May 28th, 1940. 15 hours. The cabinet war rooms, London. The air is thick with cigar smoke, sweat, and the metallic taste of fear. Winston Churchill, his face of Bulldog’s mask of defiance, paces the floor. The news from France is not just bad. It is apocalyptic. The British expeditionary force is trapped. The evacuation at Dunkirk has begun.

A desperate gamble to save a broken army. France is collapsing. Belgium has surrendered. Holland is crushed. Norway is lost. Britain stands alone. A small island against the seemingly invincible Nazi war machine that has conquered all of Europe in a matter of weeks. The German high command is finalizing plans for Operation Sea Lion.

The invasion of Great Britain. The conventional war. The war of gentlemen of battle lines and declared fronts is over. And Britain has lost. As the bombs of the Blitz begin to fall, tearing the heart out of London, Churchill convenes a secret meeting. He looks at his new minister of economic warfare, Hugh Dalton.

We must, Churchill growls, his voice a low rumble. Prepare for a new kind of war, a war of attrition, a war of nerve. The old rules are dead. The Marquis of Queensbury rules do not apply when fighting a rabid dog. The British army, what’s left of it, can defend the beaches, but it cannot free Europe. Not like this. Churchill has a new desperate idea.

An idea born of insurgency, of back alley fighting, of terror. He needs an organization that will operate in the shadows. Men and women who can move like ghosts inside Hitler’s fortress Europe. They will not capture territory. They will create chaos. They will link up with local resistance. They will arm them. They will train them.

They will blow up bridges, assassinate generals, derail supply trains, and destroy factories. They will be a cancer eating the Third Reich from within. On July 19th, 1940, Churchill gives Dalton a simple terrifying directive. He scrolls a note. And now, set Europe ablaze. From this order, a new clandestine organization is born.

the special operations executive or SOE. Its purpose is so secret it is known to only a handful of men. Its mission to coordinate all action by way of subversion and sabotage against the enemy overseas. It is in short a ministry of ungentlemanly warfare. But there is one catastrophic problem. The idea is brilliant, but the reality is impossible.

Britain has no one to do this. The British military is trained to march in formation, to fire rifles in volleys, to fight on a battlefield. They are not trained to pick locks, crack safes, build bombs out of household flour, or kill a man in silence with a piece of piano wire. Where do you find teachers for an art that doesn’t officially exist? Where do you train these new agents without German spies? Just across the channel, seeing and reporting everything.

The SOE is created, but it is an empty shell. It has a mission but no means. The generals of the Allied high command are stumped. They need a solution and they need it yesterday. They cannot believe where the solution will come from. It will not come from the ancient halls of Oxford or the parade grounds of Sandhurst.

It will come from a quiet, unassuming farm thousands of miles away on the other side of the Atlantic. It will come from Canada. The solution has a name, William Stevenson. To the world, he is a mildmannered Canadian industrialist, a wealthy businessman from Winnipeg to Churchill and secretly to President Roosevelt.

He is the man cenamed Intrepid. Stevenson is a new breed of power broker. He is a genius, a World War I flying ace, a millionaire, and the quiet center of a web of influence that spans the globe. He is Churchill’s personal clandestine link to Washington, operating long before America enters the war. His official title is British passport control officer, a laughably transparent cover.

His real job is to run all British intelligence operations in the entire Western Hemisphere. Little Bill Stevenson understands the problem better than anyone. He knows the SOE needs a school, but he knows that school cannot be in Britain. It’s too small, too exposed, too crawling with spies. He needs a place that is secure.

He needs a place that is discreet. He needs a place with access to raw materials, both for explosives and for people. He needs a place close enough to the neutral United States that he can begin to secretly train the Americans, who he knows will soon be dragged into this fight and have even less of an idea of how to conduct espionage than the British.

