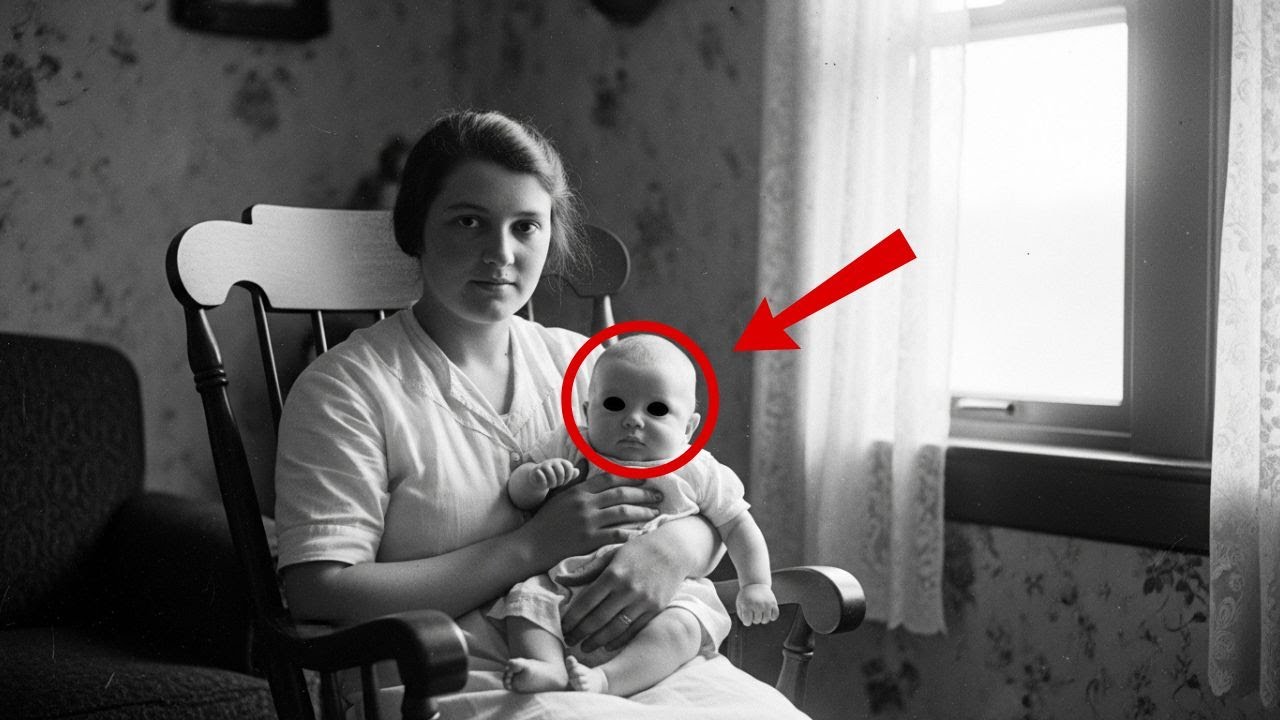

Rebecca Martinez, a forensic photography expert for the Los Angeles Police Department, had analyzed thousands of crime scene photographs and evidence images throughout her 15-year career. But nothing had prepared her for the photograph that elderly collector Thomas Wittmann brought to her private restoration studio on a foggy Tuesday morning in November 2024.

I acquired this at an estate sale in Pasadena last weekend, Thomas explained, carefully removing the photograph from a protective sleeve. The seller mentioned it was found in an old medical bag that belonged to a country doctor from the 1920s. Something about it has been bothering me ever since I got home. The photograph showed a tender domestic scene from 1924.

a young woman in her 20s, sitting in a wooden rocking chair, cradling a baby who appeared to be around 6 months old. She wore a simple white cotton dress typical of the era, her dark hair pinned back in a modest style. The setting appeared to be a modest parlor with floral wallpaper and lace curtains filtering soft daylight through a window. At first glance, it seemed like a perfectly ordinary portrait of motherhood from the early 20th century.

