At 06:30 on March 1st, 1943, Major Ed Lner stood on the rain soaked coral runway at Port Moresby, watching his B25 Mitchell bomber crews prepare for a mission that higher command had already called impossible. 31 years old, 72 combat missions, zero ships sunk. The Japanese had dispatched eight troop transports and eight destroyers from Rabalo, carrying nearly 7,000 soldiers to reinforce their garrison at Lei. American intelligence had intercepted the convoys departure. Every transport that reached Lei meant another division the Allies would have to dig out of the jungle with blood.

Lner’s problem was simple. Traditional bombing from 10,000 feet gave ships too much time to maneuver. Japanese captains watched American bombers climb to altitude, calculated the bomb trajectory, and turned their vessels away from the splash zones. Fifth Air Force B7s had been trying to hit Japanese convoys for 8 months. Hit rate 3%. Most bombs exploded harmlessly in empty ocean while the ship steamed on. The mathematics were brutal. A,000lb bomb dropped from altitude took 37 seconds to hit water.

In those 37 seconds, a destroyer traveling at 30 knots covered 380 yd, more than three football fields. The bombader aimed at where the ship was. The bomb hit where the ship used to be. Lner had watched it happen mission after mission. Bombers would come back with perfect bombing photographs showing tight patterns around the ships. around them, never on them. Crews reported direct hits that turned out to be near misses. The Japanese kept sailing. American bomber losses kept climbing.

His squadron had lost four aircraft in the past month trying to hit convoys. 40 men. The Japanese shot down high alitude bombers with methodical precision. Their gunners had time to track the approach, calculate the lead, and bracket the formation with flack. By the time bombs fell, half the squadron was burning. General George Kenny, commanding Fifth Air Force, had proposed something that sounded insane to every pilot who heard it. Skip the bomb across the water like a flat stone.

Fly in at 50 ft. Release the bomb 300 yd out with a 5-second delay fuse. Let momentum carry it into the ship’s hull. The bomb would skip once, maybe twice, then detonate on contact or just under the water line. The theorists said it would work. The pilots said it was suicide. Flying a twin engine bomber at 50 ft above ocean swells straight at a ship bristling with anti-aircraft guns violated every survival instinct LNER had developed. Japanese destroyers carried 127 millimeter main guns, 25mm machine cannons, and dozens of lighter weapons.

All of them could track a bomber at that altitude. One solid hit to the engine, and the B-25 would cartwheel into the sea before the crew could blink. Higher command had banned the tactic twice. Too dangerous, too experimental, unproven. Lner’s request to practice skip bombing had been denied in December and again in January. The official response called it reckless disregard for equipment and personnel. Air crews needed to focus on proven highaltitude tactics. But high alitude tactics weren’t sinking ships.

If you want to see how Lner skip bombing experiment turned out, please hit that like button. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Pacific War. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Lner. Lner walked to the operations tent and spread reconnaissance photographs across the planning table. The Japanese convoy had been spotted at dawn, steaming southeast through the Bismar Sea. Eight fat transports in two columns, destroyers screening the flanks. Every ship packed with soldiers, artillery, ammunition.

If those transports reached Lei, the war in New Guinea would grind on for another year. He had an idea that would either vindicate Kenny’s faith in lowaltitude attacks or get 60 American air crews killed before lunch. The convoy would pass within striking range at 0900. 3 hours to prepare, 3 hours to teach his pilots to fly like they’d never flown before. Lner called his squadron leaders to the tent and laid out the plan they’d been forbidden to practice.

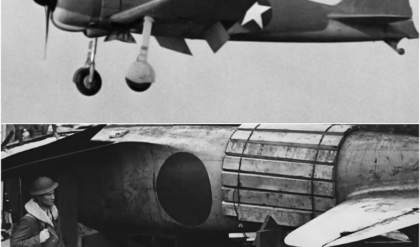

The B-25 Mitchell wasn’t designed for what Lner was asking. The bomber had been built to hit targets from medium altitude with a level bombing approach. Its twin right cyclone engines could push it to 300 mph in level flight. But that speed meant nothing if Japanese gunners had 30 seconds to track the approach. Kenny’s modification changed everything. Fifth Air Force mechanics had ripped out the bombardier position in the nose and installed eight 50 caliber machine guns pointing forward.

