At 4:47 a.m. March 14th, 1944, Anio Beach Head, Italy, Corporal Vincent Vinnie Calabrace lay in a shell crater 40 yard from German lines, watching five spotters through a scope he’d modified against direct orders. The spotter sat in a ruined farmhouse window. Coordinates rolling off their lips into field radios, directing 88 mimic fire that had killed 11 Americans in the past 6 hours.

Standard doctrine said, “Take them one at a time. One shot, one spotter, four chances for the others to scatter and call in your position before you could work the bolt.” Vinnie had a different idea. an illegal idea, one that could put him in front of a firing squad if it failed. In the next 90 seconds, he would break three regulations, violate the manual of arms, and fire a shot that shouldn’t exist.

The German spotters would die before they understood what hit them. and the United States Army would spend six months trying to decide whether to hang him or promote him. Vincent Calibracy grew up in Red Hook, Brooklyn, where the Gowanas Canal smelled like diesel and dead fish, and every man over 16 worked the docks or the shipyard.

His father unloaded merchant vessels. His uncle S repaired ship engines. Vinnie learned early that if something was broken, you fixed it yourself because waiting for the company to fix it meant you didn’t eat. At 14, he was modifying car engines in his uncle’s garage. Nothing fancy. Timing adjustments, carburetor tweaks, small changes that made big differences.

He had a feel for mechanical rhythm, for understanding why things worked the way they did and how they could work better. He also had a temper. Three fights before he turned 16. One suspension. His mother said he had angry hands, but a thinking brain, and she didn’t know which would ruin him first. December 1941 solved that question.

He enlisted two days after Pearl Harbor. The army tested him, found he could shoot straight, and handed him a Springfield 1903 rifle. They made him a scout sniper, sent him to North Africa, then Sicily, then mainland Italy. By March 1944, he’d been at Anzio for 7 weeks. The beach head was a meat grinder.

32,000 men trapped in a pocket 6 mi deep, 16 mi wide with German artillery on the high ground. found raining shells down every hour of every day. The spotters were the problem. German forward observers hidden in farmhouses, church steeples, tree lines. They watched Allied movements through binoculars and called coordinates to AD meter batteries positioned in the hills.

American snipers could take out one spotter, maybe two, before the others relocated. The Germans knew this. They positioned spotters in groups, betting that American doctrine, one shot, one target, would give the others time to escape. It worked. The casualty rate among American infantry at Anio was 38%. Artillery caused most of it.

Vinnie watched men die because of those spotters. Private Tommy Reachi from Philly blown apart by an 88 round while carrying ammunition. Sergeant Bill Hooper from Kansas killed by shrapnel while digging a foxhole. Corporal Eddie Garrett from Tennessee obliterated when a shell landed directly on his position.

All three died because a German spotter in a window called in their location. Vinnie knew Richi. They’d shared rations two days before he died. Hooper had loaned Vinnie a pair of dry socks. Garrett taught him a card game from Memphis. Now they were gone, and more spotters sat in more windows, calling in more death.

Standard doctrine said snipers engaged one target at a time. Fire. Work the bolt. Reacquire. Fire again. The Springfield 1903 was a five round internal magazine bolt-action rifle. Accurate, reliable, slow. Between shots, a trained sniper needed 3 to 4 seconds to cycle the bolt, reacquire through the scope, and fire again.

4 seconds was enough time for a spotter to shout a warning, grab his radio, and disappear. 4 seconds meant the other spotters scattered like rats and you’d wasted your position for one kill. Vinnie watched it happen a dozen times. A sniper would drop one spotter, the others would vanish.

30 minutes later, they’d reappear somewhere else and the shells would start falling again. The math was brutal. Five spotters in a window kill one. The other four escape, relocate, and kill 10 Americans before the day ends. He brought this up to Lieutenant Hargrove, his platoon leader.

Hargrove was a West Point graduate who believed the manual was gospel. “You engage the primary target,” Hargrove said. “Then you displace.” “That’s doctrine,” Corporal sir. By the time I displace, the other spotters are gone. They reposition and we get shelled again. The Springfield isn’t designed for rapid fire. You want rapid fire? Grab a Garand. The Garand doesn’t have the range, sir. Then follow Doctrine, Corporal.

