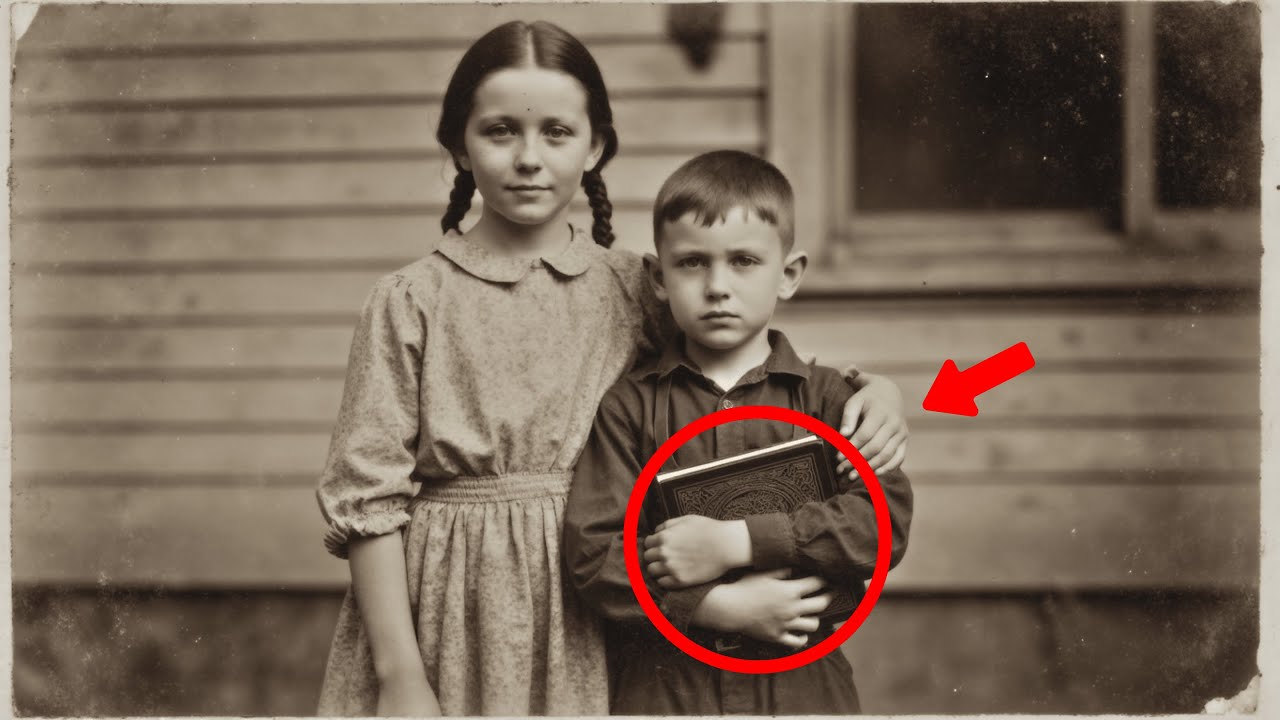

What would you do if your own family told you that education was not meant for you? In 1913 in rural Alabama, two children stood together in front of a wooden schoolhouse wall. One of them was allowed to cross the threshold and learn. The other was condemned to stay outside.

Decades later, a hidden notebook and a single photograph would reveal the cost of that silence and the strength of a girl who refused to give up her name.

In 1913, a photographer captured something that would haunt an entire family for generations. Two children stood before a weathered schoolhouse wall in rural Alabama, but only one of them had the right to walk through its doors. The girl in the photograph, Sarah Thompson, would spend the next 50 years fighting for something most take for granted, the ability to read her own name.

And if you stay until the end, you’ll discover why she smiled in that photo. despite knowing her brother James would be dead within 2 years and how a secret notebook hidden in a barn would change everything five decades later. This photograph was discovered in 1987 tucked inside a family Bible in Birmingham, Alabama. The edges were worn from decades of handling as if someone had traced the faces with their fingers countless times.

When historians from the Alabama Department of Archives first examined it, they noticed something peculiar about the girl’s hands, they were already scarred, marked by lie burns from washing clothes in the creek behind their cabin.

