There are photographs that capture moments. And then there are photographs that shouldn’t exist at all. In 1912, a team of botonists from the University of Pittsburgh ventured deep into Blackwood Forest in Pennsylvania. Their mission was simple. Document a rare species of fern thriving in the untouched wilderness.

The forest was isolated, barely mapped, known only to loggers and the occasional scientist willing to navigate its dense, twisted paths. Among the dozens of silver gelatin prints they produced that summer, one image stood out for being utterly unremarkable. Plate 27, an empty trail. Nile trees clawing toward a pale sky.

Weak sunlight barely filtering through the canopy. Nothing more. It was filed away with a handwritten note. Blackwood flora survey plate 27. Unremarkable. For over a century, that photograph sat in the archives of the Smithsonian Institution, forgotten among thousands of botanical records until 2020. Dr.

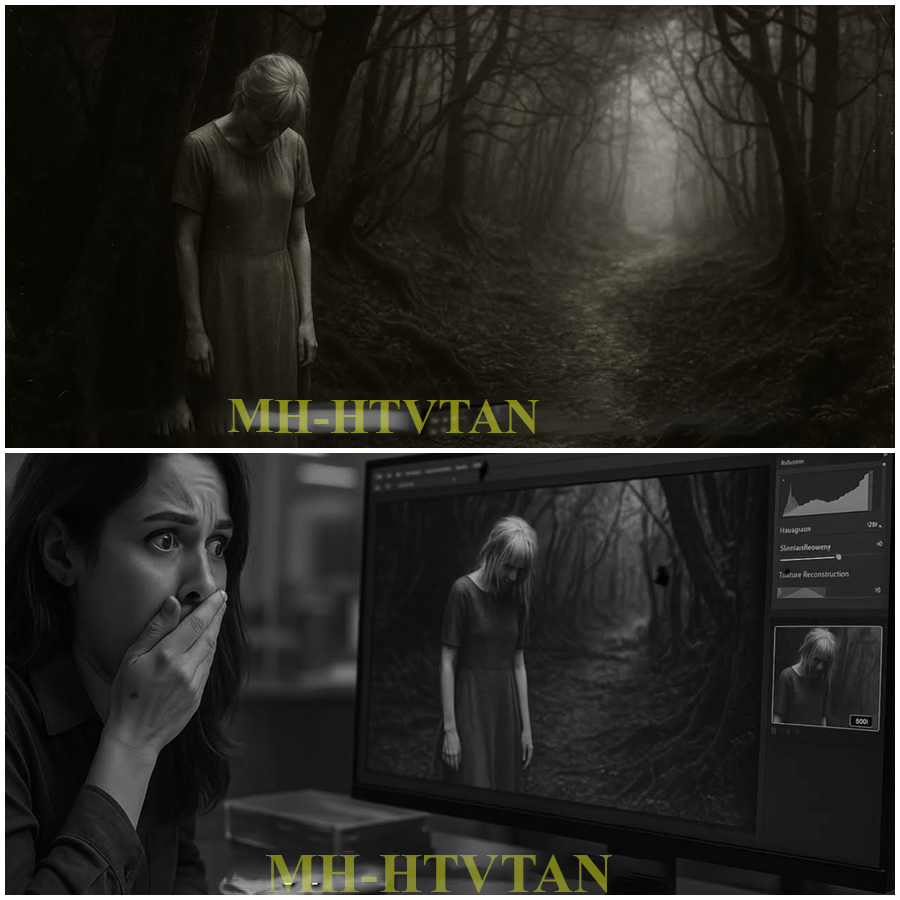

Helena Navaro, a restoration specialist with over 15 years of experience preserving antique negatives, was working through a massive digitization project when she came across the Blackwood collection. Her job was methodical. Scan each plate at 4,800 dpi. Recover shadow details. Enhance exposure levels. Reconstruct light balances that time had eroded.

When she processed plate 27, something changed. At first, Helena thought it was a scanning error, a smudge, a chemical defect in the emulsion.

But as the digital restoration peeled back layers of shadow and light, a figure began to emerge in the left corner of the frame, a woman. She wasn’t there in the original print. Helena compared them side by side. The physical photograph showed nothing but trees and an empty path, but the digital file extracted directly from the glass plate negative revealed her clearly.

