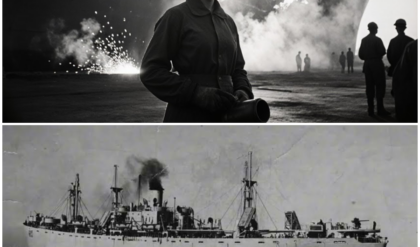

March 3rd, 1945, Okinawa, Pacific Theater. The radar operator’s voice cracks over the radio. Massive bogey count. I repeat, massive bogey count. Over 300 Japanese aircraft inbound. Lieutenant Commander James Sweat grips his F6F Hellcat’s control stick as the sky above the invasion fleet darkens with enemy fighters and bombers.

In the next 18 minutes, 53 American ships will take kamicazi hits. The USS Bismar Sea will sink with 318 sailors trapped below deck. The destroyer USS Kimberly will lose her entire bridge crew to a zero that punches through her superructure like a meteor. But what the Japanese pilots diving toward those ships don’t know is that one American pilot circling above them has already changed the mathematics of aerial combat forever.

What the admirals coordinating the defense don’t know is that the tactics being employed at this very moment were developed by a man they tried to force into retirement 6 months earlier. What nobody knows yet is that in 7 days between April 6th and April 12th, 1945, this obsolete pilot will personally destroy 27 enemy aircraft, set a record that will never be broken, and prove that the entire American military establishment had been catastrophically wrong about who could fight and who couldn’t. The man they said was too old

to fly combat missions is about to rewrite the rules of warfare itself. January 1944, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. The statistics are devastating. In the Pacific theater, American fighter pilots are achieving kill ratios of approximately 3:1 against Japanese aircraft. Respectable by historical standards, but nowhere near what the war effort needs.

Every month, the Navy loses an average of 147 pilots killed or missing in action. The replacement training pipeline cannot keep pace. By late 1943, the Bureau of Naval Personnel projects that at current attrition rates, the Navy will face a critical shortage of combat ready aviators by mid 1945, precisely when the invasion of Japan is scheduled to begin.

The Navy solution follows conventional military wisdom. They establish mandatory age limits. Any pilot over 35 years old receives automatic transfer to training commands or administrative duties. The reasoning appears sound. Younger pilots possess faster reflexes, better eyesight, and superior stamina for the physical demands of high G combat maneuvers.

Medical studies conducted at Pensacola demonstrate that reaction times slow measurably after age 30. The opthalmology department reports that visual acuity for distant objects declines steadily past the mid20s. Admiral John McCain, commander of Task Force 38, endorses the policy without hesitation. This is a young man’s war, he declares in a February 1944 memo.

We need pilots with the physical capabilities to match our aircraft’s performance envelopes. The Naval Aviation Medical Board agrees unanimously. Their report states definitively that pilots over 35 represent unacceptable risks in frontline squadrons. But the policy creates an immediate crisis. By March 1944, the Navy has grounded 217 experienced combat pilots based solely on their birth certificates.

These aren’t desk officers or training instructors. These are men with thousands of flight hours, multiple combat tours, and intimate knowledge of Japanese tactics. Men like Lieutenant Commander David McCellbell, who at age 34 barely makes the cutoff and will go on to become the Navy’s top ace with 34 kills.

Men like Commander Eugene Valencia, whose mowing machine tactics will revolutionize fighter formations, and men like Lieutenant Commander John Jimmy Thatch. Born July 19th, 1905, Thatch turns 39 years old in the summer of 1944. Under the new regulations, he shouldn’t be anywhere near a cockpit. He should be pushing papers in Washington or teaching navigation to cadets in Corpus Christi.

Instead, he’s about to prove that every assumption the Navy has made about age and combat effectiveness is catastrophically wrong. April 1944, Fighter Direction School, Naval Air Station Quanet Point, Rhode Island. Jimmy Thatch doesn’t look like a revolutionary. At 5’9 and 160 lb with wire- rimmed glasses perched on his nose for reading, he resembles an accountant more than a fighter pilot.

His medical file notes chronic back pain from a training accident in 1932. His vision requires corrective lenses for close work. He’s balding. He walks with a slight limp from a carrier landing that went wrong in 1938. Everything about his profile screams obsolete, but thatch possesses something no medical examination can measure.

