The year is 1941 and America’s about to enter the biggest war in human history with a military that refuses to believe black men can fly combat aircraft. The Army Airore has spent two decades insisting that African-Ameans lack the intelligence, courage, and reflexes for aerial combat. But Elellanar Roosevelt isn’t buying it. After taking a flight with chief civilian instructor Charles Chief Anderson at Tuskegee Institute in April 1941, she puts pressure on her husband’s administration. The result, public law 18 passed in January 1941, forcing the War Department to create an all black flying unit whether they like it or not.

They don’t like it. Not one bit. The Army Air Corps picks Tuskegee, Alabama, the heart of Jim Crow territory specifically because it’s isolated, rural, and far from prying eyes. If these men are going to fail, and the brass fully expects them to fail, it’ll happen quietly. Tuskegee Army Airfield opens in July 1941 with equipment other bases rejected. The runways are shorter. The aircraft are older. The maintenance facilities are makeshift. Everything about the setup screams sabotage, disguised as compliance.

The first class of aviation cadets arrives to find instructors who’ve been told these students will wash out at triple the rate of white cadets. Captain Benjamin O. Davis Jr., West Point graduate and son of the Army’s first black general, leads the charge. He’s already spent four years at the military academy where not a single white cadet spoke to him outside of official duties. Now he’s facing an even more hostile test, proving that black men can master the most technologically demanding form of combat in existence.

The training is deliberately brutal. White cadets at other bases get multiple chances to pass check rides. Tuskegee cadets get one. White cadets who struggle with navigation get remedial instruction. Tuskegee cadets who show weakness get eliminated. The failure rate is engineered to be catastrophic. But something unexpected happens. These men refuse to break. The first class of five pilots earns their wings on March 7th, 1942. Davis, George Roberts, Benjamin O. Davis Jr., M. Ross, and Lemule Custous. The impossible has happened and the Army Air Corps has no choice but to continue the program.

By mid 1943, enough pilots have graduated to form the 332nd Fighter Group with four squadrons, the 99th, 100th, 301st, and 3002nd. Each squadron uses the standard Army Air Force’s structure, 16 aircraft, 25 pilots, and 200 ground crew. But nothing about these units is standard. Every mechanic, every crew chief, every supply officer is black. The Army has created a completely segregated combat group, betting that it’ll collapse under its own weight once real combat begins. The equipment tells you everything you need to know about their expectations.

While white fighter groups receive the latest P47 Thunderbolts and P38 Lightnings, the 332nd gets handme-down P40 Warhawks, the same aircraft being phased out of frontline service. These planes are slower, less maneuverable, and mechanically worn. It’s vintage 1941 technology going up against the Luftwaffa’s latest fighters in 1943. The message is clear. Perform your token missions, prove the critics right, and fade into history as a failed experiment. Colonel Davis takes command, knowing every mission will be scrutinized differently. When white pilots lose bombers, it’s the fog of war.

When his men lose bombers, it’ll be proof that the entire race is unfit for combat. The pressure is suffocating. These aren’t just fighter pilots. They’re carrying the aspirations of 13 million black Americans who’ve been told they’re inherently inferior. Every takeoff is a political statement. Every landing is a reputation of scientific racism. And the stakes are about to get infinitely higher because in June 1943, the 332nd Fighter Group is shipping out to North Africa. Real combat is coming and the entire nation is watching to see them fail.

The 99th Fighter Squadron hits Sicilian airspace on June 2nd, 1943. And the reality of combat strips away every romantic notion about aerial warfare. Their first mission is escorting medium bombers to Pantilaria. And it goes smoothly enough. No enemy contact, no losses, just nervous pilots learning what flack looks like when it’s actually trying to kill you. But the honeymoon ends fast. On June 9th, the squadron encounters German Faulk Wolf 1 190s over the Mediterranean and Lieutenant Charles Hall scores the unit’s first aerial victory.

