At 2:37 a.m. inside a Pratt and Whitney forge in East Hartford, Connecticut, the air itself shimmerred with heat. Sparks rained over steel boots, and the sound of hammers echoed like distant thunder. Men in leather aprons worked beside a furnace that burned white hot 2800° Fahrenheit, hotter than anything nature could withstand. Above the roar, someone shouted, “It’s splitting again.

” Another engineer, his face half hidden behind a visor, grabbed a steel rod glowing orange and watched it tear apart under its own weight. The metal had failed again. It always failed. In the early 1940s, as the Second World War devoured continents, British metallergists declared something that at the time sounded like fact.

No air cooled piston engine with more than 18 cylinders will ever hold together. The stresses are too great. The heat will destroy it from within. The most advanced aircraft in the world, the B17 Flying Fortress could carry four right cyclone engines producing one 200 horsepower each. It was a marvel, but it wasn’t enough.

The Pacific was too vast, the distances too great. To strike Tokyo, the United States needed something far stronger. An engine so powerful it could push a fully loaded bomber across 5,000 mi of ocean. The engineers at Pratt and Whitney heard the verdict from across the Atlantic and ignored it. They were told it couldn’t be forged, that no crankase could survive the torque, that the cylinders would overheat and seize.

But they were also told something else. Without a breakthrough, thousands of American crews would die in the Pacific before they ever reached Japan. So they began an experiment that bordered on madness. An attempt to create the largest, most complex air cooled engine in human history. Outside their foundaries, America was racing against time. Across the Pacific cities burned.

In Europe, bombers fell from the sky faster than factories could replace them. In Washington, generals were demanding a super engine capable of 3000 horsepower. Pratt and Whitney promised they could deliver 4,000. It was an impossible claim, but then again, impossible was a word that American industry had been erasing since 1941.

Inside the forge, molten aluminum poured like liquid sunlight into molds that would one day form the heart of a bomber. Every casting cracked, every cylinder head warped. Engineers blamed the heat. The metallurgists blamed the design. And yet every failure carried them a little closer to the truth.

They discovered that metal under enough stress behaved like a living thing. It expanded, twisted, screamed, and if treated right, it could learn to endure. By late 1942, the project was already a legend among factory workers. They called it the beast. Each test run ended the same way. A deafening roar, a rising vibration, then a violent bang that shook the concrete floors.

One engine exploded so violently it blew the test cell doors off their hinges. Reporters weren’t allowed anywhere near it. The engineers kept rebuilding, sleepless and stubborn, convinced that perfection was only one alloy away. Across the ocean, the British metallurgists watched and waited for the Americans to admit defeat. They never did. Instead, they melted.

More metal rewrote the textbooks and built a furnace hotter than anything in Europe. The heart they were trying to forge wasn’t just for a machine. It was for an entire generation of airmen who needed one last advantage to survive. By dawn, the forge quieted. The men stood around a new crank case cooling in the mold, unsure whether it would hold.

The supervisor, a man named Frederick Brackett, wiped soot from his face and said, “If it doesn’t break, we’re one step closer.” He turned to his crew, exhausted but unbroken, and added, “If it does, we forge it again.” They would hundreds more times.

And when that metal finally held, when the impossible heart began to beat at 3000 revolutions per minute, it would lift the heaviest bomber ever built into the sky and carry it halfway around the world. But for now, it was only heat hammering and faith. If you believe that determination can bend even steel, type the number seven in the comments. If you think they went too far, just leave a like.

Either way, what they built next would change the war forever. By the summer of 1942, the United States Army Air Forces faced a truth no one wanted to say out loud. The Flying Fortress, the B17, was magnificent, but it was not enough. Over the vast Pacific, its 1 200 horsepower engines gasped for air.

Fully loaded with bombs, fuel, and crew, it struggled to climb beyond 2000 0 ft. In Europe, that was survivable. In the Pacific, it was suicide. The Japanese homeland sat 5,000 mi from the nearest American base. No bomber on Earth could reach it and return. Inside the Pentagon, General Hap Arnold pounded the table in frustration.

If we can’t hit Tokyo, he said, “We can’t end this war.” The only solution was a machine that did not yet exist, a bomber twice the size of the B17 with a range beyond imagination. It would be called the B29 Superfortress. But to lift its 80,000 lb body into the thin air above the Pacific, it needed an engine unlike anything the world had ever seen.

The design request that landed on Pratt and Whitney’s desk was a challenge bordering on madness. An air cooled piston engine capable of delivering more than 3500 horsepower continuously at 3000 ft while weighing less than 3500 lb. Every known law of metallurgy said it couldn’t be done.