Four in the nose, four in blisters on the fuselage sides. The B-25 had become a flying gun platform that could put 200 rounds per second into a target. The theory was simple. Suppress the ship’s anti-aircraft guns with machine gun fire during the approach. Give the gunners a reason to duck. make them choose between returning fire and surviving. Lner had watched mechanics bolt the guns onto his aircraft three weeks earlier. The modification added 1,200 lb. It shifted the center of gravity forward.

It turned his bomber into something between an attack aircraft and a maritime strike fighter. Something that had never existed before. The practice runs had been conducted in secret. Kenny had found a wreck called the Pruth, a 4,700 ton steamer that had run a ground on Nater Reef near Port Moresby in 1924. The Rusting Hulk sat half submerged, a perfect target. Lner’s crews flew practice runs at dawn and dusk when the light was bad and observers were few.

They learned to skim the wavetops at 270 mph. They learned to time the bomb release. They learned what happened when you got it wrong. Lieutenant Jake Faucet had gotten it wrong on February 16th. He’d come in too high, 70 ft instead of 50. The bomb had skipped twice, cleared the proof entirely, and detonated 300 yd beyond the wreck. Faucet’s bombardier, Sergeant Mike Russo, had recalculated. Lower, faster, closer release point. The next run, Faucet came in at 45 ft.

The bomb skipped once and slammed into the proof’s hull just below the water line. Right where a ship’s magazine would be, right where one bomb could detonate a thousand tons of ammunition and blow a destroyer in half. But the proof wasn’t shooting back. Lner spread the reconnaissance photos across the briefing table and pointed to the lead transport, 800 ft long, displacing 10,000 tons, capable of carrying 1,500 troops, the convoy’s flagship. Every officer in the tent knew what was at stake.

Japanese reinforcements had turned Buna into a six-month nightmare that had cost 5,000 Allied casualties. Lei would be worse if those transports unloaded. The mathematics of skip bombing required precision most bomber crews had never attempted. Approach altitude 50 ft above the water. Approach speed 270 mph. Release point 300 yd from target. Bomb trajectory angle 8°. Delay fuse 5 seconds. Miss any one variable and the bomb would either skip over the ship, detonate short, or hit the water at the wrong angle and sink without detonating.

Lner assigned each pilot a specific target. Transport one through transport 8. Destroyers as secondary targets if the transports were already burning. No bomber would attack the same ship twice. Maximum efficiency, maximum destruction. One pass, one bomb, one chance. The crews filed out to their aircraft at 0700. 54 men in nine B-25s. Behind them, 13 bow fighters from the Royal Australian Air Force would strafe the convoy first, suppressing anti-aircraft fire. Above them, 16 B7 flying fortresses would bomb from altitude, forcing the Japanese ships to maneuver and breaking up their formations.

The P38 Lightning fighters would keep Japanese Zeros busy at high altitude, but the killing blow would come from Lner’s nine bombers at 50 ft. He climbed into his aircraft at 0715. His co-pilot, Lieutenant Tom Benz, was already running through the pre-flight checklist. The bombader, Staff Sergeant Carl Walls, was checking the bomb release mechanism for the fourth time. Nobody spoke. The entire crew had flown together for 9 months. They knew what a 50-ft approach meant. They knew the odds.

Lner started the port engine, then the starboard. The right cyclones caught and settled into their familiar roar. Around him, eight other B-25s were winding up. The formation would take off in flights of three. Lner’s flight first. Stay low over the water the entire way. Japanese radar couldn’t track aircraft below 100 ft. Surprise was the only advantage they had. At 0745, Lner released the brakes and began his takeoff roll. By 09:30, he would know if Kenny’s theory worked or if he just led his entire squadron into a slaughter.

The flight to the Bismar Sea took 90 minutes. Lner kept his formation at 30 ft above the ocean, low enough that spray from the wave tops occasionally spattered his windscreen. The B-25s flew in a loose V formation. Each aircraft separated by 200 yd. Close enough to maintain visual contact. Far enough that one burst of flack couldn’t take down two bombers. Radio silence. The Japanese monitored every frequency. One transmission and the convoy would know American bombers were inbound.

