This class isn’t for janitors, kids. Get out. The morning fog clung low over the edges of Pasadena, tracing soft outlines around the oak trees near the campus gates. It was early, just before 7. The glass hallways of Caltech’s engineering division were still quiet, with only the faint sounds of coffee brewing and notebooks flipping open somewhere behind closed doors.

And then there was the boy. He walked with careful steps, not like someone who belonged here, but like someone who was afraid to disturb the silence. His shoes were worn, the kind that had been shined many times over, but still could not hide their age. His coat hung loose over his shoulders.

The stitching was coming apart at the elbows, and in his hand he held a folded envelope, white, creased, and handled many times. He stopped outside room B231. On the plaque beside the door were the words, “Advanced thermodynamics and internal combustion, Professor Margot Richardson.” Elliot Granger was 12 years old. He took a breath, smoothed the front of his coat, and stepped inside.

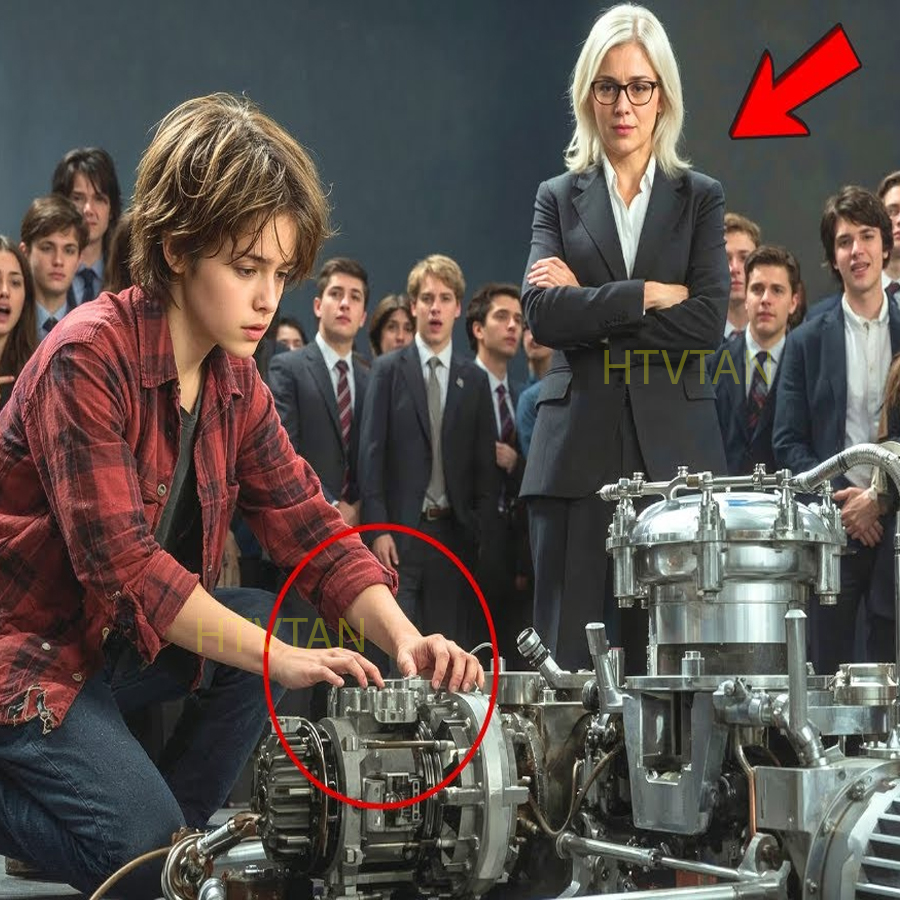

The lecture hall was shaped like a bowl lined with dark wooden desks that sloped downward toward the front where a large steel engine stood behind a row of white boards. The engine had been cut open to show its inner parts, pistons, valves, shafts. Around it were diagrams, formulas, symbols written in firm strokes of black marker. Elliot had never seen anything more beautiful. But then came the voice. “Excuse me,” said Professor Richardson.

She did not shout. Her voice was steady and sharp like cold water. “This class isn’t for janitors, kids. You’re in the wrong building.” Her words fell into the room with a heavy stillness. 30 pairs of eyes turned toward him. Elliot did not move. Slowly, he reached into the pocket of his coat and pulled out the envelope. He held it out, his arms slightly shaking.

“I received a letter,” he said softly. “From the admissions board. I’m supposed to be here.” Richardson did not reach for the letter herself. She gave a small wave of her hand, and a graduate student near the front stood up, took the paper, and passed it forward. There was a long silence while the professor read, then a pause.

“Fine,” she said, folding the letter without looking up. “Back row, do not interrupt.” Elliot made his way past the rows of students. No one smiled. No one moved aside. He found a seat in the very back near a rusted air vent and sat down. From his bag, he pulled out a notebook. Its cover was worn soft from use, and the corners had been reinforced with tape. He opened to the first page.

At the top, in neat, careful handwriting were the words, “Therodnamics is beautiful.” He had written it the night before. The lecture began. Professor Richardson moved quickly, writing equations across the board with steady hands. She explained the first law of thermodynamics. internal energy, heat, work.

She spoke with certainty, not like she was sharing knowledge, but as if she was reminding everyone of things they should already know. Elliot wrote everything down. His pencil moved without pause. He did not look away from the board. The classroom air was dry and cool, and every sound seemed to echo slightly, the clicking of keyboards, the hum of the projector, and the quiet whispers behind his back.

Is that the janitor’s kid? Someone said probably got in through one of those programs. Those shoes look older than my dad. Elliot kept writing. He had heard worse in the hospital waiting rooms in court at the soup kitchen on New Year’s morning when they thought he wasn’t listening.

People always said things when they believed no one important could hear them. But he had learned something from his father. A man who had once repaired the boiler system in that very building, whose name no one remembered, who came home every night with grease on his hands and a quiet pride in his walk. He had taught Elliot that machines never lied. People might.