Each cylinder in such an engine would reach internal pressures of 1/200 lb per square in generating heat close to the melting point of aluminum. The stresses would tear the crank case apart in minutes. The British metallurgists at Rolls-Royce sent a cable to their American counterparts, warning that a 28 cylinder configuration would self-destruct from vibration harmonics.

The engineers at Pratt and Whitney read the warning and went back to work. They named the prototype R4, 360 Wasp Major, a name that hinted at both ambition and danger. The design stacked four rows of seven cylinders in a spiral pattern, each row offset to allow air flow around the fins. It looked less like an engine and more like a metallic hurricane.

The first full-scale test began in December 1942 inside a concrete test cell in East Hartford. The technicians bolted the massive block of metal to the floor connected fuel lines and stepped back as the starter motor winded. For 6 seconds, the R4360 roared to life, filling the room with blue flames. Then it detonated. The blast ripped the cowling apart and shattered two windows in the control room.

No one was hurt, but the message was clear. The Wasp Major was fighting itself. Each row of cylinders expanded at a slightly different rate, twisting the crankshaft by a fraction of an inch. Those fractions added up. The entire engine was vibrating at frequencies no one had ever measured before. It’s eating itself alive, one engineer wrote in his notebook.

Pratt and Whitney’s metallurgical department convened emergency meetings with the best minds in the country. They borrowed stress testing equipment from MIT chemical analysts from Yale and vibration specialists from Bell Labs. They filled notebooks with equations that stretched across pages like musical scores, calculations of torque, heat transfer, and thermal expansion. None of it seemed to work.

Every time they solved one failure mode, another appeared somewhere else. The Army Air Forces were running out of patience. A colonel from right field arrived unannounced one morning and demanded a status update. General Arnold wants to know when we can expect a working engine,” he said flatly. The lead engineer replied, “When we figure out how to stop physics.” The colonel didn’t laugh.

He reminded them that crews were dying in the Pacific, and that B29 production was already underway. The bombers were being built faster than their engines. By early 1943, desperation replaced optimism. The second prototype ran for 14 minutes before seizing. The third ran for 42 before a valve head broke off and shattered a piston. Each failure meant hundreds of hours of repair and redesign.

Mechanics worked under flood lights through the night, soaked in sweat and aviation fuel. The smell of scorched aluminium filled the air. One technician described the experience as listening to a giant hold its breath before it screams. Pratt and Whitney was not alone.

Across the country, rival companies were also chasing impossible power. Wright Aeronautical was developing the duplex cyclone, and Allison was testing a liquid cooled monster of its own. None were close to working. The British Merlin, the pride of Rolls-Royce, delivered barely half the required power and demanded constant maintenance.

The Americans wanted something soldiers could rely on, an engine that would run dirty, run hot, and keep running anyway. To make that possible, Pratt and Whitney engineers proposed a radical idea. If no existing alloy could survive the heat, they would invent one. They began experimenting with nickel chromium super alloys materials so exotic that they required entirely new furnaces.

They modified their forges to operate above 2 900° F, higher than anything previously used for aircraft parts. Each new batch of metal was tested until failure. Some samples exploded under the hammer. Others deformed into bizarre shapes that no machine could use. But slowly the data pointed towards something new.

A combination of nickel copper and aluminum that could hold its strength at 120° F without softening. Still, there was one more problem. Even if the materials held the complexity of a four row radial meant cooling would be almost impossible. Air couldn’t reach the inner cylinders and the engine risked melting from the inside out. Engineers sketched solutions on napkins ducted fins, forced air manifold secondary blowers.

Most were discarded by morning. Then a young designer proposed a fan mounted directly behind the propeller hub, forcing air into the center rows. It was crude but brilliant. The next test engine ran for an hour before failure, then two hours, then five. Each success was bought with risk.

During one test, a bearing seized, sending a connecting rod through the side of the crankcase. Shrapnel tore through the control booth. After that, technicians began wearing steel helmets. They joked that if the R4,360 ever flew, it would take off just to escape the test cell. By mid 1943, the pressure was unbearable.

The Army had ordered 300 B29s and threatened to cancel the contract if the engine wasn’t ready. In the cafeteria, someone painted a sign above the coffee earn. Remember, men are dying while you drink this. The workers understood. Some hadn’t been home in months. Others slept in their offices, waking at the sound of test alarms.

One machinist told a reporter, “Years later, “We stopped thinking about engines. We started thinking about survival.” The crisis reached its peak in July. The fifth prototype redesated Model C was scheduled for its first endurance run. As the test cell filled with mechanics, Frederick Brackett stood at the control board, his hands trembling, he nodded to the operator.

The starter winded, the engine coughed, and then for the first time, it didn’t explode. It settled into a deep, thunderous rhythm. 2400 revolutions per minute, smooth, even alive. After 30 minutes, someone shouted, “It’s holding.” The room erupted in cheers. They had done it, or so they thought. At 47 minutes, a cylinder cracked. Oil pressure dropped to zero.