Surprise was worth more than coordination. Lner checked his watch. 08:30. The convoy should be 60 mi northeast, steaming at 12 knots toward the VTZ straight. Right on schedule, according to the morning reconnaissance report, the ocean below was empty. No white caps, no Japanese patrol boats, just endless blue water stretching to the horizon in every direction. Flying this low, Lner couldn’t see more than 5 m. The convoy could be anywhere. His navigation had to be perfect. 5° off course and they’d missed the target entirely.

Come up on the convoy from the wrong angle and the destroyers would have time to bring their main guns to bear. At 0852, Lner spotted smoke on the horizon. Black diesel exhaust from 16 ships steaming in formation. He keyed his throat microphone once. Click the signal to Titan formation. His wingmen acknowledged with single clicks. Radio discipline holding. The convoy took shape as they closed. two columns of transports, four ships per column. The destroyers formed a protective screen two miles ahead and on both flanks.

Lner counted gun positions on the nearest destroyer. Six main turrets, dozens of smaller weapons. Every gun would be tracking his approach once they broke the horizon. At 0857, the bow fighters went in. Lner watched from 3 mi out as 13 Australian aircraft dove on the convoy from the northeast. Their 20mm cannons rad the destroyer decks. Tracers arked across the water. The Japanese anti-aircraft guns swung toward the new threat. Exactly as planned. The bow fighters weren’t there to sink ships.

They were there to make the gunners look the wrong direction. 30 seconds later, the B7s arrived at 10,000 ft. Lner saw the Bombay doors open. Bombs tumbled toward the convoy. The Japanese ships began evasive maneuvers, turning hard to port and starboard. Columns broke apart. Spacing increased. The destroyers accelerated to flank speed, white water foaming at their sterns. Confusion. Perfect. Lner pulled back on the throttles and descended to 40 ft. His air speed dropped to 260 mph. Walls, his bombardier, was calling out distances.

4,000 yd 3,800 3,600. Each ship in the convoy was now clearly visible. Lner picked his target, the second transport in the port column, 700 ft long, sitting low in the water, fully loaded. His bomb would hit amid ships, right where the troop compartments were packed with soldiers. The destroyer on the left flank spotted them. Lner saw muzzle flashes. The first shells arked toward his formation. Too high. The Japanese gunners were used to tracking bombers at altitude. They hadn’t adjusted for a 50-ft approach yet.

At 2,000 yd, Lner opened fire. All eight caliber machine guns hammered. Tracers walked across the transport’s superructure. Glass shattered. Metal sparked. Men on deck dropped or dove for cover. The suppression was working. The anti-aircraft crews couldn’t shoot back while half-in bullets were tearing through their positions at 800 rounds per minute. 1,200 yd. Lner’s wingmen were spreading out. Each bomber lining up on its assigned target. The formation was fragmenting by design. Nine bombers attacking nine ships simultaneously. No time for the defenders to shift fire.

No time to coordinate a response. 800 yd. The destroyer’s main guns fired again. This time, the shells bracketed LNER’s flight. Left, right. Close enough to rock the aircraft with concussion. Shrapnel pinged off the fuselage. Ben, the co-pilot, called out, damage. Port engine oil pressure dropping. Still in the green. 600 yd. The transport filled Lner’s windcreen. He could see individual soldiers on deck scrambling for cover. could see the bridge windows, could see the ship’s gun crews swinging their weapons toward him.

Every instinct screamed to pull up, to climb, to get away from the wall of steel rushing toward him at a combined closing speed of 300 mph. 400 yd. Waltz’s voice cut through the engine roar. Bomb armed, ready for release. 300 yd. Lner pressed the bomb release. He felt the aircraft lurch upward as 1,000 lbs dropped free. The bomb tumbled forward, carried by momentum. It hit the water nose first, skipped once like a flat stone, and arrowed toward the transport’s hull.

Lner pulled hard on the control yolk, and climbed behind him. The 5-second fuse was counting down. The bomb detonated at the water line. Lner didn’t see the explosion. He was climbing hard, his vision filled with sky, but he felt it. The shock wave hit his aircraft like a physical blow, lifting the tail and throwing the B-25 sideways. Ben’s fought the controls. The altimeter spun through 100 ft, 200, 300. Lner risked a glance back. The transport was splitting open.