Rebecca positioned the photograph under her high-powered magnifying equipment, the same type used for analyzing forensic evidence. As she adjusted the lighting and focus, she immediately understood Thomas’s unease. While the mother’s face showed normal features and expression, when she zoomed in on the baby’s face, something was deeply wrong with the infant’s eyes.

“Have you noticed the baby’s eyes?” Rebecca asked quietly, her professional composure wavering slightly as she studied the image more closely. Thomas nodded grimly. That’s exactly what’s been haunting me. They’re completely black. Not just dark brown or photographed in shadow, but entirely black, like there are no pupils or irises at all.

In 40 years of collecting vintage photographs, I’ve never seen anything like it. Rebecca had worked with enough old photographs to know that various factors could cause unusual effects, lighting problems, chemical processing errors, or damage to the photographic plates. But this was different. The baby’s eyes appeared to be perfectly formed but completely void of any normal coloration, creating an unsettling contrast with the otherwise serene domestic scene. Mr.

Mr. Wittmann, do you have any information about who these people were or where this photograph was taken? Thomas Wittmann returned the next day with additional items from the estate sale that might provide clues about the mysterious photograph. He had purchased the entire contents of an old leather medical bag, hoping to find historical medical instruments for his collection, but instead discovered a treasure trove of documents that painted a disturbing picture. The bag belonged to Dr.

Harold Fleming, Thomas explained, spreading the documents across Rebecca’s workbench. He was a country doctor who practiced in rural Pennsylvania from 1920 to 1955. Most of these papers are routine medical records, but look at this. Among the yellowed papers was a patient file dated 1924, marked confidential unusual case. The file contained detailed notes about a baby born in the small town of Milfield, Pennsylvania, who exhibited what Dr. Fleming described as complete bilateral anoridia with associated complications. The medical terminology

was archaic, but Rebecca recognized some of the symptoms described. Anoridia, Rebecca murmured, reading through the careful handwriting. That’s a rare genetic condition where people are born without irises. the colored part of the eye. It would make the eyes appear completely black because you’d only see the large pupils.

The file contained multiple photographs of the same baby at different ages, all showing the same completely black eyes. But more disturbing were Dr. Fleming’s notes about the community’s reaction to the child. Parents report increasing hostility from neighbors. One entry read, “Local preacher claims child is marked by darkness.

family considering relocation due to superstitious fears of towns people. Thomas pointed to another document, a birth certificate for William James Morrison, born March 15th, 1924. Parents Mary Elizabeth Morrison and James Robert Morrison. The address listed was a rural route outside Milfield, Pennsylvania. There’s more, Thomas said, producing a letter dated December 1924. It was written by Dr.

for Fleming to a colleague at John’s Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. I am writing to document a case of severe anoridia in an infant patient that has unfortunately become the subject of local superstition and fear. The child is physically healthy aside from the ocular condition and associated photosensitivity, but the family faces increasing social persecution. I fear for their safety if they remain in this community much longer.

Rebecca studied the photograph again, understanding now why the baby’s appearance had seemed so unsettling. In 1924, without modern medical knowledge about genetic conditions, a baby born with completely black eyes would have seemed supernatural or even demonic to a superstitious rural community. We need to find out what happened to this family, Rebecca said. If Dr.

Fleming was right about the community’s hostility. This photograph might be documenting something much more serious than a medical oddity. Rebecca and Thomas decided to travel to Pennsylvania to investigate the Morrison family and the circumstances surrounding the disturbing photograph.

Milfield turned out to be a tiny rural community in the mountains of central Pennsylvania. Population barely 800 people. the kind of place where everyone knew everyone else’s business and family histories stretched back generations. Their first stop was the local historical society housed in a converted general store on Main Street. The volunteer coordinator, Mrs.

Dorothy Hansen, was a lifelong resident in her 70s, who immediately recognized the Morrison name when they mentioned it. “Oh my, I haven’t heard that name spoken aloud in probably 30 years.” “Mrs. Hansen said, her expression growing troubled. My grandmother used to tell stories about the Morrison family, but they weren’t pleasant stories.

