Dr. Emily Watson, a historian specializing in early 20th century American family structures, had attended dozens of estate auctions throughout New England. But something about the Blackwood collection felt different. The auctioneer explained that the items had been discovered in a sealed storage room of a Victorian mansion in Providence, Rhode Island, untouched for over a century.

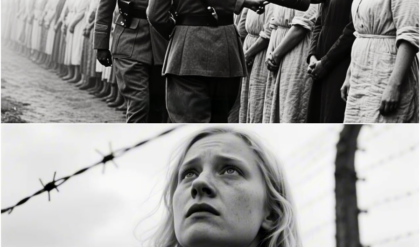

Lot 47, the auctioneer announced, holding up a large, ornately framed family portrait. Formal family photograph circa 1903 professional studio quality starting bid $50. Emily raised her paddle immediately, drawn by the photograph’s exceptional clarity and composition. The image showed a well-dressed family of seven arranged in the traditional formal pose of the era.

Parents seated in the center with five children of varying ages positioned around them. The father appeared distinguished in his dark suit, while the mother wore an elaborate dress with intricate bead work typical of the period’s formal wear. As the bidding continued, Emily studied the family’s faces through her small magnifying glass.

Four of the children displayed the serious composed expressions typical of formal portraits from 1903. Standing rigidly with hands folded, eyes fixed solemnly on the camera, the parents maintained the dignified bearing expected of prosperous Americans of their era. But something about the youngest child caught her attention and wouldn’t let go.

While the rest of the family maintained perfect formal composure, the little boy, perhaps four or 5 years old, displayed a wide, delighted grin that seemed utterly out of place in the solemn family portrait. His expression was so in congruous with the formal setting that it created an almost unsettling contrast with his family members serious demeanor.

Emily won the bidding at $180, considerably more than she had intended to spend, but her instincts told her this photograph contained a story worth investigating. As she carefully wrapped the portrait for transport, she noticed a small brass name plate at the bottom of the frame. The Blackwood family, Providence, Rhode Island, October 1903.

Back in her office at Brown University, Emily would discover that the little boy’s inappropriate grin was just the beginning of one of the most disturbing family mysteries in New England’s history. Under the bright lights of her research laboratory, Dr. Watson carefully examined every detail of the Blackwood family portrait.

Using highresolution digital scanning, she created detailed images that revealed aspects invisible to casual observation. What she discovered made the little boy’s grin even more disturbing. The formal studio setting appeared completely typical for 1903. An ornate Victorian chair, heavy drapery, and careful lighting that spoke of considerable expense.

The photographer had clearly been skilled and professional, suggesting this was an important family document rather than a casual snapshot. The family members were arranged in classic hierarchical order. James Blackwood, the patriarch, appeared to be in his mid-40s with the stern bearing of a successful businessman. His wife, Margaret, displayed the refined elegance expected of a prosperous merchant family’s matriarch.

Their four older children, three daughters, and a son, ranged in age from approximately 8 to 16, all maintaining the composed expressions appropriate for formal photography. But as Emily magnified the image of the youngest child, details emerged that made her increasingly uncomfortable. The boy’s grin wasn’t just inappropriately cheerful.

It was knowing, almost cunning. His eyes held an intelligence that seemed far beyond his apparent age. And there was something about his expression that suggested he was aware of something. The photographer and viewers weren’t supposed to see. More disturbing was what Emily noticed about the family’s positioning.

While the formal arrangement appeared conventional, closer examination revealed subtle tensions, the older children’s eyes showed traces of what looked like fear or anxiety, carefully controlled, but visible under magnification. Margaret Blackwood’s hands were clasped so tightly that her knuckles showed white through her gloves, and James Blackwood’s jaw appeared clenched despite his formally neutral expression.

Only the youngest child seemed completely relaxed and genuinely happy. a stark contrast that suggested he either didn’t understand whatever was making the rest of his family uncomfortable or he understood it all too well and found it amusing. Emily began researching the Blackwood family’s history, hoping to understand what circumstances might explain the strange dynamics captured in this seemingly normal family portrait.