Sarah Thompson was 11 years old, and those scars tell us she’d been working since she was six. But look closer at her eyes in that photograph. There’s a defiance there that the camera almost missed. The photographer, whose name appears in Rosenwald Fund Records as Samuel Morrison, wrote in his journal that day about a girl who stood at the school door for 20 minutes before he asked her to join the picture.

She knew she wasn’t allowed inside. In 1910, Alabama, census records show that only 77.7% of white rural girls could read, and in the poorest counties, that number dropped to less than half. Sarah Thompson would become one of those statistics, but not by choice. Her brother James, 9 years old and clutching his new notebook like a prize, had no idea that his sister watched him walk to school every morning with a mixture of love and bitter envy. Their father, William Thompson, wasn’t a cruel man.

Farm records from Madison County show he owned 8 acres of cotton land that barely produced enough to feed his family. When the county assessor visited in 1912, he noted that the Thompsons owned one mule, six chickens, and debts totaling more than their annual income. Education for a daughter was a luxury they couldn’t afford.

Not when her hands were needed for washing, mending, and tending to the younger children who would come. But Sarah had already begun her rebellion. The night before this photograph was taken, she had snuck into James’ school bag and traced her fingers over the letters in his primer. She couldn’t read them, but she memorized their shapes. The capital S that started her name looked like a snake. The A was a tent.

The R resembled a person walking with a cane. She was creating her own alphabet, one symbol at a time, and James had begun to notice. What nobody knew that spring day in 1913 was that the photographer, Samuel Morrison, wasn’t just documenting rural life. Records discovered in the Louiswis Hine collection reveal he was part of a network of progressive educators documenting educational inequality across the South.

He left something behind that day, hidden beneath the schoolhouse steps where Sarah would find it a week later. A small primer wrapped in oil cloth. Inside the cover, he had written words that Sarah wouldn’t be able to read for another 50 years. For the girl who dreams of reading, your day will come. James had started to notice his sister’s late night struggles with his school books.

At first, he was annoyed when he found her asleep at the kitchen table. His primer opened to a page about farm animals. But something shifted in him when he saw her finger resting on the word horse and realized she had been tracing it over and over until exhaustion took her. The next morning, he did something that would define both their lives.

He picked up a stick and drew five letters in the dirt. S A R A H. Their mother, Elizabeth Thompson, watched from the cabin window as her son taught her daughter to write her name in the red Alabama dirt. Church records from the Madison Baptist congregation note that Elizabeth Thompson could barely sign her own name on her wedding certificate in 1901.

She had married at 14, bore her first child at 15, and by 30, her hands were as gnarled as an old woman’s from years of lie and labor. When she saw her children in the dirt that morning, she didn’t call Sarah back to help with the washing. She let her daughter have that moment, knowing it might be one of the few she’d get. 3 weeks after the photograph was taken, the spring rains came early and hard.

The Thompson family’s cotton crop began showing signs of blight, a disaster that would push them even deeper into poverty. Sarah’s secret lessons with James would have to become even more secret because now every moment not spent working threatened their survival. But something had been awakened in both children that day in front of the schoolhouse.

James had discovered he had the power to give his sister something precious. And Sarah had tasted something she would hunger for the rest of her life. knowledge. The county school superintendence report from June 1913 noted that enrollment for boys had increased by 12% that year, while enrollment for girls had dropped by 8%.

The report attributed this to economic necessities requiring female children to assist with household duties. What the report didn’t capture was the tragedy playing out in thousands of homes across rural Alabama, where girls like Sarah press their faces against windows, watching their brothers walk toward futures they could never have.

But Sarah Thompson was about to prove that sometimes hunger for knowledge is stronger than any law or tradition. She just didn’t know yet that the price would be everything she loved. 6 months before that photograph was taken, Sarah Thompson made a discovery that changed everything.

Hidden in the root cellar beneath their cabin, wrapped in burlap and covered with preserving jars, she found her mother’s secret, a McGuffy reader from 1889, its pages yellow and brittle with Elizabeth May Johnson, age 10, written inside the cover in fading ink. Her mother had once been a girl who could read.