But if a piston jammed or a valve stuck, the truth would reveal itself always. And so Elliot wrote, “Formula after formula, word after word.” He did not stop to think about the laughter or the stairs. The engine at the front of the room caught his eye again. It was a model, a test engine for combustion research.

Something was wrong with it. He could hear a small metallic rattle just once when the building’s heating system kicked in. It was not loud, but it was wrong. and he had heard it. After the lecture, as the students began to pack up, Richardson closed her notes with a snap and pointed to the engine. “That,” she said to no one in particular, “is a prototype we built last spring.

It failed two of its performance tests. No one has been able to diagnose the issue, but that is not your concern. It will be removed next month.” Elliot waited for the room to empty. Then he walked to the front. He stood beside the engine. It was about the size of a washing machine built from aluminum and steel bolted to a test stand.

He ran his fingers gently along the side, not touching any of the internal parts, just feeling the shape of it. Then he leaned close. He didn’t speak. He listened. There it was again. A faint sound like a loose bearing or a misaligned sleeve. A wrongness. subtle but present. A trained ear might miss it, but Elliot had spent hours lying under junkyard cars, listening to their last breaths before collapse.

He had heard that sound before. “Step away,” said a voice behind him. “It was Professor Richardson.” She had returned without a word. You are not authorized to touch that machine, she said. And it costs more than your house. Probably more than your entire block. I will not have it scratched by a child with curious fingers.

Elliot stepped back. Yes, ma’am. She stared at him. Something unreadable passed through her expression. Not warmth, not forgiveness, but maybe the smallest flicker of attention. You’re here because someone up the chain thought we needed a project. A news story perhaps? I do not have time to entertain fairy tales.

So, if you’re going to be in my class, sit, learn, and do not speak unless asked. Is that clear? Yes, ma’am. She left. Elliot stood alone beside the engine. His notebook was still open in his hand. On the next page, he wrote, “Rattle-on cylinder 2, possible wear or misalignment. Check oil path. Ask about last service date.” He underlined it twice.

Outside, the fog had begun to lift. Sunlight filtered through the tree branches, and the red brick buildings of Caltech looked softer than before. Elliot sat on a bench near the fountain. His pencil traced the outline of a piston assembly with notes scribbled beside each part.

He wrote equations in the margins, arrows pointing toward theories he had only half understood. He did not know if anyone would respect him here. He did not know if the professor would ever say his name without scorn, but he did know one thing. Something inside that engine was broken and he could fix it. They said his shoes were older than the professor. Elliot came back. It was Monday morning.

The sun had barely touched the tops of the eucalyptus trees lining the southern edge of campus. A soft breeze ran along the concrete walkways, carrying with it the faint scent of cut grass and old chalkboards. Inside building 3, room B231, the lecture hall was already half full. Students took their usual seats, some still chewing breakfast bars, some scrolling through their phones. Laptops flickered open.

Voices whispered in short bursts like little radio signals lost in fog. And then someone noticed. There he is. A girl whispered. The kid? Yeah, he came back. Elliot walked through the door quietly. He carried the same canvas backpack faded along the seams. His shoes were the same brown pair with the cracked leather across the toe.

His coat was patched at the elbow with a careful hand, not storebought, but mended with pride. He made no eye contact. No attempt to speak. He went straight to the same seat, last row, right corner, near the heating vent. He opened his notebook, turned to a clean page, and wrote the date in the top right hand corner. September 6th. Lecture two. Properties of working fluids.

He clicked his pencil once, then twice, then a third time, just like last time. Some students stared, others smirked. “He’s back,” someone said again. “Probably hoping for a second scholarship,” another whispered. Elliot didn’t react. He focused on the board, even though nothing had been written yet.

His eyes moved as if already solving something invisible. Professor Richardson entered at 7:00 sharp. No greetings, no welcome, only the sound of her boots against the floor as she walked directly to the board. She lifted the marker and wrote three large words in black. Eisontropic compression process. Then she turned to the room.

All right, let’s see how many of you did the reading. She began with questions, fast ones, no time for hesitation. What’s the difference between an isoothermal and an adiabatic process? A hand went up, the student answered. She nodded but didn’t comment. What happens to temperature during an entropic compression? No hands this time. A few heads bent down, pretending to scroll through notes. Some looked away.

Then a voice from the back. It rises. The room turned. Richardson did not blink. Explain. Elliot sat up straighter. In an entropic process, he said, no heat is exchanged with the surroundings, so all work done on the gas goes into increasing internal energy. That means the temperature has to rise. Richardson paused. She looked at him a long moment, then turned to the board.

Correct. She said nothing more, but something in the room shifted. Not loud, not dramatic, just a quiet adjustment, like the wind had changed direction. For the rest of the lecture, Elliot wrote without pause. He copied every formula, every graph, every term she mentioned.

When she described the gas constant, he wrote it with four digits of precision. When she drew a pressure volume curve, he labeled the axes before she finished speaking. But the others noticed, too. By the third slide, whispers began again. Did he memorize that? He’s just paring stuff. Probably learned it working with his dad’s lawn mower.

One student, a tall boy named Dylan with perfectly ironed shirts and a voice always just a little too loud, leaned back in his seat. I give him a week, he muttered. A week before what? Someone asked. Before he breaks. This isn’t a place for charity stories. Elliot heard them, but he did not stop. That afternoon in the campus library, Elliot sat in the far corner.

He preferred the quiet space near the mechanical engineering shelves. The desk had a chip in one corner, and the chair tilted slightly to the left, but it had a good lamp, and that was enough. He opened a book titled Applied Thermodynamics and Internal Combustion. The pages were yellowed at the edges. Someone had underlined parts in blue ink years ago.

Elliot traced the outline of a heat exchange diagram with his pencil, then turned to his notebook and began copying it by hand, slowly, carefully, with margin notes written in small letters. Note, gamma increases as molecular complexity decreases. Watch temperature drift during piston delay. Try modeling with real gas values, not just ideal.

