glinted faintly as he began to write. Given a continuous function fde defined on the interval AB with F A FB of opposite signs, there exists at least one C and a B such that F C0 intermediate value theorem. He paused.

Then below it wrote a small note to himself. When two extremes do not agree, there must exist a point where truth balances. Each night the same ritual. While others played online chess or video chatted in French, Clayton wrote proofs, sometimes revisiting old ones from his grandfather’s Navy manual, sometimes inventing his own.

His mind did not race. It listened. It listened to numbers the way his father had listened to the soil gently, patiently until it spoke back. Back in Tulia, there was never enough of anything. Not money, not time, not quiet, but there was love and gestures and warm biscuits wrapped in towels.

In the way mama kissed his forehead without words in the rough, calloused hands of Papa before he passed from the lung sickness. Clayton had seen things crumble, barns, old cars once, even his own faith. But numbers, they never cracked. They either balanced or they taught you why they did not. His first class at exit was advanced theoretical mathematics.

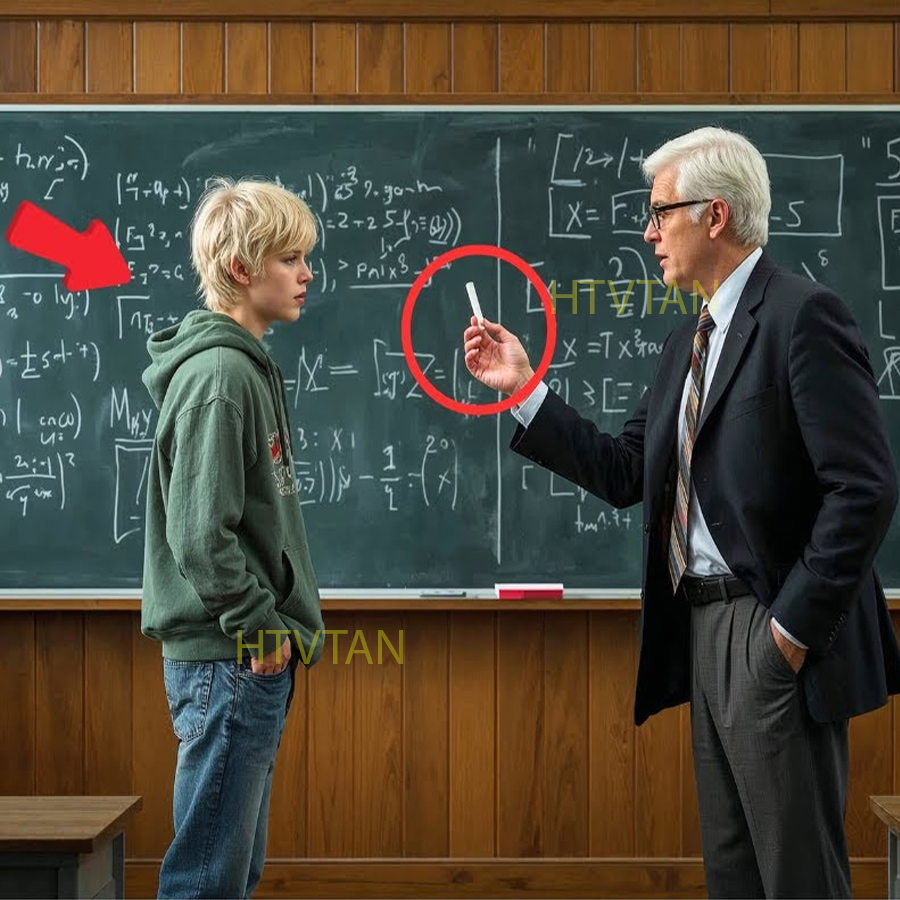

Professor Whitmore was a tall man with a tie that seemed permanently crooked. He spoke with precision like chalk clicking against a board. Welcome to the deep end, he said without smiling. We are not here to solve equations. We are here to understand their language. As he scribbled an equation on the board, Clayton leaned forward.

partial derivative with respect to x second order nonlinear. His fingers twitched slightly instinctively after class while others packed their bags. Clayton remained seated, eyes fixed on the board. You have a question? Mr. Reed Whitmore asked. Clayton hesitated. The coefficient in the second term seems inconsistent with the boundary condition you gave earlier.

Whitmore turned, blinked once, then slowly erased the second term and rewrote it. “Good catch,” he said too calmly. Outside, a student whispered. “Did that farm kid just correct Whitmore?” But Clayton did not smile or smirk. He only looked once more at the board as if solving it again silently.

Later that evening, he wrote in his notebook, “Even in ivory towers, people make mistakes, but numbers they wait for anyone who dares to see clearly.” He closed the notebook, placed it gently under his pillow, and turned off the lamp. Outside, the wind rustled through trees planted by generations, who never knew someone like him would one day walk beneath them. And yet he had arrived.

The boy from the dust, the silence and the equations. And he was just getting started. Hook. Mr. Reed. Perhaps your online tutorials prepared you for this. The professor said smuggly, pointing to the board. It was the third week of term, and Clayton had already become a quiet presence in every class, always early, always scribbling in the same worn notebook.

His uniform was still the same pants that did not quite reach his ankles and a shirt with fading seams, but no one laughed anymore. Not aloud, at least. Some had started to watch him. Curious, others kept their distance, unsure what to make of the boy who read Gaus the way others scrolled through Instagram. Advanced Theoretical Mathematics 2 met every Monday and Thursday in room 2011, a cold highse ceiling room with arched windows that overlooked the western quad.

On that day, Professor Whitmore stood by the chalkboard white dust on his sleeves, writing what appeared to be a nonlinear partial differential equation with nested variables and conflicting boundary conditions. The room fell into a hush as the last symbol was drawn a quiet challenge between the sharp lines of chalk and the minds sitting beneath it.

This Witmore said, turning slowly to face the class is an equation I expect none of you to solve. It is meant to illustrate complexity, not yield answers. A few students exchanged nervous glances. Others reached for their laptops but paused, not knowing where to begin. Whitmore glanced at Clayton, then added, “Mr. Reed, perhaps your online tutorials prepared you for this.” It was not a question.