The Moonlight Schools movement records from Kora Wilson Stewart’s archives confirm that thousands of women across the South hid their literacy from their husbands, believing that seeming too educated would bring shame to their families. Sarah confronted her mother that night while kneading bread for the next day’s breakfast.

Elizabeth’s hands stopped moving in the dough, and for a moment, Sarah saw something in her mother’s eyes she’d never seen before. Fear mixed with longing. Then Elizabeth spoke words that would echo in Sarah’s mind forever. Reading is a dangerous gift for a poor woman, Sarah. It makes you want things you can never have. It makes you see how small your world is.

And there’s no pain worse than knowing you’re trapped. But even as she said it, Elizabeth pulled the reader from its hiding place and opened it to the first page. That winter of 1912 became their secret season. While Father and James slept, mother and daughter would sit by the dying embers of the cook stove, and Elizabeth would trace her finger under words she barely remembered how to pronounce.

The Alabama temperature records show it was one of the coldest winters on record, with temperatures dropping below freezing for 43 nights straight. But Sarah later told her granddaughter that she never felt the cold during those midnight lessons, warmed by the fire of finally understanding that letters made sounds, sounds made words, and words made meaning. James began to notice his sister’s exhaustion during their dawn chores.

One morning, milking their skinny cow in the frozen barn, he asked her directly why she looked so tired. Sarah wanted to lie, but something in her brother’s eyes made her tell the truth. She expected anger or mockery. Instead, 9-year-old James made a decision that would define his short life. He began deliberately learning extra lessons at school, not for himself, but to bring home to Sarah.

The teacher, Miss Margaret Foster, noted in her grade book that James Thompson suddenly became her most eager student, always asking for extra reading assignments. The system they developed was ingenious in its simplicity. James would memorize entire pages from his primers and readers, then recite them to Sarah while they did their chores.

To anyone watching, they were just a brother and sister talking while feeding chickens or gathering eggs. But James was giving Sarah something precious. The rhythm and pattern of written English. He taught her that sentences had beginnings and endings, that questions sounded different from statements, that stories had shapes.

The 1915 Epidemic Records would later note that James Thompson, age 11, died knowing more about language than most adults in Madison County. Their father, William, wasn’t an educated man, but he wasn’t stupid. County records show he could sign his name and do basic arithmetic skills that made him more literate than many of his neighbors.

One February evening, he caught Sarah with one of James’s books. The scene that followed was documented years later in a letter Sarah wrote to her daughter. Papa didn’t hit me. That would have been easier. Instead, he sat down heavy in his chair and said, “Every minute you spend with those books is a minute stolen from this family’s survival. You want your brother to starve so you can play at being something you’re not.

” The guilt was more effective than any beating could have been. But the secret lessons continued, now with a desperate edge. Sarah developed her own code with James, using riverstones to represent letters. While washing clothes at the creek, she would arrange them in words, and James would correct her mistakes by casually kicking stones out of place or adding new ones. Their mother watched from the cabin, never saying a word.

But sometimes Sarah would find a piece of charcoal left by the washing bucket, perfect for practicing letters on flat rocks when no one was looking. The spring of 1913 brought two visitors who would change the family’s fate. The first was the photographer, Samuel Morrison, whose real purpose Sarah wouldn’t understand for decades. The second was Mrs.

Abigail Foster, a wealthy plantation owner’s widow who needed washing done for her household. She noticed Sarah’s intelligence immediately when the girl correctly calculated the payment for multiple loads without using her fingers to count. Mrs. Foster began bringing newspapers with her laundry, claiming they were for wrapping, but always leaving them behind.

Sarah couldn’t read them yet, but she studied them like maps to a treasure she couldn’t quite reach. By April 1913, just weeks after the photograph was taken, Sarah could recognize nearly a hundred words by sight. James had taught her a trick. Every word was a picture if you looked at it right. House looked like it had a roof in the middle. Mother had two humps like their mother’s shoulders when she was tired. Love was short and round, like a hug.

Their system was imperfect and slow, but it was working. The tragedy was that time was running out faster than either of them knew. The night before everything changed, James gave Sarah a gift that she would keep for 60 years.