A column of fire and black smoke erupted from amid ships. The hole buckled. Metal shrieked. Secondary explosions rippled through the superructure as ammunition stores cooked off. The ship listed to port, already taking water through the massive hole torn in its side. Soldiers were jumping overboard. Dozens of them, tiny figures abandoning a dying ship. One bomb 15 seconds from release to catastrophic damage. The skip bombing worked. To Lner’s right, Lieutenant Jake Faucett’s bomber was pulling up from its own attack run.

Another transport was burning, flames climbing its forward mast. To the left, Captain Bill Hayes had just released on a destroyer. The bomb skipped twice and hit below the aft turret. The destroyer’s stern lifted out of the water from the internal explosion. When it crashed back down, the entire rear third of the ship was missing. The destroyer began settling by the stern, sinking fast. Four targets hit in the first 90 seconds. The Japanese convoy was in chaos, but the defenders were adapting.

A destroyer on the far flank had turned to face the bombers. Its main guns fired in rapid succession. The shells walked across the water toward Lieutenant Tom Mitchell’s B25. The first shell missed by 50 yards, the second by 20, the third hit. Mitchell’s aircraft disintegrated. The bomb under the fuselage detonated on impact. The explosion vaporized the bomber instantly. No parachutes, no survivors. Five men gone between one heartbeat and the next. Lner watched the debris scatter across the water.

No time to process it. No time to mourn. The attack was still happening. The remaining B-25s pressed their attacks. Lieutenant Carl Johnson lined up on the lead transport, the convoy flagship. His approach was textbook. 50 ft, 270 mph, machine guns blazing. The Japanese crew was firing back with everything they had. 20mm cannons, heavy machine guns, even rifles. The air between Johnson’s bomber and the transport was solid with tracers. Johnson’s bomb release was perfect. The weapon skipped once and punched through the transport’s hall just forward of the bridge.

The delay fuse gave it time to penetrate deep into the ship before detonating. The explosion tore through three decks. Fire erupted from the cargo holds. Lner knew what was in those holds. Ammunition, artillery shells, fuel drums. The transport became an inferno. Men were burning on deck, jumping into the sea, trailing smoke. Lieutenant Paul Warren’s bomber took hits during its approach. A Japanese gunner on one of the destroyers had finally adjusted for the lowaltitude attack. 20 mm shells ripped through Warren’s port wing.

Fuel streamed from the punctured tank. Warren held his course. 300 yd. 200. At 150 yards, he released. The bomb skipped and struck the transport below the water line. Warren banked hard right, trailing fire. His co-pilot, Lieutenant Dave Miller, was already activating the fire suppression system. The flames died. The bomber was still flying barely. Six transports burning or sinking. Two destroyers damaged, one B-25 lost. The attack had lasted four minutes. The second wave was coming in. Nine more B25s from the 90th Bomb Squadron, led by Major Ralph Chel.

They’d watched Lner’s attack from 5 miles out. They knew the tactic worked. They knew the cost. Chel’s formation spread out, each bomber selecting a target from the ships still afloat. The Japanese were ready this time. Every gun in the convoy was tracking low. The destroyers had formed a defensive line, their main batteries firing in coordinated volleys. The ocean erupted with shell splashes. The barrage was intense, deadly, calculated. The Japanese had learned from the first attack they would make the Americans pay for the second.

Chel’s bomber came in from the east, directly into the sun. smart. The Japanese gunners were half blind, firing at shadows. His bomb hit a transport that was already listing. The explosion accelerated the sinking. The ship rolled onto its side and went under in less than 2 minutes. 1,200 soldiers went down with it. Lieutenant Harold Jensen wasn’t as lucky. His approach angle was wrong. Too shallow, too fast. His bomb skipped three times, cleared the target destroyer entirely, and detonated harmlessly beyond the convoy.

Jensen pulled up and circled for another run. The Japanese destroyer he’d missed tracked him the entire turn. When Jensen came around for his second pass, the destroyer was waiting. The first shell took off his port engine. The second hit the cockpit. Jensen’s B25 rolled inverted and crashed into the sea at 300 mph. No explosion, just impact. The ocean swallowed the aircraft and kept moving. Two bombers down, seven transports sinking, three destroyers crippled. The battle had been raging for 8 minutes, and Lner realized with cold clarity that the Japanese still had 60 Zero fighters somewhere above the clouds.