It was a provocation. Clayton looked up, surprised by the attention. He blinked once, then twice, and stood slowly walking to the board with his notebook still in hand. He studied the equation, lips moving slightly as he read, then looked at the side conditions and boundary terms.

The equation was a trap cleverly built, designed not to be solved, but to frustrate any attempt to simplify it. A hidden contradiction in the boundary values ensured any direct approach would fail. Clayton stepped back, rubbed his chin, then opened his notebook, and turned to a page marked with a folded corner. Sir,” he said quietly, “I believe this can be approached with what I call the cascade method.” Whitmore raised an eyebrow.

“The what?” Clayton walked to the edge of the board and began rewriting the equation line by line, but with changes. He split the nested variables into a sequence of functions cascading in decreasing degrees of complexity and used auxiliary limits to trap the contradiction and resolve it indirectly.

He spoke as he wrote not performing not grandstanding just thinking aloud. If we define fi subn as the transformation kernel and constrain it under conditional convergence, then the contradiction at the outer boundary can be reframed as a false assumption of uniformity. He paused, erased a line, rewrote it that yields a solvable path, though it is non-cononical. The room was silent.

One student whispered, “Is he solving it?” Another Sarah Chun leaned forward. Where did you learn that substitution? She asked softly. That is not in any book I have ever seen. Clayton glanced at her. I was working on a similar form. Last year trying to model soil salinity across fluctuating rainfall zones.

The equation never fully cooperated. So I built a method to step around the instability. Whitmore took two steps closer. now staring at the board with narrowed eyes. “This method, the cascade method,” you said. “Why that name?” Clayton shrugged slightly. Each step falls into the next like water down terraces. It finds its own level. A ripple of something unspoken moved through the room.

Admiration, confusion, perhaps even awe. When Clayton stepped back from the board, the entire left side was now filled with his writing, a full proof in progress and a result forming from the base assumptions. Whitmore stared at it for a long moment, then turned to the class. You are dismissed. All but you, Mr. Reed.

The students gathered their bags in quiet murmurss, several glancing back over their shoulders as they filed out. When the door closed, Whitmore folded his arms and turned to Clayton. That equation, he said slowly, was mine from my doctoral thesis in 1982. I built it to test resilience in symmetry breakdown models. No one has solved it because I made sure the conditions were unsolvable by design.

Clayton looked down. I did not mean to disrespect the problem, sir. Whitmore raised a hand. I did not say you disrespected it. I said you solved it. That Mr. Reed is far more disruptive. He paced slowly before continuing. Why did you not ask for help or a textbook or guidance? Clayton answered simply. I did not know anyone to ask.

Back home, it was just me and the numbers. Whitmore exhaled sharply. There was no contempt now, only disbelief. I do not say this lightly, he said, but I would like to see your notebooks. All of them. Clayton hesitated. Then, with quiet trust, he handed over the worn canvas bag and watched as the professor carried it to his desk.

Whitmore opened the first notebook, then the second, flipping through pages that held proofs, diagrams, personal annotations, even pages of failed ideas labeled with words like rethink or try again. There were derivations of theorems with margin notes like this, feels wrong or too clean to be true.

Halfway through the third notebook, Whitmore closed it gently and looked at Clayton. Who taught you to think like this? Clayton paused. My mama taught me to listen. My papa taught me to notice small things and the rest. The rest came from not having much else. Whitmore nodded slowly as though something inside him had shifted. I want to work with you, he said quietly.

not just teach you, work with you if you are willing. Clayton blinked, unsure what to say. Why? Because the professor said, “I have spent most of my life thinking the next great mind would come from Cambridge or Stanford. But now I think maybe, just maybe, it came from a Texas cornfield instead.

” That evening, Clayton sat alone by the library window, watching the sunset spill golden light across the quiet campus. He held a new notebook, its cover still stiff, and on the first page, he wrote, “The numbers do not care where you come from, only how closely you listen.” Behind him, footsteps approached. Sarah Chun stopped beside the table.

You embarrassed him,” she said, but somehow made him grateful for it. Clayton smiled softly. “I did not mean to. I just wanted to understand.” She sat across from him, curious now, drawn in. “Can you show me how that method works again?” And so they worked, their heads bowed together under fading light, while outside the old trees swayed gently in the breeze.

Whitmore, alone in his office, flipped once more through Clayton’s pages, stopping at a scribbled note beside a failed proof. The numbers are still whispering. I just have to listen better. He closed the book and looked out the window. Something stirring in his chest that he had not felt in decades. Hope.

In a school built for legacies and names carved in stone, something new had taken root. A boy in old boots had begun to rewrite the terms of genius. Where did you learn that substitution? Sarah Chun gasped. That is not in any book. The days after Clayton’s impromptu lecture were different. Students began to linger after class, not just to talk with the professor, but to look at the boy who had rewritten what they thought was unmovable.

Clayton did not walk differently, did not speak more, but there was something unmistakably new in the air. Curiosity mixed with caution. Some admired him, some doubted him, and many just did not know what to think. The next week, Professor Whitmore did something unprecedented. He invited Clayton to the front of the class at the start of the lecture.

No announcement, no introduction, just a nod toward the chalkboard. Clayton looked surprised, but he stepped forward, chalk in hand, his sleeves still a little too short, his boots still cracked, but now every eye was on him. He drew an integral, then a second one nested within it. Then he added variables with dependency conditions and an inequality constraint.

This is a variant of the Putinham problem from 2006,” he said quietly, but with a twist. I found a similar form while modeling evaporation rates across layered soil beds. Someone chuckled under their breath, but Sarah Chun leaned forward, whispering to the girl beside her. “He’s not kidding.” Clayton continued laying out what he called a layered substitution.

one function nested within another treated not as a composite but as a cascading limit. He used a small box to sketch a graph, lines curving like slow water. He walked through it as if the math were a landscape describing not just the numbers but their rhythm, their texture, their hesitations. When he finished the room was quiet. Whitmore approached the board studying it. This, he said slowly, is not standard practice.