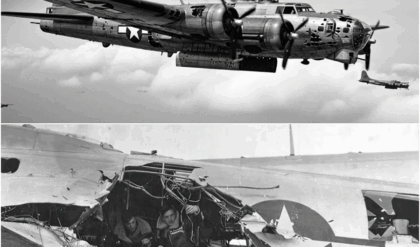

It should be a celebration, but the white commanders at Dukteen Air Support Command are watching with clipboards and skepticism. The P40 Warhawk is proving to be a death sentence in European skies. This aircraft was competitive in 1941, but by mid 1943, it’s outclassed by nearly every German fighter. The FW190 can outclim it by 500 ft per minute. The Messormidt BF 109G outturns it at high altitude. The P40’s top speed of 360 mph gets beaten by Luftwaffa fighters doing 390.

You can’t chase what you can’t catch, and you can’t escape what’s faster than you. The Tuskegee pilots are flying antiques into a modern war. July 2nd, 1943, the day everything nearly falls apart. During a mission over Castell Vatrono airfield in Sicily, the 99th gets jumped by a dozen BF 109s diving out of the sun. It’s a textbook ambush. Two P40s go down in flames. Lieutenant Sherman White is killed. Lieutenant James McCullen bails out over enemy territory and becomes a prisoner of war.

The remaining pilots scatter and the mission devolves into individual survival fights rather than coordinated combat. When they limp back to base, the recriminations begin immediately. Colonel William Mreir, commander of the 33rd Fighter Group, files a report that reads like a prosecution brief. He claims the 99th lacks aggressive spirit, shows poor formation discipline, and demonstrates inferior combat effectiveness compared to white squadrons. The report lands on General Hap Arnold’s desk with a recommendation. Pull the 99th from combat operations and use them for coastal patrol.

Basically, military busy work away from real fighting. Time magazine runs a story questioning whether the negro has the right temperament for aerial combat. Black newspapers fire back with editorials, but the damage is done. The experiment is being called a failure. Here’s what Mumir’s report doesn’t mention. His White Squadrons flying P40s are getting slaughtered, too. The 57th Fighter Group loses eight aircraft in July. The 79th fighter group loses six. The P40 is obsolete regardless of who’s flying it.

But when white pilots die, it’s bad luck. When black pilots die, it’s genetic inferiority. The statistics are being weaponized and the 332nd Fighter Group knows they’re one more bad mission away from being disbanded entirely. Colonel Davis requests an audience with General Ira Eker, commander of Mediterranean Allied Air Forces. It’s September 1943 and Davis walks into that meeting knowing he’s not just defending his squadron, he’s defending the entire concept of integrated combat forces. He brings mission reports, loss comparisons, and aircraft performance data.

The 99th has flown 500 sorties with a loss rate of 3.8%. White squadrons flying P40s have loss rates between 3.5 and 4.2%. Statistically, his men are performing identically to everyone else cursed with outdated aircraft. Eker doesn’t promote Davis on the spot, but he doesn’t ground the 99th either. Instead, he does something unexpected. He starts the paperwork to bring the entire 332nd fighter group to Italy and equip them with modern aircraft. It’s not charity. By late 1943, the strategic bombing campaign is hemorrhaging crews.

B17 and B-24 bombers are getting shredded over Germany, and the Army Air Forces needs every fighter group at Canfield. The Tuskegee airmen have proven they can survive. Now they’re going to get the chance to prove they can win. The 332nd ships to Ramatelli airfield in January 1944. And waiting for them on the flight line are rows of brand new P47 Thunderbolts. The equipment excuse just evaporated. Ramatelli airfield sits on Italy’s Adriatic coast, a muddy expanse of pierced steel planking and canvas tents that becomes home.

In January 1944, the 3032nd Fighter Group arrives expecting P47 Thunderbolts, and they get them for about two months. The P47 is a beast, a 7 fighter with 850 caliber machine guns and enough armor to fly through a brick wall. The pilots love it, but the 15th Air Force has different plans. By late May 1944, the group transitions again, this time to the P-51 Mustang. and everything changes. The P-51B and C models rolling onto Ramatelli’s flight line represent the cutting edge of American fighter technology.