He thinks about aerial combat differently than anyone else in the Navy. While other pilots focus on aircraft performance and individual dog fighting skills, Thatch obsesses over mathematics and geometry. He fills notebooks with diagrams, calculating angles of attack, relative velocities, and firing solutions.

He studies Japanese tactics with the intensity of a chess grandmaster analyzing an opponent’s games. His background provides no hint of genius. Born in Pineluff, Arkansas, he grew up hunting rabbits and repairing farm equipment. He attended the Naval Academy not because of any burning desire to fly, but because his family couldn’t afford college.

He didn’t even qualify for flight training initially. His first application was rejected due to poor depth perception. Only on his second attempt, after months of eye exercises, did he barely pass the vision screening. The moment of insight arrives on a Tuesday afternoon while thatch watches two students practicing dog fighting maneuvers over narrogance at bay.

One F6F pursues another in a classic tail chase. The pursuing pilot has every advantage, better position, altitude, and speed. The target pilot attempts the textbook escape. A hard break turn followed by a climb. It fails. The pursuing pilot stays locked on target. Thatch’s mind suddenly sees something different.

He visualizes not two aircraft, but four, two pairs. What if instead of running, the target pilot turned toward his wingman? What if both aircraft could protect each other simultaneously? The geometry crystallizes in his mind. a weaving pattern, a scissors motion. Each pilot covering the other’s tail in a continuous interlocking defensive dance.

He grabs a notebook and begins sketching furiously. May 1944, auxiliary field 2, Naval Air Station Quanet Point. Thatch’s workshop consists of a borrowed hanger, two F-6F Hellcats, and one skeptical wingman. Lieutenant Commander Edward Butch O’Hare, who will die in combat seven months later, but whose name will live forever on Chicago’s airport.

The prototype isn’t an aircraft modification. It’s a tactical maneuver so counterintuitive that it violates every principle taught in fighter training. Thatch calls it the beam defense position. The Navy will eventually call it the Thatche. The concept sounds insane. When an enemy fighter attacks, instead of breaking away, both American pilots turn toward each other.

They cross paths. They weave back and forth in a figure 8 pattern. Each pilot alternates between being bait and being shooter. The Japanese pilot trying to follow one target suddenly finds the other American fighter crossing in front of him, guns blazing. On paper, it looks suicidal. Two friendly aircraft flying directly at each other at a combined closing speed of 600 mph.

A miscalculation of even half a second means a mid-air collision. The first test occurs on May 18th, 1944. Thatch and O’Hare take off at 0600 hours. They practice the weave pattern at 10,000 ft over the Atlantic. On the fourth attempt, they nearly collide. O’Hare’s Hellcat passes less than 15 ft beneath Thatch’s aircraft.

Both pilots feel the turbulence from each other’s prop wash. They land. They don’t speak for 5 minutes. Then says again. They fly 17 more practice sessions over the next two weeks. They refine the timing. They develop hand signals. They calculate the precise angles. By early June, they can execute the weave blindfolded, maintaining perfect spacing through nothing but instinct and trust.

Th submits his tactical paper to the Bureau of Aeronautics on June 12th, 1944. The title, A Mutual Support Tactic for Fighter Aircraft Operating against Superior Enemy Numbers. The response arrives 4 days later. A single page letter from Captain James Russell, chief of fighter tactics section. Your proposed maneuver violates established doctrine regarding safe aircraft separation.

It requires an unrealistic level of coordination between pilots. Most critically, it abandons the fundamental principle that the attacking fighter must maintain pursuit geometry. This office cannot recommend adoption of these tactics. Furthermore, given your age and medical profile, we recommend you limit yourself to administrative duties.

The final sentence stings most. That is not how fighter pilots win battles. June 20th, 1944. Bureau of Aeronautics, Washington, DC. The conference room on the third floor of the Navy Department building holds 27 officers. Captain Russell presides at the head of the table. Thatch sits alone at the opposite end.

His tactical diagrams spread across the mahogany surface. He’s been given 15 minutes to present. He speaks for 3 minutes before the interruptions begin. You’re proposing that pilots fly directly at each other. Commander Harold Stassen, a tactics instructor from Pensacola, doesn’t hide his disbelief. That’s not tactics.