Not in any course I have seen. Clayton nodded. I know. It just came out of needing to make sense of something. No textbook covered. Sarah raised her hand. You built a solution method from scratch. Clayton shifted slightly, uncomfortable. I do not know if it counts as a method.

It is just how I saw the problem fall apart when I changed how the constraints behaved. Another student, James Quan, frowned. So, is this mathematically rigorous or just a good guess? Whitmore turned to the class. Let us test it. Homework. Prove or disprove the validity of the cascade method using known theorems and assumptions. Do next class. Groans. filled the room, but underneath there was a spark. Something was moving.

That night, Wesley knocked on their shared door before entering, surprising Clayton. “You uh want help with the problem set?” Wesley asked awkwardly. Clayton looked up from his notebook. “You want to work together?” Wesley shrugged. “Just want to see if this cascade thing is real, that’s all.” Clayton smiled slightly.

Sure, let’s look at it. For the next hour, the two boys sat side by side, bent over the same equations. Wesley found flaws. Clayton adjusted. They argued over definitions, rewrote terms, and slowly slowly something like respect began to bloom. Elsewhere on campus, Sarah Chun sat with two friends under a lamp light outside the library, scribbling equations, debating the implications of variable nesting versus functional independence. This shouldn’t work, one said.

It breaks structure, but it does work. Sarah replied, I don’t know how yet, but it does. The next day, Whitmore entered the faculty lounge holding three student papers in his hand. He laid them gently on the table before Dr. Lindstöm, the head of the mathematics department. These, he said, are variations on a method I believe is new. Dr.

Lindstöm adjusted his glasses. And you think it is publishable? Whitmore hesitated. I think it is the kind of thing that in 10 years might be cited in graduate work. He told her about the boy about the cascade method about the soil. Salinity model turned theoretical proof and he added quietly, “I once told myself the greatest threat to rigor was improvisation, but now I wonder if that was just fear of losing control.” That afternoon he asked Clayton to stay after class.

“You said this method came from a soil model,” he began. “Could you show me?” Clayton opened his notebook, flipped to a dogeared page, and pointed to a set of variables marked with notes in the margins. It started here. We were trying to save water, so I modeled moisture absorption rates over a week using layered differential thresholds, but the math was unstable.

The inputs kept breaking the system, so I stepped them down until they converged slowly. Whitmore listened carefully, nodding more than speaking. For someone who had spent his life in lecture halls, he was discovering the power of being silent. At last, he said, “You are describing a method of constrained descent across non-homogeneous systems,” Clayton blinked. “Is that what it is called?” “It is now,” Whitmore said softly.

He walked to the window and looked out at the fall leaves turning in the quad. “Mr. to read. I would like to mentor you formally, not just for class, but for the National Math Olympiad selection. Clayton froze. The Olympiad. Me. Whitmore turned eyes sharp. You have a mind built for deep structure and a heart that does not yet know what it is worth.

That combination is rare, and it is time. Someone nurtured it. Clayton thought of the field back home of the broken well, the rusted pump, and the notebook his mother sewed together when she could not afford a real one. “If you think I can do it,” he said, “then I will try.” That night he sat by the common room fire, Wesley beside him, both scribbling in silence.

The wood crackled, students murmured in corners, and the wind tapped gently at the windows. Sarah appeared with three cups of cocoa, sat across from them, and said, “All right, cowboy. Explain that last step again.” Clayton looked at them both, smiled sheepishly, and began to draw in the air.

The next week, Whitmore submitted a preliminary abstract of Clayton’s Cascade Method to the Journal of Emerging Mathematical Theories, just to test the waters. To his surprise, a response came within days. This approach appears original and may have applications in numerical modeling. Is the author available for further clarification? But when the editor asked for Clayton’s academic profile, they were confused. The address listed was not a home.

It was a shelter for displaced families outside Amarillo. Whitmore stared at the reply hands frozen on the keyboard. He had known vaguely that Clayton came from poverty, but he had not known it went that deep. That night, he sat in his office long after the halls had gone quiet, rereading every line Clayton had written, every handdrawn proof, every attempt marked with failure and persistence.

“This boy,” he whispered to himself, came here with nothing but a pencil and a will to understand. And now he might just change how we teach math. He picked up the phone and dialed a colleague at MIT. “You remember that old joke we had about the next great method coming from a kid with no shoes?” Whitmore said. “Well, I think he just walked into my classroom boots and all Monday morning arrived with rain tapping gently on the windows of room 2011.

” The sky hung low, heavy with mist, and the usual energy of extor’s hallways seemed muted, subdued. The students filed into class quietly, umbrellas dripping whispers dampened by the weight of weather and something else anticipation. Clayton entered last, as he always did, not out of habit, but respect.

His boots made soft thuds on the lenolium floor. His canvas bag swung lightly at his side, and his notebook, everpresent, was tucked beneath his arm. Whitmore stood at the front of the classroom, hands folded behind his back, staring not at the board, but out the tall windows. His tie was straighter than usual, his posture more rigid.

And when he turned to face the class, there was something almost human in his gaze, something uncertain. “Take your seats,” he said, his voice quieter than usual. When they had settled, he spoke again. Last week you were all given a task to examine a new method, a student method, and to determine its mathematical soundness.

Murmurss moved through the room, glances stolen in Clayton’s direction. Whitmore continued, “I have read every paper, every critique, every defense, and I have come to a conclusion.” He paused, then gestured to the board. But first, I need to show you something with measured care. He wrote a differential equation, not unlike the one from two weeks ago, but this time he added a subtle inconsistency in the boundary condition, not overt, but intentional.

To the untrained eye, it looked merely complex, not flawed. Then, without turning, he said, “Mr. to read. Would you join me at the board?” Clayton blinked, then rose, walking slowly, uncertainly to the front of the room. “What do you see?” Whitmore asked, motioning to the equation. Clayton studied it for a long moment.

His eyes moved across the board, up, then down, back again. “Finally,” he said softly, “you wrote the equation wrong on purpose, didn’t you?” The room was still. Whitmore turned facing him fully now. “Yes,” he said. “I did.” He let the words hang in the air, then added, “And I did so with full knowledge that the mistake would entrap most students, confuse them, discourage them, and I especially wanted to see if it would trip you.

