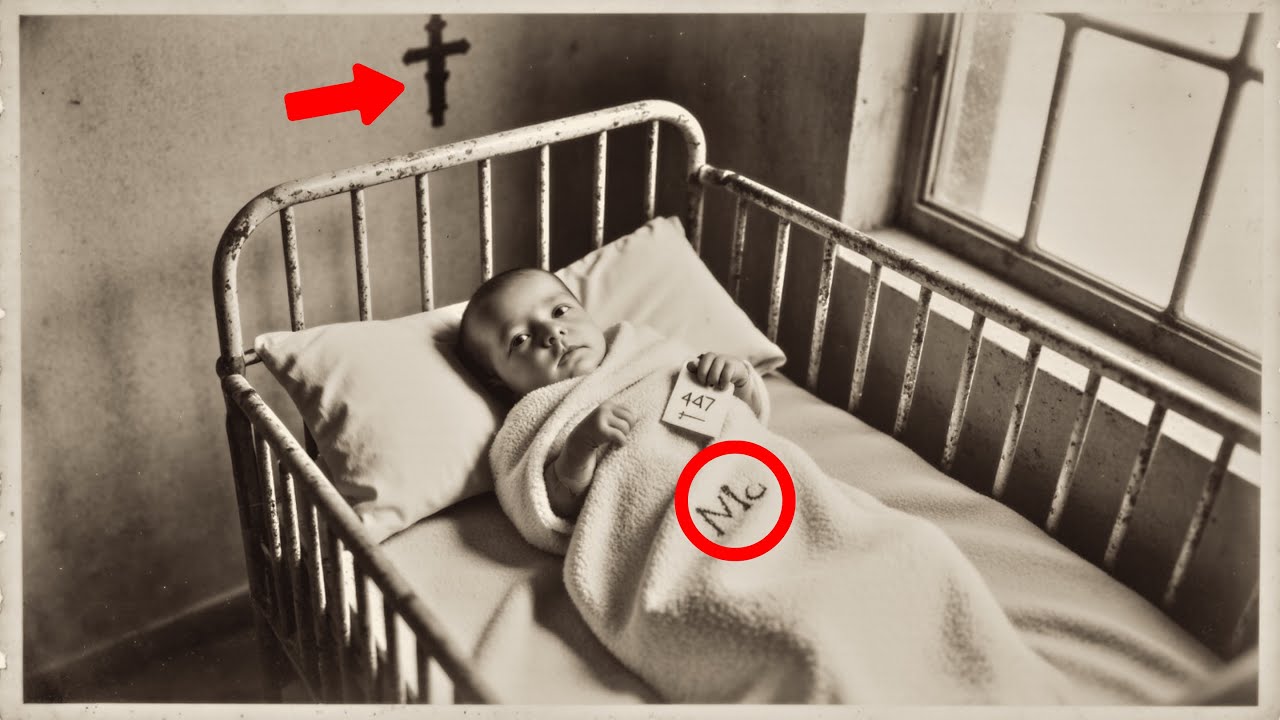

What if a single photograph was the only clue to a life lived under the wrong name? In February of 1923, inside St. Mary’s orphanage in Boston, a baby was left behind with nothing but a blanket embroidered with the initials Mo and a false entry in the orphanage ledger.

But decades later, when that photograph resurfaced during the demolition of the orphanage, something hidden in the child’s tiny fist raised a question that would haunt three generations. What was really kept secret that winter morning? And why did it take more than 70 years to surface? Stay with me because I’m going to tell you the complete dramatized story inspired by real historical events.

Before we begin, make sure to subscribe, hit the like button, and tell me in the comments which city you’re watching from. Your support keeps these dramatized stories alive and helps us bring forward forgotten fragments of history with lessons that still matter today. This photograph captured a moment that would haunt three generations. February 14th, 1923, St. Mary’s orphanage, Boston.

A baby wrapped in a blanket embroidered with the initials M O. But the name in the orphanage ledger read John Francis. Entry number 447. If you stay until the end, you’ll discover why this child grew up to touch hundreds of lives without ever knowing his mother died whispering his real name.

This is the story of how a single photograph revealed the most devastating secret a mother could carry to her grave. The photo was discovered 70 years later, tucked inside a wall during the orphanage demolition. But look closely at the baby’s tiny fist. He’s clutching something. something the nuns tried desperately to hide, something that would have changed everything if anyone had noticed.