The Providence Historical Society’s archives contained extensive records of the Blackwood family, who had been prominent in Rhode Island’s textile and shipping industries throughout the late 1800s. James Blackwood had built a substantial fortune through strategic investments in both manufacturing and import businesses, establishing his family as one of Providence’s most respected merchant dynasties.

But as Emily delved deeper into the family’s documentation, she began to find gaps and inconsistencies that suggested their public image might not have reflected their private reality. Birth records for the children showed normal progression for four of the five, but the youngest child’s documentation was peculiar.

Little Thomas Blackwood’s birth certificate listed his birth date as March 15th, 1898, which would make him 5 years old in the 1903 photograph. However, Emily found earlier family documents that referenced a different Thomas Blackwood, described as the family’s ward rather than biological son with references to his unusual circumstances and need for special care and attention.

More puzzling were references in James Blackwood’s business correspondence to the boy’s special requirements and payments made to what appeared to be medical specialists and private tutors. The amounts were substantial, suggesting that Thomas’s care involved considerable expense and specialized attention. Emily discovered a particularly intriguing letter from Margaret Blackwood to her sister, dated August 1903, just 2 months before the family portrait was taken.

Thomas continues to present challenges that require constant vigilance. James insists we maintain normal family appearances, but the boy’s nature makes this increasingly difficult. We have arranged for the family portrait as he requested, though I fear what people might notice if they look too carefully. The letter’s tone suggested that Thomas’s presence in the family involved some kind of ongoing difficulty or concern that the parents were working to conceal from public view.

But what kind of nature would require such careful management? and why would James Blackwood insist on including the boy in a formal family portrait if he posed such challenges? Emily realized she needed to research not just the family’s public records, but also medical and legal documents that might explain Thomas’s unusual status and the family’s apparent anxiety about his behavior.

Emily’s search through medical archives and hospital records revealed a pattern of consultations that painted a troubling picture of Thomas Blackwood’s early years. Beginning in 1899, when he would have been about one year old, the family had sought medical advice from specialists in Boston, New York, and even as far away as Philadelphia.

The medical records, while discreetly worded due to the era’s privacy customs, described a child who displayed developmental anomalies of behavioral and intellectual nature that puzzled the physicians who examined him. Dr. Marcus Whitmore of Boston Children’s Hospital had written in 1901. The child presents normal physical development but displays cognitive and emotional characteristics that appear inconsistent with typical childhood development patterns.

His intellectual capacity appears advanced beyond his chronological age. While his emotional responses to social situations are concerning, more specific details emerged from Dr. Sarah Chen’s notes from New York Presbyterian Hospital in 1902. Young Thomas demonstrates remarkable intellectual precostity, capable of complex reasoning and observation that would be exceptional in a child twice his age.

However, his empathetic responses appear significantly underdeveloped. He shows no distress when witnessing others pain and appears to find others discomfort amusing rather than concerning. The medical consultations had apparently focused on what modern psychology would recognize as signs of antisocial personality development.

But the primitive understanding of child psychology in 1903 had left the physicians unable to provide clear guidance to the family. Emily found correspondence between James Blackwood and Dr. Whitmore discussing management strategies for Thomas’s behavior. The doctor had recommended careful supervision to prevent the child from engaging in activities that might harm others and suggested that normal family interaction should be maintained to encourage appropriate social development.

Though vigilance is essential, the family portrait began to take on new significance as Emily understood it had been taken during a period when the Blackwoods were struggling to manage a child whose psychological development was causing serious concern. Thomas’s inappropriate grin now seemed less like childish exuberance and more like the expression of someone who understood far more about the family’s tensions than a normal 5-year-old should.

But Emily’s most disturbing discovery was yet to come, hidden in legal documents that revealed what had ultimately happened to young Thomas Blackwood. At the Rhode Island State Archives, Emily requested access to legal documents related to the Blackwood family estate. What she discovered there made Thomas’s unsettling grin in the family portrait even more chilling.

In January 1904, just 3 months after the family portrait was taken, James Blackwood had filed a petition with the Providence Family Court requesting that Thomas be declared a ward of the state due to dangerous behavioral tendencies that pose a risk to family safety. The petition included detailed documentation of incidents that had occurred throughout 1903.