Dismissed. Vinnie followed Doctrine. He killed spotters one at a time. He displaced. The other spotters escaped. Men kept dying. On March 9th, a German artillery barrage hit a forward aid station. 14 wounded men died along with two medics. One of the medics was a kid from Boston named Jimmy Lynch, 20 years old, wrote letters to his mother every 3 days.

Vinnie had watched him splint a broken leg under fire two weeks earlier. Now Lynch was a name on a casualty list. That night, Vinnie sat in his foxhole, Springfield across his lap, thinking about timing. The problem wasn’t the rifle. The Springfield was accurate out to 800 yd. The problem was the bolt. Every time he cycled it, he lost 4 seconds. 4 seconds, the spotters used to run.

But what if he didn’t cycle the bolt? What if he could fire five rounds? every round in the magazine before the spotters even registered the first shot. The idea violated physics. The Springfield was bolt action. You fired, worked the bolt to eject the spent casing and chamber a new round, then fired again. There was no mechanism for automatic fire. No gas system. No way around it unless you change the timing.

Vinnie had grown up modifying engines. Engines were about timing, combustion, compression, exhaust. Change the timing, and you changed performance. Rifles were the same. They were combustion engines that shot lead instead of turning wheels. The Springfield’s bolt locked into battery with two forward lugs.

When you fired, gas pressure pushed the bullet down the barrel. The bolt stayed locked. After the bullet left, you manually worked the bolt. Pull back. Eject casing. Chamber. New round. Push forward. Lock. But what if the gas pressure could work the bolt for you? Vinnie turned the idea over in his mind. Gas pressure.

The Springfield wasn’t designed to harness it, but gas was escaping from the barrel every time he fired. If he could redirect some of that gas backward, create a pressure wave that pushed the bolt open after the bullet left, he could cut the cycle time from 4 seconds to maybe half a second. It was insane.

It violated the rifle’s fundamental design. It would require drilling into the barrel, installing a gas port, rigging a piston system to push the bolt, modifying the trigger group to release the firing pin automatically when the bolt closed. It would take hours. It would void every regulation in the manual. If it failed, the rifle could blow up in his face.

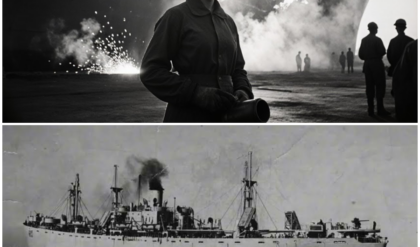

If it worked and anyone found out, he’d face court marshall for destroying government property. And if he did nothing, more men would die. March 11th, 2:30 a.m. Vinnie worked in a supply tent near the beach head perimeter. He’d told the sentry he was cleaning his rifle. The sentry didn’t care. Nobody cared what you did at 2:30 a.m. as long as you didn’t make noise.

He had the Springfield disassembled on a crate, barrel, bolt, trigger group, stock, every piece laid out like an engine he was rebuilding in his uncle’s garage. The smell of gun oil filled the tent. Outside, a distant rumble of artillery echoed from the hills. The Germans fired harassment rounds at night just to keep everyone from sleeping. Vinnie worked by flashlight, his hands steady despite the cold.

Step one, drill a gas port in the barrel. He’d borrowed a hand drill from the engineers. The barrel was forged steel, hard as a ship’s hull. He measured 6 in from the chamber, marked the spot with a grease pencil, and started drilling. The bits screeched against the metal. He drilled slowly, checking depth every few minutes. Too shallow and the gas wouldn’t vent.

Too deep and he’d weaken the barrel. 15 minutes. The drill bit punched through. He inspected the hole clean 1/8 in diameter. He blew metal shavings out and wiped the barrel down. Step two, fabricate a gas piston. He didn’t have a machine shop. He had a tent, a file, and scrap metal from a destroyed German halftrack. He cut a piece of steel rod, filed it down until it fit inside a tube he’d fashioned from a broken radio antenna.