The Wasp Major seized its giant propeller, spinning to a halt. Silence filled the cell. Bracket exhaled and said quietly, “We’re getting closer.” Then he turned to his team, “Tear it apart. Find out why.” They would, and each time they did, they came back stronger. If you think they should have given up after the fifth explosion hit, like, “If you believe that failure is only the step before discovery, type the number seven in the comments.

” What they found next would turn one man’s experiment into the beating heart of America’s flying fortress. By the winter of 1943, the Pratt and Whitney plant in East Hartford no longer slept. The windows glowed orange through the night like a city under siege. Men and women drifted in shifts between the machine shops and the test cells, their faces smudged with graphite and fatigue.

The cafeteria never closed. The war had turned the factory into a living organism, breathing, sweating, deafened by the heartbeat of engines that refused to die quietly. At its center was Frederick Brackett, 53 years old, with thinning gray hair and the calm voice of a teacher. He had been a metallurgist before the word meant much to anyone.

His office was a single desk buried under sketches, chemical charts, and coffee rings. He believed machines had souls born in fire, hardened by stress, and sustained by human stubbornness. The R4,360 was his most defiant student. Every time it shattered, he started again. When younger engineers cursed the design, Brackett would whisper, “The metal is telling us something. We just need to learn its language.

” He lived inside the factory now, sleeping on a cot behind the forge. His wife mailed him letters that piled unopened on his desk. He’d read them weeks later under the dim yellow light of a drafting lamp. “You sound tired,” she wrote once. “Remember that engines can wait. You can’t.

” He smiled at that, folded the letter, and slipped it into his coat pocket before returning to the floor. “Engines couldn’t wait. Not when the war was burning faster than they could build.” One evening in January 1944, a young mechanic named Samuel Ortiz approached him. Ortiz was 22 from El Paso, a machinist’s apprentice before the war.

He had joined the factory after his older brother was killed flying a B-24 over the Pacific. He asked Bracket, “Sir, if this engine works, does that mean fewer boys die out there?” Bracket hesitated. If it works, he said softly. It means their chances are better. But engines don’t end wars, Sam. People do. Ortiz nodded and went back to polishing valve covers that gleamed like mirrors.

These people weren’t soldiers, but they lived with the same sense of duty. The women in the assembly lines the welders with burns on their arms. The test cell crews who risked their lives each time they hit the starter switch. Each understood that the war’s front lines began right there in the glow of molten metal.

When a prototype exploded in February and shrapnel tore through the control booth, one technician, Robert Kaine, lost two fingers, shielding a coworker. He refused to leave the hospital until Brackett signed his cast with a pencil. It held longer this time. Every test was theater and terror.

The engineers watched through thick glass hearts pounding as the propeller blurred into a disc of light. They could tell by sound whether the run would survive. A healthy engine had a rhythm, a low, steady growl. When it went wrong, the pitch climbed like panic made audible. Then came the bang, and everything stopped.

The smell of burnt oil filled the air, followed by silence and the click of cooling metal. Outside the test cells, life compressed into hours. Workers ate standing up. The plant’s loudspeakers blared news from Europe and the Pacific Anzioan Laty Gulf while they hammered crank cases and balanced crankshafts. They didn’t need to be told what was at stake.

Some had sons or husbands already flying missions powered by earlier versions of Pratt and Whitney engines. Every vibration they corrected could mean one more plane returning home. Brackett rarely spoke about the cost, but it was written in his posture, in the way he lingered beside a running test cell as if listening for ghosts.

One night an assistant found him alone staring at a cracked cylinder head. It’s a miracle, you know, Bracket said quietly. Metal shouldn’t survive this. None of it should. And yet somehow it does. Maybe we’re teaching ourselves more than the machines. By spring, they were close. The latest prototype, the Model D, had run for 14 hours without failure.

The team celebrated with stale coffee and laughter that felt foreign after months of exhaustion. Someone brought a photograph and played Glenn Miller through the plant loudspeakers. For a brief hour, the war felt far away. Then the next morning, one of the cooling fins fractured. The test was over. No one spoke for a long time.

The following week, a letter arrived from the front. It was from a B-29 crew chief stationed in Guam. We hear you’re building something big. It read, “Whatever it is, hurry. These engines burn oil faster than we can fill it.” Bracket pinned the letter to the bulletin board where everyone could see it.

The next day, no one complained about overtime. The plant grew quieter after midnight, but it never stopped. In the foundry, sparks fell like rain. In the assembly bays, the rhythmic click of rivet guns echoed off steel walls. And in a small corner office, Bracket made his final notes for a new alloy, one that would stretch without cracking, absorb heat, without deforming, and live longer than any engine before it.