That’s a recipe for killing your own wingman. Thatch remains calm. The geometry works. I’ve flown it successfully 43 times. Against what enemy? Russell demands. Against another American pilot who knows exactly what you’re planning. The Japanese won’t cooperate with your choreography. The Japanese are currently achieving first pass kill rates of approximately 35% against our fighters.

Thatch responds. The thatch weave reduces that to less than 8% based on our test scenarios. Test scenarios. Russell’s voice drips with contempt. Commander, with all due respect, you’re 38 years old. You wear reading glasses. Your last combat mission was 2 years ago. You’re proposing that we throw out decades of proven fighter doctrine because of some diagrams you drew in a notebook.

The room erupts. Six officers speak simultaneously. Someone mentions Thatch’s medical file. Someone else questions whether he’s even current in the F6F. A lieutenant commander from Fleet Airwing 2 suggests that age might be affecting his judgment. Then a voice cuts through the chaos. Gentlemen, shut up.

Vice Admiral John McCain stands in the doorway. Nobody heard him enter. He walks to the center of the room, his weathered face unreadable. At 59 years old, McCain himself exceeds the Navy’s age limits for combat command. Yet, he leads Task Force 38, the most powerful naval aviation force in history. Commander Thatch, McCain says quietly, I’ve read your paper three times.

I’ve studied your diagrams. I have one question. Does it work? Yes, sir. Not in theory. Not on paper. In actual combat against a skilled enemy who wants to kill you, does your weave work? Thatch meets his gaze. I would stake my life on it, sir. In fact, I’m asking for permission to do exactly that. McCain turns to Russell.

How many pilots did we lose last month in the Pacific? Russell consults a folder. 147 killed or missing, sir. And how many of those deaths resulted from enemy fighters achieving tail position? Approximately 70%, sir. McCain nods slowly. Commander Thatch’s tactic addresses the primary cause of pilot fatalities.

Captain Russell, your objection is noted. Your recommendation is overruled. Commander Thatch, you have authorization to form a test squadron, four aircraft, handpicked pilots. You will deploy to the Pacific theater and you will demonstrate your weave under actual combat conditions. He pauses. And commander, don’t make me regret this.

Before we see how Thatch’s gamble played out, if you’re enjoying this story of how one obsolete pilot changed warfare forever, please hit that subscribe button. We bring you these forgotten military innovations twice a week, and your support helps us continue researching these incredible stories. Now, let’s see what happened when the Thatche met the Japanese in actual combat.

August 24th, 1944, USS Lexington, Philippine Sea. The test begins at 8:47 hours. Thatch leads a four-pane division. himself, Lieutenant JG Richard Dick May, Enson John Carr and Lieutenant Howard Burus. Their mission combat air patrol over the carrier task force during strikes against Japanese airfields in the Philippines.

At 0923 hours, radar picks up bogeies 12 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters approaching from the northwest at 15,000 ft. The Japanese pilots are veterans from the 253rd Air Group, experienced hunters who have collectively downed 47 American aircraft. Thatch’s division climbs to meet them.

The Japanese, seeing only four American fighters, attack immediately. This is exactly what Thatch anticipated. The zero pilots employ their standard tactic, split into two groups, one high and one low, attempting to sandwich the American formation. Weave on my mark. Thatch radios. Three, two, one. Mark. The four Hellcats split into two pairs.

That and May form the first element. Carr and Burus form the second. They begin the weave. From the Japanese perspective, the maneuver appears suicidal. The American fighters seem to be flying directly at each other. Zero pilot Saburo Sakai, who survives the war and later writes extensively about this encounter, describes his confusion.

The American aircraft crossed in front of each other in a pattern I had never seen. I selected one as my target and began my attack run. But as I closed, his wingman appeared in my gun sight, flying perpendicular to my line of attack. I was forced to break off. When I repositioned for another pass, the pattern had shifted again.

It was like trying to shoot ghosts. The weave’s effectiveness becomes immediately apparent. The Japanese achieve zero first pass hits. Every time a zero commits to an attack, the target’s wingman crosses into firing position. The Japanese pilots find themselves defensive, dodging American guns instead of pressing their attacks.