The court records sealed for decades due to the sensitive nature involving a minor described a pattern of behavior that would have been deeply troubling to any family. Thomas had apparently been involved in a series of incidents involving the family’s pets, servants, and even his siblings that demonstrated what the court documents described as a concerning lack of normal emotional response and apparent enjoyment of others distress.

Margaret Blackwood’s testimony given in a closed court session described finding Thomas smiling with obvious pleasure while deliberately causing pain to the family cat and noted several occasions when servants had reported the boy attempting to harm them through deliberate mischief that could have caused serious injury. Most disturbing were the references to incidents involving Thomas’s siblings.

The court records indicated that the older children had been increasingly reluctant to be alone with Thomas and that several had reported to their parents that the e boy enjoys frightening them and has threatened to hurt them while smiling. Dr. Whitmore had provided expert testimony supporting the family’s petition, stating that the child displays characteristics consistent with what alienists term moral insanity, an inability to experience normal emotional connections with others combined with apparent satisfaction in causing distress.

Without intensive institutional intervention, such children often develop into adults who pose serious threats to society. The court had granted the Blackwood family’s petition and Thomas had been committed to the Rhode Island State Hospital for nervous and mental disorders in February 1904. The commitment papers indicated he was to remain there until such time as medical authorities determined he no longer poses a danger to himself or others.

Emily realized that the family portrait from October 1903 had been taken during the final months of Thomas’s time with the Blackwood family when they were already planning to have him institutionalized. His knowing grin suddenly seemed like the expression of a child who was aware of the chaos and fear he was creating in his family and who found it deeply amusing.

Emily’s research into the Rhode Island State Hospital’s historical records required special permissions due to the sensitive nature of mental health documentation, but her academic credentials and research purpose eventually gained her access to Thomas Blackwood’s institutional file. What she discovered there was a detailed chronicle of a child whose behavioral problems had continued and intensified after his commitment.

The hospital’s medical staff, led by Dr. Henry Morrison had documented Thomas’s progress through regular evaluations and incident reports that painted a picture of a profoundly disturbed child who seemed unable to develop normal emotional connections with others. Patient continues to display remarkable intellectual capacity while demonstrating complete absence of empathetic response. Dr.

Morrison had written in March 1904. Thomas shows no distress at being separated from his family and appears to view his circumstances as an interesting experiment rather than a punishment or treatment. The hospital staff had noted Thomas’s unusual ability to manipulate both other patients and staff members through what they described as superficial charm and apparent cooperation that masked his true intentions.

Several incident reports described Thomas deliberately provoking other patients to violence while maintaining his own appearance of innocence. But the most chilling aspect of Thomas’s institutional records was the staff’s growing recognition that traditional treatment methods were having no effect on his condition.

The child appears incapable of genuine remorse or emotional learning. One evaluation noted, “He can mimic appropriate responses when it serves his purposes, but shows no evidence of actual psychological development or improvement.” Emily found correspondence between Dr. Morrison and James Blackwood discussing the family’s continued financial responsibility for Thomas’s care.

The letters revealed that while the Blackwood family was meeting their financial obligations, they had requested that all communication about Thomas’s condition be conducted through their attorney rather than directly with family members. Mr. Blackwood has indicated that for the emotional well-being of his wife and remaining children, the family wishes to minimize direct contact with information about Thomas’s institutional progress. Dr.

Morrison had written to the family’s lawyer in 1905. While this is understandable given the traumatic circumstances of his commitment, it does suggest that Thomas’s reintegration with his biological family is increasingly unlikely. The institutional records continued through Thomas’s adolescence, documenting a pattern of manipulative behavior, lack of genuine emotional development, and what modern psychology would recognize as classic psychopathic personality traits.

Emily realized she was reading the documentation of one of the earliest cases of childhood psychopathy to be systematically recorded by American medical institutions. Emily’s investigation into the Blackwood family’s life after Thomas’s institutionalization revealed the profound impact his presence had on the entire family structure.

Through newspaper archives, social registers, and personal correspondence, she traced how the family had rebuilt their lives following the traumatic events of 1903 1904. The four older Blackwood children had all left Providence within a few years of Thomas’s commitment, despite the family’s substantial local business interests.