In the winter of 1940, Stevenson makes a proposal to the Canadian government. He doesn’t ask for an army base. He asks for a piece of land. The location he chooses is perfect in its obscurity. It is not a fortress. It is not a compound. It is a farm, a 200 acre plot of unremarkable, scrubby farmland just outside the quiet industrial town of Ashawa, Ontario.

It borders the cold, gray, rolling waves of Lake Ontario. It’s surrounded by a few gullies and a bit of forest. To any passer by is just another Canadian farm, its fields lying for the winter. The Canadian Prime Minister, McKenzie King, agrees. On one condition, total absolute secrecy. The Canadian public and even the Canadian Parliament must never know about it.

The RCMP, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, will provide a security perimeter, but that’s it. The project is given a sterile bureaucratic code name designed to be forgotten, STS 103. Special training station 103. The men who will be sent there, however, will give it another name, a name that will become legend, whispered in the intelligence communities for the rest of the century.

They will call it Camp X. In early December 1941, just as the world is reeling from the news of Pearl Harbor, Campex quietly opens its gates. From the outside, it is nothing. A few newly constructed wooden barracks, a flag pole, and a barbed wire fence. The main building is the original farmhouse, the Whitby farm, a simple brick and wood structure.

It looks like a minor military signaling post. The guards tell any curious local farmers or police that it’s a special driver’s training school. That is the official lie. The reality is is something else entirely. The Allied High Command, desperate for a solution, has placed its faith in Stevenson’s secret farm.

They still cannot believe this is the answer. It is. Until the first instructors arrive, and the generals realize this farm is not going to be a school. It is going to be a factory. A factory for producing the most dangerous human beings the world has ever seen. The men who arrive to teach at Campex are not soldiers. They are by all gentlemanly standards, thugs.

They’re killers. They are the living masters of a forbidden art. The SOE scour the globe for the most lethal, unconventional minds they can find. And they find them. The most important is a man named William Uertitt Fairbann. Fairbann is a legend in the Shanghai Municipal Police, the most dangerous to crimeridden city on earth.

For decades, he had fought a daily war against the triads, against kidnappers, against street gangs. He’s a small, quiet, pespected man who looks like a librarian. He is perhaps the most dangerous man alive. He has developed his own system of combat, defundu. It is not a sport. It is not for honor. It is the science of winning a life ordeath fight in seconds.

It is about maximum damage, minimum time. It is about killing. He teaches how to kill with a fountain pen, a rolledup magazine, a teacup. His motto, get tough, get down, and get it over with. With him is Eric Bill Sykes. Sykes is Fairband’s partner in chaos, a firearms expert, and the co-designer of the most iconic and most terrifying weapon of the war, the Fairband Sykes Commando knife.

This knife is not a tool. It is not a utility blade. It is designed for one purpose and one purpose only. To kill a man. Its long, thin, stiletto blade is designed to penetrate the ribs, to puncture the lungs, the heart, the kidneys, and be withdrawn, leaving almost no external wound, but catastrophic internal damage.

It is a weapon of assassination. And here on this quiet Canadian farm, Sykes and Fairburn are now the headmasters. This is the curriculum the Allied generals could not believe. There is no marching. There is no saluting. The first class is silent killing. Fairb in his quiet British accent would stand before a class of rough Canadian lumberjacks, French Canadian trappers and American college boys.

And he would teach them how to snap a man’s neck. He would teach them the tiger claw, a handstrike to the throat. He would teach them how to use a piano wire gar. He would teach them how to walk up behind a sentry, cup his helmet, and use the steel rim to sever his spinal cord. They are taught to be, in a word, ungentlemanly.

This secret farm in Ontario is not just training soldiers. It is untraining them. It is systematically breaking down every instinct of a fair fight. It is teaching them to be the very thing they were sworn to destroy. It is teaching them to be assassins, and the training has only just begun. The lessons in silent killing were not an academic exercise.

They were a visceral, hands-on rejection of civilized warfare. This was Fairb’s laboratory. He would stand before men who had been farmers, lawyers, and lumberjacks just weeks before, and he would demonstrate the century take down. There is no such thing as a fair fight, his voice, clipped and precise would echo in the hush training hall.