The piston had to slide smoothly, but tight enough to seal. He tested it 20 times, filing and adjusting until the fit was perfect. Step three, attach the piston system to the barrel. He used wire scavenged from Comm’s equipment, wrapping it tight around the barrel to secure the gas tube. The tube ran from the gas port back toward the receiver, angled to catch escaping gas, and push the piston.

The piston connected to the bolt via a thin steel rod he’d bent and filed. His hands were black with grease. His fingers achd. He cut his thumb on a sharp edge and wrapped it with a strip of cloth torn from his undershirt. Step four, modify the trigger group. This was the dangerous part. The trigger had to release automatically when the bolt closed so the rifle would fire again without him pulling the trigger.

He filed down the sear, adjusted the hammer spring tension, and tested the mechanism by hand. The hammer snapped forward with a sharp click. Too much tension, and it wouldn’t reset. Too little and it might misfire. He adjusted, tested, adjusted again. 40 minutes of trial and error, his fingers cramping in the cold. By 4:15 a.m., the rifle was reassembled.

It looked almost normal. The gas tube was hidden along the barrel, camouflaged with mud and cloth wrapping. The internal modifications were invisible unless you disassembled the action. Vinnie held the rifle in his hands and felt the weight of what he’d done. If this worked, he’d created something that didn’t officially exist.

If it failed, he’d destroyed a piece of military equipment and risked his life on a theory. He loaded five rounds into the magazine, walked outside into the pre-dawn darkness, found a spot behind the supply tent where nobody would see him, aimed at a patch of dirt 40 yard away. He pulled the trigger. The rifle fired.

The recoil punched his shoulder. The gas system worked. He heard the bolt cycle, a metallic clack as the piston drove it back. The spent casing ejected. A new round chambered. The rifle fired again. Boom. Clack. Boom. Clack. Boom. Five rounds in two seconds. The rifle kicked like a mule. The barrel heated fast, but it worked.

Vinnie stood there, smoke curling from the barrel, his ears ringing. He’d just turned a bolt-action rifle into something resembling a semi-automatic. It shouldn’t have worked, but it did. Now he just had to use it without getting caught. March 14th, 4:30 a.m. Intelligence reported five German spotters in a farmhouse 600 yd beyond the wire.

The spotters had called in three artillery strikes overnight, killing six Americans and wounding 11 more. Vinnie volunteered for the patrol. Lieutenant Hargrove approved it without looking up from his map. One target, Calibracy, then displace. Yes, sir. Vinnie crawled through the wire at 4:15 a.m. The ground was cold and wet. Mud soaked through his uniform.

He moved slowly, rifle cradled in his arms, avoiding open ground where flares might expose him. The farmhouse sat on a low rise, its secondstory windows facing the American lines. He found a shell crater 40 yards from the house and settled in. The crater stank of cordite and rotting earth. He wedged the rifle against the crater’s edge, using a rolled blanket as a rest.

Through the scope, he could see the farmhouse window. Five shapes. German spotters dressed in field gray hunched over radios and map tables. One of them held binoculars, scanning the American lines. Another spoke into a radio handset, his mouth moving as he relayed coordinates. Vinnie’s heart hammered in his chest. Five targets. Standard doctrine said take the one with the binoculars first, then displace before the others reacted, but if his modification worked, he could take all five before they understood what was happening. He adjusted his breathing,

slowed his heartbeat. The crosshairs settled on the first spotter’s chest. 600 yd, no wind, clear shot. He pulled the trigger. The rifle fired. The first spotter jerked backward, the binoculars falling from his hands. The gas system cycled. The rifle fired again. The second spotter’s head snapped back. The rifle fired again.

The third spotter collapsed across the map table again. The fourth spotter spun and fell again. The fifth spotter dropped, the radio handset slipping from his grip. Five shots, two seconds. The German spotters died before the sound of the first shot reached them.

They had no time to shout a warning, no time to grab their weapons, no time to understand what was happening. One moment they were alive, the next they weren’t. Vinnie cycled the bolt manually to eject the fifth casing. The barrel was hot against his hand. Smoke drifted from the muzzle. He scanned the window through the scope. No movement. Five bodies sprawled across the floor and furniture. He waited.