He named it 75 Eniku, but the men just called it the survivor. When the new parts arrived from the forge, Brackett refused to leave the test cell. He wanted to see the run himself. Ortiz stood beside him, hands trembling. “You think it’ll hold?” he asked. Brackett smiled faintly. “I think it has to.” At 11:8 p.m., the starter engaged.

The R4,360 roared to life, filling the cell with sound so deep rattled the windows two buildings away. Flames licked from the exhaust stacks, painting the walls orange. The vibration gauges danced but stayed within limits. 10 minutes passed, then 30, then 2 hours. The gauges held steady. For the first time in a year, the engine refused to die.

When they finally shut it down, the silence felt unreal. No explosion, no smoke, no failure, just a faint tick of cooling metal and the slow smiles of men who had forgotten how to celebrate. Brackett placed a hand on the warm crank case, feeling the pulse beneath his palm. Now he whispered, “We teach it to fly.” That night he wrote a single line in his log book, Endurance Test.

Successful. The metal has learned. If you believe that machines carry the fingerprints of the people who build them, type the number seven in the comments. If you think no amount of human will can change the laws of physics hit like the truth as always was waiting inside the next test.

When the engineers finally tore down the R4,360 after its first successful run, what they saw inside was both terrifying and beautiful. The pistons had endured temperatures close to 1/200° F. Yet the new alloy had not cracked. The bearings showed uniform wear. The crank case, that immense forged heart of aluminum and nickel, held its shape with surgical precision.

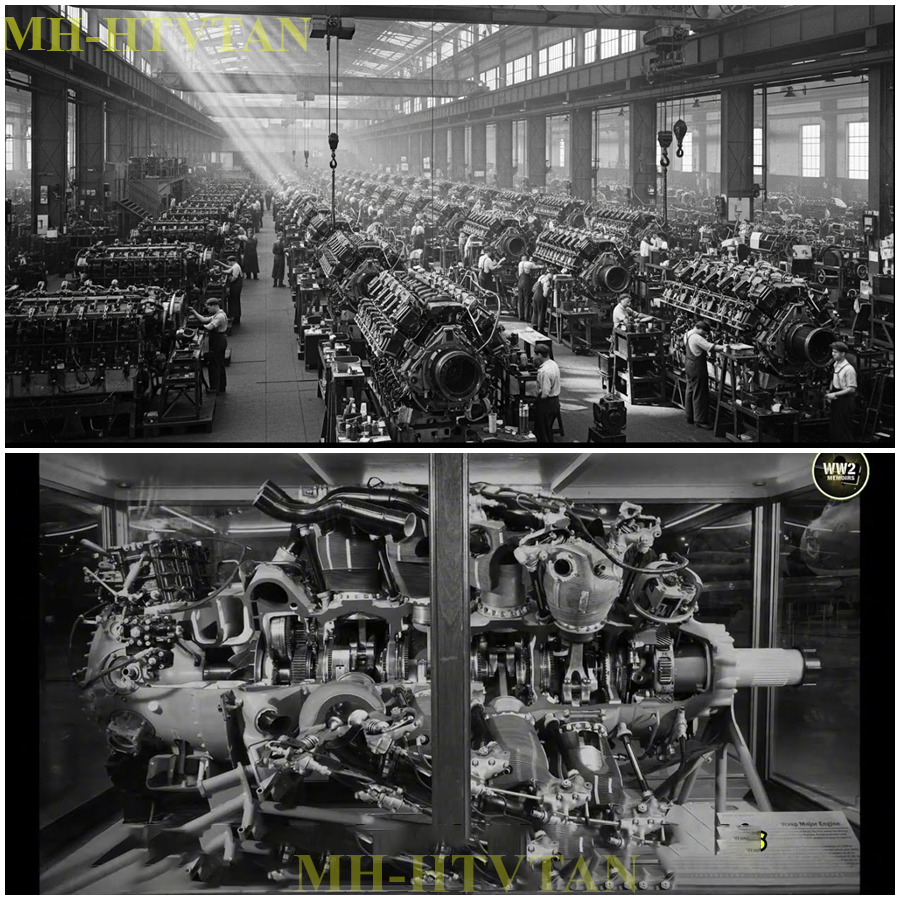

It was proof that the impossible machine could live. But what came next would transform it from an experiment into a weapon of war. The Wasp Major wasn’t simply an engine. It was a cathedral of moving metal. 28 cylinders arranged in four spiraled rows around a central crankshaft. Each one firing in a pattern that sounded more like thunder than combustion.

At full throttle, those cylinders inhaled 2,000 cubic feet of air every minute and consumed fuel faster than a truck could pump it. A web of oil lines fed pressurized lubricant to 140 critical points. 16 magnetos controlled ignition for 56 spark plugs.