” Clayton looked down, then up again, not with anger, but with something quiet or deeper, a sadness that did not accuse. Why, he asked, not accusingly, just honestly, Whitmore exhaled a sound full of years and pride and fear unraveling. Because I did not believe someone like you belonged in this room.” The students shifted some gasping quietly, others frozen because Whitmore went on, “I spent decades believing genius wore a particular face, came from a particular family, spoke with a certain accent, and when you arrived with your dustcovered boots, and that notebook full of unfamiliar logic, I felt threatened.”

Clayton said nothing. “I wrote that equation to humiliate you,” the professor continued. I wanted to prove that you were a fluke, a trick of charity, not a scholar. Clayton still said nothing. But you saw through it, Witmore whispered. You did not just solve it. You understood the flaw. You looked past the surface and saw the lie.

There was silence in the room, a silence full of wait and waiting. Then Clayton finally spoke. My father used to say, “The land does not lie. only people do. Whitmore looked at him. Numbers are like land, Clayton continued. They tell the truth if you listen long enough. Even if someone tries to hide it, the pattern comes back. He paused, his voice steady.

I do not think you are a bad man, sir. Just someone who forgot what truth looks like when it does not wear a tie. Whitmore looked down his throat working. I owe you an apology, Mr. Reed. And perhaps more than that. Clayton nodded. I accept, but not just for me. For every kid who did not get a seat in this room because someone like me looked wrong. The bell rang, but no one moved.

Then Whitmore turned to the class. This school has long prized legacy, tradition, and excellence, but today I ask you to consider a different kind of legacy. He looked at Clayton and for the first time smiled without reservation. The legacy of humility. The students filed out slowly, quieter than they came in, many pausing to glance back at the professor and the boy who had broken his pride without breaking his heart.

Later that evening, Clayton found an envelope slipped under the door of his dorm room. Inside was a letter handwritten in Witmore’s precise cursive, “Mr. read. I have submitted a recommendation to the board that you be formally nominated as extors candidate for the National Mathematics Olympiad. I also intend to work with you privately should you accept to prepare not just for competition but for contribution.

You have not only shown brilliance but grace that is rarer still with sincere admiration. T Whitmore Clayton sat on the edge of his bed. the letter trembling slightly in his hands. Wesley sitting across the room looked up. “You okay, man?” Clayton nodded. “I think so.” “Yeah, you going to do it, the Olympiad.

” Clayton looked out the window at the rain now slowing to a mist. “Yeah,” he said quietly. “I think I will.” Down the hall, Sarah was telling her roommate what had happened in class. He admitted it. just said it in front of everyone. And what did Clayton do? He forgave him. Just like that. Back home in Tulia. Mama was folding laundry when the phone rang. Yes, this is Mrs. Reed.

A pause, her eyes narrowing in concern, then widening in wonder. Oh my goodness. Well, thank you. Yes, I am very proud of him. She hung up, sank slowly into the nearest chair, and pressed a hand over her mouth, tears welling up. In her small house, lit by a single lamp, she whispered, “He did it, baby. You really did it!” And across campus, in the quiet of his office, Whitmore reopened one of Clayton’s notebooks.

He traced a finger along the edge of a page where a small line had been written sideways in the margin. Let the numbers lead, not the pride. He closed the book, stood slowly, and turned off the lamp. In the darkened room, only the chalkboard remained covered in the honest scribbles of a boy who had never meant to change anyone, only to understand, but in doing so, had changed everything.

It began with a russell paper sliding from one desk to another, a whisper of graphite and precision. Clayton had returned a draft to Professor Whitmore, not his own work, but a paper from Whitmore’s past, a 1987 research piece on symmetry and chaos structures in multivariable differential equations. Whitmore turned the pages slowly, then stopped at the margin where Clayton had written a quiet note in pencil.

This transition assumes uniform convergence across all cases. But the third term violates the condition when boundary deformation exceeds normalized scale. At first the professor said nothing, just stared. Then slowly he reached for a pen underlined the section and wrote in the corner, “I missed this three decades ago.

” Across the desk, Clayton waited his face, calm, respectful. Where did you find this? Whitmore asked. The library archives. Clayton said I was looking for work on nonlinear topologies and your name came up. You annotated my paper, Witmore said, still stunned. Not to correct, Clayton replied quickly. Just to understand. Whitmore closed the folder, stared at it like one might stare at a photo of a younger self. This Mr.

Read is what scholars do. Not just solve problems, but deepen them. Word began to spread among the faculty, then the upper classmen. Clayton was not just a clever student anymore. He was being cited. In one week, three professors had asked to borrow his notebooks.

Another requested permission to audit the independent study sessions Whitmore had begun to hold in the evenings. They met twice a week in a quiet seminar room with only a blackboard, two chairs, and stacks of notes. Together, they explored recursive constraints, topological spirals, and integer-based error corrections that could reshape how convergence was taught at the undergraduate level.

One night, Whitmore brought out a folded letter. The Journal of Emerging Mathematical Theories wants to publish your cascade method, he said. Not as a letter to the editor, but as a primary article. Clayton blinked. Me, you, Whitmore said firmly. They want your graphs, your proofs, your soil, evaporation model as the origin story. Everything.

Clayton stared at the letter as if it might vanish if he looked too directly. Do they know I am 16? They know you are brilliant. That is enough. There was a long pause. Then Clayton said, “But what if it is not real? What if I just got lucky?” Whitmore looked at him. You do not stumble into sustained insight, Clayton. What you built is elegant because it had to be born of necessity, of seeing systems fail and wanting to save what you could. Clayton nodded slowly.

The soil back home could not wait for perfect math. Exactly. Later that week, the news broke wider. An academic digest picked up the abstract referencing a new form of functional reduction built from agricultural data and citing an unnamed student at exit.

As the author, Clayton, walked past the bulletin board in the science wing, saw his name printed under a heading that read, “The future of applied logic,” and stopped. So abruptly, Sarah nearly bumped into him. “You saw it,” she said, smiling. He nodded barely. People started asking questions. A few doubted, of course, but the elegance of the work spoke, louder than his boots ever could.