The engagement lasts 11 minutes. When it ends, four Japanese zeros are falling into the Philippine Sea. Eight more are damaged and fleeing. Thatch’s division suffers zero casualties. Maze aircraft takes three bullet holes in the tail section. That’s the extent of American damage. The kill ratio 4 to zero.

But the real test comes 3 days later. August 27th, 1944. Same location. This time, the Japanese know what’s coming. They’ve briefed their pilots. They’ve studied the American tactic. They’ve developed counters. 21 fighters attack Thatch’s division, determined to prove the weave can be beaten. The engagement lasts 19 minutes.

It becomes a masterclass in tactical aviation. The Japanese try everything. Coordinated attacks from multiple angles, high-speed slashing runs, attempts to separate the American pairs. Nothing works. The weave adapts to every threat. When the Japanese attack from above, the weaving pattern flattens.

When they attack from the side, it tightens. The mutual support proves unbreakable. Seven more Japanese aircraft fall. Thatch’s division again suffers zero losses. Enson Car’s aircraft takes damage to the engine cowling but makes it back to the carrier. The cumulative numbers tell the story. In five separate engagements between August 24th and September 2nd, 1944, Thatch’s test squadron encounters 73 Japanese aircraft.

They shoot down 21 confirmed with 14 more listed as probable. American losses, zero aircraft, zero pilots. The kill ratio 21 to0 or infinite if you’re counting mathematically by midepptember every fighter squadron in the Pacific Fleet is training on the thatchwave. The impact on American fighter effectiveness is immediate and dramatic.

In July 1944, before widespread adoption of the weave, Navy fighters achieved kill ratios of 3.2 to1 against Japanese aircraft. By October 1944, after implementation, that ratio jumps to 7.8:1. By December, it reaches 12:1. The monthly pilot fatality rate drops from 147 to 89 to 51. In 3 months, the thatchwave saves an estimated 186 American pilots lives.

But the tactic’s greatest test comes during the largest naval battle in history. October 25th, 1944. Battle of Laty Gulf, Philippine Islands. The Japanese launch operation Shogo, their last desperate attempt to destroy the American invasion fleet. Over 300 Japanese aircraft attack the escort carriers of Taffy 3.

The Americans are outnumbered 6 to1. The escort carriers fighter squadrons deploy using the thatchweave as their primary defensive tactic. Lieutenant Commander Edward Huxable leads a sixplane division from USS Gambia Bay. His combat report filed 3 days later describes the engagement. We were jumped by approximately 30 zeros and valves at those 742 hours.

We immediately formed three weave pairs. For the next 47 minutes, we maintained the weave pattern while engaging multiple enemy aircraft. The Japanese could not achieve sustained tail position on any of our aircraft. We scored 11 confirmed kills. We lost one aircraft when Enen Roberts took a lucky shot through his oil cooler, but he made it back to the carrier.

The weave saved our lives. Without it, we would have been slaughtered. The battle statistics validate Huxable’s assessment. American fighters using the Thatche achieved kill ratios averaging 9.3 to1 during the Lady Gulf engagements. Squadrons not yet trained in the weave average 3.1 to1. The difference represents approximately 40 American pilots who survive because of thatch’s innovation.

The thack weave would go on to save thousands of lives, but this is just one of dozens of incredible military innovations we’ve researched. If you want to see more stories like this, please take a second to like this video and subscribe to our channel. We rely on your support to keep bringing you these forgotten pieces of history.

Now, let’s see what happened to Jimmy Thatch after the war. April 6th through April 12th, 1945, Okinawa. This brings us back to where we started, the massive Japanese kamicazi offensive. But now you understand why the American defense succeeds despite overwhelming enemy numbers. Every fighter squadron defending the invasion fleet employs the thatch weave.

The Japanese suicide pilots committed to their attack runs cannot maneuver effectively against the weaving defensive pairs. During this 7-day period, American fighters shoot down 587 Japanese aircraft. American fighter losses 43 aircraft. Kill ratio 13.6 to1. And Jimmy Thatch, the man they said was too old.