He worked until the sun dipped behind the far building. When the librarian flicked the lights twice, he stood, packed his bag, and walked out without saying a word. Tuesday’s lecture was harder. Richardson began discussing variable compression ratios and real gas behavior.

She introduced a graph comparing different fuels, gasoline, ethanol, methane, and their performance at high pressure. Compression is cheap power, she said. But past a point the gas stops cooperating. You get early ignition, heat loss, inefficiency. Know your limits. She tapped the diagram on the board. Someone tell me why helium performs poorly in this cycle again. Silence. Then Elliot spoke.

His voice was low but clear. Because of its high gamma value. The pressure rises too quickly during compression, causing premature ignition. Also, helium doesn’t absorb heat well, so you lose thermal buffering. Richardson raised an eyebrow. Textbook again. Elliot hesitated.

No, my dad told me he tried to fill a two-stroke with helium once to save weight. It blew the head gasket. The room laughed, but it wasn’t cruel this time. Even Richardson’s lips curved slightly, almost, but not quite, a smile. After class, a student named Toby caught up with Elliot in the hallway. “Hey,” he said. “That head gasket thing, was that real?” Elliot nodded.

My dad and I used to fix old engines in the backyard. He said, “If something breaks and you don’t know why, take it apart until you do.” Toby smiled. He was quiet, kinded, and carried a folder stuffed with scribbled diagrams. His father was a mechanic in Reno. They had more in common than either expected.

“Want to study together sometime?” Toby asked. Elliot looked surprised. Then he said, “Sure.” That evening, Dylan saw Elliot in the computer lab. He walked over, hands in his pockets. “Hey, genius,” he said with a half smile. You always talk like that or is it just for show? Elliot didn’t answer. Bet you can’t even drive a car yet, Dylan said. Elliot looked up.

My dad built an engine out of scrap that ran for 26 minutes before it overheated, he said. He said that was longer than any of his jobs ever lasted. He returned to his notebook. Dylan didn’t reply. He stood there for a second longer, then walked away. By the end of the week, something strange began to happen.

A few students started borrowing Elliot’s notes, quietly at first. Some asked him questions after class. Richardson began calling on him by name, not often, but without the bitterness of the first day. And in his seat at the back of the room, Elliot kept writing. He wrote not just what he was taught, but what he wanted to understand.

He copied questions to himself. Why do engines fail in high humidity? What if compression timing were asymmetrical? Could you build a piston head from recycled aluminum cans? He didn’t know if he belonged here, but he knew he would not stop. In the quiet of that Friday afternoon, while the other students left for the weekend, Elliot walked back into room B231.

He stood in front of the cutaway engine again. He placed his hand gently against the metal, still warm, still breathing, still broken, and he smiled because broken things could be studied. Broken things could be understood. He should not have known the answer, but he did. It was the third week of class.

The air in room B231 had begun to settle into its usual rhythm, part machine, part ritual. Students filed in, laptops clicked open. The low hum of fluorescent lights above cast a quiet, almost surgical brightness across the desks. But at the back of the room, Elliot Granger sat differently than before, still quiet, still unnoticed by most.

But something had changed. There was pencil dust on his fingers now, the kind that came from long nights writing equations over and over until the forms sank into the hand like music into the ear. There was also a second chair pulled beside him. Tobies. The two had begun studying together in the library, comparing notes, building small models from old bike parts Elliot brought from home.

They spoke in low voices, always technical, always curious. Not once had they spoken of pity or of charity, or of the laughter that still hung in the corners of the room, even when unspoken. That morning, Professor Richardson opened the lecture by drawing a rectangle on the board. She marked four corners labeled 1 to four and drew arrows through them in a loop.

The students recognized it at once. The autocycle, she said, the foundation of most internal combustion engines. Four steps. Ontropic compression, constant volume heat addition, ontropic expansion, and constant volume heat rejection. She wrote the word ideal in capital letters above the diagram.

Of course, she continued, real engines are never ideal. losses, friction, timing, heat transfer, all of it turns theory into noise. Then she paused, set down the marker, and asked a question. Can anyone explain why the auto cycle becomes unstable at high compression ratios beyond say a value of 10:1 particularly in air breathing engines without active cooling? It was a graduate level question.

Advanced thermodynamics, a subject usually reserved for thesis research and private labs. No one raised a hand. One student typed hurriedly. Another whispered to his neighbor, “Is she serious?” At the back of the room, Elliot lifted his head. He didn’t speak right away.

He closed his notebook, rested his hands on the desk, then slowly, as if testing his voice in the still air, he said, “Because of Knock.” Richardson turned to face him. The room followed. Elliot continued. When you raise the compression ratio too high, the temperature and pressure inside the cylinder increase beyond the auto ignition point of the fuel air mixture.

That causes the mixture to ignite too early before the piston reaches top dead center. A few students blinked. Richardson folded her arms. That’s the basic definition. Give me more. Elliot nodded. The pressure wave from early ignition travels faster than the flame front. It collides with the piston and chamber walls that creates shock waves, what we call knock.

It reduces efficiency, but more importantly, it can destroy the engine. He paused, then added softly, especially if the combustion chamber isn’t shaped to manage the heat zones. That’s why hemispherical heads are less prone to knock. Someone coughed. Someone else dropped their pen. Richardson stared at him a long moment. Then she spoke.

“And what’s the chemical basis of autoignition delay?” Elliot answered without looking at his notes. “Fuel molecules, especially hydrocarbons like octane, need a certain amount of activation energy to ignite. But when pressure and temperature are too high, the delay time between compression and ignition shortens, sometimes to less than a millisecond. If timing isn’t perfect, the engine fires too soon.

He looked down for a moment, as if searching for the right words. My dad used to say, “The engine decides when it wants to fire. Our job is just to give it the best chance to wait.” For a moment, no one said anything. Then Richardson turned back to the board. “Correct,” she said quietly, and she said, “No more.” After class, Dylan lingered near the front. He looked less confident than usual.