10 seconds. 20. No reaction from inside the farmhouse. No German soldiers rushing to investigate. No return fire. He crawled backward out of the crater, dragging the rifle with him. 50 yards. 100. He reached the wire and slipped through. Made it back to his foxhole as the sun broke over the hills.

Nobody had heard the shots. The distant rumble of artillery had covered the sound. Nobody knew what he’d done except the German spotters were dead. All five of them. And for the first time in 7 weeks, the American lines didn’t get shelled at dawn. Vinnie sat in his foxhole cleaning the rifle. The barrel was still warm.

He ran a patch through it, watching black residue come out on the cloth. The modification had worked. The gas system hadn’t blown up in his face. The rifle had cycled five times without jamming. He felt nothing. No triumph, no satisfaction, just a dull awareness that he’d killed five men in two seconds using a weapon that wasn’t supposed to exist.

Corporal Danny Russo appeared at the edge of the foxhole. Russo was a rifleman from the Bronx, 30 years old, with a scar across his chin from a bar fight in Sicily. He stared at Vinnie. “You took out that spotter nest.” Vinnie didn’t look up. Yeah. All five spotters. Yeah. In one go. Yeah. Russo climbed down into the foxhole. He looked at the rifle, then at Vinnie.

How? Vinnie kept cleaning. Trade secret. Calibracy. We’ve been getting shelled by those spotters for 3 days. You just killed all five before they could scatter. How the hell did you do that? Vinnie set the rifle down. He looked at Russo. You really want to know. Yeah, it’s not regulation. I don’t care, Vinnie explained.

The gas port, the piston, the modified trigger group. Russo listened without interrupting. When Vinnie finished, Russo was quiet for a long moment. Then he said, “You drilled a hole in a government rifle.” Yeah, modified the trigger. Yeah, that’s destruction of military property. I know. If Harrove finds out, you’re looking at court marshal. I know.

Russo picked up the rifle, examined the gas tube wrapped along the barrel, tested the bolt action, set it down carefully. Does it work every time? Worked this morning. How many rounds? Five. That’s the magazine capacity. Russo nodded slowly. Five rounds in two seconds. Jesus Christ. Calibr. You built a machine gun out of a Springfield. Not a machine gun. Semi-automatic. Still

have to aim. Still. Five spotters in one sweep. That’s illegal. That’s brilliant. Russo left the foxhole. By noon, three other snipers had visited Vinnie’s position. By evening, word had spread through the scout platoon. Nobody told Lieutenant Hargrove. Nobody wrote a report, but snipers started asking Vinnie questions. Detailed questions.

How deep was the gas port? What diameter? “How did you attach the piston?” Vinnie answered reluctantly. He didn’t want credit. He didn’t want attention. He wanted men to stop dying because German spotters had 4 seconds to run. On March 16th, a sniper named Frank Delaney came back from a mission with three confirmed kills.

All three were spotters positioned in a church steeple. Delaney had modified his rifle using Vinnie’s method. “Took them out before they knew I was there,” Delaney said. No displacement, no counterfire, just three dead spotters and me walking back. By March 20th, eight snipers at Anio had modified their rifles.

They didn’t ask permission. They worked at night using borrowed tools and scavenged materials. The modifications were crude. Some used copper tubing instead of steel. Others filed down springs that didn’t quite fit, but they worked. Five round bursts instead of single shots. Spotter nests wiped out in seconds.

The German artillery slowed, not stopped, but slowed. The casualty rate dropped from 38% in February to 29% in late March. 11 men saved for every hundred engaged. The German spotters noticed they started moving more frequently, stayed in positions for shorter periods, stopped grouping together in windows. But the damage was done.

The Americans had changed the equation, and the Germans were reacting instead of dictating. On March 24th, a captured German artillery observer was interrogated by intelligence. The transcript included this exchange. Interrogator, why have your spotting teams reduced their observation time? Prisoner: The American snipers have become more aggressive.