With a Packard built Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, these aircraft crews at 360 mph and hit 440 at full throttle. Maximum range with drop tanks 900 m. That means Berlin is suddenly within reach from Italian bases, and the 15th Air Force needs every long range escort fighter it can muster. The strategic bombing campaign is burning through crews at an unsustainable rate, and somebody in command has finally done the math. Dead bomber crews don’t care what color their escorts are.

But here’s the catch. The 3003 second isn’t just getting Mustangs, they’re getting a new mission. Fighter sweeps and ground attack are out. Bomber escort is in. This is the most politically sensitive job in the entire air war because it puts black pilots directly responsible for white lives. If bombers get shot down while the 3032nd is supposed to be protecting them, every racist in the Army Air Forces will have ammunition for decades. Colonel Davis gathers his squadron commanders and lays out the stakes in blunt terms.

You will stay with the bombers. You will not chase glory kills. And you will bring those crews home. The Mustangs arrive in their standard olive drab and gray camouflage. But Davis orders something unprecedented. The entire tail assembly painted bright red. The 99th had used red trim on their P40s in North Africa. But this is different. These tails are fire engine red, visible from miles away, impossible to mistake for anyone else. The official reason is identification. Friendly bombers need to know their escorts at a glance.

The unstated reason is branding. If the 332nd is going to succeed or fail, everyone is going to know exactly who was flying escort. Those red tails become operational on June 7th, 1944 during a mission to Munich. 68 P-51s from the 30032nd join a formation of B17s from the fifth bombardment wing. And for the first time, bomber crews get a good look at their new escorts. The reaction is mixed. Some pilots are professionals who don’t care about skin color as long as the fighters do their job.

Others are southerners who’ve never taken orders from a black man and certainly didn’t expect to trust their lives to black pilots. The 332nd flies tight formation around the bombers, closer than the P47 groups typically fly, and the mission proceeds without incident, no bombers lost, no drama, just a milk run that proves nothing except that the Red Tail Mustangs can handle basic escort duty. But inside the bomber cruise, something is circulating. A rumor that won’t die. The Scuttlebutt says the 332nd has never lost a bomber to enemy fighters.

It’s not true yet, but the reputation is already forming. Part of this is timing. The Luftwaffa is getting bled white over Germany by summer 1944. Fuel shortages, pilot losses, and dispersed manufacturing mean the Germans can’t put up the 300 fighter swarms they fielded in 1943. The Red Tales are entering escort duty during a period when interception rates are dropping across the board. The skeptics in command are waiting for the 332nd to crack. They’re watching loss reports, counting bombers, and expecting the statistical anomaly to correct itself.

Standard doctrine says fighter escorts should engage enemy aircraft aggressively, even if that means leaving the bombers temporarily exposed. The theory is that dead German fighters can’t attack bombers. Every other fighter group follows this doctrine because it’s what the training manuals preach. Colonel Davis is about to throw that entire doctrine in the garbage. And the decision will define everything that comes after. The doctrine that’s killing American bomber crews in 1944 comes straight from the top. And it’s built on fighter pilot ego more than tactical reality.

The Army Air Forces teaches its fighter pilots that their primary mission is air superiority. Shooting down enemy aircraft to establish control of the sky. Bomber escort is treated as a secondary duty, almost an afterthought. The manuals explicitly encourage fighters to break formation and pursue enemy aircraft when opportunities arise. Kills equal promotions, medals, and glory. Staying with the bombers equals boring patrols that nobody writes home about. By March 1944, the numbers tell a brutal story. Eighth Air Force bombers flying out of England lose an average of 46 heavy bombers per 1,000 sorties.

That’s a 4.6% loss rate, which sounds manageable until you realize crews need to fly 25 missions to complete a tour. The math is savage. Statistically, your odds of surviving a full tour are roughly one in three. The 15th Air Force in Italy isn’t much better. Their loss rates hover around 3.8% 8% which still means entire squadrons are getting replaced every few months. The Luftwaffa has figured out the weakness in American tactics. German fighter commanders know the P-47s and P-51s will chase them if they present tempting targets.