He approached Elliot, who was packing his notes into his bag. “You really knew all that?” Dylan asked. Elliot looked up. He didn’t answer right away. “My dad used to work on old delivery trucks,” he said finally. One of them knocked so bad we called it the hammer. He taught me to listen for pre-ignition even before it happened. You can smell it sometimes, like burned toast.

Dylan laughed, but not unkindly. That’s not in any textbook. Elliot shrugged. Not everything needs to be. That evening, Richardson sat alone in her office. The envelope Elliot had given her weeks ago, the one with the letter from admissions, was still in her drawer. She took it out again. Read it slowly.

It was signed by the department chair, stamped by the university, a special exception. One line had always stood out to her. This student has no formal record of early education, no test scores, but he has submitted independent technical documentation and demonstrated mechanical ability exceeding standard expectations. She reached for her pen, wrote one word in the margin, observer.

Then she crossed it out, learner. Then she crossed that out too. Finally, she wrote a third word and left it untouched. Engineer. Back in the dorms, Toby and Elliot sat on the floor of the common room, surrounded by notes and two empty soda cans. Elliot had cut one can in half and was using it to shape a model combustion chamber.

He showed Toby how to create a squish zone, a design that pushed the mixture toward the center of the cylinder during compression, reducing knock. This shape, Elliot said, keeps the flame front controlled, stops it from bouncing. Toby watched closely. Did your dad teach you this, too? Elliot shook his head. No, he taught me how to take things apart.

But putting them back together, I figured that out on my own. There was a pause. Toby smiled. Maybe you’ll figure us all out someday, too. Elliot didn’t answer, but for the first time that week, he smiled back. Later that night, when the campus had gone quiet and the wind rustled the leaves outside the old windows, Elliot sat alone by the cutaway engine in room B231. The lights were dim, the hallway silent.

He placed a hand on the engine’s frame, still cold, still still. He closed his eyes and listened, not to laughter, not to doubt, but to the shape of the machine, its rhythm, its breath, the way it might one day live again. If only someone took the time to understand it. And sometimes broken things like people could be fixed.

If you can fix it in 10 minutes, I will admit I was wrong. It was Thursday. The sky over Pasadena was pale and quiet, the kind of morning that made the red brick buildings of campus seem older, more permanent. In room B231, the students filed in with unusual focus. A rumor had started the night before that something unusual was going to happen, something involving the janitor’s kid.

They didn’t know the details, only that Professor Richardson had told the teaching assistant to prepare the research lab, and that Elliot Granger had been asked to stay after class. The news spread quickly, but quietly. Students carried it like a secret too precious to shout.

A challenge was coming, a test, not written on paper, and it would be public. The lecture that morning was shorter than usual. Richardson spoke quickly about energy losses in real engines, friction, vibration, incomplete combustion. Her voice was calm, but clipped. At the end, she closed her notes with a firm motion and looked up. “Follow me,” she said. No explanation, no hesitation.

The class followed her down the hall, past the graduate labs, past the row of framed portraits of Nobel winners. The air smelled faintly of oil and ozone. A place where things were taken apart, tested, sometimes broken. Room L12, the experimental engine lab. Richardson pushed open the door. Inside was a metal test stand holding a midsized engine prototype.

Its casing was matte silver, lined with temperature sensors, and wrapped in cables that led to a control panel nearby. It was the same machine Elliot had stood beside that first week, the one he had listened to, touched gently, the one that didn’t sound quite right. Now it waited like a creature holding its breath.

“Listen carefully,” said Richardson, turning to the class. “This engine designed for research on low temperature combustion has been under diagnosis for the past 4 months. It fails consistently during thermal stress testing. No one has solved it. Not our graduate team. Not even our visiting fellows. She paused.

Her gaze shifted to Elliot. And yet this student, this child claims to have found something. Elliot did not reply. He looked at the engine the way a clock maker looks at a time piece that once ticked in rhythm with quiet recognition. Not fear, Richardson continued. I am going to make a statement now in front of you all. If Mr.

Granger can diagnose and repair the failure within 10 minutes and bring this engine to stable operation, I will admit I was wrong. A silence fell over the room. Not just to him, she added, her voice harder now, but to all of you. She stepped back, crossed her arms. You may begin. Elliot moved without speaking.

He set down his bag, opened it carefully, and pulled out a pencil, a small notepad, and a pair of worn work gloves. He did not rush. First, he walked around the engine once. Slowly, listening again, not to its sound. It was not running, but to its shape, its posture. He brushed a finger along the intake valve, tapped the casing lightly with the side of his hand.

Then he looked toward the back where the oil pump connected to the main shaft. He crouched, placed his palm against the metal housing, closed his eyes. Dylan, standing near the back with folded arms, muttered, “What is he doing praying to it?” But no one laughed. This time, Toby stood with his hands clenched tight. After 2 minutes of silence, Elliot turned to Richardson.

What kind of oil was last used in this system? She raised an eyebrow. Sape 5W30 synthetic. And the pump housing, aluminum or mixed composite? Aluminum. Elliot nodded. When did the failure start? After a long load cycle under high ambient heat, the engine seized on cool down. He nodded again, then stood and walked to the panel.

“It’s cavitation,” he said quietly. “In the oil pump,” Richardson frowned. “Explain.” “When the engine reaches high operating temperature, the aluminum housing expands faster than the steel gears inside. That reduces the clearance between them. If the gap tightens too much, oil can’t flow properly. Pressure spikes. Microbubbles form and collapse.

That’s cavitation. It eats the surface from inside. He pointed to the casing. There’s pitting inside the pump. I can smell the metal wear. And the heat signature is slightly higher at cylinder 2 where the oil pressure drops first. He stood straight. The engine isn’t broken. It’s choking. A long silence.

Then Richardson asked quietly. And your solution? Elliot reached into his bag again. He pulled out a small gray tube. Malibdinum dissulfide. He said it’s a solid lubricant additive. It suspends in oil and forms a thin layer between moving parts even under extreme pressure. He held it up. normally used in race engines. My dad used it once on a snowb blower we rebuilt.