There was some kind of tragedy back in the 1920s that my family didn’t like to talk about. She led them to a backroom filled with local newspapers, church records, and family genealogies dating back to the town’s founding in 1887. Let me see what I can find about 1924, she said, pulling out bound volumes of the Milfield County Herald, the local weekly newspaper that had covered community events for decades. After an hour of searching, Mrs.

Hansen found what they were looking for. The October 15th, 1924 edition contained a small article buried on page three. Morrison family departs local community. The James Morrison family has sold their property on rural Route 7 and departed for parts unknown. Community members expressed relief at the resolution of recent tensions.

Recent tensions? Rebecca asked. What kind of tensions? Mrs. Hansen found earlier issues that provided more context. Throughout the summer and fall of 1924, there had been several mentions of community concerns and unusual circumstances surrounding the Morrison family.

Though the articles were vague and seemed to be deliberately avoiding specifics, but in Number the church records from the Milfield Baptist Church, they found more detailed information. Reverend Samuel Phillips had kept meticulous records of his congregation, including notes about pastoral concerns and community issues. His entry for July 1924 was chilling. Congregation continues to express fears about the Morrison infant. Several members have requested that the family be asked to leave the community.

I have counseledled patients and Christian charity, but fear that emotions are running too high for reason to prevail. An entry from September 1924 was even more ominous. Incident occurred at Morrison residence last evening. Windows broken, threatening messages left. Dr. Fleming reports family is in hiding and fears for their safety.

I have failed to convince my congregation that this child is not a supernatural threat. May God forgive us all for what we have allowed fear to become.” Thomas and Rebecca looked at each other across the dusty church records. The photograph they had been examining wasn’t just a medical curiosity.

It was evidence of a family that had been driven from their home by superstition and fear. All because their baby had been born with a rare genetic condition that made his eyes appear completely black. Their next stop was the Milfield County Courthouse where they hoped to find more official records about the Morrison family and the circumstances of their departure.

The elderly clerk, Robert Phillips, grandson of the Baptist preacher who had tried to protect the Morrison family, had grown up hearing whispered stories about the events of 1924. “My grandfather kept a private diary separate from his church.” “Records,” Robert explained as he led them through the courthouse archives. “After he died in 1967, my father found it in his desk.

Most of it was routine pastoral observations, but the entries about the Morrison family were so disturbing that our family kept the diary locked away for decades. He produced a small leatherbound book and opened it to the entries from late 1924.

Reverend Phillips had written in detail about his attempts to educate his congregation about the baby’s medical condition, his frustration with their superstitious fears, and his growing concern for the Morrison family’s safety. [Music] August 12th, 1924, Dr. Fleming visited again today to explain the child’s condition to anyone who would listen. He showed medical textbooks and photographs of other children born with similar conditions, but fear has taken root too deeply. Mrs.

Henderson claims the baby’s eyes follow her when she walks past the Morrison house. Mr. Thompson insists the child’s presence is causing his crops to fail. I fear we are witnessing the same ignorance that led to witch trials in centuries past. September 20th, 1924. The situation has deteriorated beyond my ability to control.

Someone threw rocks at the Morrison house last night, shattering two windows. Mary Morrison came to me in tears, begging for help. The baby is healthy and normal in every way except for his unusual eyes. Yet half the town treats him as if he were a demon. I have arranged for Dr. Fleming to document everything, hoping that someday this injustice will be remembered and learned from.

But the most revealing entry came from October 1924. Dr. Fleming showed me photographs he has been taking of the Morrison baby, hoping to create a medical record that might help other families facing similar circumstances. He fears this may be his last opportunity, as the family has decided they must leave town for their safety. The final photograph he took shows Mary Morrison holding her son.

And despite everything they have endured, her face shows nothing but love and protectiveness. History will judge us harshly for what we have driven this family to endure. Rebecca realized they were looking at the exact photograph Thomas had purchased at the estate sale. Dr.