Maria, the eldest daughter, had married and moved to Boston in 1906. The two middle daughters had been sent to finishing schools in New York and had remained on the East Coast after graduation. Even James Jr., the oldest son, who would have been expected to inherit the family business, had relocated to California in 1908. Margaret Blackwood’s health had apparently suffered significantly following Thomas’s institutionalization.

Emily found references in local society pages to Margaret’s extended rest for her health and later mentions of her living as a semi-invalid who rarely appeared at social functions after 1905. James Blackwood had gradually liquidated his business interests in Providence, eventually relocating the family to a smaller estate in rural Connecticut where they could live more privately.

The move appeared to have been motivated by a desire to escape the social scrutiny and whispered rumors that had followed the family after Thomas’s dramatic removal from their household. But Emily’s most significant discovery was a cache of letters between Margaret Blackwood and her sister that had been preserved in a private family collection.

These letters written between 1904 and 1910 provided insight into the family’s emotional recovery from their ordeal with Thomas. We live now with the knowledge that evil can wear the face of innocence. Margaret had written in 1905. I look back at that family portrait and see how blind we were to what Thomas truly was.

His smile, which we took for childhood joy, was actually the expression of something dark and calculating that we failed to recognize until it was almost too late. Margaret’s letters described her ongoing nightmares about Thomas and her fears that his influence might have somehow affected her other children. I watch my remaining children constantly for signs of Thomas’s nature. Though Dr.

Whitmore assures me that such conditions are not contagious. Still, I cannot forget how he looked at his siblings, how he seemed to study their fears and find ways to exploit them. The correspondence revealed that the Blackwood family had lived in a state of constant anxiety during Thomas’s final years in their household, never knowing what disturbing behavior they might discover next.

Emily consulted with Dr. Robert Chen, a modern child psychologist at Brown University, to better understand Thomas Blackwood’s case from a contemporary clinical perspective. Dr. Dr. Chen’s analysis of the historical medical records provided insight into what the 1903 era physicians had been observing but lacked the theoretical framework to properly understand.

What you’re describing sounds like a textbook case of childhood onset conduct disorder with psychopathic traits. Dr. Chen explained, “The combination of intellectual precostity, absence of empathy, manipulation of others, and apparent enjoyment of causing distress are classic indicators of what we now recognize as antisocial personality disorder developing in early childhood.

” Doctor Chen noted that Thomas’s case was particularly striking because of how well documented it was during an era when child psychology was still in its infancy. The physicians treating Thomas were remarkably observant, even though they lacked the diagnostic categories we use today.

Their descriptions of his behavior are consistent with modern understanding of childhood psychopathy. The historical medical records had documented something that modern research had confirmed. Children who display these traits at such a young age rarely respond to treatment and typically develop into adults who pose serious risks to society.

The Blackwood family’s decision to institutionalize Thomas was probably the best choice available to them given the limited understanding and treatment options of their era, Dr. Chen observed. But Dr. Chen also pointed out something that made Thomas’ case even more unusual, the family’s recognition of the severity of his condition.

Many families in that era and even today struggle to accept that a young child could display such disturbing traits. The Blackwood’s willingness to take dramatic action suggests they had observed behavior that genuinely frightened them. Emily realized that the family portrait had captured a moment when the Blackwoods were still trying to maintain the appearance of normal family life while dealing with a child whose psychological development was fundamentally different from typical human emotional patterns.

Thomas’s grin represented not childhood innocence, but the expression of someone who understood he was causing fear and distress in his family and found it entertaining. That smile, Dr. Chen concluded after studying the magnified image, is probably the most authentic expression in the entire photograph.

While his family members are struggling to maintain composed appearances, Thomas is genuinely enjoying himself because he knows something they’re trying to hide from the photographer and the world. Emily’s research into Thomas Blackwood’s later life required extensive investigation through institutional archives, court records, and medical documentation.

What she discovered revealed the long-term outcome of one of New England’s earliest documented cases of childhood psychopathy. Thomas had remained at the Rhode Island State Hospital until 1914 when he turned 16. The institutional records from his teenage years showed continued behavioral problems, but also documented his growing sophistication at manipulating both staff and other patients.

