The antique shop on Maple Street had been calling to Sarah for weeks. Every morning on her way to the university library, she’d slow her pace as she passed the dusty windows filled with forgotten treasures. Today, something made her stop completely. A small ornate picture frame caught the autumn sunlight streaming through the glass.

The photograph inside showed a young girl, maybe 8 or 9 years old, sitting in what appeared to be a Victorian parlor. The girl wore a white dress with delicate lace trim, her dark hair pulled back with a ribbon. But it was her smile that drew Sarah closer to the window, a bright, genuine expression of pure joy that seemed to radiate warmth even through the old glass.

Sarah pushed open the shop door, setting off a chorus of windchimes hanging from the ceiling. The elderly shopkeeper looked up from behind a counter cluttered with pocket watches and jewelry boxes. That photograph in the window, Sarah said, pointing back toward the street. The one with the little girl.

Do you know anything about it? The man adjusted his wire rimmed glasses and shuffled toward the window display. Ah, yes. Found it in an estate sale up in Milbrook last month. Beautiful piece, isn’t it? The frame solid silver, probably worth more than the photograph itself. Sarah studied the image more closely. The girl’s pose was formal, as was typical for photography of that era, but her expression was anything but stiff.

There was something almost modern about her smile, as if she knew a wonderful secret. “How much?” Sarah asked. $40 for the frame and photograph together. It was more than Sarah usually spent on impulse purchases, but something about the girl’s face made the decision easy. She handed over the money and carefully carried her new acquisition back to her small apartment near campus.

That evening, Sarah placed the photograph on her desk next to her laptop. She was working on her thesis about early 20th century American photography, and the image seemed like perfect inspiration. As she typed, she found herself glancing at the girl’s face, drawn again and again to that radiant smile.

It wasn’t until she was preparing for bed that she really looked closely at the photograph for the first time since bringing it home. Under the warm glow of her desk lamp, details became clearer. The girl sat in a highback chair, her hands resting in her lap. Her white dress was beautifully detailed with tiny buttons running up the front and intricate embroidery along the sleeves.

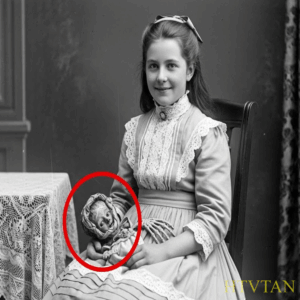

Sarah leaned closer, squinting at the image. Something seemed different about the girl’s hands. At first glance, they appeared to be simply folded in her lap, but there was an odd shadow between her fingers. She pulled out a magnifying glass she used for examining old documents and held it over the photograph.

Her breath caught in her throat. The girl wasn’t just sitting with her hands folded. She was holding something, something small and pale that Sarah had initially mistaken for part of her dress. As she adjusted the angle of the magnifying glass, the object became clearer. It was a doll, a tiny porcelain doll with dark hair and a white dress that perfectly mirrored the girl’s own outfit.

But there was something wrong with the doll’s face. Where there should have been painted features, there appeared to be tiny dark holes where eyes should be and what looked like a crack running down one side of its head. Sarah sat down the magnifying glass and rubbed her eyes. She was probably just tired, seeing details that weren’t really there.

Old photographs often had imperfections, spots and shadows that could look like almost anything if you stared long enough. But when she looked again, the doll was still there. She spent the next hour researching Victorian photography techniques online, trying to understand how shadows and light might create the illusion she was seeing.

Everything she read suggested that her first instinct was probably correct. Old photographs were notorious for creating false images through deterioration and poor lighting conditions. Still, she couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something deliberately unsettling about the doll in the girl’s lap. The next morning, Sarah brought the photograph to her adviser, Professor Williams, who specialized in historical photography analysis.

His office was filled with examples of 19th and early 20th century images. And if anyone could explain what she was seeing, it would be him. Interesting piece, he said, examining the photograph through his own magnifying equipment. The quality is quite good for 1905 based on the style and composition. Professional work, I’d say. Probably a family portrait.

What do you make of what the girl is holding? Sarah asked. Professor Williams spent several minutes studying the image. It appears to be a doll of some kind. Quite common for children’s portraits of that era. Parents often included toys or cherished possessions to help the child remain still during the long exposure times.

But doesn’t something seem off about it? The face specifically. He looked again, adjusting the focus. Well, doll making in the early 1900s wasn’t always as refined as modern techniques. Many cheaper dolls had rather crude facial features, and photography of that era often made small details appear distorted or unclear. Sarah nodded, but his explanation didn’t fully satisfy her.

