In Hidalgo del Parral, where the desert wind drags dust through cobblestone streets and the sun pounds down like a hammer on bare heads, this story is still told.

The old folks know it by heart, like a treasure locked inside their chest. And when nights grow long and the fire crackles low, someone always tells it again—because there are stories that must never be forgotten, no matter how much they hurt the soul like a buried thorn.

Not everyone believes it, they say. But back then there was a politician named Don Matías Ochoa—a man of flowery speech and elegant manners—who strutted across the plaza as if he owned the whole world.

He always carried a silver-tipped cane that gleamed in the sun, wore suits that cost more than a family could earn in a year, and people stepped aside when he passed. Not out of respect, but out of fear. Because Don Matías had the kind of power that fed off the hunger of others.

During years of drought, when the land cracked like dry lips and cornfields withered before they could sprout, aid shipments arrived from the capital—sacks of corn, beans, wheat—meant for families with nothing left to make tortillas. But those sacks never reached the people whole. Don Matías, with the smile of a saint and the heart of a viper, skimmed half of them.

He sold the grain for gold to traders crossing north, or handed it to corrupt generals who paid well to keep quiet.

On Sundays, he filled the San José church with his promises of charity. His voice echoed between the stone columns like holy bells, preaching love of neighbor and aid for the needy. But during the week, his warehouses filled with stolen grain, while mothers boiled bones to feed their children.

He organized rallies in the plaza, giving speeches about honor and hard work, words that sounded sweet like a lullaby—while secretly signing contracts that turned hunger into coins for his pocket.

And the town, though starving, stayed silent. Fear outweighed need. Everyone knew those who spoke too much could end up silenced forever—or disappear into prisons where the sun never shone. His federal soldiers were feared more than wolves, and their rifles enforced a silence heavier than any famine.

But not everyone swallowed the lie. In kitchens, women whispered while grinding meager corn. In cantinas, men drank watered-down pulque and shook their heads with clenched jaws. In the market, honest merchants watched wagonloads of grain head to Don Matías’s warehouses and bit down until their teeth ached.

Don Matías lived in a grand house, gardens watered every morning while the town prayed for rain. His stables overflowed with fat horses, his cellars with enough maize to feed twenty families for a year. His children studied in the capital dressed like princes, while Parral’s children walked barefoot with swollen bellies.

In the afternoons, he sat on his porch smoking Havana cigars, watching people trudge to the wells for water. And sometimes, when a woman came begging for a little corn to make atole for her sick children, he drummed his fingers on his chair and told her lazily:

“Charity only breeds laziness. Better you find work than waste time begging.”

But work was as scarce as rain. The mines shut down by war, ranches broke, cattle stolen by revolutionaries, and the few workshops barely kept their owners alive. Don Matías knew this. And he enjoyed watching despair etch itself into people’s faces.

One dry March afternoon, when the air itself burned like sand, a woman walked slowly into the central plaza.

Doña Luz, widow, thirty but looking fifty from grief. Dressed in black from head to toe, rosary of worn beads around her neck. Her husband Aurelio, a miner, had been killed in an explosion at La Prieta along with five comrades. She was left alone with two children: Toñito, seven, and Carmen, just four.

She survived washing clothes by the river, sewing by candlelight, selling wild greens. But that March was merciless. No rain since November, the river a thin silver thread, the greens dead down to the roots. Her children cried with hunger, she had sold even her wedding shawl for a handful of pinole. All she had left was a few hard tortillas and a pinch of salt.

Gaunt-eyed, cheeks hollow, but spine straight as a fence post, she walked to the government building where Don Matías had just finished meeting American traders. Her children clutched her skirt in silence.

He stepped out laughing, polishing his silver cane. When he saw her waiting, his face soured like spotting a fly in soup. She lowered her shawl from her head respectfully and said:

“Don Matías, forgive the trouble. My children haven’t eaten since yesterday. I beg you, sell me just a piece of bread, even on credit. I swear on the Virgin I’ll pay you back.”

He looked her up and down—patched black dress, shoes worn through, hands cracked from scrubbing in cold water. He saw the desperation in her eyes that hadn’t broken her dignity—and that enraged him.

“Miseries aren’t solved with alms, woman,” he said, cold as iron. “They’re solved with work. I give nothing away. If you want to eat, earn it with the sweat of your brow.”