Even the smallest components from piston rings to connecting rods had to be redesigned for stresses no aircraft engine had ever endured. Cooling remained the great unsolved mystery. The outer cylinders received plenty of air flow, but the inner rows baked in trapped heat. Engineers compared temperature readings. Outer row 375° F. in a row 575° F. The difference was catastrophic.

At those temperatures, the engine would seize within hours. The solution came from an unlikely source, a young draftsman named Harold Wentworth, who had studied wind tunnels before the war. He proposed a front-mounted impeller fan driven by a gear train directly off the crankshaft. It would push 2000 cubic feet of air per second through ducts that snaked around each row of cylinders.

The modification increased drag, but the payoff was survival. When they tested the new cooling fan in July 1944, the results shocked even the veterans. For the first time, all cylinder temperatures remained within 15° of each other. The engine ran for 20 hours continuously without mechanical failure.

The vibration charts flattened into perfect lines. “It’s singing,” one technician said, watching the oscill trace a steady rhythm across the paper. The next breakthrough came in supercharging the art of feeding the engine more air than nature provided. Previous designs used single stage mechanical blowers. The R4,360 needed something far greater.

Pratt and Whitney built a massive three-stage turbo supercharger combining exhaust driven turbines with gardriven compressors. It was a system so complex that it required its own oil cooling and pressure regulation. When combined with the new intercoolers, the Wasp Major could maintain full sea level power above 3000 ft. At that altitude, most engines gasped for breath. The Wasp Major exhaled fire.

At 3500 horsepower, the propeller became the next limitation. Conventional blades simply couldn’t handle the torque. Hamilton Standard Engineers developed a 13 ft four-blade propeller with paddle tips each, weighing over 100 lb. At full speed, the blade tips approached the speed of sound. Ground crews wore ear protection even at idle.

Pilots later described takeoff as sitting inside a tornado made of metal. Production began almost immediately. The East Hartford plant expanded by 40%. Entire new foundaries were built to forge crankshafts that weighed 600 lb each. The process demanded presses capable of 1200 tons of force so massive that their foundations had to be poured 30 ft deep to absorb the shock.

The forged planks glowed like miniature suns as workers guided them with tongs the size of tree trunks. In the machining shops, lathes carved each piece down to tolerances measured in 10,000 of an inch. Every finished crankshaft passed X-ray inspection for hidden cracks, a procedure that used equipment originally developed for atomic research.

Assembly lines moved with a rhythm closer to orchestra than factory. Blocks advanced station by station, gaining pistons, push rods, magnetos, superchargers. Women wearing red bandanas and oil stained gloves tightened bolts with torque wrenches as inspectors checked serial numbers. A single completed engine contained more than 7,000 individual parts.

Fully dressed, the Wasp Major weighed 3400 lb, nearly 2 tons of precision engineering. By late 1944, Pratt and Whitney could produce 10 engines a day. Each was mounted on a test stand for a 4-hour acceptance run. The roar could be heard for miles. Local farmers complained that it frightened their livestock. The engineers smiled. The sound was music to them.

Meanwhile, Boeing’s B29 Superfortress was waiting. The bomber that demanded this miracle of metallurgy was nearly complete. Its wings spanning 141 ft were designed around the Wasp Major’s dimensions. Without those engines, the entire program would collapse. The Army had already invested $2 billion more than the cost of the Manhattan project.

Failure was not an option. On the morning of September 21st, 1944 at Boeing Field in Seattle, the first B-29 fitted with four R4, 360s prepared for its maiden flight. The crew chief, Lieutenant Frank Reynolds, walked beneath the wings, touching each NL as if reassuring himself that they were real.

Each engine gleamed under the sun, its cooling fins catching the light like armor. Inside the cockpit, pilot Eddie Allen flipped the ignition switches one by one. The first engine turned over with a deep cough, then stabilized into a steady thunder. The second joined, then the third, then the fourth. The noise was indescribable, a symphony of controlled violence. Allan released the brakes.

The bomber rolled forward slowly at first, then faster, lifting its immense weight off the runway after just two 500 ft. Ground crews cheered as it climbed into the sky. The impossible engine was flying. At 100 feet, Reynolds checked the gauges oil pressure steady. Cylinder head temperature within range. Fuel flow nominal. The radio crackled. She flies smooth. Allan said feels lighter than she should.

They circled for 30 minutes before returning to land. When the propellers wound down, the airfield fell silent except for the ticking of cooling metal. No failures, no smoke, no fire, just four living hearts beating beneath a steel wing. The technical reports that followed were almost reverent.