The photographer, an elderly Italian man named Juspe Romano, would later write in his diary that he heard a woman crying outside the orphanage that very morning. A woman who stood in the February snow for 3 hours, staring at a window she couldn’t reach. This is Margaret O’Conor, 19 years old, standing outside St. Mary’s at dawn. The nuns admission records from 1923 confirmed she arrived at 5:47 a.m. with a bundle in her arms.

She had walked 7 mi through a blizzard from the Lel Mills factory dormitories. Her roommate, Annie Sullivan, would later testify that Margaret’s fingers were so frostbitten she couldn’t feel the baby anymore. But Margaret was hiding something even the nuns didn’t know.

She had sewn $3 into the lining of the blanket, her entire month’s wages, with a note that read, “For when he asks about me.” Because on that morning, February 14th, Valentine’s Day, Margaret O’Connor had exactly 4 hours and 13 minutes left with her son. The factory whistle would blow at 10:00 a.m. If she wasn’t at her station, her father would know.

and her father, Patrick O’Connor, had already broken her ribs once when he discovered she was pregnant. She could still taste blood when she coughed. The admission ledger shows Margaret signed her baby away at 6:15 a.m. But what it doesn’t show is that she stood at the orphanage gate until 9:45, watching the window where she thought her baby might be. Sister Catherine, the head nun, had seen this before.

Young Irish girls destroying their lives for men who vanished like smoke. She took the baby with the efficiency of someone handling freight. Entry number 447. Another mouth to feed. Another soul to save. But Sister Agnes, just 22 herself, noticed something the older nun missed. The baby wasn’t crying.

In her diary discovered after her death in 1978, Agnes wrote, “The child looked at me with eyes that seemed to already know he’d been abandoned, as if he decided crying was pointless before he could even speak. Margaret had named him Michael, Michael James O’Conor. She had whispered it to him every night for 9 months, her hand on her belly while she worked 18-our shifts at the textile mill. But that name died the moment she walked through the orphanage doors.

The nuns had a system. Boys were John, Thomas, or Patrick. Girls were Mary, Catherine, or Anne. Simple, forgettable, easy to track. John Francis, they wrote, “Baby number 447, fed at 7:00 a.m., changed at 8:00 a.m., forgotten by 9.” But to understand how this baby survived what killed 12 other infants that same winter, we need to go back 6 months to the night Margaret O’ Conor discovered she was pregnant in a factory bathroom stall, biting her own hand to keep from screaming. August 15th, 1922. The feast of the assumption. The night

she realized her life as she knew it was over. Margaret had been saving for 3 years to become a teacher. Every penny she didn’t spend on food went into a jar hidden behind a loose brick in the dormatory wall. She had taught herself to read using newspapers she found in the factory trash. Her dream was simple.

Escape the mills, learn properly, teach others. But Thomas Brennan, the foreman’s son, had other plans. He promised marriage. He promised escape. He promised everything except the truth. He was already engaged to a merchant’s daughter from Worcester. The night she told him about the baby, he laughed. Actually laughed. Then he offered her $10 to take care of it.

When she refused, he had her transferred to the night shift where pregnant women often miscarried from the machinery vibrations and chemical fumes. But Margaret wrapped her belly with three layers of cloth every night, so tight she could barely breathe. She was determined this baby would live even if it killed her.

Her father found out on Christmas Eve 1922. Her younger sister, Bridget, jealous of the attention Margaret was getting from their mother, told him about the hidden pregnancy. Patrick O’Connor was a man who had survived the Irish famine as a child by eating grass. He didn’t believe in mercy.

He dragged Margaret into the snow behind their tenement and beat her until she couldn’t stand. Her mother, too. who terrified to intervene, could only watch from the window. The beating was so severe that Margaret went into early labor. But somehow, impossibly, the baby held on. Dr.

James Murphy, the only Irish doctor in Boston who would treat unmarried mothers, delivered the baby on February 12th, 1923. His medical records preserved in the Massachusetts Historical Society note. Premature male infant, approximately 5 lbs, strong lungs despite circumstances, mother hemorrhaging severely. Survival of either uncertain, but both survived.

For exactly 2 days, Margaret held her son in a charity ward bed, whispering stories about the Ireland she’d never seen, singing lullabies her grandmother had taught her. The decision to give him up wasn’t really a decision at all. Her father had made it clear. come home without the baby or don’t come home at all. She had no money for rent, no family who would take her in.