So they use small decoy formations, four or five BF 109s flying provocatively near the bomber stream, waiting for the American escorts to take the bait. The moment the escorts break formation to pursue, larger German formations attack the now vulnerable bombers from different angles. It works horrifyingly well. On March 6th, 1944, bombers attacking Berlin lose 69 heavies in a single day. On March 8th, another 37 go down. The escorts are racking up impressive kill counts while the bombers they’re supposed to protect are getting slaughtered.

Here’s the dirty secret nobody wants to admit. Individual fighter pilots benefit from the current system even as it fails strategically. Captain Don Gentile of the fourth fighter group becomes a national hero with 21.8 confirmed kills. Many scored while chasing German fighters far from his assigned bomber formation. He’s on magazine covers while the bomber crews he abandoned are in P camps or dead. The incentive structure is completely backwards. Pilots who stick with the bombers get no recognition, while pilots who chase kills become celebrities regardless of how many bombers die on their watch.

The March 24th, 1944 mission to Berlin crystallizes everything wrong with American fighter doctrine. Over 700 bombers hit the German capital, escorted by 800 fighters, and the Luftwaffa throws everything available into the defense, 400 interceptors, including entire squadrons of FW190s and BF1009s. The German fighters use their standard tactics. Small groups faint at the bomber formations. American escorts take the bait and pursue. Then the main German force hits the exposed bombers. The result, 26 B17s and B-24s shot down over the target area with escort fighters miles away chasing decoys or engaged in individual dog fights that accomplish nothing strategic.

The mission reports from that Berlin raid make grim reading. Bomber crews describe watching their escorts disappear, chasing German fighters, then finding themselves alone when the main attack came. Ball turret gunners report seeing red-nosed FW190s attacking from below with no friendly fighters in sight. Radio operators send desperate calls for help that go unanswered because the escorts are too far away to respond. The crews return to base furious, filing complaints that go up the chain of command and get buried because admitting the doctrine is broken means admitting years of training and tactics need to be thrown out.

Colonel Davis reads these reports at Ramatelli and recognizes an opportunity. His group is already under a microscope. Every mission scrutinized, every mistake magnified. But that intense oversight also means he can’t hide behind the standard excuses that white fighter groups use when bombers get shot down. If the 303 second loses bombers while chasing glory kills, the entire experiment ends. But if his pilots can protect bombers better than white groups by simply staying where they’re supposed to be, that becomes undeniable proof of competence.

The pressure that’s meant to break them becomes the leverage they need to prove everyone wrong. Davis calls a meeting of his squadron commanders and issues orders that violate everything the Army Air Forcees teaches about fighter tactics. Stay with the bombers, no exceptions, no matter what. The orders Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr. issues in late March 1944 sound simple, but they require his pilots to ignore every instinct their training has drilled into them. Stay with the bombers. Don’t chase.

Don’t break formation for individual kills. If a German fighter flashes past, you let it go unless it’s directly threatening the bombers. The mission isn’t adding to your personal score. The mission is bringing every heavy back alive. For fighter pilots trained to be aggressive hunters, this feels like fighting with one hand tied behind your back. Davis doesn’t arrive at this doctrine through innovation. He arrives at it through necessity and observation. He’s watched the March 24th Berlin mission results.

He’s read afteraction reports from bomber crews describing their escorts vanishing at the worst possible moment. He’s also done something most fighter group commanders never bother with. He’s talked to bomber pilots, not formal debriefings, actual conversations where B17 and B24 crews explain what they need. What they need isn’t impressive kill counts. What they need is someone staying close when the FW190s come diving through the formation. The tactical implementation is specific and measurable. Standard escort doctrine calls for fighters to fly in a screen pattern, wide formations at various altitudes covering a general area around the bombers.