It ran for two winters after that. He walked to the pump access valve, opened it, and added a measured amount into the system. Then he stepped back. May I start it? Richardson gave a small nod. Elliot pressed the ignition switch. The engine turned once, twice, a sputter. Then it caught. A steady low hum filled the room.

Not perfect, but smooth. No knock, no stall, no spike in vibration. The control panel blinked green, stable. For a full 5 seconds, no one said a word. Then someone whispered, “He fixed it.” Another said, “That engine hasn’t run in months. Then someone, no one knows who, clapped once and then another and another until the room was full of hands and disbelief.

And Elliot, 12 years old, with grease on his gloves and a notebook full of dreams, just stood there, not smiling, not proud, just calm, as if the engine had said thank you. Richardson stepped forward. She looked at the engine, then at Elliot, and then she did something no one had ever seen her do in years of teaching. She extended her hand. “I was wrong,” she said, “Publicly, entirely.” Elliot hesitated, then shook it.

He didn’t touch the engine. He listened to it, and it spoke. The day after Elliot revived the research engine, room B231 felt different. The change wasn’t loud. It wasn’t a cheer or a handshake. It was quieter than that. Like the hush that follows a heavy snowfall when even the birds paused to notice something has shifted.

Students who once stared now glanced sideways with a hint of curiosity. Some nodded to him as they passed his desk. Small gestures without words. Dylan, once so loud, now arrived early and left without a sound. And Professor Richardson, though still firm, still razor sharp, had begun calling Elliot by name. Not Mr. Granger, just Elliot.

That morning, the engine, the same one that had failed for 4 months, was rolled into the lecture hall on a wheeled stand. It sat there silent and cold like a patient before surgery. Richardson looked at it then at the class. This, she said, was once our greatest frustration. Now it is our greatest question.

She turned to Elliot. Would you show them what you saw before you touched it, before the diagnosis? Elliot stood slowly. He walked toward the engine with his hands in his pockets. And for a long time he did nothing. The students watched, waiting for a gesture, for a tool to come out, for wires to be adjusted or parts removed. But Elliot didn’t reach for anything.

He stepped around the machine once, then twice. He leaned down and placed his ear near the lower housing. He didn’t flinch or react. Then he stood behind it where the intake met the manifold and simply stared. Not at the bolts, not at the wires, at the space between the parts, at how the machine held itself, its weight, its balance, its breath.

It was in some way like watching someone listen to a story only they could hear. After 5 minutes, Toby leaned toward Dylan. What’s he doing? Dylan shook his head. I think he’s thinking. Toby frowned. No, it’s more than that. He’s sensing something. And he was right. Elliot wasn’t just analyzing. He was remembering.

The sound of the second piston rattling ever so slightly before the oil warmed. The heat bloom near the lower cylinder. the faint scrape that had been dismissed as surface noise and the smell. It wasn’t obvious, not like burned rubber or leaking fuel, but it was there, faint, metallic, sharp, old steel under stress. He turned to Richardson.

When was the last time the oil was drained? 3 weeks ago, she replied. And the filter? Richardson glanced at the assistant. He hesitated. We didn’t change it, just topped it off. Elliot nodded. He walked back to the side panel and tapped gently along the casing. Then he spoke. Don’t start it. The class looked confused. Why not? asked a student near the front. Elliot looked up.

Because it’ll fail again. Richardson stepped closer. And why do you believe that? because it’s not just cavitation now. Elliot said that was the start. But the longer you run it with metal shavings in the oil, the more they circulate. They don’t always cause damage right away, but once they find a soft edge, they dig in. He pointed to the intake port.

I think there’s scoring on the sleeve of cylinder 2, just deep enough to catch heat, but not enough to show on a surface scan. Richardson raised her eyebrows. That’s a very specific theory. Elliot shrugged. I’ve seen it before. My dad rebuilt a mower engine three times before realizing the new oil pump was circulating grit from a torn filter.

The scratches didn’t show until we pulled the sleeve. Toby murmured. He remembers every engine. Richardson crossed her arms. “Then tell me,” she said. “What would you do if this were yours?” Elliot didn’t answer right away. He walked to the whiteboard and picked up a marker.

Slowly, carefully, he drew a simple diagram of the oil circulation system, labeling the flow from sump to filter to pump to heads. Then he drew a second version with what he believed had happened. He shaded a small area near the filter housing. This is where it starts, he said. Low-grade bypass. Small particles sneak through during startup.

It doesn’t show on the diagnostics because the wear is gradual, but it creates microabbrasions. He turned to the class. And eventually, you don’t have an engine. You have a grinder. The silence after that was not uncertainty. It was recognition. The way one craftsman listens to another, not because of their age, but because of the clarity of their vision. Finally, Richardson nodded.

Class dismissed. No explanation, no further questions, only one more glance at Elliot, who was now erasing the board quietly. That afternoon, Richardson sent an email to the department chair. It had no subject line, only one sentence. He does not guess. That night, as the campus settled under a soft breeze, Elliot sat by himself in the machine shop.

He had asked for permission to stay late, not to work on the research engine, but on something else. In front of him was a rusted lawn mower engine from the donation pile. He was disassembling it carefully, part by part, placing each piece on a clean cloth beside him. Toby came in carrying a small lamp. You’re still here? Elliot nodded. Toby sat down next to him.

“What are you building?” Elliot didn’t look up. “Nothing yet,” he said. “Right now, I’m just listening.” He lifted a worn piston, held it up to the light. Sometimes the damage is invisible until you feel it. A soft edge, a change in weight. You can’t measure it until it speaks to you. Toby didn’t answer. Instead, he watched, and as Elliot turned the piston slowly in his hand, it caught the light, just enough to reveal a fine groove running along its side. Not deep, but deep enough to tell a story.

Machines don’t lie, but they don’t speak loudly either. By the second month of the semester, Elliot Granger was no longer a curiosity. He had become something else. Not quite a classmate, not quite a legend, but a presence. Some students still whispered about how young he was, or how his coat cuffs were always frayed, or how he drank water from a recycled glass jar instead of a bottle, but they also copied his notes when he left them behind.