A fair fight is a fight you are losing. Your goal is to finish the engagement before the enemy even knows it has begun. He taught them the chin jab, a strike with the heel of the hand, not to injure, but to break the neck. He taught them to use a simple garot and how to use the enemy’s own body weight against him to sever the corroted artery and ensure silence in under 3 seconds.

And then there was the knife, the Fairburn Sykes Commando knife. The instructors would hold it up. This, they would say, is not a tool. You do not open rations with it. You do not whittle wood with it. You do not even look at it unless you intend to use it. It is a human killer. The trainees were taught the body map, the vulnerable points.

First, the instructor would demonstrate on a strawfield dummy. The artery in the groin upward thrust. Second, the kidneys under the rib cage, a sideways thrust and twist. Heard the heart, a straight-on thrust, penetrating the sternum. Fourth, the throat, a slash, not a poke. And finally, and this was the most chilling, the silent kill through the back under the shoulder blade, puncturing the lung.

The man cannot scream. He cannot even breathe. He is dead. And the only sound is a faint wet gasp. This was the black art curriculum. It was so brutal, so effective, and so ungentlemanly that rumors of it, even within the Allied high command, were met with a kind of horrified disbelief. But killing one man was not enough.

The purpose of Campex was to kill infrastructure. After the trainees were hardened, after they had proven they had the stomach to kill in cold blood, they were moved from the black art studio to the demolition field. If Fairburn and Sykes were the headmasters of personal destruction, the SOE’s demolition experts were the masters of industrial scale chaos.

The quiet Ontario farmland was suddenly no longer quiet. The curriculum here was quite literally explosive. Trainees were introduced to a new miraculous and terrifying substance, plastic explosive. Nobel 808 or PE. The instructor, a man who had likely learned his trade in the Irish Republican Army, or the mines of Wales, would hold up a brick of the putty-like substance.

Gentlemen, or begin, this is your new best friend. It is pliable. You can mold it like clay. It is waterproof. You can drop it. You can even set it on fire. It will not detonate. He would light a corner. It would burn like a campfire log. But he would then take a tiny pencil-sized detonator, insert it, and attach a fuse.

With this, it is the hand of God. The fields of Ashawa became a surreal map of a war torn Europe. The instructors built a mock railway line in a gully. You do not blow up the train, the instructor would bark. You blow up the track at a curve with a pressure switch. You let the train’s own weight and speed do the work for you.

They were taught how to make limpit mines, magnetic bombs, and how to swim in the dead of night in the freezing water of Lake Ontario to attach them to the hull of a mock ship. They were taught the time pencil, a small copper tube, crush the end, and the acid inside would begin to eat through a thin wire. You had 30 minutes, no clockwork, no ticking, just a silent chemical fuse.

They were taught Özats explosives. How to make a powerful bomb from nothing. Flour, sugar, potassium nitrate. You can buy all of this at a local shop. You mix them. You have a bomb, a watch, a battery, a few wires. You have a timer. This was the forbidden knowledge. This was the training that Allied generals raised on cavalry charges and battlefield etiquette could not believe was being sanctioned.

They were not training soldiers. They were training a new hybrid terror. A man who had the silent killing skills of an assassin, the lockpicking and safe cracking skills of a master burglar, and the demolition knowledge of a rogue engineer. And this new deadly curriculum began to attract attention. In the spring of 1942, a very special visitor arrived at Campex.

He did not look like the other trainees. The other trainee were rough hune. They were Yugoslav partisans, Italian socialists, French Canadian lumberjacks, men chosen because their faces and languages could blend seamlessly into the occupied territories. This new man was different. He was tall. He was aristocratic.

He wore the immaculate uniform of a British Royal Navy commander. His name was Ian Fleming. Fleming was not there to train. He was a senior aid to the director of naval intelligence. He was there on behalf of intrepid William Stevenson to observe, to learn. He was essentially a student of the students. He stood at the edge of the woods, a cigarette holder clenched in his teeth, and he watched.