The 3082nd tightens that to what Davis calls close escort. His fighters fly within 50 yards of the bomber formations, close enough that bomber crews can see the pilots faces. When the bombers make turns, the escorts turn with them, maintaining position like they’re welded to the formation. When German fighters approach, the Red Tails maneuver to intercept without leaving their sector. This requires a level of flight discipline that most fighter groups consider unnecessary. Staying that close to 300 ft wingspan B17s, flying in tight formation means constant attention.

You can’t daydream. You can’t showboboat. One moment of inattention and you’re colliding with a bomber or drifting out of position. The physical demands are exhausting. Missions run six to eight hours and there’s no autopilot on a P-51. Your right hand stays on the stick making constant tiny corrections. Your left hand manages throttle and mixture. Your feet work the rudder pedals. Your head swivels, checking 6:00, 12:00, scanning for threats. Do this for 7 hours straight at 25,000 ft in sub-zero temperatures while breathing oxygen through a mask and you’ll understand why most fighter pilots prefer the freedom of independent sweeps.

The fuel management alone becomes an art form. The P-51 carries 269 gallons internally plus two 108gal drop tanks. That gives you roughly seven hours of endurance if you manage everything perfectly. Lean mixture for crews, drop tanks emptied and jettisoned at the right moment. No extended combat burns that guzzle fuel. Davis mandates strict fuel discipline. Pilots log their consumption every 15 minutes. They know exactly how many gallons they need to make it home, and if combat threatens to push them past the point of no return, they break off and head back.

This isn’t cowardice, it’s mathematics. A fighter that runs out of fuel and crashes in the Adriatic doesn’t protect anybody. The radio discipline is equally strict. Every other fighter group has pilots who can’t shut up, running commentary, jokes, combat chatter, cluttering the frequencies. The 3002nd maintains radio silence except for essential calls, enemy contacts, navigation updates, emergency situations. This isn’t just professional, it’s tactical. German radio operators monitor Allied frequencies and use the chatter to locate bomber formations. The less you transmit, the harder you are to track.

Meanwhile, the tight radio discipline means when someone does call out a contact, everyone hears it clearly instead of sorting through conversational noise. April 1944 becomes the proving ground. The 332nd flies escort for missions to Bucharest, Pesti, Vienna, Munich. Every strategic target in range, the Luftvafa is still capable of mounting serious opposition in spring 1944 and the interceptions are frequent. On April 12th, during a raid on the Styr ballbearing plant, German fighters make multiple passes at the bomber formation.

The Red Tails intercept every approach, shooting down three BF- 109s without a single bomber lost. April 15th, mission to Plloesty. Same result. German fighters engaged, bombers protected, everyone comes home. April 24th, April 26th, May 5th, mission after mission, the pattern holds. The 3002nd isn’t chasing kills deep into Germany. They’re doing something more valuable. They’re making bomber crews believe they might actually survive this war. The record that makes history doesn’t happen by accident. It happens through obsessive attention to details most fighter groups consider beneath them.

Between June 1944 and April 1945, the 332nd Fighter Group flies approximately 200 bomber escort missions totaling 15,553 sorties. The exact number of bombers escorted varies by source, but the consensus settles around 15,000 heavy bombers protected. The number lost to enemy aircraft while under their direct escort, zero. Not one. That statistical impossibility requires understanding how they engineered success through tactics most pilots would find boring. The formation geometry is everything. While other fighter groups fly loose formations that allow individual maneuvering, the 332nd uses what amounts to a moving perimeter defense.

Four squadrons rotate positions throughout the mission. High cover, low cover, and two side positions. The high squadron flies 2,000 ft above the bombers, scanning for diving attacks. The low squadron sits 1,000 ft below, watching for the Luftwaffa’s favorite tactic, attacking from underneath where the bombers have the weakest defensive fire. The side squadrons bracket the formation close enough to intercept any fighter trying to make a beam attack through the bomber stream. Every 15 minutes, the squadrons rotate positions.

High cover drops to low cover. Low cover rotates to the right flank. Right flank moves to left flank. left flank climbs to high cover. This rotation serves two purposes. It prevents fatigue from keeping one squadron in the most vulnerable position all mission, and it makes the defense unpredictable. German fighter controllers are tracking these formations, trying to identify weak points. Constant rotation means there’s never a sustained weakness to exploit. It’s exhausting to execute. Every rotation requires precise timing and communication, but it works.