One professor from MIT called Whitmore directly asked if he could be connected with Clayton. Whitmore agreed, but gave only the school mailing address. The next day, a letter arrived addressed in careful print to Clayton Reed, care of Philip’s Exit Academy. Inside an invitation to speak briefly at an upcoming academic symposium in Boston, Clayton read it three times, unsure what amazed him more, that they wanted him to speak or that they spelled his name correctly.

Wesley walked in as he was reading it again. What is that? An invitation to a math conference. you going? I do not know why not. Because I am just me. Wesley frowned. Look, I used to think you were weird. Just being honest, but you are not weird. You are just ahead. Clayton looked down at the letter again.

Whitmore knocked on the door that evening, stepped inside with his usual quiet presence. I heard about the letter, he said. I also heard MIT had your name flagged last year. Clayton looked up, confused. Apparently, a professor there came across one of your old posts in a math forum about rainfall modeling using dynamic integrals.

He said he tried to contact you, but the address listed was a shelter in Amarillo. Clayton went still. How long were you there? Whitmore asked gently. 2 years after Papa, Mama could not keep the farm going. We moved a lot. School was when we could. Whitmore sat down beside him. Clayton, your story is exactly why this work matters. Not just the math, but what it represents. Clayton nodded slowly, folded the letter back into its envelope. Maybe I will go.

If mama says it is okay, she will. Whitmore smiled. Trust me. That Sunday they called home. Mama Clayton said carefully. They want me to give a talk at a university. There was a pause on the line, then her voice soft and steady. Well, honey, I do not know what you are doing out there, but it sure sounds like you are doing it right. Clayton smiled.

I will send you a recording if I do not mess it up. Her voice cracked a little. You have never messed up anything that mattered. The next week, Extor’s newsletter ran a short piece. Student research receives national attention. No mention of the boots or the farm or the boy who used to fix broken sprinklers with coat hangers.

Just Clayton Reed developing new mathematical tools to address fluid dynamics and constraint systems. In the back of the library, Clayton sat by the window, flipping through a journal someone had left open. In the margin next to a complex integral, someone had written in pencil. Looks like a cascade waiting to happen.

Clayton smiled, then reached for his own notebook, opened to a fresh page, and began to write. Not to be known, but to know, not to impress, but to express. Let the math serve not the self. And across campus, Whitmore stood at the podium of the faculty meeting, a slide behind him titled the Clayton Reed Mathematics Initiative.

He spoke not just of method, but of mentorship, of what it means to see past appearance, past tradition, past assumptions. We are not here to guard the gates of knowledge. He said, we are here to open them and wait to be amazed by who walks through. and when they do, we must be ready, not just to teach, but to learn again. The room fell silent and stayed that way, even after he finished speaking.

Back in his room, Clayton received a package by mail. No return address, just a note inside. You are not alone in what you see. Under the note was a rare textbook on nonlinear field equations with margin notes scribbled throughout. The handwriting matched his own from the forum posts years ago. He looked at it and whispered, “I remember this.

” Then quietly he opened to the first page and started reading again. The great hall was packed. Students stood along the walls. Faculty filled the upper balconies and the banners of Philip’s exit academy hung motionless in the still air lit softly by chandeliers that had watched over generations of tradition.

Whitmore stood at the podium, papers in hand, but for once no notes prepared. His eyes scanned the room, found familiar faces, unfamiliar postures, and finally settled on Clayton sitting in the back row alone as always. A ripple of whispers passed through the student body. This was the assembly, the one where they announced who would represent exit at the National Mathematics Olympiad.

The unspoken assumption had always been clear. It would be Timothy Whitmore, the third grandson of the man behind the school’s modern math department, captain of the debate team, and recipient of every private tutor his family’s endowment could fund.

Timothy stood near the front, dressed in a navy blazer, his jaw tight. His father had flown in, seated next to the headmaster, proud and expectant. Whitmore cleared his throat. “Today I stand before you, not just as an educator, but as a student myself.” A few puzzled looks swept across the hall. I have spent most of my life teaching formulas, theorems, methods, and yet this year I learned something I had not expected.

that genius does not only walk where legacy has already paved the way, a murmur soft but growing. He paused, looked directly at Timothy, then to the back where Clayton sat, still eyes lowered. For the first time in 43 years, Extor’s representative to the National Mathematics Olympiad is not a legacy, not a donor’s child, not the product of preparation or privilege.

He is, however, the product of perseverance, of knights, by fire light, of learning through necessity, and of a mind that listens more than it speaks. A long silence, then one clap, then two, then a swell of applause that rolled like thunder, across the great hall. Clayton raised his eyes, confused, at first, then slowly stood, his face flushed, his shoulders still slouched in humility. Students parted to let him through as he walked toward the stage.

Timothy remained standing motionless, expression unreadable. When Clayton reached the podium, Whitmore extended a hand. “Congratulations, Mr. Reed,” he said, his voice steady. “You will represent us all.” Clayton took the microphone, his hands trembling. “I never thought I would be here,” he began, voice quiet but clear. Back home, math was not something people expected you to be good at.

It was something you used to fix broken machines or measure seed. Not something you studied for joy. He looked up the hall, silent now. But here I found people who taught me that numbers can be beautiful, that problems are just stories waiting to be heard. He paused. And if I am up here today, it is not because I am better, but because I listened to the problems to the people who challenged me and to the ones who believed in me when I could not believe in myself. More applause this time, warmer, deeper.

Some students even stood. That night, Whitmore sat in his office reviewing Clayton’s latest notes. The ideas were getting sharper, more daring, touching on principles of unsolved problems in number theory. There were traces of the Reman hypothesis in the margins notes in the corners marked with words like possible correlation or extend from prime twin structure. Timothy knocked once before entering.

His face was still his movements precise. May I sit? Of course, Whitmore said. There was a pause. Then Timothy asked, “Was it ever going to be me?” Whitmore looked at him long and steady. “It was until you stopped asking questions, until you started answering just to be right.” Timothy flinched barely. “I still think I am good.” “You are.

But brilliance without curiosity is a flame without oxygen. It burns fast and dies silent.” Timothy looked down. Then after a moment he asked, “Is he really that good?” Whitmore smiled. “I think I think we are lucky to know him this early.” Timothy nodded once. Just once and then left without another word.