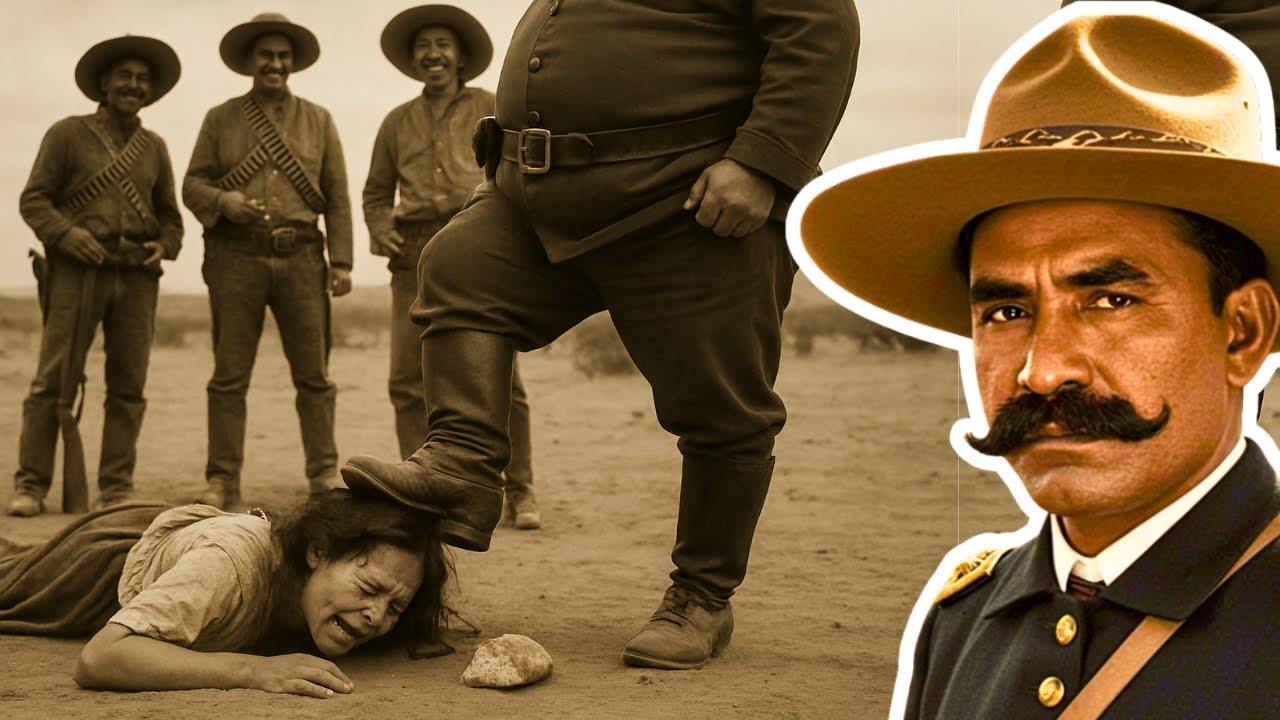

And without warning, he raised his silver cane and struck her across the back. The sound echoed through the plaza.

She bent in pain but did not scream. Her children did—Toñito sobbing, little Carmen confused why the elegant man had hurt her mother. And Don Matías smiled—wolfish, joyless.

“Next time, think twice before whining at me. And take your brats away—they annoy me.”

Doña Luz rose slowly, took her children’s hands, and walked away. The crowd pretended not to see. Some looked at clouds, others hurried home, a few cowards even laughed to win his favor. His soldiers roared with laughter, betting how long before she came crawling again.

She sat at the dry fountain, hugged her children, and cried—for the first time in years. Not from sorrow, but from rage. Rage hot as wildfire.

And that rage carried on the wind. First whispered by a boy selling candles, then to a white-bearded traveler, then to a rider in a dark poncho bound north. And soon enough, into the camp of Francisco Villa.

Villa listened, silent, eyes fixed on the fire. And when the rider finished, he said only:

“What’s his name?”

“Don Matías Ochoa, mi general. And the widow is Doña Luz, with two small children.”

Villa nodded, holstered his pistol, and stared at the horizon where the sun burned red behind the mountains. Fierro, beside him, knew that look: justice was already on its way.

What followed is told in Parral to this day.

The night of Don Matías’s great banquet—while federal colonels and American merchants stuffed themselves on stolen food—Villa appeared in the doorway, quiet as a shadow. Behind him, his Dorados slipped into place. The music died. The laughter died.

And before the richest men in town, Villa called in Doña Luz, dressed in black, rosary in hand, head held high. He raised that same silver cane for all to see.

“Señores,” Villa said, “this is the woman beaten with this cane for daring to ask bread for her children. Tell them, señora.”

And she did, voice clear. Her words cut sharper than blades.

Then Villa turned to Don Matías:

“Kneel.”

And the man who strutted like a king an hour earlier now trembled, knees hitting the floor, begging forgiveness before the widow he had humiliated.

That night, under Villa’s command, Don Matías carried sack after sack of grain to the plaza, handing them with blistered hands to the hungry families of Parral. One by one, until dawn.

And as the people watched, they learned a truth burned into memory:

Power exists not to crush the weak, but to protect them.

The old ones still tell it: in Parral, when Villa came, the proud politician who had beaten a widow was the one left kneeling in the dust, begging for mercy.