Interrogator, how so, prisoner? They fire multiple shots rapidly. Our spotters do not have time to relocate. We have lost 17 observers in 10 days. Interrogator. Multiple shots. The Americans use boltaction rifles. prisoner. I do not know how they do it, but they do. The interrogation report was filed and forgotten.

Nobody connected it to Vinnie Calibrazy or the gas operated Springfield rifles spreading through the sniper course. Nobody in American command. Anyway, the Germans knew something had changed. German intelligence analysts examined reports from Anzio and noted the increased sniper effectiveness. They interviewed survivors from spotter teams. The survivors described the same thing.

American snipers firing multiple rounds in rapid succession, faster than boltaction rifles should allow. One German sergeant pulled from the line after his spotter team was ambushed said this. The American fired five times before my partner could shout a warning. I saw the muzzle flash once. I heard five shots.

They came so fast I thought it was a machine gun, but it was a rifleman. One man, one rifle. Five of my team dead. German commanders adjusted their doctrine. Spotters worked alone now, not in groups. They changed positions every 30 minutes. They stopped using obvious vantage points like church steeples and farmhouse windows.

The adjustments helped, but not enough. The American snipers kept killing them. The artillery support dropped. German infantry deprived of accurate fire support became more cautious. By April 1944, the tactical balance at Anio had shifted. Not dramatically, not enough to break the stalemate, but enough that American infantry could move during daylight without drawing immediate artillery fire.

Enough that casualty rates stayed below 30% instead of climbing higher. And still no official report mentioned modified rifles or unauthorized modifications. The snipers kept their secret. They communicated through whispered conversations and shared tools. They taught each other the technique. Drill here. File this. Adjust that spring. Lieutenant Hargrove never noticed. Or if he did, he said nothing.

He watched his casualty numbers drop and assumed it was improved training or better luck. May 3rd, 1944, Captain Frank Mercer, Ordinance Department, arrived at Anzio to inspect weapons. Routine inspection, nothing unusual. He moved from foxhole to foxhole, checking rifles for wear, corrosion, unauthorized modifications.

He picked up a Springfield belonging to Corporal Danny Russo. examined the barrel. Saw the gas tube wrapped along the length. Frowned. What’s this? Russo hesitated. Field modification, sir. I can see that. Who authorized it? Nobody, sir. Mercer disassembled the rifle in 30 seconds.

Saw the gas port drilled into the barrel, the piston mechanism, the modified trigger group. His face turned red. This rifle has been illegally altered. Who did this? Russo said nothing. Koparo, I asked you a question. Russo met his eyes. I did it, sir. You drilled a hole in a government rifle? Yes, sir. Do you understand that’s destruction of military property? Yes, sir. Who taught you how to do this? Figured it out myself, sir.

Mercer didn’t believe him. He inspected six more rifles that day, all modified, all using the same gas operated system. He filed a report. The report went to Colonel Raymond Hayes, the Beach Head’s senior ordinance officer. Hayes read the report, read it again, called in his sergeant major. We have unauthorized weapon modifications, multiple snipers, same system, gas operated conversion of boltaction rifles.

The sergeant major, a 40-year-old named Tom Briggs, nodded. I’ve heard about it, sir. You’ve heard about it? Yes, sir. And you didn’t report it? Didn’t think it was my place, sir. It’s your place if soldiers are destroying government property. Briggs shifted his weight. Sir, the modifications work. Casualty rates down 11% since March.

Spotters aren’t calling in fire like they used to. Hayes stared at him. Are you telling me these illegal modifications are effective? Yes, sir. Hayes ordered an investigation. He wanted names. He wanted to know who started it, who taught it, who authorized it. The investigation took 3 days. Every sniper interviewed gave the same answer.

I modified my own rifle, figured it out myself. Nobody mentioned Vinnie Calibracy. On May 8th, Hayes called a meeting with Lieutenant Hargrove and the scout platoon. 12 snipers stood in a supply tent, rifles at their sides. Vinnie stood in the back, saying nothing. Hayes held up one of the modified rifles. This weapon has been altered in violation of army regulations.

Whoever is responsible for these modifications is subject to court marshall for destruction of government property. Silence. Hayes set the rifle down. However, these modifications have proven tactically effective. The casualty rate at this beach head has dropped 11% over the past 6 weeks. Artillery fire has decreased. Enemy spotters have been neutralized more efficiently.