And when Richardson asked difficult questions, more than a few turned to see if Elliot would raise his hand. But Elliot never raised it first. He only spoke when no one else could. That week, Professor Richardson brought back the same engine, the one Elliot had revived. Now, she wanted more than revival. She wanted proof.

The cavitation theory holds, she said. But it’s not complete. We still don’t know why cylinder 2 loses power under extended load. She gestured toward the wheeled test stand. The engine sat in silence again as if waiting to be understood. “Find it,” she said. “Whoever solves it earns 5% added to their final grade.

” Gasps. Someone even whistled softly. But Elliot’s eyes stayed fixed on the machine. Not the reward, just the question. That afternoon, Elliot returned to the lab alone. He didn’t ask for help. He didn’t ask permission. He just stood beside the machine, laid his hands flat on its casing, and waited.

He closed his eyes. Then he began to smell. It wasn’t the sharpness of fuel or the sting of hot oil. It was something subtler, the faded scent of burned additive, like the kind used in cheap oil stabilizers, synthetic, but unstable under high heat. He had smelled it before on an old delivery truck his father fixed in the summer heat of Bakersfield.

It always came before failure. He leaned down. There was a dark stain just below the pump housing, barely the size of a coin. He reached into his coat, pulled out a folded cloth, and wiped it. Then he rubbed the cloth between his fingers. grit, not dust, metal. Later, when the students returned, Elliot stood quietly by the board.

No one had asked him to present, but he had written a diagram there anyway, the oil flow chart again, but this time he had marked a thin section between the pressure relief valve and the filter bypass line. This is the problem, Elliot said without turning. Richardson raised her head. Go on.

The filter is failing under heat, Elliot said. Not entirely, just enough. During high load, the pressure rises fast and the valve opens to protect the pump. That allows some oil to bypass filtration. He looked at the class, but the oil was already contaminated. It carries micro particles, mostly aluminum, from the pump housing. And those particles don’t settle, they swirl.

He walked to the engine and tapped the second cylinder gently. They land here. Toby stepped forward. But why only cylinder 2? Elliot looked at him. Because the oil flow favors it during startup. That line sits higher. It fills second but cools last. The particles follow the warmest path. Then he added almost like an afterthought. And this sleeve isn’t standard. It’s a field replacement. Cheaper alloy.

Richardson blinked. How do you know that? Elliot reached into his backpack. From it he pulled a small flashlight, old taped near the grip. He clicked it on, angled it under the housing, and pointed. There’s a scratch here. Perfectly straight. No circular scoring. That only happens during installation.

Someone forced it in, probably during a rebuild. The room went still. Richardson stepped forward and crouched beside him. She saw it. A hair thin groove invisible from above. “Good Lord,” she whispered. Dylan leaned toward the back row. He found it again. Toby whispered back. “He didn’t find it. He felt it.” That evening, Professor Richardson sat in her office long after sunset.

She pulled out a copy of the maintenance report for the engine. Rebuild date July 3rd. Technician D. Carlson, graduate assistant. Note, cylinder 2 replaced with stock part, alloy unverified. She closed the folder. Then, for the first time in many years, she began to write a letter.

Elliot, meanwhile, sat alone under the old tree behind the engineering lab. On his lap was a worn notebook. Inside it he had drawn two diagrams. One of the flawed oil flow and one of what he would build if he had the chance. A new engine where no flow bypassed truth and every part respected the others. He labeled it in block letters. The listening engine.

He closed the book and leaned back against the trunk, watching the stars. His hands smelled faintly of oil and aluminum and peace. It’s not broken. It’s misunderstood. The air inside room B231 was thick with waiting. On the long metal table stood the engine, silent again with its silver casing opened just enough to expose cylinder 2. The protective shield had been removed. Sensors disconnected.

Wires hung like veins pulled aside in surgery. Around the table, students stood like a silent jury, and Elliot Granger, small, steady, 12 years old, stood at the center, not like a boy about to prove himself, but like someone who had already listened, already known. Professor Richardson stood to one side, arms folded.

She had not interrupted once, not since yesterday, when Elliot had asked for one more night to confirm his suspicion. And now that silence was about to break. Elliot began by pointing to the exposed cylinder. This, he said, is not just a manufacturing flaw. He stepped to the whiteboard and drew a simple diagram. The oil pump, the connecting rods, the cylinder sleeve.

It’s a systems failure. A chain of small problems that only show up when they line up together, like gears. He turned. The problem is thermal expansion. He picked up a ruler and gently tapped the side of the engine. You used aluminum for the pump housing, he said. And steel for the gears inside it. That’s fine and under normal temperatures, but under load, aluminum expands faster than steel. He paused.

Almost twice as fast. On the board he wrote H aluminum is to 22 cars 10 to six de C a steel equal 12 bed 10 to 6 DY C. He turned back. When the temperature rises the aluminum expands the steel gears do not or not as much. That closes the gap between them. He walked around the engine slowly, tapping once more. The pump starts to bind. Pressure builds.

Cavitation begins. Microbubbles collapse near the surface, causing tiny impacts, like miniature explosions inside the oil. He looked at the class. It’s like the oil is boiling from inside. One student spoke up. But wouldn’t that show up in diagnostics? Elliot nodded. If you’re looking at pressure, yes, but not at wear.

Not at flow turbulence. The oil still moves, but it carries damage. He pointed to the valve. And then the filter fails. The bypass opens. Dirty oil flows through. Full of metal dust. It reaches the cylinder sleeve. He paused again. this sleeve. He reached into his backpack and pulled out a folded piece of paper, a print out from the lab’s material database. I checked the part number.

It’s not the same grade as the original. This one is lower density, slightly softer. Under heat and abrasion, it wears faster. He stepped back, which means the problem isn’t just the oil or the pump or the sleeve. He looked straight at Richardson. It’s the space between them. Silence. Then slowly, Richardson walked forward.