Using a piece of paper torn from his composition book, he had written out the entire alphabet in his careful, childish hand. Below each letter, he had drawn a picture. A for apple, B for barn, C for cow. But when Sarah looked closer, she realized each picture was specific to their life. The apple had a worm in it, like the ones from their single apple tree. The barn had a broken door like theirs.

The cow was skinny with ribs showing. He had created an alphabet that belonged only to them, a secret language of poverty and love. At the bottom of the page, in letters so small she could barely see them, he had written, “For Sarah from James Forever.” December 1914 arrived with a catastrophe that would test everything Sarah had learned about survival.

Their mother, Elizabeth, collapsed while hanging laundry in the freezing wind. The doctor from town, whose visit cost them their last chicken and a promise of future payment, diagnosed pneumonia. Medical records from Madison County show that pneumonia killed more women than any other disease that year, particularly those weakened by years of hard labor and poor nutrition.

Elizabeth Thompson had 2 weeks to live, though no one would tell Sarah that truth. The medicine that might save her mother cost $3, more money than the Thompson family had seen in months. Sarah made a decision that would haunt her forever. She took the primer the photographer had hidden for her, the one she had been using to practice reading every night, and walked 8 miles to town in worn shoes that let in the December cold.

The pawn shop owner, Mr. Gerald Watson, whose ledger was later donated to the County Historical Society, recorded the transaction. One reading primer, good condition, purchased for 30 cents from Thompson Girl, December 15th, 1914. It wasn’t enough for the medicine, but it was enough for ingredients to make a pine needle tea that old Mrs.

Jefferson, a former slave who knew healing ways, promised might help. Sarah’s ability to read the medicine bottle labels at the general store saved her mother from a different fate. The store clerk, either through ignorance or malice, had tried to sell her ldinum instead of the cough mixture she needed.

But Sarah recognized the word opium on the bottle, one of the words James had taught her because their neighbor had died from too much of it. She pointed to the right bottle, and the clerk, surprised that this raggedy girl could read, gave it to her for the correct price. Elizabeth Thompson would survive her pneumonia, though her lungs would never fully recover.

James watched his sister transform during their mother’s illness. At 10 years old, he was old enough to understand that Sarah had become the true head of their household. Making decisions their father was too broken by poverty to make. School attendance records show that James missed 17 days during December 1914 and January 1915, staying home to help Sarah manage the household while their mother recovered. During those long days, their lessons reversed.

Now Sarah was teaching James the survival skills she had mastered. how to make soup from almost nothing, how to keep the fire going with damp wood, how to negotiate with creditors who came to their door. But the secret lessons continued, now with a desperate urgency. Sarah had tasted enough knowledge to know how much she didn’t know.

She began to see words everywhere, on the coffee sacks at the general store, on the patent medicine bottles, on the hymn books at church. She realized that the whole world was speaking a language she could only partially understand. And the frustration burned in her chest like fever. James, seeing his sister’s hunger, made a dangerous decision. He stole a book from school.

The book was Beautiful Joe, the story of an abused dog who finds a loving home. The county library records indicate it was donated to the school by the Lady’s Christian Temperance Union in 1910. James hid it in the barn wrapped in feed sacks. And every evening after chores, he and Sarah would retreat there. By the light of a candle stub, he would read aloud while Sarah followed along, her finger under each word, connecting sounds to symbols.

The barn was freezing, and more than once they had to stop because their fingers were too numb to turn pages. But Sarah later said those hours in the barn were when she truly learned to read. Not just recognize words, but understand stories. Their father discovered them on a February evening in 1915. William Thompson stood in the barn doorway, his face unreadable in the lamplight.

Sarah waited for the explosion, for him to beat James for stealing, to forbid her from ever touching a book again. Instead, he said something that revealed the complex tragedy of their situation. Your grandfather could read Latin and Greek. Did you know that? He was a teacher in Virginia before the war. Lost everything. Came here with nothing.

Spent his last years picking cotton and drinking himself to death because knowing Homer don’t help you when your children are hungry. He turned and walked back to the house, but he never mentioned finding them again. Spring arrived with a gift and a curse. The gift was the arrival of the Moonlight School teachers, part of Kora Wilson Stewart’s revolutionary movement to eliminate adult illiteracy.