Fleming’s final documentation of a family being destroyed by ignorance and fear. The baby’s completely black eyes, which had seemed so disturbing at first glance, were simply a rare genetic condition that a 1924 rural community had been unable to understand or accept. “Mr. Phillips?” Rebecca asked. “Do you have any records of where the Morrison family went after they left Milfield?” Robert shook his head sadly.

My grandfather’s last entry about them just says they disappeared into the night like refugees from their own neighbors. No forwarding address, no contact information. It was as if they had never existed. Rebecca and Thomas spent two more days in Milfield visiting the site where the Morrison house had once stood and interviewing elderly residents who might remember family stories about the events of 1924.

What they discovered painted an increasingly tragic picture of a community that had allowed fear and superstition to destroy an innocent family. The Morrison property on rural Route 7 was now an empty field with only the remnants of a stone foundation visible among the weeds.

A neighbor, 89-year-old Earl Thompson, was the grandson of the man who had claimed the baby’s presence was causing his crops to fail. Earl had grown up hearing the story and felt compelled to share what he knew. “My grandfather was ashamed of what happened here for the rest of his life,” Earl explained as they stood where the Morrison house had once been.

He used to tell me that the baby was just a normal child with something different about his eyes. But people back then didn’t understand medical conditions like we do now. They saw something they couldn’t explain and decided it must be evil. Earl led them to the old Milfield cemetery where they found something unexpected. A small unmarked grave dated 1924.

Local legend says this is where they buried something belonging to the Morrison family before they left town, Earl said quietly. My grandfather always suspected it might be medical records or photographs that Dr. Fleming couldn’t take with him. With the cemetery caretaker’s permission, they examined the area around the unmarked grave and discovered a metal box buried just beneath the surface.

Inside, wrapped in oiled cloth, were additional medical records and photographs documenting baby William Morrison’s condition. Dr. Fleming had apparently hidden this evidence before the family’s departure, perhaps hoping that someday it would be found and the true story would be told. The photographs showed William Morrison at different stages of his first year of life, and they revealed something that the single photograph Thomas had purchased couldn’t show. Despite his unusual appearance, the baby was clearly

healthy, alert, and responsive. In several pictures, he was smiling and reaching for toys displaying all the normal behaviors of a developing infant. But the most significant item in the buried box was a letter Dr. Fleming had written but never sent. Addressed to whoever may find these records. In it, he explained his decision to hide the documentation.

I have failed to protect this family from the ignorance of their community, but I will not let their story be forgotten. William Morrison was born with bilateral anoridia, a rare but harmless genetic condition that causes the absence of irises in the eyes. He was a normal, healthy child whose only crime was looking different from other babies. If these records are ever found, I pray they will serve as a reminder that fear of the unknown can make good people do terrible things.

The letter continued, “I have helped the Morrison family relocate to a larger city where William can receive proper medical care and hopefully grow up without the burden of superstition, but I fear the trauma of their experience here will haunt them forever.

May God forgive us all for failing to protect an innocent child in his loving family.” Rebecca carefully photographed all the documents before rearing them, knowing they now had enough evidence to piece together the complete story of what had happened to the Morrison family in 1924. Back in Los Angeles, Rebecca used her forensic research skills and law enforcement contacts to try to trace what had happened to the Morrison family after they left Milfield.

The trail was nearly a century old, but she was determined to find out if William Morrison had survived his traumatic infancy and what kind of life he had managed to build despite his unusual condition. Her first breakthrough came through hospital records in Philadelphia where she found documentation of a baby named William Morrison being treated for anoridia and associated vision problems in late 1924.

The medical records showed that Dr. Elena Rodriguez, an opthalmologist at Pennsylvania Hospital, had provided specialized care for the infant and had written detailed notes about his condition. Patient presence with complete bilateral anoridia. Dr. Rodriguez had written despite dramatic appearance of eyes child is otherwise healthy and developing normally.