She looked down at the sleeve, at the fine line Elliot had shown her, at the uneven ridge inside the cylinder wall, at the shimmer of metal dust on the edge of the oil chamber. She didn’t speak for a long moment. Then she said almost quietly, “No one even thought to measure the thermal mismatch.” Elliot said nothing. He didn’t need to.

A few students began murmuring. Not disbelief, not sarcasm, but awe. One whispered, “That’s not just engineering. That’s poetry.” Another said, “He thinks like the machine feels.” Dylan, who once mocked Elliot’s shoes, was now the first to ask the next question. How would you fix it? Elliot answered simply, “Replace the sleeve with a higher grade alloy, something heat treated.

Recut the gear teeth in the pump with a wider tolerance, 1/10enth of a millimeter more, and change the oil blend.” Richardson raised her eyebrows. Change it to what? Elliot opened his notebook. He flipped to a handdrawn table of viscosities and additives. “This one,” he said, pointing. “Synthetic blend with malibdinum and esters.

It holds viscosity better when heat spikes.” He looked back at her. My dad used it on an old grain truck. It stopped knocking after 3 days. Richardson didn’t speak. She simply nodded. And for the first time, not with challenge, not with caution, she said, “Elliot, would you lead the repair?” The class went completely silent. Elliot blinked. “Yes, ma’am.

” That evening, long after the others had gone, Elliot remained in the lab. He worked slowly, carefully. He wore gloves, but still wiped his hands between steps. Each bolt placed aside with care. Each thread checked twice. The room filled not with noise, but with the soft rhythm of tools and breath. Richardson sat in the corner watching.

She said nothing until he finished reassembling the pump housing. Then she asked, “How did you learn to listen like that?” Elliot looked up. My dad taught me to fix things with no manuals. So, I had to learn from the sound, from the heat, from the way the metal smells when it starts to give. She tilted her head.

And people, Elliot paused. People are harder. Before she left, she looked once more at the engine. It’s a good diagnosis, she said. Elliot didn’t respond right away. Then he said softly, “It’s not broken. It was just asking for help.” He didn’t restart the engine. He healed it.

The room was still, not with tension, not anymore, but with attention, a kind of stillness reserved for the final moment in a long symphony, when everyone knows the next note could change everything. The research engine, now reassembled, stood on the metal stand like a patient waking from surgery. The new sleeve was in place.

The oil had been drained, filtered, and replaced with the exact blend Elliot had chosen. The pump’s gear clearance had been adjusted, carefully recut by hand, 1/10enth of a millimeter wider, but still it had not been started. Not yet. Elliot stood beside it. He was not in a rush. In his hands, he held a small gray bottle. It was plain with no label, but a black marker line across the side.

Malibdinum dissulfied solid lubricant in liquid suspension. He had brought it from home. “Where did you get that?” Dylan asked quietly. Elliot didn’t look up. “My dad salvaged it from an old drag racing shop. said they used to call it black honey. He turned the cap slowly, no splash, no show, just a steady pour, 10 ml, no more, into the pump’s access port.

He wiped the cap clean, tightened it, and set the bottle aside. Then he placed one hand on the top of the casing, closed his eyes for a moment, and pressed the ignition switch. The engine turned once, twice. A faint sputter. Then a deep smooth hum filled the room. Not loud, not aggressive, just right, balanced, like a stone finally finding its place in the river. On the control panel, the indicators turned green.

vibration normal heat stable oil pressure perfect. The graphs began drawing smooth curves on the screen. Torque response, fuel flow, cylinder temp, and the class for just a moment forgot how to breathe. Then it came the sound, a gasp, a rising cheer, applause. Someone let out a shout. It’s alive.

And through it all, Elliot simply stood there. He didn’t smile. He didn’t bow. He just nodded as if the engine had spoken back. And he had heard it. Professor Richardson stepped forward. She didn’t touch the engine. She didn’t need to. She looked at the readings, then at the class, then finally at Elliot. “What do you call that?” she asked. Elliot thought for a moment.

Respect, he said. The room fell silent again, but this time it was reverent, not the silence of disbelief, the silence of being present for something true. Later, after the students had left, Richardson remained. Elliot stood beside the engine, wiping his tools one by one.

She asked quietly, “How did you know that would work?” Elliot shrugged. I didn’t, he said. I listened. I learned. I watched what it didn’t like. She tilted her head. That’s not standard methodology. No, he said, “But machines have moods. They remember how you treat them.” Richardson smiled, a real smile, for the first time. “You’re not just an engineer,” she said. You’re a mechanic of empathy.

Elliot looked at her. I just try to make things feel safe enough to work again. That evening, Richardson sent a short memo to the faculty board. It read, “Recommend Elliot Granger for long-term audit status in the department, access to labs, mentorship, and independent projects. He has already taught us something we forgot.

Machines are only as broken as our willingness to understand them. Toby caught up with Elliot outside the lab. The sun was setting, turning the sidewalks gold. “I can’t believe it,” Toby said. “You fixed it in under a minute.” Elliot shook his head. “I didn’t fix it in a minute,” he said. He looked up at the sky.

“It just took 30 seconds to show what I’d been feeling for weeks.” Toby smiled. “Feels like magic.” Elliot smiled too. Not magic, he said. Just patience. You promised in front of everyone. I intend to keep that promise in front of everyone. The next lecture was different. Not because of the content.

Richardson still taught with the same clipped voice, the same precision, the same refusal to repeat herself, but something in the room had changed. Respect now had a shape. It sat in the back row as always, a 12-year-old boy with patched elbows and engine grease in the creases of his knuckles. Elliot no longer had to defend his place. No one questioned it anymore. They had seen the engine run.

They had felt it. On the whiteboard that morning, Richardson wrote in capital letters, “Genius may be rare, but humility is rarer.” Then she turned to the class. “I have a correction to make,” she said. “On the first day of this course, I said something. I implied this class wasn’t for janitors kids.” She paused. Let the memory sink in.