Power output stable at 3 500 horsepower continuous one read, “Vibration levels negligible. Endurance projected beyond 400 hours. In an era when most combat engines required overhauls after 100 hours, it was a miracle.” But what truly astonished observers was scale. The Wasp Major wasn’t a boutique machine built by artisans. It was a product of mass production.

Pratt and Whitney Ford and General Motors collaborated to build parts across the country. Forges in Cleveland produced crank cases. Plants in Kansas City built cooling fans. Final assembly line stretched across five states. By 1945, America was producing enough Wasp majors to power an entire fleet every month. Behind each engine was a human story.

A worker in Ohio machining his thousandth piston. A young woman in Connecticut stamping inspection numbers on spark plugs. None of them would ever fly a B29, but each left fingerprints on the machine that carried the war’s final missions. In its final configuration, the R4,360 generated 4300 horsepower, twice the output of the British Merlin and three times that of Germany’s best radial engines.

It propelled bombers and transports heavier than any before them. Its roar echoed across oceans, a sound that signaled both victory and the beginning of an age when machines outgrew the men who built them. The engineers gathered for one last test in early 1945, a 200-hour endurance run. The Wasp Major ran for eight consecutive days at full power without a single mechanical failure.

When they shut it down, the technician stood in silence. Frederick Brackett placed his hand on the warm casing and whispered, “It didn’t break.” That night, he wrote a new entry in his log book, Engine Complete. Production authorized. This heart is ready for war.

If you believe that human determination can turn molten metal into history, type the number seven in the comments. If you think no engine, no matter how strong, can carry the weight of an entire war hitlike. Either way, the world was about to discover what happens when the impossible learns to fly. At dawn on March 9th, 1945, 40 mi off the coast of Japan, 400 B29 Superfortresses formed a shimmering line of silver against the horizon.

Inside each of those bombers, four R4,360 Wasp major engines pulsed like beating hearts, their overlapping sound merging into a single mechanical thunder that rolled across the sea. Pilots described it as the sound of the earth moving. Below them, Tokyo slept under a thin veil of mist, unaware that the largest air raid in human history was minutes away.

For years, Japan had watched American bombers attack from distant islands, always at the edge of possibility. But the Wasp Major changed that. With four of those engines each producing more than 3500 horsepower, the B-29 could climb higher, fly farther, and carry heavier loads than any bomber before it.

Its operational ceiling exceeded 3000 ft, far above the reach of most Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft guns. Its range over 500 mi meant no corner of the Japanese Empire was safe. The Pacific, once a barrier, had become a runway. The first mission from Tinian Island to Tokyo covered more than 500 miles each way.

The pilot sat in pressurized cabins, watching the red glow of exhaust flames dance against the black ocean below. Lieutenant Jack Simmons, flight engineer aboard Lucky 7, wrote in his diary, “I can feel the engines through the floor. It’s not a vibration anymore. It’s a heartbeat. As long as it beats, we live.” That night, 279 of the bombers reached Tokyo. They dropped 1665 tons of incendiary bombs.

The resulting firestorm incinerated 16 square miles of the city. Over 100 people died and another million were left homeless. It was destruction on a scale no one had imagined made possible by the engines that refused to fail. For the crew’s survival depended entirely on those engines. The missions lasted 12 to 15 hours. If one failed, the bomber might limp home.

If two failed, it was finished. But the Wasp Major rarely quit. Unlike earlier engines that choked in thin air or overheated on climb, the new design maintained power even in the tropics. Oil temperatures remained stable. Cylinder pressures held constant. Pilots said the engines sounded like they wanted to keep flying even after we landed.

Each flight began with a ritual. Ground crews lined up beneath the wings before takeoff, holding oily rags and wrenches. They listened as the flight engineer hit the magneto switches one by one, left to right. Each engine came alive with a roar and a flash of smoke. The crews cheered when all four caught and settled into that steady rolling thunder. They knew the sound meant their friends might come back.

The Wasp Major gave the B29 a level of performance that transformed air strategy. It could cruise at 350 mph, climb to 3100 ft, and carry 10 tons of bombs across oceans. Its reliability allowed for mass raids, hundreds of planes taking off within minutes of each other, each engine synchronized to the rhythm of the next.

When those bombers filled the sky, even Japanese aces like Saburo Sakai with 64 kills to his name admitted defeat. “We could not reach them,” he said. After the war, they flew higher than our fighters, faster than our bullets. By June 1945, the B29’s range extended far beyond Tokyo.

Osaka, Nagoya, Kobe, city after city, burned under waves of incendiaries. Engineers back in Connecticut followed every report. They noted the total flight hours before each engine overhaul. 412 487 523. The Wasp Major wasn’t just surviving. It was thriving. One after another, the test logs recorded an impossible statistic zeroin-flight mechanical failures during entire squadron missions.