The factory had already replaced her. She could keep her baby and watch him starve on the streets or give him to the nuns and pray he’d have a chance. On the morning of February 14th, she made her choice. 1923, Boston, where Irish mothers learned to swallow their screams and orphanages overflowed with secrets. The St.

Mary’s admission ledger for that year shows 312 babies admitted. By December, 47 had died. But baby number 4047, the child they called John Francis, had something the others didn’t. He had Sister Agnes secretly singing him Irish lullabibis when Sister Catherine wasn’t watching. And he had Juspe Romano, the orphanage janitor, carving him tiny wooden horses from discarded church pews.

These small acts of love would be the difference between another unmarked grave and a life that would touch hundreds. Margaret O’Connor returned to the factory that same morning, February 14th. Her supervisor noted in the work log that she was 15 minutes late and her hands were shaking so badly she couldn’t thread the looms.

Annie Sullivan, her roommate, found her that night standing on the mill bridge, looking down at the frozen river below. Margaret whispered. I can still hear him crying. Annie grabbed her arms and pulled her back. For the next two weeks, Annie would sleep across the doorway to keep Margaret from leaving in the night.

Back at Saint Mary’s baby, John Francis was dying. The orphanage doctor’s notes from February 20th read, “Infant refusing bottle. Weight loss critical. Unusual for abandoned infants to survive rejection trauma beyond first week. But Sister Agnes had noticed something the doctor missed. The baby only cried when held by certain people with her.

He was quiet, almost peaceful. She began breaking the rules, taking him from the nursery at night, holding him while she prayed. If Sister Catherine had discovered this, Agnes would have been sent back to Ireland in disgrace. The photographs from this period preserved in the Boston Arch Dascese archives show rows of iron cribs each exactly 18 in apart. Efficiency was everything.

Love was dangerous. It made you weak. It made you question God’s plan. Sister Catherine had learned this lesson 40 years ago when she first took her vows. But Agnes was young. She still believed that God’s love could work through human hands.

She would sneak extra milk to Jon’s bottle, adding a precious spoonful of honey when he wouldn’t eat. Meanwhile, Margaret was writing letters she could never send. 73 letters over 4 years, all addressed to my little Mo. Her sister Bridget would find them after Margaret’s death, hidden inside a flower sack beneath her bed.

The first letter dated February 20th, 1923 reads, “My darling boy, today you are one week old. I wonder if your eyes are still blue. I wonder if you still have that tiny birthark on your left shoulder that looks like a crescent moon. I wonder if you know that your mother thinks of you every second of every minute of every hour.

But Margaret had bigger problems than heartbreak. The factory had begun laying off workers. The economy was turning. Her father had started drinking more, spending what little money the family had at Murphy’s Tavern. Her mother, Ellen Okconor, was showing signs of consumption, coughing blood into handkerchiefs she tried to hide. The family needed Margaret’s wages desperately. But Margaret could barely function.

She had started making mistakes at the looms. Dangerous mistakes that could cost fingers or worse. March 3rd, 1923. The orphanage received its first adoption inquiry for baby John Francis, a wealthy Protestant couple from Beacon Hill. Unable to have children of their own, they wanted a healthy white infant, no deformities, no Irish.

When they learned John’s background, they walked away. The second inquiry came two weeks later. A Catholic family from Souy, doc workers with eight children already. They wanted a baby who wouldn’t cry too much. Jon cried for 3 hours straight during their visit. They chose a quieter baby instead. By April, Jon had developed a chronic cough. The orphanage was damp, cold, and overcrowded.

The Boston Health Department inspection report from that month noted inadequate heating, water damage, and nursery concerning infant mortality rate. But there was nowhere else for these babies to go. Sister Agnes began sleeping in a chair next to Jon’s crib, worried he would stop breathing in the night.

She would place her hand on his tiny chest, feeling for the rise and fall, praying rosaries until dawn. The third adoption attempt came in May. An Irish couple, the Kelly’s, who had lost their own infant to scarlet fever. “The wife, Patricia Kelly, held Jon and began crying.” “He looks like our Timothy,” she whispered. They were about to sign the papers when Mr. Kelly lost his job at the shipyard.

They couldn’t afford another mouth to feed. Patricia Kelly kissed Jon’s forehead before leaving and pressed a silver medallion of St. Christopher into Sister Agnes’s hand. For his protection, she said. Joseeppe Romano, the janitor, had been watching all of this from the shadows. An immigrant from Sicily, he had lost his own family in the 1918 influenza pandemic.