He watched Fairbear teach a man how to kill with a hat. He watched the demolition experts teach agents how to build a bomb inside a wine bottle. He saw the spycraft division, the lockpicking labs, the radio transmission rooms, the forgery departments where artists created perfect fake Gustapo documents. He was watching the birth of Q branch.

He was watching for the first time in his life the real world application of black propaganda, assassination, and high techch gadgetry. He was watching the theory of a license to kill being put into practice on a quiet Canadian farm. He took meticulous notes and from the mud, the blood and the high explosives of Camp X, the character of James Bond was being born.

The Allied high command was no longer skeptical. They were converted. The secret farm was working. It was taking in raw recruits. And in a brutal 6 week long crucible, forging them into the world’s most elite and deadly agents, men were graduating. They were being inserted back into Europe. And the reports were starting to come in.

A bridge in Yugoslavia critical to German supplies vanished. A high-ranking Gustapo chief in Prague assassinated a Yubot factory in Norway sabotaged. The impossible solution was proving to be an astounding success. But what the generals, what Ian Fleming, and what even most of the trainees didn’t know was that the school was a cover. It was an ingenious, perfectly executed distraction.

The true purpose of Camp X, its most vital forbidden secret, was not the men it was training to kill. It was something far more powerful. A secret hidden in plain sight. A secret that would not be fully understood for another 50 years. The most important secret at Campex was a broadcast antenna. The school for assassins was a master stroke of deception.

The explosions, the gunfire, the brutal visible training. It was all real, but it was also the perfect cover story. Because the most important forbidden art taught at Campex wasn’t how to kill a man. It was how to listen. The true purpose of this secret farm was hidden inside the original unassuming farmhouse. While trainees were being taught to garies, another quieter war was being waged in the building’s reinforced basement.

This was the nerve center, code named Hydra. It was one of the most sophisticated and most secret mall communications hubs of the entire war. The generals, the spies, even Ian Fleming had all focused on the human weapons being forged. They had missed the real secret. This farm wasn’t just a school.

It was the electronic ear of the western hemisphere. Intrepid. William Stevenson hadn’t chosen the Ashawa location just for its isolation. He had chosen it for its geography. The flat wet land bordering Lake Ontario was a perfect ground plane for radio signals. Its position in Canada made it the ideal midpoint to intercept highfrequency signals from Europe and relay them securely to Washington, London, and South America.

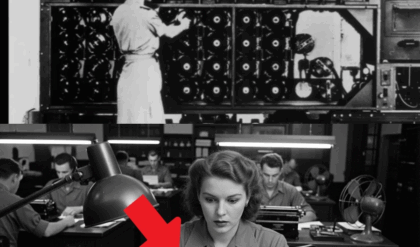

Hydro was the hub inside that farmhouse 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. A different kind of soldier worked. Many were young women from the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the Rens. They were linguists, mathematicians, and radio operators. They sat in windowless sustroofed rooms. Their headphones pressed tight. Their job was to pull signal from noise to listen to the ether.

And the ether was full. They intercepted everything. Coded messages from German Ubot in the Atlantic, diplomatic traffic from the Japanese embassy in Berlin, weather reports from spy ships, and most importantly, they intercepted the high-speed encrypted traffic of the German high commands Enigma machine. Hydra was a critical and often uncredited node in the Ultra program, the secret network centered at Bletchley Park in England.

The signals intercepted at Campex were cross-referenced, decoded, and analyzed. But Hydra did more than just listen. It talked. It was the primary and secure broadcast station for all British security coordination BT operations. When an SOE agent trained in the fields of Ashawa needed extraction from France, the coded action message was broadcast from Hydra.

When intrepid Stevenson needed to send a top secret decoded enigma message to President Roosevelt in Washington, often before Churchill had even seen it, that message passed through the operators at Hydra. This was the true forbidden art. Not the breaking of bodies, but the breaking of codes.