He paused, looked at the snipers. I am ordering an engineering evaluation of these modifications. If the evaluation confirms they are safe and effective, I will recommend official adoption. Until then, any soldier caught modifying a weapon without authorization will face disciplinary action. He left.

The sniper stood there unsure whether they’d just been threatened or praised. Lieutenant Hargrove stayed behind. He walked to the back of the tent where Vinnie stood. Calibrazy. Sir, you started this. Sir, I don’t lie to me. I’m not an idiot. You’re the only sniper in this platoon with mechanical experience. You grew up fixing engines.

You modified your rifle and the others copied you. Vinnie said nothing. Harrove lowered his voice. I should court marshall you. But I won’t. You know why? No, sir. Because you saved lives. Reachi, Hooper, Garrett, Lynch. All those men died because we couldn’t kill spotters fast enough. You fixed that problem illegally, recklessly, but you fixed it. He stepped closer.

The engineering evaluation will take 6 weeks. If it comes back positive, you’ll be reassigned to a training unit to teach this technique. If it comes back negative, you’ll face court marshal. Understand? Yes, sir. Until then, keep your head down. Don’t modify any more rifles. Don’t teach anyone else.

And for God’s sake, don’t talk to any reporters. Yes, sir. Harrove left. Vinnie stood there alone in the tent. He’d just been told his future depended on whether Army engineers validated something he’d built in a supply tent at 2:00 a.m. The engineering evaluation took 9 weeks, not six.

A team from Aberdine Proving Ground arrived at Anio in late May and collected three modified rifles. They shipped them back to Maryland for testing. The engineers fired 500 rounds through each rifle. They measured gas pressure, bolt velocity, barrel stress, trigger timing. They disassembled the rifles and examined every component. They wrote a 47page report. The conclusion.

The gas operated modification increases rate of fire by approximately 300% without compromising accuracy or safety. Barrel life is reduced by an estimated 15% due to increased thermal stress. Trigger mechanism requires careful adjustment to prevent slam fires. Recommend controlled implementation with standardized manufacturing specifications.

The report sat on desks in Washington for 6 weeks. It was reviewed by the ordinance department, the infantry board, and the chief of staff’s office. Debates occurred. Some officers argued the modification violated the Springfield’s design philosophy. Others argued it saved lives. On August 12th, 1944, the War Department issued technical manual 91 1905A field modification of M1903 Springfield rifle for gas operated semi-automatic function. The manual included detailed instructions, diagrams, and tolerances.

It authorized trained armorers to perform the modification under supervision. The manual did not mention Vinnie Calabrace. It did not mention ANSIO. It attributed the modification to field observations and engineering analysis. By September 1944, 200 Springfield rifles had been converted using the official specifications. By November, the number was 800.

The rifles were deployed to sniper units in Italy, France, and the Pacific. The modification became standard for scout sniper teams operating in high casualty environments. The casualty rate among scout snipers dropped 14% compared to pre-modification rates.

Conservative estimates credited the gas operated Springfield with saving 340 American lives between August 1944 and May 1945. Vinnie Calibrazy received no official recognition, no medal, no commendation. His service record mentioned a reassignment to the infantry training center at Fort Benning, Georgia in October 1944. He spent 6 months teaching marksmanship and weapon maintenance.

He never mentioned the modification. When trainees asked about rapid fire techniques, he referred them to the technical manual. December 15th, 1944. Fort Benning, Georgia. Vinnie received orders to report to the Judge Advocate General’s office. He walked across the parade ground, Springfield slung over his shoulder, boots polished, uniform pressed.

Captain Morris, JAG officer, sat behind a desk covered in paperwork. He gestured to a chair. Sit down, Corporal. Vinnie sat. Morris opened a file. Corporal Vincent Calibrazy, service number 32158847. Scout sniper, Fifth Army, Anzio Beachhead. You modified a government rifle without authorization in March 1944. Yes, sir.