The woman stood partially obscured by shadow, as if she had been hiding in a part of the forest the 1912 exposure hadn’t fully captured. But that didn’t make sense. The cameras used in that era required long exposures. If someone had been standing there, even for a second, they would have appeared as a blur.

This woman was perfectly still, perfectly clear. Helena zoomed in. The woman’s hair was light colored, pulled back but disheveled, strands hanging loose around her face. Her skin was unnaturally pale, almost luminous against the dark trees. And her clothing, it didn’t match the era. The fabric looked synthetic, smooth, with a sheen that didn’t exist in 1912 textiles.

The style was something from the 1960s, maybe the 1980s. A simple dress, slightly worn. Her posture was wrong, too. Her head hung low, chin almost touching her chest. Her arms dangled limply at her sides. Her body was rigid, frozen midstep in a way that defied the physics of motion blur. And beneath her feet, nothing, no shadow, not even the faintest outline where sunlight should have been blocked by her form. Helena ran the scan again.

Same result. She brought in colleagues. They examined the negative under magnification, checked for double exposures, chemical contamination, modern tampering, nothing. The woman was embedded in the original emulsion, captured in 1912, invisible to the naked eye, but recorded nonetheless. And then someone noticed the path she was standing on.

According to forestry records, that trail didn’t exist in 1912. It was officially cleared and marked by the Pennsylvania Forestry Commission in 1944, 32 years after the photograph was taken. Helena published her findings in a conservation journal, expecting academic debate. Instead, the image went viral. Within days, tens of thousands of people were analyzing every pixel, offering theories, demanding explanations, and then a message arrived that changed everything.

It came from a genealogologist named Martin Crowe, specializing in missing persons cases from the early 20th century. He’d seen the restored photograph, and he recognized the woman. Her name was Elellanena Witmore. Born in 1884 in rural Pennsylvania, Elellanena was the daughter of a minor landowner with deep ties to the coal industry.

She’d grown up fascinated by the natural world, unusual for a woman of her social standing. By her early 20s, she’d become an informal assistant to several university botonists, accompanying them on fieldwork, despite her family’s objections. In the spring of 1908, Elellanena joined a small expedition into Blackwood Forest.

The goal was to map uncharted flora in the region’s interior. She was the only woman in the group, serving as an illustrator and specimen collector. 3 days into the expedition, Eleanor vanished. The men she was traveling with reported that she’d left camp early one morning to sketch a grove of old growth hemlocks. When she didn’t return by midday, they organized a search.

For 2 weeks, they combed the forest. They found nothing. No body, no belongings, no trace. Her disappearance was ruled an accident. Wild animals, a fall, the forest swallowing her whole. Her family held a memorial service with an empty casket. And Elellanena Whitmore became another name in the long list of people who walked into the wilderness and never came back until 2020 when she appeared in a photograph taken 4 years after she died. Helena couldn’t let it go.

She contacted the National Park Service, local historians, anyone with knowledge of Blackwood’s history. Together, they organized an expedition to the exact location where Plate 27 had been photographed. Using GPS coordinates, sun angle calculations, and comparisons with surviving vegetation, they pinpointed the spot.

It took 3 days of hiking through dense undergrowth, but they found it. The trail was still there, overgrown now, barely visible, but unmistakable when you knew what to look for. And just off the path, hidden beneath a century of leaf rot and moss, they found something else. a structure, an old wooden shelter, little more than a collapsed leanto, half buried in the earth.

Inside they found a mother of pearl comb cracked but intact, a broken chain tarnished silver with traces of an engraved pattern, remnants of a wool coat, heavy fabric rotted to threads, but distinctly early 1900s in style, and a leatherbound journal. Its pages nearly destroyed by moisture and time. Most of the writing was illeible, but on one page, barely visible, they found initials carved into the leather cover.

EW Elellanena Witmore had been there, not in 1912. Not when the photograph was taken, but sometime before or after or during time itself seemed to bend around the clearing. Helena brought the journal back to her lab. Using infrared imaging, she managed to recover fragments of text.

Most of it was scientific observations. plant species, weather patterns, sketches of fungi. But near the end, the tone shifted. The handwriting became erratic, desperate. One entry, dated May 17th, 1908 read, “I cannot find the way back. The others are gone. The forest has changed. I no longer recognize the paths. Something is wrong with the light here.