Parents report significant social persecution due to child’s appearance. have recommended relocation to urban environment where medical resources and social tolerance may be greater. Through the hospital’s patient files, Rebecca was able to trace the Morrison family to a boarding house in South Philadelphia where they had lived under the name Morris, apparently shortening their surname to avoid being tracked by anyone from their former community.

City directory records showed James Morris working as a factory laborer while Mary Morris took in sewing to supplement their income. The trail continued through school records where Rebecca found evidence that William Morris had attended public school in Philadelphia despite his vision problems.

His school files contained notes from teachers describing him as a bright and capable student who requires some accommodation for light sensitivity, but shows no other limitations due to his ocular condition. But the most significant discovery came through social security records, which showed that William Morris had legally changed his name to William Marshall when he turned 18 in 1942.

The name change petition filed in Philadelphia County Court included a statement explaining his decision. I wish to distance myself from the circumstances of my early childhood and create a new identity free from the prejudice and fear that have followed my family for 18 years.

Rebecca’s law enforcement contacts helped her trace William Marshall through military records where she discovered that despite his vision problems, he had found a way to serve in World War II in a non-combat role working as a communications u specialist in the Army Signal Corps. His military file contained a photograph from 1943 that showed a young man whose completely black eyes were still striking, but who carried himself with confidence and dignity.

After the war, the records showed William Marshall had used the GI Bill to attend college, eventually earning a degree in social work. He had dedicated his career to helping children with disabilities and had worked for the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services for 35 years before retiring in 1989. “Thomas,” Rebecca said excitedly when she called to share her discoveries.

William Morrison survived. He not only survived, he thrived. and he spent his life helping other children who faced challenges similar to what he had experienced. Rebecca’s investigation took a dramatic turn when she discovered that William Marshall had married in 1951 and had three children, all of whom had been born with normal eyes.

Through genealogy websites and public records, she was able to identify his surviving family members, including a daughter named Susan Marshall Chen, who lived in Sacramento, California. When Rebecca called Susan to explain her research, the response was immediate and emotional. “You found the photograph?” Susan said, her voice breaking. “My father told us it existed, but we never thought we’d see it.

He used to say it was the last picture of him with his mother before their world fell apart.” Susan agreed to meet with Rebecca and Thomas in Sacramento the following weekend, bringing with her a collection of family documents and photographs that filled in the missing pieces of William Marshall’s remarkable life story.

As they sat in Susan’s living room, surrounded by pictures of her father at different stages of his life, she shared the stories he had told her about his traumatic childhood in Pennsylvania. Dad always said that 1924 was the year his family became refugees in their own country. Susan explained he remembered being carried away from their house in the middle of the night with his mother crying and his father angry at having to abandon everything they owned. They never spoke about what happened in Pennsylvania. It was too painful.

But William Marshall had also told his children about the few people who had tried to help his family, particularly Dr. Fleming and Reverend Phillips. Dad always said that Dr. Fleming was the only person who saw him as a child instead of a medical curiosity or a supernatural threat. He kept that doctor’s kindness in his heart for his entire life.

Susan showed them a letter her father had written to his grandchildren shortly before his death in 2003 explaining his condition and his experiences growing up with anoridia. In it, he had written, “I learned early in life that people fear what they don’t understand. But I also learned that there are always some people who choose compassion over fear. I tried to be one of those people in my own life and career.

” The letter continued, “I spent 35 years working with disabled children and their families, and I often thought about that baby in the 1924 photograph, the child whose appearance frightened an entire community. That baby grew up to help hundreds of other children who were different in some way. Sometimes our greatest challenges become our greatest strengths.

” Susan also shared that her father had never forgotten his original family name or his hometown in Pennsylvania. Every year on his birthday, he would light a candle for his mother, Mary, who had protected him with such fierce love during those terrible months when their neighbors turned against them.

He said she never once made him feel like there was anything wrong with him, even when everyone else was treating him like a monster. The photograph you found, Susan continued, shows the last moment of his mother’s happiness before their world collapsed. Dad always said you could see in her face that she knew something terrible was coming, but she was determined to hold on to her love for her child no matter what.