I was wrong. Not a whisper stirred in the room. She nodded toward Elliot. I made a promise that if this student could repair an engine that had defeated graduate researchers for months, I would acknowledge it publicly. She turned back to the class. This is me doing that. She stepped aside and gestured toward the front. Mr. Elliot Granger is now an official student researcher in this department.

He will assist in engine diagnostics, lab instruction, and technical documentation. I have also filed for tuition exemption should he pursue formal admission. The class blinked. Then applause began. Not thunderous, not staged, just honest. And Elliot, stunned, did something rare. He smiled. After class, Richardson stopped him outside.

“There’s one more promise I need to keep,” she said. Elliot tilted his head. She handed him a folded sheet of paper. An official invitation. Guest lecturer. Introduction to mechanical systems. Name: Thomas Granger. Topic: What a janitor knows that an engineer sometimes forgets. Elliot froze. “My father?” he asked softly.

She nodded. “He taught you more than most students ever learn in 4 years. That kind of experience deserves the front of the room, not the back hallway.” Elliot held the paper like something sacred. “He hasn’t spoken in front of a crowd in 20 years,” he whispered. “Then it’s time,” Richardson said.

Some truths are too important to stay silent. The following Tuesday, room B231 was filled to capacity. Students lined the walls, notebooks in hand. Several professors stood at the back. Even the janitorial staff, many of whom had never set foot in a lecture hall, came and sat near the doors. The atmosphere was reverent.

At the front of the room stood a man in work boots and a pressed shirt. His hands were rough. His voice was quiet. But when Thomas Granger spoke, the room leaned in. He didn’t lecture. He told stories about engines that coughed in winter and machines that sang when treated with care. About how he taught his son to listen to metal like a mechanic listens to weather.

About mistakes he had made, and how each one taught more than success ever could. He picked up a wrench from the demonstration table and held it high. This, he said, is not just a tool. It’s a way of thinking. You don’t hit with it. You feel with it. He looked at the crowd. And if you ever meet someone who listens to a broken machine before blaming it, that person is already an engineer.

When he finished, no one moved for a long time. Then came the applause. deep and lasting, not because he had used equations, but because he had spoken truth, raw, simple, necessary. Afterward, Elliot helped his father gather the tools. He looked up at him. You weren’t nervous. Thomas smiled. I was. But I remembered something.

What? That you believed in me before anyone believed in you. Elliot looked down. He was quiet for a moment. Then he said, “I want to teach someday.” Thomas placed a hand on his shoulder. You already have. That evening, back in the lab, Elliot found a small envelope taped to his workbench. Inside was a key and a note. Lab 4a is yours now for your own work.

Miru Richardson. He sat down on the stool, stared at the key in his palm. Then slowly, carefully, he opened his notebook. On a blank page, he wrote three words. Next engine, mine. Not every student needs a desk. Some just need a chance. By late November, Caltech’s sky had taken on that winter softness.

Not cold enough for snow, but just enough to turn sunlight into something gentle. Room B231 now opened 10 minutes early. Not because the schedule had changed, but because students wanted more time to talk before lecture. Not about grades, not about lab reports, but about engines, about sound, about feel, about the quietest student in the room. Elliot Granger no longer sat in the back.

His seat, still humble, still near the heater, had become a center point. Students now passed their notebooks to him after class, asking for feedback. Not for correction, but for sense. They no longer asked what was right. They asked, “What feels wrong to you?” And when Elliot answered, he didn’t speak in formulas.

He spoke in stories, in smells, in sounds, in moments when metal gives a little more than it should. and they listened. Professor Richardson had changed, too. Her lectures, once a wall of concepts and precision, had opened. She still taught with rigor, still expected excellence.

But now, before introducing a new system or equation, she began with a question. What might this machine not be telling us? She called it the Granger method. Not inest, in honor. That final week before winter break, Richardson invited students to present independent studies. Most built models. One student tried simulating heat loss in small combustion chambers.

Another presented a prototype piston using recycled alloys. But when it came time for Elliot, he didn’t bring slides. He brought something else. A small engine, handbuilt. No label, no brand. Every piece had been machined or repurposed by Elliot alone. The casing was polished aluminum. The piston head bore a tiny scratch, sealed over with silver epoxy.

Intentional, a reminder of imperfection. He placed it on the front desk. “This is not a new engine,” he said. “It’s a patient one.” He turned the crank. It started on the first try. The room filled with a soft, steady hum, not loud, but warm. Most engines, Elliot said, are designed to push. He looked around the room.

This one was built to wait. When the class ended, Richardson stood beside him. She looked down at the humming model. “What did you name it?” she asked. Elliot glanced sideways. I didn’t. Why not? Because it’s not done learning. That evening, Elliot walked home with his father. They passed the science building, the old gym, and the janitor’s supply room.

Thomas Granger looked down at his son. “You changed this place,” he said. Elliot shook his head. “No, I just made them remember what machines are.” “And what’s that?” Elliot thought for a while. Then he said, “Not puzzles, not problems, just things trying to work if we’d let them.” His father smiled and people. Elliot looked at the sidewalk, then at the stars. They’re the same.

The next morning, Elliot visited lab 4A, his lab now. He opened the door, turned on the light. The walls were bare. the bench clean. But in the center of the table sat a small wooden plaque, a gift. No name on it, just six words carved by hand. Listen first. Speak if needed. Build. Years later, people would ask where Elliot Granger went to school. Some said Caltech. Some said the library.

Others said his father’s garage. But the students of that one class would always answer the same way. We didn’t teach him. He taught us how to hear again. Thank you for staying long enough to hear the story of Elliot Granger. A boy who didn’t walk into greatness through the front door, but through the back halls of a school his father cleaned every night. He didn’t come from a laboratory.

He came from a workshop, from the clatter of broken engines, from the quiet advice of a father who never stood behind a lectern, but knew the sound of failing metal like a heartbeat. If you’ve ever sat in the back of a room, ever been judged by your worn out shoes or your silence, or been told you didn’t belong, then maybe, just maybe, Elliot was a younger version of you coming back one more time to be heard.