The target area presents the greatest danger because bombers are most vulnerable during the bomb run. The lead bomber deer needs a stable platform for 30 to 60 seconds while the Nordon bomb site calculates the release point. The entire formation flies straight and level, unable to take evasive action. German fighters know this and they time their attacks for this window. The 332nd positions eight fighters directly alongside the lead bomber during the bomb run, four on each side, close enough to physically block any fighter trying to make a pass.

It’s aerial bodyguard work, requiring pilots to fly formation on bombers that are being hammered by flack, unable to maneuver, completely focused on keeping position rather than watching for threats. The engagement rules Davis establishes are brutally clear. You only pursue if you can maintain visual contact with the bombers. German pilots quickly learn that the Red Tails won’t chase, so they try different tactics. BF 109s make faint attacks, pulling away before entering gun range, trying to draw escorts out of position.

It doesn’t work. FW190s try diving attacks from 30,000 ft, building speed to blow through the escort screen. The high cover intercepts them on the way down. Mi410 heavy fighters attempt to attack from outside machine gun range using 210 mm rockets. The escorts stay tight, forcing the rocket carriers to fire from ineffective distances where hitting a maneuvering bomber is nearly impossible. The fuel calculation becomes a constant mathematical problem every pilot must solve in real time. A typical mission profile.

Take off from Ramatelli with full internal fuel and two drop tanks. Climb to 15,000 ft burning 150 gallons. Cruise to the target area at 25,000 ft, burning roughly 60 gallons per hour. Tanks empty after three hours. Jettison them. Internal fuel only now. Roughly 180 gall remaining. Combat engagement might burn 100 gall in 10 minutes at full throttle. That leaves 80 gall to make it home. And the base is still 400 m away. The margin for error is zero.

Pilots who misjudge by even 20 gallons don’t make the coast. They ditch in the Adriatic and hope the air sea rescue finds them before hypothermia does. The ground crews at Ramatelli perform miracles that make the zero loss record possible. These are black mechanics who’ve been told their entire lives they’re not smart enough for technical work and they’re maintaining complex machines with tolerances measured in thousandth of an inch. Every P-51 gets a complete inspection after each mission. Engine compression check, control surface rigging, gun bore sighting, oxygen system pressure test.

They catch problems before they become fatal. When a pilot reports rough engine running, the crew chief doesn’t wait for the next scheduled maintenance. He pulls the cowling that night and finds the fouled spark plug or loose connection. There are no excuses for mechanical failures because mechanical failures over Germany mean dead pilots and lost bombers. The math behind the record is relentless. 200 missions with an average of 78 sorties per mission equals 15600 individual opportunities for something to go wrong.

Mechanical failure, pilot error, German fighters, flack, weather. Any one of these could result in bombers lost while under escort. The fact that it doesn’t happen even once isn’t luck. It’s the result of doctrine that prioritizes mission success over individual glory and pilots disciplined enough to execute that doctrine perfectly for an entire year. The bomber crews notice first. You’re flying your 15th mission over Austria, watching the flack bursts get closer, waiting for the FW190s everyone knows are coming.

And you look out your cockpit window to see a red tail maybe 60 ft off your wing tip. That pilot isn’t scanning the horizon for targets. He’s watching you, matching your every move. A guardian who won’t leave regardless of what happens. You land back at Fogia or Amandola. And during debriefing, you mentioned those red tales to your squadron commander. He mentions it to the group commander. Word spreads through the fifth bombardment wing, then the 3004th, then across the entire 15th Air Force.

By summer 1944, bomber crews have a name for them, Red Tail Angels. The nickname isn’t official military terminology. It’s grassroots mythology spreading through the bomber groups at crew level. B17 pilots swapping stories in the officer’s club. Waste gunners talking in the messaul. Navigators comparing notes during mission planning. The consistent theme is reliability. Other fighter groups might show up. Might stick around, might be there when you need them. The 332nd always shows up, always stays, always brings you home.