The Zeros appeared at 09:15, 18 of them diving from 12,000 ft. Lner saw them through scattered clouds, silver shapes dropping toward the bombers like hawks on field mice. The P38 Lightnings were supposed to keep them occupied. Something had gone wrong. Either the Lightnings were outnumbered or the Japanese had committed a second fighter group nobody knew about. Lner’s B25 was vulnerable. Low on fuel, low on ammunition. The machine guns in his nose had maybe 200 rounds left. Not enough for a sustained dog fight.

Not enough to hold off a determined zero pilot who’d learned to respect American bombers the hard way. He pushed the throttles forward and dove to wavetop height. 20 ft 15. The propellers were churning salt spray. The zeros split into two groups. Half stayed high to engage the P38s. The other nine went after the bombers. They came in fast, 400 mph, firing their 20 mm cannons from 1,000 yd out. Lner saw tracers arc past his canopy. Too close.

He jinked left, then right, making himself a difficult target. Behind him, Staff Sergeant Tommy Blake was in the dorsal gun turret, firing short, controlled bursts at the nearest zero. The Japanese fighter broke off. Not damaged, just cautious. Lieutenant Warren’s damaged bomber wasn’t so lucky. Azero latched onto his tail and stayed there. Warren tried every evasive maneuver he knew. Climbs, dives, hard banking turns that stressed his damaged wing. Nothing worked. The zero pilot was good. Patient, he waited until Warren ran out of air speed in a climbing turn, then fired a two-cond burst.

Warren’s starboard engine exploded. The bomber nosed over and went into the ocean. Lner saw three parachutes, three out of five. Better than nothing. The Zeros pressed their attack for 6 minutes. Then abruptly, they broke off and climbed. Lner couldn’t figure it out until he saw why. The B7s were coming back for a second pass at 10,000 ft. The Zeros had to choose. Attack the bombers below or defend the convoy from above. They chose above. The heavy bombers were the bigger threat to what remained of the convoy.

Lner used the reprieve to assess damage. His port engine was running rough. Oil pressure fluctuating. Fuel gauge showing 60%. Enough to make it back to Port Moresby. Maybe. He looked back at the convoy. Eight transports had been hit. Seven were sinking or already gone. The eighth was burning but still afloat. Trying to make way toward the New Britain coast. All four destroyers on the screening line were damaged. Two were dead in the water. The other two were circling the burning transports trying to pick up survivors.

The battle of the Bismar Sea wasn’t over. It was 0921. The initial attack had lasted 11 minutes, but the killing would continue for three more days. American bombers would return every 6 hours. PT boats would hunt survivors in lifeboats. The Japanese had committed 7,000 troops to this convoy. Fewer than,200 would make it to lay. The rest would drown, burn, or die of exposure in the tropical sun. Lner set course for home. His formation was scattered across 30 mi of ocean.

Four bombers were confirmed lost. 20 men dead or missing. But the mission had worked. Skip bombing had proven itself in the most brutal way possible. The technique would be refined, standardized, taught to every bomber squadron in the Pacific. Within 6 months, Japanese commanders would abandon any attempt to move large convoys within range of Allied air power. The supply line to their forward bases would strangle. the war would turn. But LNER didn’t know that yet. He only knew his fuel gauge was dropping, his engine was failing, and Port Moresby was 90 minutes away.

He ordered his crew to dump everything not essential. Ammunition, guns, they couldn’t use, tools, spare parts, anything to reduce weight. The B25 was struggling to maintain altitude with one engine running rough. At 010, Ben spotted land. the southern coast of New Guinea. They were on course barely. The port engine was shaking now. Oil streaming from a crack in the housing. Temperature gauge climbing into the red. 5 more minutes and it would seize completely. Lner feathered the port propeller and transferred all power to the starboard engine.

The bomber slowed to 180 mph, just above stall speed, just enough to stay airborne. The coast was getting closer. 40 m 30 20. The engine held. Lner landed at Port Moresby at 1117. The runway was lined with ground crews, mechanics, intelligence officers. Word had spread. The convoy had been hit hard. Nobody knew how hard. Lner cut the engines and sat in the cockpit for 30 seconds, hands still gripping the control yolk. Then was silent beside him. Neither man moved.