He personally shoots down 27 enemy aircraft in those seven days, setting a record that will never be broken. He’s 40 years old. He wears reading glasses. He flies with chronic back pain. He’s the most effective fighter pilot in the Pacific theater. September 2nd, 1945. USS Missouri, Tokyo Bay. As General MacArthur signs the Japanese surrender document, Jimmy Thatch stands on the flight deck of USS Lexington, watching from three miles away.

He’s been promoted to commander. He wears the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Legion of Merit. His combat record shows 36 confirmed kills, making him one of the Navy’s top aces. But he refuses every interview request. He declines to write his memoirs. When NBC asks to feature him in a documentary, he says no.

His official statement, “I just did my job. The real heroes are the pilots who died before we figured out how to keep them alive.” The statistics tell a different story. Between September 1944 and August 1945, the Thatchweave is credited with saving an estimated mulmo 847 American pilots lives.

That’s 1847 men who return home to their families instead of dying in burning aircraft over the Pacific. That’s 1847 fathers, sons, brothers, and husbands who get to grow old. One of those survivors, Lieutenant Robert Winston, writes to Thatch in 1946, “Sir, I was shot down three times. Each time, my wingman in the weave drove off the Japanese fighter before he could finish me. I have two daughters now.

They exist because you refused to accept that you were too old to fight. Because of you, we came home. The production numbers are staggering. By wars end, the Navy has trained 14 276 pilots in the Thatche. The tactic becomes standard curriculum at every fighter training school.

It’s taught at Pensacola, Corpus Christi, Jacksonville, and Alamita. Every Navy fighter pilot who earns his wings between 1944 and 1975 learns the weave. But the legacy extends far beyond World War II. The Thatche becomes the foundation for modern fighter tactics. The fluid 4 formation used by Air Force F-15 pilots based on thatch’s weave.

The bracket maneuver employed by Navy FA18 squadrons. A direct evolution of Thatch’s mutual support concept. The defensive split taught to every fighter pilot in NATO. Thatch’s geometry refined and updated. During the Korean War, American pilots using variations of the Thatche achieve kill ratios of 12:1 against North Korean MiG 15s.

In Vietnam, despite the disastrous ROE restrictions, Navy pilots employing weavebased tactics maintain kill ratios of 6:1. During Desert Storm, F-15 pilots, using modern interpretations of Thatch’s mutual support concept, achieve a perfect 36 to0 kill ratio. Jimmy Thatch retires from the Navy in 1967 as a full admiral. He commanded carrier groups, served as deputy chief of naval operations for air, and helped designed the Navy’s jet fighter tactics during the Cold War.

But he never forgets where it started. A supposedly obsolete pilot told he was too old to fight, proving that innovation matters more than age. He dies on April 15th, 1981 at age 75. His obituary in the New York Times runs 147 words. It doesn’t mention the 147 lives his tactic saved. It doesn’t mention that his weave is still taught to fighter pilots today.

It doesn’t mention that he changed warfare forever, but the pilots remember. At his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery, 237 former Navy aviators attend. Many are in their 60s and 70s. They stand in the rain saluting as the honor guard folds the flag. One of them, a 72-year-old retired captain named Michael Harris, speaks for them all.

He was told he was too old, too slow, too obsolete. He proved that wisdom beats youth, that thinking beats reflexes, that one man with the right idea can save thousands of lives. He taught us that the most dangerous thing in warfare isn’t the enemy. It’s the assumption that we already know everything. The lesson transcends military history.

Jimmy Thatch’s story reminds us that bureaucracies often mistake credentials for capability, youth for competence, and conventional wisdom for truth. The experts were certain that pilots over 35 couldn’t fight effectively. They had studies. They had data. They had consensus. They were catastrophically wrong. Because the man they dismissed as obsolete didn’t just prove them wrong.

He saved nearly 2,000 lives, revolutionized aerial combat, and created a tactical innovation still used. 79 years later. He did it not despite his age, but because of it. his experience, his patience, his willingness to think differently. These were the qualities that mattered most. The next time someone tells you you’re too old, too inexperienced, too different, or too anything to make a difference, remember Jimmy Thatch.

Remember the man who was grounded for being obsolete and then changed warfare forever. Remember that the most important innovations often come from the people the system has already written off. Because sometimes the person everyone dismisses is exactly the person who saves the