The curse was that they only held classes for 2 weeks, and Sarah had to choose between attending and helping plant the cotton that would determine whether her family ate next winter. She chose her family, but James made a secret arrangement with Miss Dorothy Williams, one of the traveling teachers.

He would attend the regular children’s school during the day, then the adult classes at night, memorizing everything to teach Sarah later. The system worked for exactly three nights. On the fourth night, April 8th, 1915, James came home burning with fever.

The epidemic records from the Alabama Department of Public Health show that typhoid fever struck Madison County that spring, spread by contaminated wellwater. Of the 847 cases reported, 294 died. Most were children under 12. James had 6 days to live, though the doctor who finally came on the fifth day said there was nothing to be done except keep him comfortable. Sarah would spend those 6 days by his bedside. And what happened during those final hours would define the rest of her life.

On the evening of April 12th, 1915, as James drifted in and out of consciousness, he became obsessed with teaching Sarah one last thing. His fever had broken temporarily, what doctors called the false recovery that often came before the end. With tremendous effort, he asked for his school slate and chalk. His hands shook so badly that Sarah had to hold them steady.

Together, they wrote five words. Sarah Thompson can read now. He made her promise to keep those words, to copy them every day until she could write them without thinking. It was the last lesson he would ever teach. But James had one more secret, one that Sarah wouldn’t discover until after he was gone. Hidden in his school bag, wrapped in a piece of his mother’s old apron, was a notebook he had been keeping for months.

On every page, he had written the same sentence over and over in his childish hand, practicing until it was perfect. My sister Sarah is the smartest person I know. One day she will read this. Below it, he had begun writing a story about a girl who learned to read and became a teacher. The story was unfinished, ending mid-sentence.

And then Sarah opened her own school and taught all the girls who the rest of the page was blank. waiting for a future that would never come. April 13th, 1915, 3:27 in the afternoon. Sarah would remember the exact time because the courthouse clock was striking as James opened his eyes for the last lucid moment of his life. The typhoid had ravaged his small body for 6 days.

But suddenly, his eyes were clear, focused, and desperately urgent. He gripped Sarah’s hand with surprising strength and whispered words that would echo through the rest of her life. The photograph. Get the photograph. Sarah ran to the trunk where they kept their few valuables and brought back the picture from 2 years ago.

The one of them standing before the schoolhouse. James traced his finger over their faces in the photograph. Then did something that broke Sarah’s heart. He pointed to himself in the picture, then to her and said, “You have to be both now. the one who learns and the one who teaches. His voice was so weak she had to lean close to hear him.

Then with tremendous effort, he took her hand and began tracing letters on her palm, s a r a h, over and over until she realized he was teaching her the most important lesson of all. Her name belonged to her and no one could take it away. The church bells were ringing for evening service when James made his final request.

He wanted Sarah to read to him, not to have someone read to him, but for Sarah herself to read. She picked up his primer, the one they had shared so many secrets over, and opened it to the first page. Her voice shook as she began. The sun rises over the fields. She stumbled over words, had to sound some out slowly, but James smiled with each word she managed.

When she reached the sentence, the boy ran home to his family. James squeezed her hand and whispered, “You’re reading, Sarah. You’re really reading.” They were the last words he ever spoke. James Thompson died at 7:15 that evening, as recorded in the Madison Baptist Church death registry, but before he died, he gave Sarah one more gift. In his final delirium, he kept repeating the same phrase, “Under the loose board.

Under the loose board.” Sarah didn’t understand until after the funeral when she went to the barn and found the loose floorboard beneath where they used to practice reading. Hidden, there was not just one book, but three, all stolen from the school library over months. There was also a note in James’ shaky handwriting for Sarah.

Learn them all, then teach someone else. The funeral was held 2 days later on a morning when late frost had killed all the early blossoms. The Rosenwald Fund records note that the school closed for the day so James’s classmates could attend. His teacher, Miss Foster, approached Sarah after the service with tears in her eyes. She pressed something into Sarah’s hand.

James’s last composition written the day before he got sick. The assignment had been to write about a hero. James had written about Sarah, describing how she worked from before dawn until after dark, how she had saved their mother’s life, how she studied in secret because she was brave enough to want more than the world allowed her to have.