In his diary, he wrote, “The baby with the sad eyes reminds me of my Antonio. I leave him wooden toys when the nuns aren’t looking.” Today, he smiled. First time I’ve seen him smile. Jeppe had been at the orphanage for 5 years, invisible to most, but seeing everything. He knew which nuns hit the children. He knew which ones snuck them extra food.

He knew Sister Agnes loved Baby Jon like her own. June 1923, Margaret attempted suicide for the first time. She drank a bottle of cleaning fluid she stole from the factory. Annie Sullivan found her convulsing on the dormatory floor and forced milk down her throat until she vomited. The incident was covered up.

Mental weakness was grounds for immediate dismissal. But Annie knew Margaret was breaking. She had stopped eating. She had stopped talking about her teaching dreams. She only spoke about the baby, wondering if he was warm enough, if he was being held, if he knew he was loved. At the orphanage, Jon had survived his first major crisis, a pneumonia outbreak that killed three infants in July.

Sister Agnes had wrapped him in her own wool blanket, the one her mother had made for her when she left Ireland. She sat up with him for four nights straight, spooning water into his mouth when he was too weak to drink. Sister Catherine found her collapsed on the floor on the fifth morning. Jon still breathing in her arms.

Instead of punishment, Catherine said nothing. Sometimes even the hardest hearts crack a little. September 1923. John had been rejected by three families, survived pneumonia, and developed a persistent cough that made him sound like an old man. But something had changed in his eyes. Sister Agnes noted in her diary, “The child no longer cries for comfort.

He cries only when hungry or soiled. It’s as if he’s learned that tears for love are wasted.” He was 7 months old and had already learned the orphanage’s hardest lesson. Expect nothing. Survive everything. Then came the Brennan. Thomas and Mary Brennan from Worcester, Massachusetts. Not the wealthy Brennan from Beacon Hill, but workingclass Irish who ran a small grocery store near Shrewsbury Street.

They had been married 12 years without children. The shame of it was killing Mary Brennan slowly, whispered about at church, pied at family gatherings. Her husband, Thomas, was a functional alcoholic who hid his whiskey bottles in the store’s basement. But he was gentle, never violent, just sad in a way that Irish men weren’t supposed to be. October 2nd, 1923.

The Brennan’s visited St. Mary’s for the first time. Mary Brennan later wrote in a letter to her sister. I saw him across the room coughing in his crib, ignored while prettier babies were shown to other couples. Something in his eyes looked like Tommy’s after the war, lost but still fighting.

When she picked him up, Jon didn’t cry. He studied her face with those serious blue eyes, then grabbed her finger with surprising strength. Thomas Brennan, three whisies deep already that morning, started crying. “He’s got a fighter’s grip,” he said. But the adoption wasn’t simple. The Brennan were poor, borderline destitute by the state standards.

Thomas’s drinking was known to the parish priest. Mary had health problems, mysterious pains that kept her bedridden some days. The orphanage preferred to place children with more stable families. Sister Catherine was ready to reject their application when Sister Agnes intervened. She lied. Told Catherine that the Brennons were more financially stable than they appeared.

Showed falsified bank statements that Jeppe had helped her create. It was the first time Agnes had ever deliberately sinned for someone else. Meanwhile, Margaret O’Conor was dying, though she didn’t know it yet. The persistent cough that had started in August was tuberculosis. The facto’s cotton dust had destroyed her lungs, and the beating from her father had weakened her past recovery.

Doctor Murphy’s medical notes from October 1923 state, “Patient presenting with hemoptsis night sweat, severe weight loss, prognosis poor, estimated 6 to 12 months if confined to sanatorium without treatment, 3 to 4 months maximum.” But Margaret couldn’t afford a sanatorium. She couldn’t even afford to miss a day of work.

She had started coughing blood into rags she burned each night. Her family needed her wages. Her mother was also sick now, bedridden, praying rosaries for a miracle that wouldn’t come. Margaret’s letters to her unseen son became more desperate. My darling Mo, I fear I won’t live to see you grow. But know this, you were loved. You were wanted. You were the only pure thing in my ruined life.

November 15th, 1923. The day that almost changed everything. Margaret was assigned to clean the St. Joseph’s Hospital charity ward. The hospital occasionally hired factory girls for extra cleaning when their regular staff was overwhelmed. She needed the money desperately. Her father had been fired for fighting and the family was 3 weeks behind on rent.