They’d been flying for 3 hours and 42 minutes. It felt like 3 days. The debrief lasted 2 hours. Lner and his surviving pilots sat in the operations tent while intelligence officers asked the same questions in different ways. How many ships hit? How many sinking? How many bombs released? How many aircraft lost? The officers were building a picture from fragments. Nine pilots had attacked. Five had returned. Mitchell gone. Jensen gone. Warren in the water. His crew picked up by a Catalina flying boat.

Two men wounded. The reconnaissance photos arrived at 1300 hours. An Australian Bowford had photographed the convoy from 15,000 ft at noon. The images told the story Learner’s crew couldn’t. Eight transports. Seven confirmed sunk or sinking. The eighth beed on the New Britain coast. Burning. Four destroyers, two sunk, two severely damaged, and withdrawing toward Rabbal. Total time from first attack to last chip down, 3 hours. General Kenny arrived at Port Moresby at 1600 hours. He walked directly to the operations tent and spread the reconnaissance photos across the briefing table.

He didn’t congratulate anyone, didn’t shake hands. He pointed at the burning transport beached on the coast and said, “Finish it.” The Australian bow fighters would make another run at dusk. Nothing could be allowed to reach Lei. Nothing. The second strike launched at 17:30. Lner didn’t fly. His bomber needed a new engine. Instead, he stood on the runway and watched nine fresh B-25s take off into the setting sun. They’d be over the target at dusk. The Japanese survivors would be trying to salvage what they could from the beach to transport.

They wouldn’t expect another attack. they’d be wrong. The strike returned at 2000 hours. The beached transport was gone, sunk at its mooring. The two damaged destroyers had been caught trying to withdraw, both hit, both sinking. The Japanese had started this operation with 16 ships. By nightfall on March 2nd, 14 were on the bottom of the Bismar Sea. The remaining two destroyers limped into Rabbal at midnight, barely afloat. The cost in lives was catastrophic. 7,000 Japanese soldiers had embarked at Rabbau.

Reconnaissance flights over the next 2 days counted approximately 900 survivors reaching the New Britain coast by lifeboat or swimming. American PT boats intercepted most of the lifeboats. Some survivors were rescued. Others were killed in the water. The distinction between combat and massacre blurred in those three days. Command ordered no quarter. The Japanese had machine gunned American air crew and parachutes. The Americans returned the favor to soldiers and lifeboats. Lner learned about it 3 days later. He didn’t ask for details.

Didn’t want to know which PT boat crews had fired on lifeboats, which bomber crews had strafed survivors swimming for shore. The war had rules until it didn’t. The rules had stopped applying somewhere between Mitchell’s bomber disintegrating and the last Japanese transport going under. Nobody talked about it. Nobody wrote it in afteraction reports. It happened anyway. The final count came through on March 7th. Japanese losses, eight transports sunk, four destroyers sunk. Approximately 3,000 troops drowned. Another 1,500 killed by air attack.

1,200 reached Lelay overland through the jungle. They arrived without weapons, without supplies, without organization. They were combat ineffective. The reinforcement operation had failed completely. American losses, four B-25s, one B7, two P-38s, 13 air crew killed, six wounded. Against an entire Japanese convoy, the exchange rate was absurdly one-sided. Skip bombing had worked, but it had worked because Larner’s crews had been willing to fly straight at destroyers at 50 ft, while anti-aircraft fire turned the air into metal. Courage didn’t cover it.

Insanity was closer. Kenny called it the most decisive air sea battle of the Pacific War. Admiral Yamamoto called it a disaster. The Japanese Navy immediately cancelled all future large convoy operations within range of Allied land-based air power. The supply line to New Guinea was cut. The garrisons at Lei, Salamawa, and Madang would have to survive on what they had. They wouldn’t survive long. But the Battle of the Bismar Sea changed more than Japanese strategy. It changed how every air force in the world thought about attacking ships.