But the most devastating discovery came a week after the funeral. Sarah was cleaning out James’ school things to return them when she found a contract hidden in his arithmetic book. James had made an agreement with Miss Dorothy Williams, the Moonlight School teacher.

In his careful handwriting, he had promised to work for her for free all summer, helping set up chairs and clean school rooms if she would secretly teach Sarah to read. The contract was dated April 7th, 1915, the day before he got sick. He had traded his own summer freedom for his sister’s education, a gift he would never live to give.

Sarah’s grief transformed into something harder and more dangerous, determination. She began rising at 3:00 in the morning to practice reading before her chores. She read the three books James had hidden until she had them memorized. She traced letters in the ash of the fireplace, in the mud by the creek, in the steam on windows. Her father, broken by the loss of his only son, didn’t have the strength to stop her anymore.

Her mother, still weak from her own illness, would sometimes find Sarah asleep over a book and would simply cover her with a quilt and let her sleep. By summer, Sarah could read the newspaper that Mrs. Foster still brought with her laundry.

She discovered that the world was vast and full of injustices she had never imagined. She read about women in New York fighting for the right to vote. She read about children in factories working 14-hour days. She read about schools being built all over the country, but not for girls like her. Each word she conquered was a victory for James, a promise kept to a boy who believed his sister deserved more than the world wanted to give her.

The photograph from 1913 took on new meaning now. Sarah would stare at it in the evenings, seeing things she hadn’t noticed before. The way James was leaning slightly toward her as if protecting her. the way her own hand rested on his shoulder, claiming him as hers to protect in return. The photographer had captured more than two children in front of a school.

He had captured a love that would transcend death, a bond that would drive Sarah forward for the rest of her life. On August 15th, 1915, exactly 4 months after James’s death, Sarah Thompson walked into the general store and asked Mr. Watson if he needed help with his accounts. She could read now, she told him, and she could write numbers. He laughed at first this 13-year-old girl in her patched dress and broken shoes.

But when she picked up his ledger and began reading entries aloud, then caught an error in his arithmetic, he stopped laughing. He offered her three cents a day to help with inventory. But more importantly, he offered her access to something precious, the cataloges and newspapers that came to the store. Sarah Thompson’s education had truly begun.

Built on the foundation of a brother’s love and a photograph that captured the moment before everything changed. Sarah Thompson married at 16 to a man who promised he wouldn’t mind her reading. Thomas Mitchell was a mill worker who seemed kind enough during their courtship, bringing her newspapers from Birmingham and even a book of poetry once.

But marriage revealed his true nature. The first time he found her reading after their wedding, he threw the book into the fire and told her, “No wife of mine is going to put on heirs.” When she tried to hide books, he found them and burned them, too. Madison County marriage records show that between 1918 and 1925, Sarah bore four children and lost two to scarlet fever, all while working 12-hour shifts at the textile mill where she lost two fingers to a mechanical loom in 1924.

But Sarah had learned to be clever from her years of secret education. She memorized entire passages from the Bible during church services, the only reading her husband couldn’t forbid. She taught herself to read upside down so she could read the newspaper on her husband’s table while serving him dinner.

When he died in 1927 from injuries sustained in a mill accident, Sarah mourned the father of her children, but not the man who had tried to crush her spirit. At his funeral, she placed in his coffin the one thing she had managed to hide from him all those years. The photograph from 1913. Knowing he could no longer destroy this last piece of James.

The Great Depression brought Sarah to her knees, but not to defeat, she took in washing, mended clothes, and scrubbed floors. Anything to keep her two surviving daughters fed. But she made a terrible discovery. Her daughters didn’t want to learn to read.

They had watched their mother struggle and suffer for knowledge that brought her nothing but poverty and pain. Mama, her eldest daughter, Ruth, said at 14. Reading never put food on this table. These hands do that. It was the crulest irony of Sarah’s life that she had fought so hard for something her own children rejected. In 1943, Sarah, now 41, heard about a program that would finally change her life.

The WPA adult education initiative was recruiting older women to learn basic literacy to support the war effort. They needed women who could read work orders in the defense plants. Sarah, who could actually read quite well by then, but had no formal certification, enrolled immediately.