The next morning, Clayton returned to his dorm to find a note taped to his door. “You earned it. Make it count.” Signed T. Later that week, the headmaster called Clayton in, explained the conditions of travel, the academic schedule he would follow, and that a scholarship had been extended through a grant made in his name.

A new name had been etched into the scholarship funds wall that week, the Clayton Reed Mathematics Initiative down in Texas. Mama got another call, this one from a reporter, asking if she had time for a few questions. She laughed nervously. I do not know what to tell you. He was always curious, always quiet. I guess he just listened better than the rest of us. In Boston, preparations began for the Olympiad team.

Clayton was given problem sets beyond anything he had seen before. Some designed to break confidence, some to test imagination. He worked through them one at a time, steady as planting rose. In the late evenings, he wrote to his mother, “Mama, I still wear the boots. I still use the same notebook.

And every time I open it, I remember you saying, “Learn with everything you have because nothing you learn can ever be taken away. The night before he was set to leave for the regional training camp, Whitmore invited him to dinner. They sat in the professor’s home, modest and lined with books, plates of stew between them.

You do not have to win, Whitmore said. You just have to be yourself. Clayton smiled. I think being myself is the only thing I am good at. Whitmore raised his glass to boys who rewrite the rules without trying to break them. Clayton lifted his glass, too. To professors who learn how to listen. Outside the first snow began to fall over exit, gentle and slow, covering the stone paths and the iron gates with soft white.

And in a dorm window a light stayed on deep into the night, where a boy from a broken farm town studied numbers as if they were prayers, because to him they were. It was two weeks before the Olympiad and the regional training camp had transformed from a group study into a crucible.

30 students from elite schools across the Northeast gathered in a quiet corner of Boston, sleeping in dorms, eating at odd hours and solving problems that had never been printed in books. Clayton sat alone most nights cross-legged on a wooden floor with only a desk lamp overhead. His notebook was thicker now, the pages softer from constant turning. Yet his process remained unchanged. He spoke to no one unless spoken to.

He solved each problem as if it held a key to something much larger than a metal. But on the third day of the second week, Whitmore arrived with a sealed envelope. “This,” he said, handing it to Clayton, “is your last simulation before we fly out.” Clayton opened it carefully. Inside was a single sheet of paper.

No instructions, no context, only a problem written in Whitmore’s meticulous hand. Prove or disprove the convergence of the following functional series under recursive asymmetry where boundary values are determined by stochastic phase shifts. Clayton blinked once, then again. Something about the phrasing was familiar. He looked up.

This problem, it is from your private research, is not it. Professor Whitmore nodded slowly. I have been working on it for the past 6 months quietly. No one has solved it. Not yet. Why give it to me? Because Whitmore said, “If you can see its shape, even without finishing it, I will know you are ready for what comes next.

” Clayton nodded, then returned to his desk. He spent the next 4 hours in silence, breaking only to sip water or stand and stretch. The others passed by his door, glancing in. Some scoffed, some whispered. A few, like Sarah, just watched quietly waiting. When he emerged, he handed the paper back to Whitmore.

It does not converge in general, Clayton said. But if you apply a bounded perturbation aligned with a harmonic decay curve, the divergence becomes conditional and therefore directionally interpretable. Whitmore stared at him. That is not a full proof. Clayton shook his head. No, but it is three paths toward one, depending on which assumptions you hold constant.

He reached into his bag, pulled out three pages, each contained a separate attempt. Different assumptions, different methods, but all inching toward resolution. Whitmore took them in silence, reading each line. The camp director stepped in, having overheard the exchange. “What is that?” Whitmore replied without looking up. It is something I once thought I would have to finish alone.

By the next day, word had spread among the students. You heard Reed tackled a Witmore problem. Wait, the Witmore problem, like the one from his unpublished lectures. They say he came up with three solutions. Timothy, who had arrived at the camp late due to illness, found Clayton during a break. You actually worked through his private material.

Clayton nodded. It is just math, not magic. Timothy looked at him. Not with resentment, but something closer to wonder. You know, he said, people like me, we are trained to compete. You, it is like you are just trying to understand the wind. Clayton smiled. It is the same wind. We just hear it differently.

Later that night, Whitmore pulled Clayton aside. MIT wants to meet you in person after the Olympia ad. So does Caltech. Clayton’s brow furrowed. I do not want to leave Mama behind. You will not, Whitmore said. You will bring her forward. Clayton nodded. But part of him was afraid.

Afraid of becoming someone even his past would not recognize. In his room, he sat beside Sarah, who was struggling with a geometry problem involving inversion circles and non uklitian maps. “This part here,” she said, tapping the diagram. “It will not resolve cleanly.” Clayton took a pencil, drew a single curved line through the chaos.

It was a simple substitution, but elegant. Sarah stared. “You see things like that in your head. Sometimes I have studied geometry for four years and I would not have seen that in a hundred tries. He shrugged. I studied shadows on barn walls. Same shapes, just different tools. The last night of camp came quickly. The final challenge was a team test.

Clayton, Sarah, Timothy, and another boy named Levi were placed together. Each student had five problems, all different but tied together through a hidden structure. They worked in silence, then in whispers, then in bursts of urgent clarity. Clayton saw the link first. The fifth problem was a mirror of the first, just disguised with variable inversion and boundary twist.

Once he explained it, the others moved quickly, fitting the pieces together like a tapestry being pulled tight. When the final buzzer rang, theirs was the only team to finish. The director announced it quietly with a nod toward Clayton.

You may not know it yet, he said, but you are about to carry the hopes of a lot more than a school. Whitmore put a hand on his shoulder. Ready? No, Clayton said, “But I am going anyway.” Outside the storm rolled in quiet thunder in the sky, not yet overhead, but coming inevitable. In his room, Clayton wrote another letter home. “Mama, I solved something today that I do not know if anyone else ever solved, but what I really learned is I cannot do it alone.