It does not move as it should.” Another entry, undated. I saw them today. Men with strange instruments. They did not see me. I called out. They did not hear. And the final legible line, “If anyone finds this, tell them I tried. Tell them I am still trying.” Helena didn’t sleep for 3 days after reading those words.

She kept returning to the restored photograph, studying Eleanor’s frozen posture, her lowered head, the absence of her shadow. And then she remembered the Blackwood collection contained over 200 glass plate negatives. She’d only processed a fraction of them. She went back to the archives.

This time she requested every single plate from the 1912 expedition. For weeks she scanned them methodically, one by one, searching for anything unusual. Most were exactly what they should be. Ferns, tree bark, soil samples, and then near the end of the collection, she found it. Plate 194. It had never been cataloged. There was no entry in the expedition logs, no label on the sleeve, just a dusty glass negative tucked into the back of a storage box as if someone had meant to file it away and forgotten.

Helena scanned it. The image showed the same location as plate 27. The same twisted trees, the same pale light, but this time Elellanena wasn’t in the shadows. She was standing in the center of the frame, close, impossibly close, as if she’d walked toward the camera after the first photograph was taken.

Her face was fully visible now, pale, gaunt, eyes wide, and staring. Not at the trees, not at the forest, directly at the lens, directly at whoever was looking at her, as if she knew, as if she’d been waiting. If you want to see more stories like this, subscribe to the channel so you don’t miss the next ones because this is just the beginning.

Helena examined the image for hours. Elellanena’s expression wasn’t fear. It wasn’t confusion. It was something else. Recognition, awareness, like she understood in that moment that someone would eventually find her, that someone would eventually see. Forensic analysis confirmed the plate was authentic. The emulsion matched samples from 1912.

The negative had never been tampered with, never been exposed to modern chemicals. It was original, real. But Elellanena Whitmore disappeared in 1908, 4 years before this photograph was taken. Helena submitted her findings to three separate laboratories. All of them reached the same conclusion. The image was genuine.

No forgery, no manipulation. Elellanena Whitmore appeared in a photograph taken 4 years after her death in a location she’d vanished from, staring directly at the camera as if she’d been waiting a century for someone to notice. The question isn’t whether the photograph is real. The evidence confirms it is.

The question is what Elellanena was trying to tell them. Why she appeared not once but twice. Why she moved closer. Why she looked directly at the lens. Some researchers believe the forest itself is responsible. Blackwood has a history of strange occurrences, compasses malfunctioning, hikers reporting lost time, sounds that don’t match any known animal.

But that doesn’t explain Elellanena. It doesn’t explain how a woman who died in 1908 appeared in 1912 wearing clothes from decades later standing on a path that didn’t exist yet. Others think it’s a temporal anomaly, a crack in the fabric of time, localized to that one clearing deep in the Pennsylvania wilderness, that Elellanena somehow became trapped in a loop, reliving the same moment over and over, trying to signal for help across the years.

Helena Navarro has a different theory. She believes Elellanena never left, that she’s still there somewhere in Blackwood Forest, caught between moments, trying to communicate the only way she can, through light, through shadow, through the imperfect chemistry of silver and gelatin, waiting for the right technology, the right person to finally see her.

The Smithsonian has sealed the rest of the Blackwood collection. No more plates will be scanned. No more images will be restored. Officially, it’s due to preservation concerns. But Helena knows the truth. There are more photographs, dozens of them. And if Elellanar moved closer between plate 27 and plate 194, what happens in the ones that were taken after? How close does she get? What does she want? 3 months ago, a hiker went missing in Blackwood Forest.

A woman in her 30s, experienced, well equipped. Search teams found her camera a week later near the clearing where Elellanena’s shelter had been discovered. The memory card was corrupted, unreadable except for one image. A selfie taken at dusk. The woman smiling and behind her just barely visible in the shadows between the trees.

A pale figure, light hair, dark eyes watching. The search was called off after 2 weeks. No body was ever found. Late 194 remains in the Smithsonian archives, sealed in a climate controlled vault. But sometimes late at night, Helena still looks at the scans she made. She zooms in on Elellanena’s face on those wide staring eyes. And she wonders if Elellanena is still waiting, still watching, still moving closer.

Because if there’s one thing Helena learned from restoring that photograph, it’s this. Some images don’t just capture the past. They capture something that refuses to stay there.