It becomes the ultimate compliment from men who are understandably skeptical of promises after watching escorts disappear mission after mission. By October 1944, something unprecedented starts happening. Bomber crews request the 332nd by name. Mission planners for heavy bombardment groups specifically ask whether the Red Tails are available for escort duty on high-risk targets. This drives some white fighter group commanders absolutely insane. Colonel Hub Zama of the 479th Fighter Group files a complaint that bomber crews are showing preference for negro pilots, implying it reflects poorly on white fighter groups.

The complaint goes nowhere because the 15th Air Force Command looks at the lost statistics and shrugs. If bomber crews feel safer with the 332nd, maybe other fighter groups should start wondering why. The reputation creates a psychological weapon that works on multiple levels. German fighter pilots monitoring Allied radio frequencies hear bomber crews talking about the red tales. Luftwafa intelligence briefs its pilots. These are negro pilots who fly unusually tight formations and won’t abandon the bombers. Some German pilots don’t believe black pilots exist.

They assume it’s Allied propaganda. Others learn the hard way during failed attack runs that get intercepted by Mustangs that won’t leave their stations. The red tails become a tactical marker. If you see them, the bombers are going to be harder to hit because the escorts won’t give chase. The numbers by early 1945 are impossible to dismiss. The 332nd has flown 179 bomber escort missions without losing a bomber to enemy fighters. Compare this to other 15th Air Force fighter groups.

The 31st Fighter Group averages losing 2.3 bombers per 100 escort missions. The 52nd Fighter Group averages 2.1. The 325th Fighter Group averages 1.9. These aren’t incompetent units. They’re experienced groups with excellent pilots flying the same P-51s as the 30032nd. The difference is doctrine and the proof is in the loss sheets that colonels read every morning. March 24th, 1945 delivers the mission that cementss the legend. The target is Dameler Ben’s tank works in Berlin, over 600 m from Ramatelli, maximum range for the P-51s, defended by whatever’s left of the Luftwaffa.

The 332nd puts up 59 fighters escorting B17s from the fifth bombardment wing. Near the target, approximately 25 Messid Mi 262 jets, the world’s first operational jet fighters, attack the formation. The Mi262 flies 100 mph faster than a P-51, and conventional wisdom says piston engine fighters can’t catch jets. The Red Tails don’t chase them. They position themselves between the jets and the bombers, forcing the MI262s to maneuver to get attack positions. In the swirling fight, three jets go down.

Captain Rosco Brown gets one. Lieutenant Earl Lane gets another. Second Lieutenant Charles Brantley bags the third. It’s the only engagement where the 332nd shoots down three ME262s in a single mission, and every bomber comes home. The mission report circulates through every bomber base in Italy. Crews who weren’t there hear about it from crews who were. The story gets embellished. Some versions claim six jets shot down. Others say the Red Tales chased the jets all the way to their base.

The truth is impressive enough. In the war’s final months against Germany’s most advanced aircraft flown by experienced pilots, the 332nd protected the bombers and shot down three jets while staying in formation. The myth and the reality merge into something bomber crews can believe in. Undeniable proof that if the red tails are with you, you’re coming home. By April 1945, the zero loss record isn’t just statistics. its reputation, mythology, and tactical reality blended into something that changes how both sides fight.

Allied bombers fly with greater confidence when they see red tails. German fighters approach those formations with greater caution. And sitting in cockpits at 25,000 ft, black pilots who’ve been told their entire lives they’re inferior are proving every single day that excellence isn’t about skin color. It’s about discipline, doctrine, and refusing to quit. The war ends in May 1945, and the 332nd Fighter Group returns to the United States with a record that nobody can dispute and nobody wants to celebrate publicly.