I need people even if I still do most of the work with a pencil and the quiet. He folded it, placed it on the table, then opened his notebook again. The next page was blank waiting. And in the hallway outside, Timothy stood for a moment, then knocked once, soft, Clayton opened the door. Surprised, I came to ask something. Timothy said, “Sure.

Can you show me how you saw that curve in the last test?” Clayton nodded. Come in. Bring a pencil. And so they sat. Two boys, once rivals, now something different, tracing lines in silence as the wind picked up outside because the storm was coming. But so was the boy who had learned to listen to it.

The hall in Washington DC was unlike any Clayton had seen. A circular ceiling stretched high above rows of long desks polished until they shone. The room smelled faintly of cedar and graphite. The buzz of quiet tension hummed just beneath the surface. 50 students from across the nation each the top of their class had gathered. For one reason, the National Mathematics Olympiad.

Clayton sat at desk 37 near a window where winter light spilled onto the floor in pale gold. He wore his same boots, same faded blazer, and carried the same canvas bag his mother stitched back home. Before the proctors began, Whitmore found him in the hallway, leaned in close, and said, “Do not solve the problems.” Clayton looked up, confused. “Dance with them. Let them lead you.

See where they want to go and listen.” Clayton nodded slowly. He understood. The first hour passed like wind through bare trees. The problems were long, elegant, difficult. One was a combinatoric proof built around recursive partitions. Another a geometry challenge involving rotating conics and dual symmetry points Clayton did not write right away.

He watched the problems like a painter studying an empty wall, waiting for the first brushstroke to feel right. When he did move, it was with quiet clarity he solved. the first using a three-step substitution that turned a tangled equation into a clean loop. The second he rewrote entirely framing it as a topological transformation, letting the shape speak instead of the symbols.

Then came the final problem. Problem six. Let P be a sequence of even integers such that for every n or two, the number n can be written as the sum of two elements in P in at least one way. Prove or disprove that such a P must contain all even integers greater than two. Clayton’s pencil hovered. Goldbach, he whispered.

This is a variant of the Goldbach conjecture. He sat back, closed his eyes. Goldbach had remained unsolved for centuries. The idea that every even number greater than two could be written as the sum of two primes. But this version, while echoing the original, was twisted. It replaced primes with a constructed sequence, giving him more space, more control. He opened his notebook to a blank page.

If I treat P not as a fixed set, but as an evolving series, he thought, and use modular constraints to restrict overlap, I can build an induction framework. He worked silently, pages filling his fingers smudged with graphite. He used harmonic step functions to define his boundaries, then layered a frequency distribution onto the modulus operation, narrowing the cases from infinity down to repeatable clusters.

Each line led to another until almost gently the pattern appeared. A sequence P that excluded some even integers greater than two could still satisfy the condition, but only if the gaps formed a bounded non-re repeating set. He drew the final line. Therefore, not all even integers must belong to P for the condition to hold. A disproof, precise, quiet. The bell rang.

Clayton set down his pencil, breathed slowly, others looked broken, some amazed, a few simply stared. Later that night, the results were posted. Clayton Reed, 42 out of 42. Perfect score. The first in the Olympiad’s 39-year history. Students clapped some, cheered a few, looked stunned, but Clayton only smiled slightly, then went outside where the air was sharp and clean. Whitmore found him there.

They said no one would ever get a perfect score, he said. They were right, Clayton answered. Until today, Whitmore put a hand on his shoulder. You did not just win, you changed what it means to compete. Timothy joined them, handed Clayton a folded note. Congratulations, you earned every digit. Sarah grinned. What did it feel like? Like listening to something I had not heard since I was a kid, Clayton said. Like hearing the rain again after a drought. He called Mama that night from the hotel phone.

You were right, he told her. Nothing I learn can be taken away. There was a pause, then her voice. Baby, I am proud of you. But I always was, even when it was just you and that little flashlight and a stack of old math books from the library shelf. He did not cry, but his voice cracked. Thank you, Mama. She laughed softly.

you coming home soon? Yes, he said. Just a few more things to finish first. The Olympiad committee called the next morning. We want to publish your proof, they said. And we would like to ask if you would consider mentoring future contestants. Me mentor? You understand something most do not, they replied. Not just the math, but the patience.

That afternoon, Whitmore handed him a flight itinerary to California. MIT wants to fly you out. So does Stanford. And Princeton left a voicemail. Clayton blinked. Do I have to pick right away? No, Whitmore said. But they are all listening now. Clayton opened his notebook one more time that night. At the top of the new page, he wrote, “It was never about winning. It was about listening.

” Then he drew the final graph of the proof, tucked the notebook into his bag, and went to bed early because tomorrow he would fly home. And soon he would begin again. The assembly hall at Exit had never been this full. Parents, alumni, faculty, students, even the janitor who always swept the quad at sunrise.

They had come to celebrate the Olympiad team, but they were there for Clayton. The banner read, “National Olympiad Champion.” Clayton Reed in gold letters above the stage. Clayton stood off to the side, shifting nervously in his still too small blazer, holding the worn canvas bag with the notebook inside, the one that had traveled with him from barn to library, from bus stop to Washington DC, from scribbled dreams to published reality.

The headmaster took the podium first, gave the expected speech about excellence and discipline and school pride. Then came the mayor of exit, then a senator, each added a layer of praise, each more distant than the last. Then Whitmore stepped up. The room quieted. Some in the back even stood.

He cleared his throat, adjusted his glasses, and looked directly at the students. I have taught at this academy for 31 years, he began. And I have seen thousands of students pass through these halls, some brilliant, some determined, some both. But I had never seen a student like Clayton Reed. A murmur swept the crowd, and then silence again.

I once believed Whitmore continued that genius came, dressed in certain clothing, spoke in certain accents, lived in certain zip codes. I taught that brilliance looked a particular way. He turned slightly facing the faculty now, but I was wrong. The words landed like a slow storm. He looked toward the back of the stage where Clayton stood, frozen, eyes wide.

The boy you laughed at just solved a problem I have struggled with for six months. The audience turned toward Clayton, then back to Whitmore. Heap did not do it with labs or grants or expensive tutoring. He did it with a pencil, a lamp, and the kind of focus that comes from knowing no one else is coming to help. Clayton looked down, tears burning the edges of his eyes.