There was something about the doll that seemed intentionally disturbing, not just poorly made or badly photographed. That afternoon, she decided to visit the Milbrook Historical Society, hoping to learn more about the photograph’s origins. The town was about an hour’s drive north of the university, nestled in a valley surrounded by hills that were just beginning to show their autumn colors.

The historical society occupied a converted Victorian house on the main street. Sarah found the curator, Mrs. Patterson, organizing files in a back room filled with cardboard boxes and filing cabinets. “I’m trying to learn about a photograph that was recently sold at an estate sale here in town,” Sarah explained, showing her the image.

Do you recognize the girl or the setting? Mrs. Patterson studied the photograph carefully, her expression growing thoughtful. The dress style and photographic technique certainly fit with our local history from that period. Many of the wealthier families in Milbrook had formal portraits taken around 1905. She led Sarah to a wall covered with historical photographs of the town and its residents.

We have quite a collection from that era. The Ashford family, the Morganss, the Blackwoods, all the prominent families commissioned professional photographers for their children. Sarah scanned the photographs looking for any similarities to her image. Most showed formally dressed children in similar poses, but none had the same warmth in their expressions as her smiling girl.

“Actually,” Mrs. Patterson said slowly, “There is something familiar about this particular photograph. The background setting, that wallpaper pattern and the style of chair looks very much like the interior of the old Witmore House. Whitmore House. It was one of the grandest homes in Milbrook back then, built in the 1880s by Jonathan Whitmore, who made his fortune in textiles.

The family lived there until the 1920s when they moved to Boston. After she paused, seeming to reconsider her words. After what? Mrs. Patterson looked uncomfortable. There were some tragedies in the family. Nothing unusual for that era. You understand? Child mortality was much higher then and families often faced multiple losses.

What kind of tragedies? Well, the Witmores had several children but only one survived to adulthood. The others died of various illnesses. Influenza, scarlet fever, the usual culprits. It was heartbreaking but unfortunately common. Sarah felt a chill run down her spine. Do you know which children died or when? I’d have to check our records, but I believe there was a daughter who passed away in 1905 or 1906.

She would have been quite young, maybe eight or nine years old. The description matched the girl in the photograph perfectly. Sarah asked if she could examine the historical records, and Mrs. Patterson agreed to help her search through the files. They spent the next 2 hours going through boxes of documents, obituaries, and family records.

Finally, in a folder labeled Witmore family, 19001910, Sarah found what she was looking for. The obituary was brief, as was typical for the time. Miss Catherine Witmore, beloved daughter of Jonathan and Margaret Witmore, passed away November 15th, 1905 after a brief illness. She was 9 years old. Services will be held at First Presbyterian Church, but it was the accompanying photograph that made Sarah’s hands tremble.

It was clearly the same girl from her portrait, wearing the same white dress with the same dark hair and ribbon. The only difference was that this photograph showed her lying in what appeared to be a small white coffin, her hands folded over her chest. It was a post-mortem photograph, a common practice in the Victorian era when families wanted a final image of deceased loved ones. “Oh my,” Mrs.

Patterson said softly. “I hadn’t realized this was a memorial portrait.” Sarah stared at the two photographs side by side. The girl in her picture was definitely alive when it was taken. Her eyes were open, her smile genuine, but according to the records, Catherine Whitmore had died in November 1905, and the photographic style suggested her portrait had been taken around the same time.

“Is it possible this portrait was taken shortly before she died?” Sarah asked. “Certainly.” Many families commissioned formal portraits when children became ill, knowing they might not have another chance. But that didn’t explain the unsettling feeling Sarah got every time she looked at the doll in Catherine’s lap. Now knowing the girl had died shortly after the photograph was taken, the image seemed even more disturbing. Mrs.

Patterson helped her make copies of the historical documents, and Sarah drove back to the university with more questions than answers. That evening, she spread everything across her desk, the original photograph, copies of Catherine’s obituary and post-mortem image, and her research notes. Under her desk lamp, she examined the doll in Catherine’s lap once again.

With the magnifying glass, she could see that it wasn’t just poorly made or damaged. The doll’s face appeared to have been deliberately altered. The eyes had been carved out, leaving dark holes, and the crack she’d noticed earlier looked more like a deliberate cut than accidental damage.

More disturbing was a detail she hadn’t noticed before. The doll’s white dress, which she’d thought mirrored Catherine’s outfit, actually seemed to be stained. Dark spots covered the fabric, particularly around the chest area. In the black and white photograph, it was impossible to tell what the stains were, but they had a disturbing quality that made Sarah’s stomach turn.