They’ve flown 1,578 combat missions, destroyed 112 enemy aircraft in the air, another 150 on the ground, sunk a destroyer with machine gun fire, and accumulated 96 distinguished flying crosses. The zero bomber loss record, officially recognized as losing bombers at a rate lower than any other 15th Air Force fighter group, becomes the irrefutable answer to every claim that black men can’t handle complex military operations. But America in 1945 isn’t ready for that conversation. The military tries to bury them with silence.

There are no ticker tape parades for the 332nd, no national radio broadcasts celebrating their achievements. The white press largely ignores them while extensively covering other fighter aces. Colonel Davis receives the Silver Star, but doesn’t get promoted to Brigadier General until 1954, 9 years after the war ends, while white officers with less distinguished records pin on stars within months of returning home. The Tuskegee airmen go back to an America where they can’t eat in the same restaurants as the bomber crews they protected, can’t drink from the same water fountains, can’t live in the same neighborhoods.

But the record itself becomes a weapon in the civil rights arsenal because it’s mathematically undeniable. When segregationists claim black soldiers performed poorly in World War II, civil rights advocates point to the 332nd. When military planners argue against integration, they have to explain why the most effective bomber escort group was all black. President Truman signs Executive Order 9981 in July 1948 mandating integration of the armed forces and the Tuskegee Airman’s record is part of the evidence stack that makes segregation indefensible.

You can’t claim a race is inferior when they’ve proven superior performance under the most objective measurements possible, combat effectiveness, and mission success rates. The tactical doctrine they pioneered becomes standard training for fighter escorts within a decade. The stay with the bombers principle that Colonel Davis fought to implement becomes official air force policy during the Korean War. Modern fighter doctrine for escort missions emphasizes maintaining position with protected assets rather than pursuing individual kills, exactly what the 332nd practiced in 1944.

The F-15 Eagle’s development in the 1970s includes specific design requirements for long range escort capability, directly influenced by lessons learned from World War II bomber protection. The Tuskegee Airman’s tactics outlived the prejudices that tried to prevent them from flying. The Hollywood version takes decades to arrive. The 1995 HBO movie The Tuskegee Airman introduces millions of Americans to the story. The 2012 film Red Tales brings it to theaters, though with significant historical simplifications. These portrayals have flaws. They compress timelines, create composite characters, exaggerate some combat sequences, but they accomplish something vital.

They force the American narrative about World War II to include the men who were deliberately excluded for 50 years. Schools that never mentioned black pilots suddenly have lesson plans about the Tuskegee Airmen. Veterans groups that ignored them for decades invite them to speak. The survivors become living links to a history the nation tried to forget. Lieutenant Colonel George Hardy, who flew 21 missions with the 332nd, attends air shows into his 90s, telling crowds about fighting two wars simultaneously, one against the Germans, one against the racism of his own military.

Brigadier General Charles McGee flies 409 combat missions across three wars and becomes the visible face of the Tuskegee legacy. Speaking to militarymies about the doctrine that saved lives, these men don’t claim they were perfect. They claim they were given an impossible standard and met it through discipline when natural talent alone would have failed. The final vindication comes in 2007 when President George W. Bush awards the Congressional Gold Medal collectively to the Tuskegee Airmen. Approximately 300 survivors attend the ceremony, old men in their 80s and 90s, many in wheelchairs, some requiring oxygen, all wearing their distinctive red blazers.

Bush’s remarks acknowledge what the government denied for 60 years. These men were subjected to a double standard, performed beyond it, and changed the military forever. The medal doesn’t erase the discrimination they faced. It doesn’t compensate for the decades of denial. But it’s official recognition that their service mattered, and their record stands. Today’s Air Force trains every pilot on case studies that include the 332nd Fighter Group’s escort doctrine. The precision, discipline, and mission focus they demonstrated become teaching examples at squadron officer schools and fighter weapon schools.

When modern fighter pilots discuss close air support or protected asset escort, they’re implementing tactical principles refined under fire by men who weren’t supposed to be capable of flying at all. The Tuskegee airmen didn’t just prove they could fly. They proved they could innovate, adapt doctrine, and execute with a level of discipline that set new standards. They started by escorting closer than regulations required and ended by changing what excellence looked like for everyone who followed.