On her first day, the 20-something teacher looked at this middle-aged woman with her scarred hands and missing fingers and suggested she might be too old to start learning. Sarah picked up the teacher’s copy of Pilgrim’s Progress and read an entire page aloud without stumbling. She was placed in the advanced class. But the true transformation came when Sarah met Mrs.

Elellanar Hartley, a 65-year-old former school teacher who ran the program. Mrs. Hartley recognized something in Sarah that others had missed. She wasn’t just literate, she was brilliant, held back only by circumstances. She began lending Sarah books from her personal library, introducing her to literature she had never dreamed existed. Sarah discovered that James had been right all those years ago.

She was the smartest person he knew. She just needed someone else to see it, too. The miracle happened in 1963. Sarah, now 61 years old, was working as a janitor at the newly integrated Madison County Public Library when she overheard a conversation that stopped her heart.

The library was starting a program to teach older adults to read, funded by the Kennedy administration’s anti-poverty initiatives. They needed volunteers who understood the shame and struggle of adult illiteracy. Sarah walked into the head librarian’s office and said five words that changed everything. I want to help teach. They gave her a test first. Standard procedure. Sarah scored higher than most high school graduates.

When they asked how a woman with no formal education could read at such a level, she told them about James, about the photograph, about the secret notebook she had found in the barn that she still couldn’t bring herself to read because the pain was too great. The head librarian, Mrs.

Patricia Coleman, whose oral history is preserved in the Alabama Public Library archives, said she had never seen anyone cry so hard while reading aloud as Sarah did that day. Sarah Thompson became the most beloved literacy volunteer in Madison County history. She taught over 200 adults to read between 1963 and 1975. Using methods she had developed from her own painful journey.

She would start each lesson the same way James had taught her, by helping students write their own names. She would tell them, “Your name is yours. Once you can write it, no one can take it away.” She kept the photograph from 1913 on her desk and would point to James and say, “This boy believed anyone could learn to read. He was right.

” On March 15th, 1965, exactly 50 years after James’s death, Sarah finally found the courage to read the notebook he had hidden in the barn. She had carried it with her through marriage, children, widowhood, and poverty, but had never been able to open it. When she finally did, she discovered that James had filled it not just with words of encouragement, but with lessons he was planning to teach her.

He had written out hundreds of words with their definitions, drawn pictures to help her remember them, created simple stories using words he knew she could learn. On the last page, in letters so shaky she knew he must have written them while already sick, were the words, “Sarah will be a teacher someday. I know it.” Sarah lived until 1987, long enough to see her granddaughter Lisa become the first woman in the Thompson family to graduate from college.

At Lisa’s graduation from the University of Alabama, she carried two things, her diploma and the photograph from 1913. In her validictorian speech, she said, “I stand here because a 9-year-old boy believed his sister deserved to read and because that sister never forgot his belief in her.” Sarah, sitting in the front row at 85 years old, touched the notebook in her lap, the one she had finally been able to read, and whispered, “We did it, James.

We both became teachers.” When Sarah died 2 years later, they found she had written a letter to be read at her funeral. In it, she had copied the words James had traced on her palm as he died. S A R A H. Below them she had written, “He taught me that my name was mine. But more than that, he taught me that my mind was mine, too. No one could take that away.

Not poverty, not tradition, not even death. Every person I taught to read was James’s student, too. Every letter they learned was his lesson continuing. The photograph shows two children who loved each other. But it doesn’t show the whole truth. It doesn’t show that love can teach, that sacrifice can transcend death, that a 9-year-old boy can change the world by teaching his sister five letters in the dirt.

James has been dead for 72 years, but every time someone learns to read, he teaches again. This dramatized story inspired by real historical injustices in early 20th century America reminds us that literacy is not just a skill but a form of dignity and that one person’s quiet sacrifice can ignite a lifetime of learning in others.

Love can become a curriculum. Perseverance can turn a closed door into a classroom. What moment in Sarah and James’ journey moved you most? And why? When in your life did someone’s small act of faith open a path you thought was closed? If the right to learn had been denied to you or your family, what tradition or value would you fight to pass forward? If you stayed with us to the end, write the word lamplight in the comments so we know you were here.