She accepted immediately, not knowing that St. Joseph’s had just admitted several children from St. Mary’s orphanage for treatment. Jon was there in bed number 12, being treated for his persistent respiratory infection. Margaret walked into the ward carrying her mop and bucket and froze. Even from across the room, she knew the shape of his head.

The way his hair grew in a little swirl at the crown, the birthark on his shoulder, visible where his gown had slipped. Her son, her Michael, alive, still fighting. She stood paralyzed in the doorway for so long that a nurse had to ask if she was feeling faint. For 2 hours, Margaret mopped the same corner of floor, watching him sleep. She memorized every detail.

He was thin, too thin, but his color was good. His breathing was labored but steady. He had her father’s nose, unfortunately, but her mother’s delicate mouth. She wanted to run to him to hold him, to tell him who she was, but she knew what would happen. They would throw her out.

They might hurt him somehow, punish him for having a mother who couldn’t keep him. So, she watched and she planned. At 300 p.m., the ward nurse took her break. Margaret had 15 minutes. She walked to Jon’s bed on legs that felt like water. Up close, she could see he was awake, those blue eyes staring at nothing.

She reached out one shaking hand and touched his cheek. He turned toward her touch, instinctively seeking warmth. “Michael,” she whispered. “My beautiful Michael James.” He looked at her without recognition, of course. He was 9 months old. He didn’t know her voice anymore. But he smiled, a small, tentative smile that destroyed what was left of her heart. She heard footsteps in the corridor, the nurse returning early.

Margaret pulled out the medallion she wore, a cheap tin sacred heart her grandmother had given her. She kissed it and tucked it under his pillow. For protection, she whispered, “Until I can come for you.” Then she grabbed her bucket and moved to the next ward, her body on autopilot while her mind screamed. She would come back. She would find a way.

She would reclaim her son, even if it killed her. But when her shift ended and she returned to bed 12, Jon was gone. Discharged back to the orphanage an hour after she left. The medallion was gone, too. Thrown away by a nurse who thought it was trash. Margaret searched the garbage bins until security forced her to leave.

She walked home in the November cold, planning she would get better. She would save money. She would marry someone respectable and come back for him as a proper married woman. She had time. He was still a baby.

Who would want a sickly orphan with a bad cough? The next morning, November 16th, the Brennan finalized J’s adoption. The papers were signed at 9:15 a.m. By 10:00 a.m., John Francis was in a wagon heading to Worcester, wrapped in Mary Brennan’s own coat, leaving Boston forever. Margaret wouldn’t learn about the adoption for three more months.

By then, she would be too sick to stand, coughing blood into basins while writing her final letters to a son who now had a different name, a different family, a different future. February 14th, 1924, exactly 1 year after Margaret gave up her baby, she was dying now, confined to her bed, too weak to walk. Her weight had dropped to 78 lb. Dr. Murphy’s notes read, “Patient in final stages, days, not weeks.

” But Margaret had one last mission. She had learned about the adoption through a factory friend who knew someone at St. Mary’s. Her son was alive. He had a family. He had a chance. But she needed to see proof. She needed to know he was loved. Annie Sullivan, ever loyal, went to Worcester. She found the Brennan grocery store on Shrewberry Street, a narrow building squeezed between a butcher shop and a cobbler.

Through the window, she saw Mary Brennan holding a baby, feeding him mashed potatoes with infinite patience while he grabbed at the spoon. The baby was laughing, actually laughing. Annie watched for an hour, memorizing every detail to report back to Margaret. The child was clean, well-dressed in a hand knitted sweater, and clearly adored.

Back in Boston, Margaret received the news with tears that wouldn’t stop. He laughed. She kept asking. “You sure he laughed?” Annie nodded, holding Margaret’s skeletal hand. That night, Margaret wrote her final letter. “My darling Mo, you have a mother now who can feed you properly. Hold you without shame. Love you in daylight. Be good for her. Be the son I couldn’t let you be.

But know that somewhere your first mother loved you enough to break her own heart so yours could be whole. The photograph that would haunt three generations was taken on February 20th, 1924. Not at the orphanage, but at the Brennan home.

Thomas Brennan had borrowed a camera from a customer who owed him money. He wanted to document their son’s first birthday with them. Even though Jon’s actual birthday was unknown, Mary had made a small cake with their rationed sugar. John, now walking on unsteady legs, had cake on his face and hands. In the photograph, he’s reaching for Mary while Thomas holds him.