Patient has developed considerable skill at presenting himself as reformed and cooperative, one evaluation noted. However, staff members report that his apparent progress is superficial and that incidents involving other patients continue when Thomas believes he is unobserved. At 16, Thomas had been transferred to a specialized facility for young adults in Massachusetts, where he spent another four years under institutional care.

But Emily discovered that in 1918, as America focused its attention and resources on World War I, many state institutions had been forced to release patients who were deemed manageable due to funding constraints and staff shortages. Thomas Blackwood had been among those released despite medical recommendations that he continue to receive institutional supervision.

The discharge papers noted that while patient continues to display antisocial tendencies, he has demonstrated ability to function in society without direct supervision and current institutional resources must be prioritized for more acute cases. Emily found scattered records suggesting that Thomas had spent his early adult years moving between different cities throughout New England, never staying in one place long enough to establish permanent ties.

Police records from various municipalities contained reports of incidents involving a Thomas Blackwood or individuals matching his description, but nothing that had led to serious criminal charges. The trail went cold in the mid 1920s, around the time Thomas would have been in his late 20s. Emily could find no death certificate, marriage record, or other official documentation that definitively tracked his later life.

But her most disturbing discovery was a series of unsolved cases from the 1920s and 1930s involving missing children and unexplained deaths in communities where Thomas had been documented as living temporarily. While no direct evidence connected him to these incidents, the pattern suggested that his release from institutional care might have had tragic consequences for others.

Emily realized she was documenting not just a family tragedy, but a case study in how society’s limited understanding of dangerous psychological conditions had potentially allowed a predator to operate freely for decades. Emily’s final research phase involved assembling all the documentation she had gathered to understand the complete story behind the Blackwood family portrait.

As she laid out the chronological evidence, the medical consultations, family correspondence, court records, and institutional documentation, the true significance of Thomas’s disturbing grin became clear. The photograph had been taken in October 1903 at a moment when the Blackwood family was desperately trying to maintain the appearance of normaly while secretly planning to have their youngest child institutionalized.

James Blackwood had insisted on the family portrait as part of his efforts to preserve their social standing and create a visual record of their family before Thomas’s removal would make such images impossible. But Thomas himself seemed to understand exactly what was happening.

His inappropriate grin wasn’t the expression of an innocent child unaware of his family’s distress. It was the knowing smile of someone who realized he had created chaos and fear in his household and found the situation amusing rather than troubling. The portrait captures a moment of profound family trauma disguised as conventional documentation, Emily wrote in her research conclusions.

While six family members struggle to maintain composed appearances for posterity, Thomas displays genuine beep pleasure because he understands he is the source of their carefully hidden distress. Emily arranged to present her findings to the American Historical Association’s annual conference, where her research was recognized as a significant contribution to understanding how families dealt with severe psychological disorders before modern diagnostic and treatment methods were available.

But she also worked with the Providence Historical Society to ensure that Thomas Blackwood’s story would serve as an educational case study for understanding childhood psychopathy and its impact on family structures. The family portrait, now properly contextualized, became part of an exhibit examining how photographic evidence can reveal hidden social realities when viewed with historical perspective and systematic research.

Margaret Blackwood’s final letter to her sister, written in 1910, provided the most poignant summary of their family’s ordeal. We learned that evil can indeed wear the face of childhood innocence, and that sometimes the most disturbing truth is hidden behind the most innocent smile. Thomas taught us that not all children are born with the capacity for love and empathy and that recognizing this reality, no matter how painful, is sometimes necessary to protect others from harm.

Emily’s research had revealed that the Blackwood family portrait of 1903 documented not just a formal family gathering, but a moment when parents had been forced to confront the reality that one of their children posed a genuine threat to their family’s safety and society’s well-being. Thomas’s unsettling grin had indeed hidden the truth, not the innocent joy of childhood, but the calculating pleasure of someone who understood exactly how much fear and pain he was capable of causing, and who found that knowledge deeply satisfying. Incap, the Blackwoods had unknowingly created a historical document that captured one of the most disturbing family secrets in New England’s history.

The smile of a child who had been born without the capacity for human empathy and who had learned to use that absence as a weapon against those who should have been able to love and trust.