She tried to research the significance of dolls in Victorian morning practices, thinking perhaps the damaged doll had some ceremonial purpose. What she found was even more unsettling than she’d expected. In some families, children’s toys were deliberately damaged or altered when the child died, symbolically killing the objects so they could accompany the deceased to the afterlife.

More disturbing were accounts of parents who would dress dolls to look like their deceased children, creating memorial objects that helped with the grieving process. But Sarah’s research uncovered something even stranger. In a few documented cases, families reported that dolls belonging to deceased children would appear to move or change position as if the child’s spirit was still playing with them.

These accounts were usually dismissed as griefinduced hallucinations, but they were remarkably consistent across different regions and time periods. As the night grew later, Sarah found herself unable to stop staring at Catherine’s photograph. The girl’s smile, which had initially seemed so joyful and alive, now appeared almost knowing, and the doll in her lap seemed to be staring back despite its gouged out eyes.

She was about to close her laptop when she noticed something that made her blood run cold. The photograph on her desk looked different, not dramatically. It was subtle enough that she might have missed it if she hadn’t been staring at the image for hours. The doll’s head was turned slightly to the left.

She was certain it had been facing forward before. Sarah grabbed the magnifying glass and examined the image closely. She tried to tell herself it was just a trick of the light or fatigue playing tricks on her perception. But no matter how she looked at it, the doll’s position had definitely changed. She took out her phone and snapped a picture of the photograph, then compared it to others she’d taken earlier in the day.

There was no doubt about it. The doll had moved. Over the next several days, Sarah became obsessed with documenting the changes in the photograph. She set up a time-lapse camera to monitor it continuously, but the device seemed to malfunction whenever anything significant happened. She’d find hours of footage missing, or the image would be too blurry to make out details.

But with her own eyes, she witnessed undeniable changes. The doll would turn its head or shift position in Catherine’s lap. Sometimes its damaged face would seem to be looking directly at Sarah despite having no eyes. More disturbing were the changes in Catherine herself. Her smile, which had initially appeared so genuine and happy, began to look forced.

There were days when her expression seemed sad, almost pleading, and her eyes, which had sparkled with life and mischief, began to look hollow and desperate. Sarah tried to research similar phenomena online, but most of what she found were obvious hoaxes or stories with no credible documentation. She considered taking the photograph to other experts.

But how could she explain that an image from 1905 was somehow changing before her eyes. The breakthrough came when she discovered a collection of letters in the university archives donated by a descendant of the Witmore family. Among them was correspondence between Catherine’s parents in the months following her death.

Jonathan Whitmore had written to his brother in Boston. Margaret refuses to accept that Catherine is gone. She insists the child still plays with her dolls and claims to hear her voice in the nursery at night. I fear grief has affected her mind. The doctor suggests we remove all of Catherine’s possessions from the house, but Margaret will not hear of it.

Margaret Whitmore’s own letters were even more revealing. Catherine comes to me in dreams, but they feel more real than waking. She tells me she is cold and lonely and asks why I let them put her in the ground. She shows me her doll, the one we buried with her, and it is broken and dirty. She asks me to fix it, but I cannot reach her.

Jonathan thinks I am losing my sanity, but I know my daughter. I know when she is near. The final letter in the collection was dated December 1905, just 1 month after Catherine’s death. I have commissioned Mr. Hayes to create a memorial portrait of Catherine using the formal photograph we had taken just before she became ill. But something is wrong with the image he has produced.

Catherine’s expression looks different from the original. And the doll in her lap, the same doll we buried with her, appears damaged in ways I do not remember. Mister Hayes insists he has not altered the photograph, but I cannot shake the feeling that Catherine is trying to tell me something through this image.

I have decided to keep the portrait despite Jonathan’s objections. Perhaps it will bring me comfort, or perhaps it will help me understand what my daughter needs. Sarah realized that her photograph was the same memorial portrait Margaret Whitmore had commissioned. But if the original photograph had been taken before Catherine’s death and the memorial version was created afterward, why did the doll appear damaged in the memorial but not in the post-mortem photograph? She returned to the historical society to examine the post-mortem image more

closely. Mrs. Patterson helped her access a highresolution scanner that could capture details invisible to the naked eye. When they examined the post-mortem photograph under magnification, Sarah’s theory was confirmed. Catherine was indeed holding a doll in death, but this doll appeared perfect, unmarked, with painted features intact and a clean white dress.