The assassins and saboturs were the fists of Camp X, the codereers at Hydra. They were the brain. The secret farm was in fact two operations in one, a school for killers wrapped around a signals intelligence station of global importance. And as the war entered its final brutal phase, the graduates of that school, the ghost of Ashawa, were finally unleashed.

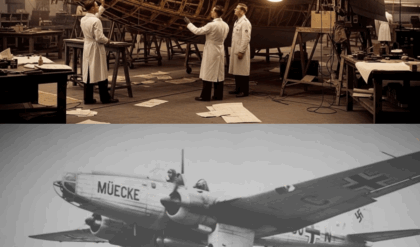

The payoff for the Allied high commands gamble was about to become legendary. Trained in the black arts and demolition, over 500 agents passed through the gates of Campex, they were given new identities, civilian clothes, and a cyanide pill. And then, one by one, they were dropped from the black bellies of Lysander aircraft into the moonlit fields of occupied Europe.

They did not fight in armies. They fought alone. A Norwegian graduate trained at Campex parachuted into his homeland and using the earthsat’s explosive techniques learned in Ontario destroyed a critical heavy water plant, crippling the Nazi atomic bomb program, a French Canadian team led by Schulier veterans linked up with the Maki. They didn’t just blow up a bridge.

They used their training to systematically sever every railway line and communication cable in northern France just hours before the D-Day landings, ensuring the German Panza divisions could not reach the beaches of Normandy. The impossible training had made the impossible invasion possible. But the greatest most enduring legacy of Campex was not what it did for the war.

It was what it did for the postwar. The most secret part of Stevenson’s plan was always the Americans. In 1941, America had no centralized intelligence agency. The FBI and the military intelligence branches were famously distrustful of each other. When America entered the war, President Roosevelt knew he had a spy gap.

He turned to his friend William Stevenson. Stevenson said, “Send me your men.” Roosevelt created a new organization, the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, and its leader, a hard charging lawyer named Wild Bill Donovan, made Campex the official training ground for his first generation of American spies. The future leaders of American intelligence were shipped in secret to this Canadian farm.

They were taught by Fairban how to kill. They were taught by the SOE how to blow things up. They were taught, in short, the ungentlemanly arts that America had never known. This secret farm became the blueprint, the prototype. The entire doctrine of American special operations and clandestine services was born in the mud and snow of Ashawa, Ontario.

When the war ended, the legacy of Campex was immediate. The OSS, having proven its worth, was disbanded and then almost immediately reformed under a new name, the Central Intelligence Agency, the CIA. The secret farm in Canada had in effect given birth to the most powerful intelligence agency the world would ever know.

And what became of Campex? The end of the school was as secret as its beginning. There was no parade. There were no monuments. In 1946, the mission was complete. The files were shredded. The records were burned. The instructors, Fairburn and Sykes, vanished back into the shadows. The Canadian government, true to its word, dismantled the entire facility.

The barracks, the firing ranges, the hydra station. It was all bulldozed, torn down, and plowed back into the earth. The land was sold. The secret farm was once again just a farm. It was a place designed to be forgotten. An operation so black that it was erased from its own history.

Today there is almost nothing left. A small quiet park, a single humble monument. But the forbidden knowledge taught there, it was never forgotten. The ungentlemanly warfare that the Allied generals couldn’t believe. It became the new standard. The ghosts of Ashawa are still with us. Their techniques, their methods, and their philosophy.

They now define the secret wars that are still being fought every single day in the shadows. History is full of these secret farms. Classified projects and hidden locations that change the world only to be erased. What other hidden locations or classified operations from the war do you think deserve to be brought into the light? Let us know your story in the comments below.

These are the operations that are so often lost to the official histories, the ones that don’t make it into the textbooks. Our mission here is to find them and to tell their impossible true stories. If you believe in keeping that history alive, subscribing is the best way to support the channel and ensure you don’t miss the next operation.