All three are smiling. It’s the first documented moment of Jon being truly happy. But look closer at that photograph. In the background, barely visible, is a woman standing across the street. A thin figure in a dark coat too far away to identify clearly. Jeppe Romano, who had remained in contact with Sister Agnes, would later swear he saw Margaret O’Connor in Worcester that day, though she was supposedly bedridden in Boston. How a woman that sick could have made the journey remains a mystery.

Annie Sullivan always denied taking her, but admitted years later that Margaret had disappeared for 6 hours that day, March 1st, 1924. Margaret O’ Conor died at 4:47 a.m. Her last words, according to her sister, Bridget, were, “Tell him his name is Michael.” But Bridget, still resentful of the attention Margaret had received, told no one.

She burned the 73 letters, keeping only one that she hid in her own daughter’s baby book. That daughter would be Mary O’ Connor, who would one day, unknowingly, be taught to read by her own cousin. The Brennan, meanwhile, were discovering that their son was exceptional.

Despite his rough start and persistent health issues, Jon had an incredible memory. By age two, he was recognizing letters. By three, he was reading simple words. By four, he had taught himself to read by studying the labels in his parents’ grocery store and listening to Mary read the Bible each night. His stutter was severe, worse when he was nervous.

But when he read aloud, it disappeared. Words on a page were safer than words in his mouth. One, John started school at St. Peter’s Catholic School in Worcester, his first grade teacher, Mrs. Sullivan, wrote on his report card. Jon is brilliant, but withdrawn. He seems afraid other children will disappear if he gets too close. Recommends additional attention to social development. What Mrs.

Sullivan didn’t know was that Jon had started having nightmares. Dreams of a woman crying outside his window. Dreams of being underwater, unable to breathe, reaching for someone who wasn’t there. Thomas Brennan’s drinking had worsened. The grocery store was failing. The depression was coming, though no one knew it yet.

But he never raised a hand to John or Mary. Instead, he would sit in the basement among his whiskey bottles and cry. John would sometimes find him there and sit quietly beside him, neither speaking, both understanding something broken in the other. Mary held them all together with fierce determination and patches upon patches on their clothes. One, John was nine.

His teacher, Sister Margaret, noticed him helping younger students with their reading. He had infinite patience with the slowest learners, never mocking, never frustrated. When she asked him why, he said, “Someone was patient with me once. I don’t remember who, but I remember the feeling.” Sister Margaret would later write in her teaching journal that she had never seen a child with such natural teaching ability.

But Jon’s health remained fragile. His lungs damaged from those early months in the damp orphanage would never fully recover. He caught every cold, every flu. In 1933, he nearly died from pneumonia. Thomas Brennan, drunk and desperate, prayed for the first time since the war. Mary Brennan sold her mother’s wedding ring to pay for medicine.

Jon survived, but the illness left him even more fragile. The doctor recommended he avoid physical labor. His future would have to be behind a desk, not in a factory or field. One the moment that almost revealed everything. John, now 18, needed his birth certificate to enlist after Pearl Harbor. He returned to St.

Mary’s orphanage, now nearly empty as the state had started closing such institutions. Sister Agnes, still there after all these years, now in her 40s, met him at the door. The moment she saw his face, she knew he looked exactly like Margaret O’Conor. the same eyes, the same determined chin, the same way of tilting his head when thinking. She led him to the records room, her hands shaking. She pulled out his file.

Inside was everything. The original admission form with Margaret’s name blacked out, but still visible if you held it to the light. The receipt for $3 that had been found sewn into a blanket. A note in Sister Catherine’s handwriting. Mother, Irish, factory worker, unwed. Father, unknown, child to be given neutral name for best adoption chances.

And at the bottom, in Agnes’ own young handwriting, baby cries less when held, responds to Irish lullabies. Agnes stood there holding his history in her hands. She could tell him everything. She could give him his mother’s name, tell him about the letters she knew existed, tell him he had been loved desperately.

But she looked at his face, saw peace there despite everything, saw a young man ready to serve his country, and made a choice. She pulled out only the official birth certificate. John Francis, parents unknown, ward of the state. The rest she slid back into the file. Some truths, she decided, were too heavy for one heart to carry.