The engines changed the war’s arithmetic. Instead of launching small limited raids, the Americans could now sustain aroundthe-clock bombing. The logistical chain stretched from Kansas to the Mariana’s engines forged in Hartford shipped by rail to the coast loaded on Liberty ships installed on new bombers at Guam.

Every success on the front lines echoed back to those furnaces where the metal had first been born. On August 6th, 1945, a B29 named Enola Gay lifted off from Tinian carrying a single bomb cenamed Little Boy. The 4R R4,360s pushed the aircraft down the runway and into the humid air before dawn. Each engine turned two 500 revolutions per minute, their combined power equal to 1400 horses, straining against gravity.

At 8:15 a.m., the bomb fell over Hiroshima. 3 days later, another B29 Boxcar dropped a second bomb on Nagasaki. The war was effectively over. Historians still debate whether the atomic bombs or the relentless fire raids forced Japan’s surrender. But for the men who flew those missions, the Wasp Major was the one constant.

It was the unbreakable chain between science and survival, between industry and destiny. After the surrender, when pilots taxied their bombers home one final time, they often reached out to pat the throttle levers as if thanking a living thing. One ground chief, Master Sergeant Howard Briggs, remembered watching a returning B29 roll to a stop after its last mission.

We stood there as the prop slowed down, he said. You could feel the silence spread. For months, that sound had been our life. The roar, the heat, the vibration. When it stopped, it felt like the war itself had stopped breathing. The R4,360 had done what its creators promised. It carried men and bombs across the largest ocean on Earth, flew through storms, endured heat salt and combat damage.

It turned the Pacific into a corridor of steel wings, and when the last mission ended, it left behind a lesson that outlived the war. That industrial genius could achieve what courage alone could not. If you believe that technology can be both a savior and a curse, type the number seven in the comments.

If you think wars are won not by machines, but by the people who build and fly them, hit like. Either way, what came after this victory would prove that even the greatest engines have limits, and that every heartbeat, mechanical or human, must one day fall silent. When the war ended in August 1945, silence returned to East Hartford for the first time in four years.

The forges cooled, the night shifts ended, and the sound that had once filled every street, the deep rhythmic thunder of the Wasp Major, faded into memory. The men and women who had built it walked out of the gates carrying lunch pales instead of blueprints. The war was over, but for many of them, life without that noise felt strangely empty. Frederick Brackett stayed behind long after the last bomber returned from the Pacific.

His desk was still covered with sketches, test logs, and fragments of metal he refused to throw away. One of them, a cracked piston crown, sat on his window sill. He’d kept it as a reminder that even the strongest material breaks eventually. Engines die, too. He once told a visiting reporter, “You just hope they die after you don’t need them anymore.” The R4,360 had been designed for war, but peace brought new demands.

The US Air Force reclassified it as a strategic engine for post-war aviation. It powered the massive B-50 bombers that replaced the B-29s and later the enormous C97 Stratoer transports that carried cargo across continents. Each aircraft bore the same unmistakable sound, a slow rolling growl that could be heard 10 miles away.

Airline passengers in the early 1950s would sit by the windows of Boeing Strata Cruisers watching the giant propellers blur against the sky, unaware that the engines beneath them had been born in the fires of war. The numbers were staggering. Between 1944 and 1955, more than 1800 W wasp majors were built. They consumed enough aluminum to build a city enough copper wire to circle the earth twice.

Yet by the end of that decade, the world had already moved on. Jet engines, once fragile experiments, were now proving reliable and faster. A pair of General Electric J47 turbo jets could produce more thrust than four of Brackett’s masterpieces combined. The sound of the future wasn’t a roar anymore.

It was a whistle. At first, the engineers resisted. They argued that the piston engine was a proven design that it could be improved. Refined, pushed even further. Pratt and Whitney built the R4,3663 variant for the Convair B36 Peacemaker, each delivering 3800 horsepower, augmented by four jet engines under its wings.

For a brief moment, the old and the new shared the sky propellers and jets side by side. Pilots said it felt like two eras shaking hands mid-flight. But the handshake didn’t last long. By 1956, pure jet propulsion had taken over. Factories that once forged crankshafts now built turbine blades. The great hammers went quiet. The last Wasp major rolled off the assembly line in 1955. Technicians stood around it for a photograph.

12 men in oil stained uniforms beside a shining engine that looked more like sculpture than machinery. On its cowling, someone had written in chalk, “She never quit.” Brackett retired a year later. On his final day, he carried that cracked piston home and placed it on a wooden shelf in his garage. He still received letters from former co-workers, some from pilots who had flown behind his engines. One read, “Your medal brought us home.