The Americans refined skip bombing. The British adopted it. The Soviets copied it. By 1944, lowaltitude bombing had become standard doctrine for maritime strike aircraft worldwide. Lner flew 16 more missions before rotating home in May. He never spoke publicly about the battle, never gave interviews, never wrote a memoir. He’d done what was necessary. That was enough. The question nobody could answer was simple. Would the same tactic work against a prepared enemy? The Japanese tested that question three months later.

On June 3rd, 1943, American reconnaissance spotted another convoy forming at Rabool. Six transports, eight destroyers. This time the Japanese ship sailed at night. This time they had 60 zero fighters providing continuous air cover. This time, every destroyer carried additional 20 mm anti-aircraft guns specifically positioned to defend against lowaltitude attacks. They’d learned from the Bismar Sea. They’d adapted. The Fifth Air Force attacked at dawn. 12 B25s using skip bombing. The results were different. Two transports hit. One destroyer damaged.

Three B25s shot down. The exchange rate had shifted. The Japanese anti-aircraft defense had improved dramatically. Gunners who’d survived the Bismar Sea had trained their replacements. They knew to track low. They knew to fire early. They knew to concentrate on the bombers during the final approach when the aircraft were committed and couldn’t maneuver. The Americans adapted in return. By July, Fifth Air Force mechanics had installed additional armor around the cockpit and engines. They’d increased the forward-firing armament to 1250 caliber machine guns.

Some B-25s carried 14 guns. The theory remained the same. Suppressed defensive fire with overwhelming firepower during the approach. Give the enemy gunners no choice except take cover or die. The modification worked. On November 2nd, 1943, 38 B25s attacked Rabool Harbor in the largest skip bombing raid of the war. The harbor contained 18 warships, 30 received direct hits, one heavy cruiser sunk, one destroyer sunk, two auxiliary vessels destroyed, 16 merchant ships damaged or sinking. The raid lasted 18 minutes.

American losses, two B25s. The exchange rate had swung back in America’s favor, but Rabul proved something else. Skip bombing worked best against ships in confined waters, ships that couldn’t maneuver freely, ships anchored in harbor or trapped in narrow straits. Against a convoy in open ocean with room to maneuver and fighter cover overhead, the tactic was dangerous. Against ships at anchor, it was devastating. The British adopted skip bombing in late 1943. Royal Air Force bow fighters equipped with the technique attacked German convoys off Norway.

The results mirrored the Pacific experience. High casualties, high success rate. The Germans responded by adding more anti-aircraft guns to their merchant vessels and requiring convoys to sail only under heavy fighter escort. The cost of moving supplies by sea increased dramatically. The effectiveness decreased proportionally. The Soviets used skip bombing against German ships in the Black Sea and Baltic. Their technique was crudder. Lower approach altitude, heavier bombs, less suppressive fire. The results were mixed. Some ships sunk. Many bombers lost.

The Soviets had courage. They lacked the training and equipment refinement the Americans had developed through trial and error in the Pacific. By 1944, skip bombing had evolved beyond its original form. American tactics now included coordinated attacks. Highaltitude bombers would attack first, forcing ships to maneuver. Fighters would strafe to suppress anti-aircraft fire. Then the skip bombers would come in low while the defenses were distracted and disorganized. The multi-layered approach reduced losses while maintaining effectiveness. The statistics told the story.

Between March 1943 and August 1945, American aircraft using skip bombing sank or severely damaged 212 Japanese vessels. The cost was 47 bombers lost. A kill ratio of 4.5 ships per bomber. For comparison, high altitude bombing achieved a kill ratio of 0.3 ships per bomber. Skip bombing was 15 times more effective. But the human cost was harder to quantify. Skip bombing required crews to fly directly at ships bristling with weapons, maintaining a steady course while tracers filled the air around them.

The psychological stress was immense. Pilots who flew skip bombing missions had shorter combat tours, higher rates of combat fatigue, more frequent medical groundings for stress related conditions. The tactic worked. It also broke the men who flew it. Lner never flew skip bombing again after May 1943. He trained new crews, watched them take off on missions using the tactic he’d helped prove. Watch some of them not come back. By war’s end, he trained 62 pilots in skip bombing.