Jon didn’t enlist after all. His damaged lungs failed the physical examination. While other young men marched off to war, he was rejected. Classified 4F, unfit for service. The shame of it nearly broke him. But Mary Brennan, now graying and bent from years of hard work, told him, “God saved you for something else. Teaching is your battlefield.

” So John enrolled in Worcester State Teachers College on a scholarship for wounded children of veterans. Thomas Brennan, having served briefly in World War I before his drinking began. One John’s first teaching position, a one- room schoolhouse in rural Spencer, Massachusetts. 22 students, ages 6 to 14, mostly children of Polish and Italian immigrants.

His starting salary was $18 a month. He lived in a room above the general store, coughing through the nights, preparing lessons by candle light. But in that classroom, his stutter disappeared entirely. When he taught, he became someone else, someone confident, someone whole. Among his students was Mary O’ Connor, age seven, Bridget’s daughter, his own cousin, though neither knew it.

Mary had the same green eyes as Margaret, the same determined chin, the same way of biting her lip when concentrating. Jon felt drawn to her immediately, inexplicably. She struggled with reading, mixing up letters, crying from frustration. He stayed after school every day for 3 months, teaching her patiently, never charging her struggling family a penny.

Years later, Mary O’ Connor would write in her college application essay. Mr. Brennan taught me that words were doors, not walls. He said everyone deserved to walk through them. He had a stutter when he talked, but not when he read aloud. He showed me that we all have different voices and they’re all worth hearing.

She became the first Okconor woman to graduate from college. She became a teacher. The dream Margaret never got to live. One, the war ended. Thomas Brennan died of liver failure, leaving Mary Brennan widowed and the grocery store bankrupt. Jon moved back to Worcester to care for her. He taught at St. Peters, the same school where he had learned to read.

His students remember him as strict but kind, demanding but patient. He never raised his voice. He never gave up on anyone. He kept a box of sandwiches in his desk for students who came to school hungry. One student, Roberto Silva, son of Portuguese immigrants, wrote years later, “Mr. Brennan, saw me stealing food from other kids’ lunches. Instead of reporting me, he started forgetting his own lunch every day, asking if I could share mine.

Then he’d give me most of his sandwich, saying he wasn’t very hungry. He did this for an entire year. I became a teacher because of him. 30 years later, I do the same thing for my hungry students. One, John met Patricia Murphy, a nurse at St. Joseph’s Hospital, where he was being treated for yet another bout of pneumonia.

She was plain, practical, and had been told she could never have children due to a childhood illness. They married in 1951. a quiet ceremony with only Mary Brennan and a few friends attending. Patricia understood his silences, his nightmares, his need to check on her constantly as if she might disappear. They adopted a daughter in 1953, a girl abandoned at the same St.

Mary’s orphanage where Jon had spent his first year. They named her Agnes. One Sister Agnes, now elderly and dying, sent Jon a package. Inside was the wooden horse Juspe Romano had carved for him, saved all these years. Also, a photograph of a young woman standing outside the orphanage in the snow, barely visible through the windows frost on the back in Agnes’s shaking handwriting. She stood there every Sunday for 3 months after you left.

I thought you should know someone mourned for you. She didn’t sign it. She didn’t name the woman, but Jon stared at that blurred figure and felt something shift in his chest. Two. Jon had taught over 2,000 students. His lungs were failing worse each year. He retired at 47, too sick to continue. At his retirement ceremony, the auditorium was packed.

Students from three decades came. Mary O’ Connor, now a principal herself, spoke about the teacher who changed her life. Roberto Silva, now teaching in Boston, brought his entire class. Even Josephe Romano, 93 years old, came from the nursing home carrying a new wooden horse he had carved with arthritic hands. During the ceremony, an elderly woman approached Patricia Brennan.

She introduced herself as Annie Sullivan, said she had known Jon’s birthother. Patricia, protective and suspicious, asked what she wanted. Annie pressed an envelope into her hand. He should have this when he’s ready, she said. Then disappeared into the crowd. Inside was one letter, the only one Bridget hadn’t burned.

The one that said, “Be good for her. Be the son I couldn’t let you be.” One, Sister Agnes died. In her will she left Jon her diary. Reading it, he learned about the Irish lullabies, the nights she held him, the lies she told to get him adopted. He learned that he had been loved by strangers who risked everything to keep him alive.

He learned that the Brennan had wanted him desperately, that his adoption was not charity but choice. He learned that love comes in many forms, not all of them visible. Two, John began writing his memoirs for his grandchildren. He titled it Names We Carry. In the introduction, he wrote, “I was born with one name, raised with another, but the name that matters is the one written in the hearts of those we touch.