” Another said, “We trusted the sound.” He never replied, “But he kept everyone.” In the years that followed the Wasp Major found new life in the civilian world, Crop Dusters firefighting aircraft experimental transports, but those were echoes of its former glory. The age of the piston giant was over. Museums began collecting the engines, polishing them for display.

Children would stand beside them in awe, unable to imagine that something so large had once fit inside an airplane wing. Guides would point to the brass placard Pratt and Whitney R4,360 Wasp Major 4300 horsepower. The kids would nod, not understanding that behind those numbers were knights of failure, danger, and brilliance. For Bracket, the end of the Piston era wasn’t a tragedy. It was evolution.

He once told a young journalist, “Every machine has its sunset. The best ones leave a glow long after the light fades.” When he died in 1962, the facto’s new generation of engineers men working on jet turbines lowered the flag at half staff. They might never build something as loud, but they would never forget what that sound meant.

In one of the last surviving photos of Brackets Forge, a worker is seen closing the furnace door. Behind him, the floor glows faintly red, the heat still alive under the surface. The caption reads, “East Hartford, 1946, end of shift.” You can almost hear the echo of engines in the distance fading but never gone.

If you believe that every ending is just the beginning of another kind of invention, type the number seven in the comments. If you think greatness should be measured not by how long it lasts but by what it inspires next hit like. Either way, the Wasp Major had earned its rest and left behind a silence loud enough to remember.

Today, only a handful of R4, 360 Wasp Major engines still breathe. They sit behind museum ropes in silent halls across America, Dayton, Seattle, Pensacola immense and still polished to a mirror shine. Once they filled the sky with thunder. Now they rest under soft lights, each one a monument to the power of human persistence.

On some weekends, mechanics gather to start them just to keep them alive. Visitors cover their ears as the ignition sparks, the giant propeller blurs, and the air shutters. The first sound isn’t a roar, but a pulse. Deep, rhythmic, ancient. For a few minutes, time itself seems to step backward to an age when noise meant survival and fire meant flight.

When the engineers of the jet age look back at the Wasp Major, they see not an obsolete relic, but a blueprint of everything that came after the material science born inside its furnaces, nickel chromium alloys, high temperature bearings, precision forging became the foundation for turbine blades, rocket engines, and even nuclear reactors.

Its cooling systems inspired designs still used in modern air cooled turbines. Its supercharger principles evolved into jet compressors. The Wasp Major didn’t vanish. It transformed piece by piece into the future. Yet, its legacy isn’t only mechanical. It’s human. Every bolt torqued, every piston polished, every shift worked through exhaustion told a larger story about a generation that refused to accept impossible.

They were factory workers, machinists, engineers, and dreamers. Most never saw the planes they powered never met the men their engines saved. But they knew in the roar of every test cell that their work mattered. In the quiet years that followed, many said they missed that sound more than anything. When it stopped, one welder remembered it felt like the country stopped breathing for a while.

The Wasp Major was more than a machine. It was the last heartbeat of an industrial age where human hands and molten metal built miracles side by side. It belonged to a time when blueprints were drawn with pencils and courage when engineers risk their lives to test what textbooks said couldn’t exist.

Its very existence proved that progress is never gentle. It’s hammered, forged, and tempered by failure until it learns to survive. Decades later, when one of those preserved engines is started for demonstration, people gather around with phones and cameras, waiting for the first cough of ignition. The engine hesitates, then catches. The old propeller spins faster.

The exhaust stacks flash with orange flame and suddenly the floor vibrates underfoot. The sound fills the hanger, rolls up through the roof and out into the sky. Some of the older visitors close their eyes. They remember father’s uncles or grandfathers who built or flew behind that sound.

The younger ones only stare half terrified, half mesmerized by a noise that feels alive. In that moment, the Wasp Major lives again, not as a weapon, but as a reminder of what people can do when fear and time close in. It is proof that genius can exist on a factory floor, that courage can live in a forge, and that history isn’t written only by those who fight wars, but also by those who build the engines that make them possible.

Frederick Brackett’s name is engraved on a small brass plaque at the New England Air Museum. It reads Chief Metallurgist Pratt and Whitney, R4, 360 Wasp Major, 1942, 1945. That’s all. No medals, no speeches, no fanfare. Just a few words marking the man who taught metal to endure. Beneath that plaque, the engine still stands silent, immense, and unbroken.

When historians speak of America’s triumph in World War II, they talk about strategy, industry, and bravery. But behind all of it were hands like brackets, callous, burned, trembling, and steady. The Wasp Major was their masterpiece, the mechanical soul of a nation that built strength out of doubt and turned sweat into flight. If you believe that history is not just about battles, but about builders, type the number seven in the comments.

If you think progress should always honor the hands that forged it, hit like. And if you want to keep stories like this alive, subscribe because these engines may have stopped running, but their echo still shapes the world we fly through