Word of Rebecca’s research began to spread through genealogy forums and social media where it attracted the attention of medical historians and researchers studying historical cases of genetic conditions. Dr. Michael Harrison, a specialist in anoridia at the National Eye Institute, contacted Rebecca after reading about the 1924 photographs and medical records. “This case is medically significant,” Dr.

Harrison explained during a video conference call with Rebecca, Thomas, and Susan. Anoridia affects only about 1 in 50,000 to 100,000 births, and complete bilateral anoridia like Williams is even rarer. The photographs Dr. Fleming took in 1924 represent some of the earliest documented cases of this condition in American medical literature. But Dr. Harrison was more interested in the social aspects of the case than the medical ones.

What happened to the Morrison family illustrates a pattern that was unfortunately common in the early 20th century. Children born with unusual physical conditions were often subjected to superstition and persecution, especially in isolated rural communities where medical knowledge was limited.

He had researched other historical cases and found similar stories of families being driven from their communities because of children born with conditions that made them appear different or frightening. The Morrison case is particularly well documented because of Dr. Fleming’s efforts to preserve the evidence.

Most similar cases left no historical record because the families simply disappeared and tried to forget their trauma. Susan had been working with Dr. Harrison to donate her father’s medical records and photographs to the National Institutes of Health, where they would be preserved as part of a historical collection documenting the experiences of people with rare genetic conditions.

Dad would have loved knowing that his story might help other families avoid what he went through, she said. Meanwhile, Thomas had been in contact with the Milfield Historical Society, sharing copies of the documents they had discovered and encouraging the community to acknowledge what had happened to the Morrison family in 1924. Mrs.

Dorothy Hansen had been working with the town council to create a memorial acknowledging the injustice that had been done to the Morrison family. We can’t change what our ancestors did, Mrs. Hansen had told the local newspaper. But we can make sure it’s remembered and learned from.

Fear and ignorance drove a innocent family from their home, and we need to own that history. The story had also attracted the attention of disability rights advocates who saw William Marshall’s journey from persecuted child to successful advocate as an inspiring example of resilience and transformation. Susan had been invited to speak at conferences about her father’s life and the importance of accepting and supporting children with visible differences.

The baby in that 1924 photograph grew up to help hundreds of other children who faced challenges because they looked different, Susan told audiences. His completely black eyes, which had seemed so frightening to people in 1924, became a source of strength and empathy that guided his entire career. 6 months after Rebecca’s initial discovery, representatives from the Milfield community made an unprecedented gesture, Mayor Patricia Coleman and Reverend David Phillips, the great grandson of the pastor who had tried to protect the Morrison family, traveled to Sacramento to meet with Susan Marshall Chen and formally apologized for what their community had done to her father’s

family in 1924. The meeting took place in Susan’s living room with Rebecca and Thomas present as witnesses to the historic reconciliation. Mayor Coleman carried with her a formal resolution passed by the Milfield Town Council, acknowledging the injustice done to the Morrison family and establishing a scholarship fund for children with disabilities in William Marshall’s memory.

We cannot undo the fear and ignorance that drove your father’s family from their home,” Mayor Coleman said, presenting the resolution to Susan. “But we can acknowledge that what happened was wrong, and we can commit to ensuring that such intolerance never happens again in our community.

” Reverend Phillips, representing the church where his greatgrandfather had tried to preach acceptance and compassion, offered his own apology. My great-grandfather’s diary records his shame at failing to protect your family from his own congregation’s fears. He carried that regret for the rest of his life. And our church has carried it as well. We want to honor your father’s memory by committing ourselves to the kind of radical acceptance and love that should have been shown to your family in 1924.

Susan accepted the apologies graciously, but also used the opportunity to challenge both the Milfield representatives and everyone following the story to think more deeply about how they responded to difference and disability in their own communities. My father used to say that every generation has to choose between fear and compassion.