You understand that’s destruction of military property? Yes, sir. You drilled a hole in the barrel. You altered the trigger mechanism. You fabricated unauthorized components. Yes, sir. Morris closed the file. Why? Vinnie met his eyes. Men were dying, sir. German spotters were calling in artillery faster than we could kill them. Standard doctrine wasn’t working. I thought I could fix it.

And you didn’t ask permission? I knew what the answer would be. So, you violated regulations. Yes, sir. Morris leaned back in his chair. Your modification has been officially adopted. 800 rifles converted. 14% reduction in casualties. 340 lives saved. He paused. You should receive a medal. Vinnie said nothing. But you destroyed government property. You acted without authorization.

You encouraged other soldiers to do the same. Morris picked up a sheet of paper. The recommendation from Colonel Hayes is court marshal. Dishonorable discharge. 6 months confinement. Finn’s hands tightened on the arms of the chair. He said nothing. Morris set the paper down. However, the chief of staff’s office has reviewed your case.

They’ve decided that prosecution would create negative publicity. A soldier court marshaled for saving lives doesn’t play well in the press. He pulled out another sheet. You’re being reassigned to a rear echelon logistics unit. No combat duty, no training duty, no public recognition. You’ll serve out your enlistment processing supply requisitions in a warehouse. Sir, consider yourself lucky, Corporal.

You violated regulations and you’re walking away without a court marshal. That’s more than most soldiers get. I didn’t do this for recognition, sir. Then you won’t miss it. Morris stood. Dismissed. Vinnie left the office. He was reassigned to a supply depot in Virginia. He spent the next 7 months stamping forms and counting inventory. He never modified another rifle.

He never taught another class. The army buried him in paperwork and obscurity and he accepted it without complaint. The war ended in May 1945. Vinnie was discharged in August. He returned to Brooklyn with a duffel bag, a train ticket, and no ceremony. The gas operated Springfield modification remained in use through the end of World War II.

After the war, the army phased out the Springfield in favor of the M1 Garand, which was already semi-automatic. The modification became obsolete, but the principle didn’t. The idea that soldiers in the field could identify problems and innovate solutions became part of army doctrine.

The infantry board established a formal process for evaluating field modifications. The process still exists. In 1987, a military historian named Dr. Raymond Cook published a paper titled field innovation in the European theater. unauthorized modifications and tactical effectiveness. The paper included three paragraphs about the gas operated Springfield. It mentioned that the modification originated at Anio in March 1944.

It did not mention Vinnie Calibracy by name. The paper credited the innovation to an unidentified scout sniper from the fifth army. In 2003, a researcher at the Army Heritage and Education Center in Carile, Pennsylvania, discovered a maintenance log from Anio dated March 1944.

The log listed 12 rifles as nonregulation modifications, gas operation. One of the rifles was assigned to Corporal Vi Calibrazi, serial number 3215847. The researcher cross-referenced the name with service records. Found Vincent Calibrazi, Brooklyn, New York, found his discharge papers, found his death certificate from 1991.

The researcher wrote an article for Army History Journal. The article was titled The Silence Wave Shot: How a Brooklyn Mechanic Changed Sniper Doctrine at Anzio. It was published in 2004, 13 years after Vinnie died. Nobody in Vinnie’s family saw the article. His son had died in 1998. His daughter had moved to Florida and didn’t follow military history.

The article circulated among historians and veterans, but never reached the general public. The gas operated Springfield is now a footnote, a curiosity, a piece of military trivia. Most people have never heard of it. But between August 1944 and May 1945, that modification saved 340 American lives.

340 men who went home to Brooklyn, Kansas, Tennessee, Boston, and Memphis because a doc worker’s son from Red Hook decided that following regulations mattered less than keeping his friends alive. That’s how innovation happens in war. Not through committees, not through generals approving reports. Through corporals who work at 2:00 a.m. in supply tents drilling holes in rifle barrels, risking court marshal because they can’t watch one more man die.

Vinnie Calibracy never wanted recognition. He got none. His name appears in no official records of innovation, no metal citation, no training manual, just a maintenance log from Anzio. A researcher’s article published 13 years too late, and 340 men who lived long enough to go home.