“I once tested him,” Whitmore confessed deliberately unfairly, and he passed not just with intellect, but with grace. And in that moment, I realized something about myself. I had become a gatekeeper, not a teacher. He paused, looked out at the rows of students. Let that not be true of any of you.

The applause rose slowly, then thundered louder than any ceremony the school had hosted in years. Whitmore stepped aside and motioned to Clayton, who walked hesitantly to the microphone. He stood for a moment, eyes scanning the crowd, then spoke. Thank you, professor. Whitmore, he said softly. And thank you to everyone here who saw more in me than I could see in myself.

He opened his notebook, looked at a scribbled note. I used to think math was just numbers on a page, something you did to pass a class, but I learned it is more like music. If you listen close enough, the patterns start to sing. Someone in the audience wiped away a tear.

An older alumnist perhaps, or a grandfather who remembered the war, Clayton continued. I am not here because I am better. I am here because I got the chance to learn, and I want that chance for others, too. That is why he paused, glancing at Whitmore. I will be working with Professor Whitmore to create a mentorship program for students from places like Tulia, Texas, and towns you have never heard of.

He stepped back, the applause rising again. Later that afternoon, he sat alone on the steps outside the hall. Sarah came by, handed him a cup of cocoa. That was some speech, she said. I was shaken the whole time. No one noticed Wesley joined them holding a printed copy of Clayton’s Olympiad Solution. This, he said, tapping it made me cry.

Just so you know, Clayton smiled. You cry a lot more than you admit. True. Timothy appeared, hands in his pockets. Hey, hey, you did it, Reed. We did. Clayton replied Timothy hesitated then asked, “Are you really turning down MIT for now?” “Just postponing?” Clayton said, “I have something else to do first.

” The sun dipped behind the trees, painting the stone buildings in warm gold. Inside Whitmore’s office, a plaque had been mounted that morning. The Clayton Reed Mathematics Initiative founded 2025. In pursuit of brilliance through humility, Witmore sat at his desk staring at it, he whispered. I was wrong, but I am grateful to have been.

And in a quiet dorm room, Clayton wrote another letter. Mama, they clapped for me today, but I was thinking about you washing dishes while I practiced equations in the dark. Thank you for believing I could be more than the dust around us. He folded the letter, then opened a new notebook. Page one. Not all storms come to break you. Some come to clear the path.

The airport in Amarillo smelled like dust and fuel and something softer. Memory perhaps. Clayton stepped off the plane alone, his boots hitting the terminal floor with that same quiet thud they had when he first arrived at exit. Only now there was something different in his step. Not louder, not faster, just steadier.

Mama was waiting outside wrapped in her best coat, her hands trembling around a styrofoam cup of coffee. When she saw him, she covered her mouth and wept openly. No shame, no hesitation. Clayton dropped his bags and wrapped her in his arms the way a boy hugs the only constant in a world full of uncertain variables. “You got taller,” she said. “You look the same,” he whispered. “Thank God.

” They drove home in the old pickup truck with one window stuck halfway down and a radio that only played gospel. The sky stretched out like a canvas, half-finished cotton clouds over bare fields. Back at the trailer, nothing had changed, and yet everything had. The porch still creaked, the stove still hissed when lit, but Clayton set his canvas bag gently on the table like it was a sacred object.

That night, over beans and cornbread, he told her about the Olympiad, the plain rides, the halls of MIT, and the plaque with his name. She listened, eyes wide, smile soft, and they clapped. She said, “For you.” He nodded. “But I was thinking about you the whole time.

” The next morning, he walked through town, passing shuttered shops and broken signs. Children played in the dust like he once did, chasing shadows with sticks. He stopped at the library, still open, still quiet. Miss Ellen was behind the desk. Same as always. Well, I will be, she whispered. You came back. Just visiting, he said.

But I wanted to say thank you for what? For never asking why I borrowed the same book 15 times. She smiled. That is what they are for, child. Clayton sat under the pecan tree in the yard that afternoon, notebook in hand, watching the breeze move across the fields. There were no more test scores to chase, no more medals to win, just thoughts to gather and seeds to plant.

He began drafting the first curriculum for the mentorship program, one that would not start with equations, but with stories. Stories like his. That week, he visited three schools in nearby counties, spoke to students in gymnasiums that smelled of chalk and sweat, told them about patterns in dust, about listening to numbers, about how poverty was not proof of anything except how strong you had to be to think beyond it.

At the last school, a boy asked, “Did you ever feel stupid being from here?” Clayton paused, then knelt beside him. I felt invisible. He said, “That is worse, but not anymore.” On the final night, he and Mama sat on the porch watching the stars. “I was offered MIT,” he said. “Full ride.” She looked over. “That is good, right?” “Yes, but” I said, “Not yet.

” “Why? Because there is work here first, real work, and I want to build something before I go.” She nodded slowly, the silence between them full of understanding. You gave up your dreams so I could have mine. Mama, I will not waste that gift. The next morning, he walked to the old barn, swept the floor, fixed the broken hinges, and set up a chalkboard that had once been tossed behind the church.

He painted a sign above the doorway. The field school math logic listening open Saturdays. By the end of the month, seven students were coming by spring. There were 20. Mama made biscuits for all of them. He taught them fractions by cutting apples. Taught geometry by tracing stars. Showed them how math could explain shadows and music and wind.

When MIT called again, he told them, “Yes, but give me one more summer.” They agreed. One evening he received a letter in the mail, thick envelope, Cambridge Seal. Dear Mr. Reed, we would be honored to publish your Olympiad disproof in our upcoming volume on emergent mathematical theory. He smiled, folded it, placed it in a drawer. That night, he wrote one last letter before packing.

Mama, I am going, but I will always come back. The field is part of me now, not as something I left, but something I carry. When he boarded the plane that fall, he brought the notebook, the boots, and a small jar of soil from the backyard. He kept them on his desk at MIT. Years later, when asked to define genius, he said, “It is the courage to keep listening even when no one else hears what you do.

” And when asked where he learned that, he said, “A farm, a porch light, and a mother who never stopped believing.” And though the future had no fence rose, Clayton always knew exactly where home was.