18 were killed in action. 23 were wounded. The mathematics were brutal. A 29% fatality rate, a 66% casualty rate, including wounded, better than high altitude bombing, worse than almost any other combat aviation role. The question military historians would debate for decades was whether skip bombing shortened the war. The answer was complicated. Skip bombing didn’t win battles by itself, but it strangled Japanese supply lines, made reinforcement prohibitively expensive, forced the Japanese Navy to abandon large-scale convoy operations. Without supplies, garrisons withered.

Without reinforcements, defensive positions became indefensible. The islands fell one by one. What remained certain was this. On March 2nd and 3rd, 1943, nine B-25 bombers flying at 50 feet had destroyed an entire Japanese convoy in 15 minutes of sustained combat. The tactic had been banned twice, called suicide by everyone who heard it, proven effective by men willing to fly into walls of anti-aircraft fire because the alternative was letting 7,000 enemy soldiers reach their destination. The bombers that attacked the Bismar Sea convoy were scrapped after the war.

None survived as museum pieces. Major Ed Larnner returned to the United States in June 1943. He was 31 years old. He’d flown 88 combat missions. He’d survived longer than most bomber pilots in the Pacific. The Army Air Force wanted him to train new crews, teach them what he’d learned, pass on the techniques that had worked. He refused. Lner requested and received a transfer to transport aircraft. He spent the rest of the war flying C-47s, moving supplies and personnel across the Pacific.

No combat, no skip bombing, no more missions where he watched crews he’d trained die in aircraft he’d taught them to fly. He never explained the decision, never had to. Command understood. Some men could keep flying combat after what they’d seen. Others couldn’t. There was no shame in either choice. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in December 1943. He declined the promotion twice before accepting. He didn’t want recognition. He wanted to finish the war and go home. He got his wish in September 1945.

Japan surrendered. Lner mustered out 3 months later with a distinguished flying cross, two air medals, and a Purple Heart from shrapnel wounds he’d never mentioned in any afteraction report. Lner died in 1997 in Sacramento, California. He was 85 years old. His obituary in the local newspaper mentioned his military service in one sentence. It didn’t mention the Battle of the Bismar Sea. Didn’t mention skip bombing. Didn’t mention that he’d helped develop a tactic that changed naval warfare. He’d asked his family not to discuss it.

They honored his request. General George Kenny received credit for skip bombing in most historical accounts. That was fine with Lner. Kenny had conceived the theory. Lner had just proven it worked. The distinction mattered to historians. It didn’t matter to the pilots who flew the missions. They knew who’d led the first attack. They knew who’ trained them. They knew whose techniques kept them alive when Japanese gunners were tracking their approach at 50 ft. The B-25 Mitchell bomber became legendary partly because of skip bombing.

The aircraft served in every theater of World War II, but its reputation was built in the Pacific, flying missions that shouldn’t have been survivable. By wars end, B25s had sunk more enemy shipping than any other bomber type. The technique LNER and his crews had proven in March 1943 became standard doctrine for every B-25 unit in the Pacific. No museum displays a B-25 specifically flown in the Battle of the Bismar Sea. The aircraft were worn out by wars end.

Most were scrapped for aluminum. A few survive in museums, restored to flying condition or displayed as static exhibits. The National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio has a B25 Mitchell. So does the Smithsonian. Neither flew at the Bismar Sea, but they represent the crews who did. The battle itself is largely forgotten outside military history circles. It doesn’t have the name recognition of Midway or Guadal Canal. No major films were made about it. No famous photographs captured the moment.

Just after action reports, reconnaissance images, and the testimony of men who mostly chose not to talk about what they’d done. What remains is this. In March 1943, a group of American bomber crews proved that aircraft could sink ships by skipping bombs across water at 50 ft altitude. The tactic was called suicide. before they proved it worked. It was called genius afterward. The truth was somewhere between. It was desperation meeting innovation. It was men willing to try something untested because the tested methods weren’t working.

It was courage measured in the decision to maintain heading while anti-aircraft fire turned the air lethal. The Pacific War changed after the Bismar Sea. Japanese convoys stopped sailing within range of Allied air power. Supply lines collapsed, garrisons starved, islands fell. The war moved closer to Japan one island at a time, and the Japanese Navy couldn’t stop it because they couldn’t supply their forward positions. Skip bombing hadn’t won the war by itself, but it had closed the supply route the Japanese needed to keep fighting.