Susan told them, “The people of Milfield in 1924 chose fear, but that doesn’t mean we have to keep making that choice. Every time we see someone who looks different, acts different, or needs different accommodations, we have the opportunity to choose compassion instead. The scholarship fund established in William Marshall’s memory would provide financial assistance for children with disabilities to attend college with preference given to students who had overcome social persecution or discrimination because of their conditions. The first scholarship would be awarded in 2025, exactly 100

years after William Morrison had left Milfield as a refugee from his own community. Rebecca had been working with a documentary filmmaker to create a short film about the discovery of the 1924 photograph and the story it revealed. The film titled The Eyes of Compassion: William Marshall’s Journey would premiere at the Milfield Historical Society and be distributed to schools and medical facilities as an educational resource about accepting disability indifference. Sometimes, Rebecca reflected as she looked at the

original 1924 photograph. The most disturbing images tell the most important stories. That baby’s black eyes, which seemed so frightening a century ago, led us to a story about the power of love to overcome fear and the importance of protecting those who are vulnerable because they’re different.

A year after Thomas Wittmann first brought the mysterious 1924 photograph to Rebecca’s studio, the image had become a powerful symbol of both historical injustice and contemporary hope. The photograph now resided in the Smithsonian’s collection of American medical history where it served as a centerpiece for an exhibition about the social treatment of genetic conditions throughout the 20th century. Dr.

Elena Martinez, the current director of the National Institute for Rare Genetic Disorders, had used William Marshall’s story as the foundation for a nationwide initiative to educate communities about accepting children born with visible differences. The William Marshall Project provided resources for families, schools, and medical professionals dealing with rare conditions that made children appear unusual or frightening to those unfamiliar with such conditions.

The 1924 photograph shows us a moment when love and fear existed side by side, Dr. Martinez explained at the Smithsonian exhibition opening. Mary Morrison’s face shows pure maternal love as she holds her son. But we know that outside the frame of that photograph, their community was preparing to destroy them. Today, we have the medical knowledge and social awareness to make different choices.

Susan Marshall Chen had become a prominent advocate for disability acceptance, traveling across the country to share her father’s story and challenge audiences to examine their own responses to difference. She always carried with her a copy of the 1924 photograph alongside pictures of her father throughout his life as a young soldier in World War II, as a social worker helping disabled children, as a grandfather reading to his grandchildren.

This photograph captures the moment before my father’s world fell apart, she would tell audiences. But it also captures the love that sustained him through everything that followed. His mother’s arms around him in this picture gave him the strength to survive persecution, to build a successful life, and to spend that life helping other children who faced similar challenges.

Back in Milfield, the town had undergone its own transformation. The site where the Morrison House had once stood was now a small memorial park with a plaque telling the story of the family that had been driven away by fear in 1924. The annual Mum William Marshall memorial lecture brought speakers to the community to discuss disability rights, historical justice, and the ongoing challenge of choosing compassion over fear.

Rebecca Martinez had returned to her forensic photography work, but with a deeper appreciation for the stories that old images could tell, she had established a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping families research historical photographs and documents that might reveal forgotten stories of injustice or resilience.

Every old photograph is a door into the past, Rebecca reflected as she looked one final time at the image that had started it all. Sometimes those doors open onto dark chapters of history that we’d rather forget. But they also open onto stories of love, courage, and survival that inspire us to be better than those who came before us.

The baby with the completely black eyes who had seemed so disturbing when Thomas first noticed him in that 1924 photograph had become a symbol of hope and transformation. His story proved that the most challenging beginnings could lead to the most meaningful lives and that love could indeed triumph over fear, but only when people chose to let it. As visitors to the Smithsonian exhibition looked at Mary Morrison holding her infant son, they saw not a frightening medical curiosity, but a mother’s fierce love protecting her child against a world that didn’t understand him. And in that love, they found the courage to examine their own hearts and choose compassion

over fear in their own encounters with difference and disability. The completely black eyes that had once terrified an entire community had become windows into the deepest truths about human nature. That our greatest fears often stem from our own ignorance.

And that our greatest strength comes from our ability to love those who need our protection most.