It’s as if two different dolls were photographed, Mrs. Patterson observed. Or the same doll at different times, Sarah said quietly. That night, Sarah sat in her apartment staring at the memorial portrait. Catherine’s smile had faded almost entirely now, replaced by an expression of profound sadness. The doll had turned to face outward, its hollow eye socket seeming to plead with anyone who would look.

Sarah finally understood what she was witnessing. Catherine Whitmore had been buried with her beloved doll. But in the year following her death, something had gone wrong. The child’s spirit was trapped, unable to rest because her cherished companion had been damaged or destroyed in the grave. The memorial portrait wasn’t just a static image.

It was somehow connected to Catherine’s restless spirit. allowing her to communicate across more than a century of time. The changing photograph was the girl’s desperate attempt to show what had become of her doll, and by extension, what had become of her. Sarah made a decision that might have seemed insane to anyone else, but felt completely logical to her.

She was going to help Catherine Whitmore find peace. The next morning, she drove back to Milbrook and located the old cemetery where the Witmore family was buried. Catherine’s grave was marked by a small white headstone with a carved lamb, a common symbol for children’s graves in that era. Sarah knelt beside the grave and spoke aloud, feeling foolish but somehow certain she was being heard.

Catherine, I see your doll is broken. I understand you’re trying to show me what happened. I want to help you. She pulled the memorial portrait from her bag and placed it against the headstone. I’m going to find you a new doll, one that looks just like your old one, and I’m going to leave it here with you, so you won’t be alone anymore.

The drive to the antique district in the city took 2 hours, but Sarah was determined to find the right doll. She visited shop after shop, looking for a porcelain doll that matched the one in Catherine’s photograph. Most were too modern or the wrong size or had features that didn’t match what she remembered from the original image.

Finally, in a dusty shop specializing in Victorian era toys, she found what she was looking for. The doll was almost identical to the one Catherine had been buried with. The same dark hair, the same white dress with tiny buttons, even similar facial features. The shop owner mentioned that it had been made around 1905, making it authentic to Catherine’s time period.

Sarah purchased the doll and drove directly back to the cemetery. Evening was approaching, casting long shadows across the old headstones. She placed the new doll carefully on Catherine’s grave, arranging its dress and positioning its arms the same way Catherine had held her original doll. “Here,” she said softly.

“This one is perfect, and it’s just for you. You don’t have to be lonely anymore.” As she spoke, Sarah felt a subtle shift in the air around her. Not quite a breeze, but a sense of movement and presence. The temperature seemed to drop slightly, and she had the distinct impression that she was no longer alone in the cemetery.

But instead of fear, she felt a profound sense of peace settle over the grave site. The oppressive sadness that had seemed to emanate from Catherine’s memorial portrait was lifting, replaced by something that felt like gratitude and relief. Sarah returned home as the sun was setting. She went directly to her desk, where Catherine’s memorial portrait still sat under the desk lamp.

The change was immediately apparent. Catherine’s smile had returned, brighter and more genuine than ever before. Her eyes sparkled with the same joy and life that had first drawn Sarah to the photograph, and the doll in Catherine’s lap was perfect once again, unmarked, whole, with painted features intact, and a clean white dress.

It looked exactly like the new doll Sarah had left at the grave. Over the following weeks, the photograph remained constant. Catherine’s expression never changed again. She looked eternally happy, holding her perfect doll in a moment of pure childhood joy, frozen in time. Sarah kept the portrait on her desk as she finished her thesis, finding comfort in the girl’s peaceful smile.

Months later, when Sarah returned to visit Catherine’s grave, she found that the doll she’d left had weathered beautifully. Despite exposure to rain and snow, it remained remarkably intact, as if something was protecting it from decay. Fresh flowers appeared regularly on the grave. Other visitors, perhaps descendants or local historians who felt drawn to remember the young girl who had died so long ago.

Sarah never learned exactly how the memorial portrait had been connected to Catherine’s spirit, or why the girl’s distress had manifested through changes in the photograph, but she understood that some bonds between a child and her cherished toy, between the living and the dead, between those who suffer and those who offer comfort, transcend the normal boundaries of time and space.

The photograph now sits in Sarah’s office at the university where she has become a professor specializing in Victorian photography and memorial practices. Students often comment on the beautiful portrait of the smiling girl, noting how alive and happy she appears. Sarah always agrees, but she never tells them the full story of Catherine Whitmore and her doll.

Some stories, she has learned, are best preserved in the quiet spaces between the living and the dead, where love and compassion can heal wounds that time alone cannot