My mother named me John Francis, but my students called me Hope. That’s the name I choose to claim.” Three. John Francis Brennan died on March 1st, exactly 69 years after Margaret O’ Conor. His funeral filled three churches. Students, colleagues, children he had taught to read, adults he had inspired to teach. Mary O’ Connor gave the eulogy. She revealed then what she had discovered years earlier through genealogy research. They were cousins.

Jon had unknowingly fulfilled his birth mother’s dying wish, teaching an Okconor woman to read and write, to escape the factories to live the dream Margaret couldn’t. In his coffin, Jon held three things. the photograph from the orphanage showing him as baby 4047, the wooden horse Jeppe had carved, and a letter from one of his students that read, “You taught me that everyone deserves a second chance at a first impression. Thank you for being my second chance.” The orphanage was demolished in 1994.

During the demolition, workers found a blanket wedged behind a wall preserved by accident, embroidered with the initials MO. It still had $3 sewn into the lining and a note so faded it was barely readable for when he asks about me. The blanket was donated to the Worcester Historical Museum labeled Unknown Providence circa 1920s.

No one connected it to John Brennan, the teacher who had changed thousands of lives. But perhaps that’s the point. John never knew his birth name was Michael James Okconor. He never knew his mother died whispering his real name. He never knew she stood in the snow watching his window.

He never knew about the 73 letters or the failed suicide attempts or the fact that she saw him one last time in Worcester, watching from across the street as he celebrated his first birthday with his new family. What John did know was this. Every child deserves someone who believes they can learn. Every person who stutters has something worth saying.

Every abandoned soul can become someone’s salvation. He lived his entire life not knowing where he came from, but he spent every day making sure others knew where they could go. The photograph from 1923 still exists in a museum archive in Boston. If you look closely, you can see something in that baby’s tiny fist.

It’s not visible enough to identify, but Sister Agnes’ diary reveals what it was. A thread from Margaret’s shawl that he had grabbed as she handed him over and wouldn’t let go. He held on to it through the photograph, through his first night alone, until a nun finally pried it from his sleeping fingers. Sometimes the names we lose are less important than the ones we create.

John Francis Brennan, born Michael James O’Conor, died believing he was nobody’s child. But he was wrong. He was Margaret’s desperate hope. He was Agnes’ secret love. He was Joseph’s remembered sorrow. He was Mary and Thomas Brennan’s answered prayer. He was thousands of students first believer.

And in the end, isn’t that what we all are? Not the names on our birth certificates, but the marks we leave on other souls. John never found his mother, but he became what she had dreamed. Someone who taught others to read the world better than she could.

Someone who turned abandonment into abundance, silence into stories, orphanhood into opportunity. This is what the photograph doesn’t show, but what history proves. Love doesn’t always look like holding on. Sometimes it looks like letting go. Sometimes it looks like standing in the snow memorizing a window. Sometimes it looks like 73 letters never sent.

Sometimes it looks like teaching your own cousin to read without knowing she carries your mother’s eyes. The last entry in John’s memoir written two days before his death reads, “This paper shows only the name they gave me. But what matters are the names we leave in the hearts of others. I was nobody’s son, but I became everybody’s teacher. That’s enough. That’s more than enough. That’s everything.

” Before we close, a gentle reminder of the heart of this dramatized story inspired by real history. Sometimes love is the courage to let go so that another life can grow. Sometimes the name that matters is the one we write on other people’s hearts. May we remember that small acts, an extra lullabi, a wooden toy, a hand that won’t let go, can become the lifelines that carry someone through the years.

What part of this tale stayed with you? the thread in the baby’s fist, the letters never sent, or the classroom where a stutter turned into a voice. When have you seen a second chance change the course of a life? If you had to choose, what do you think matters more? The name we’re given or the names we earn by what we do for others.

If this dramatized narrative touched you, type the reflective word thread in the comments so I know you stayed to the end. Tell me what city you’re watching from. And if you’re comfortable, share a memory from your family’s past that might inspire future episodes.

If the story felt meaningful, please consider subscribing, liking, turning on the bell, and sharing or commenting to help this community grow. And if you want more true-to-life dramatizations with humane lessons at the end, click the end card and keep watching. There’s another story waiting for you. Thank you for honoring this piece of living memory with your time.