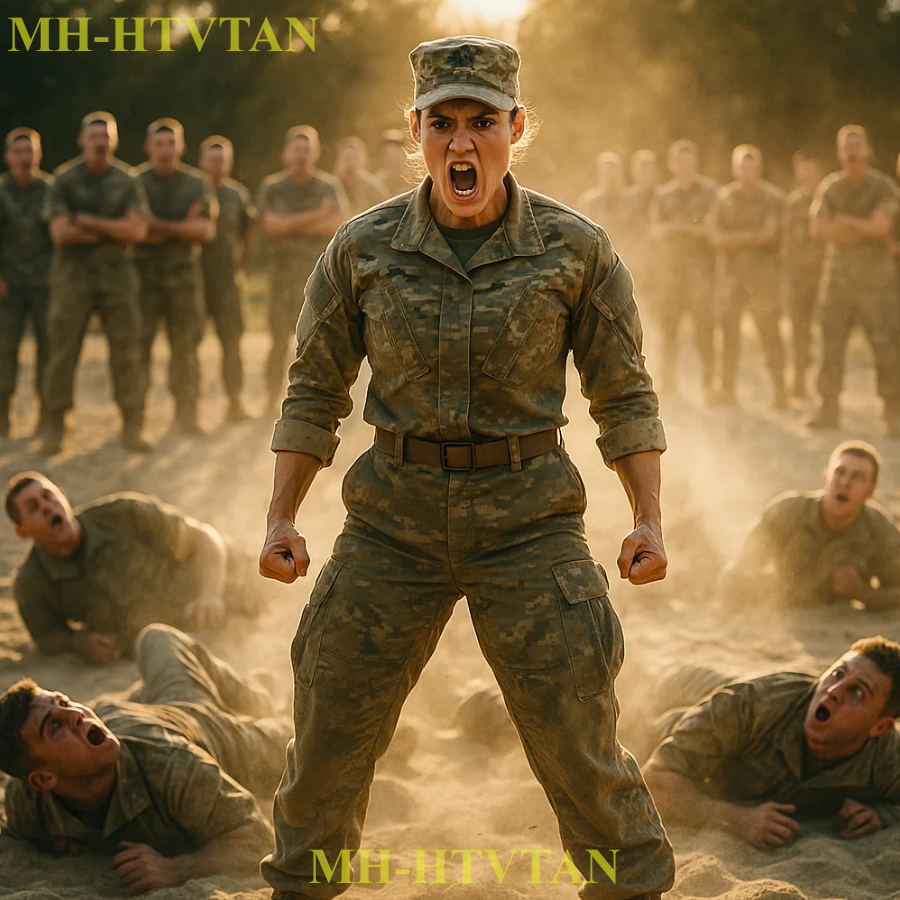

The lead cadet whispered to his buddies as Staff Sergeant Vera Castellane entered Fort Benning’s combives pit. The three males, each outweighing her by 60 lb, had no idea they were about to face someone who’d learned bone-breaking techniques from her grandfather before she could write her own name.

The modern army combatives training facility at Fort Benning stretched out under George’s August sun. The sand pit already radiating heat at 0600 hours. Staff Sergeant Vera Castellion, 29 years old, had arrived the previous evening as the new combatives instructor for the infantry basic officer leader course, working under Master Sergeant Rodriguez, who’ specifically requested her after reviewing her qualifications.

5’7 and 140 lbs of functional muscle, she moved with the controlled efficiency of someone who understood violence as both art and science.

Her left shoulder bore the ranger tab she’d earned 2 years prior at age 27, completing all 61 days without recycling, one of fewer than 50 women to achieve that distinction since the course opened to females. The morning light caught the scar tissue on her knuckles, each mark a lesson learned in places where second chances didn’t exist.

She’d been brought in specifically to address a problem. The command had identified two many officers were graduating eyeball sea with theoretical combat knowledge but no practical understanding of close quarters violence. Vera’s education in violence began in the Louisiana bayou outside Fort Poke where her grandfather Master Sergeant Jerome Castellane had settled after retiring from the 173rd Airborne Brigade in 1971.

He served three tours in Vietnam as one of the army’s first black combatives instructors, developing techniques that merged military close combat with the street fighting he’d learned surviving Jim Crow era New Orleans. By age six, Vera could execute a blood choke that would render an adult unconscious in 8 seconds.

Her grandfather believed real safety came from understanding danger completely. He’d make her practice on him, teaching her to feel the exact moment when pressure became lethal, when a joint lock shifted from control to destruction. Her father, Captain Marcus Castellane, had died in Iraq when she was 12, not from enemy fire, but from a preventable training accident during combatives drill when his partner panicked and crushed his trachea.

The official report blamed inadequate instruction and poor supervision, words that burned into Vera’s memory like a brand. She joined at 18, starting as an enlisted soldier, earning her black belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu while stationed at Fort Campbell, competing in underground military fight circuits where rank meant nothing and only skill mattered.

Her grandfather had lived long enough to pin on her ranger tab, dying two months later with her standing at his bedside. his final words about how she’d carry forward what he’d started. During Ranger School’s mountain phase, she’d survived an ambush exercise by taking down three opposing students in 23 seconds, using techniques that weren’t in any manual, but came from decades of family knowledge.

The three officer candidates had planned their ambush for a week. Ever since word spread that some female sergeant would be teaching warriors how to fight, officer candidate Brandon Teller, 6’3 and 220 lb of former University of Alabama linebacker had organized the confrontation with candidates Morrison and Hayes, both over 6 ft, and built from years of collegiate athletics.

They’d convinced the duty instructor, a young corporal who didn’t want to seem weak in front of officer candidates, to let them use the pit for early morning training, claiming they wanted extra practice before the new instructor arrived. Taz Vera approached. Teller stepped forward with the confidence of someone who’d never truly lost at anything physical, announcing loud enough for the gathering crowd of 40 plus candidates that maybe she should start with something more appropriate for her skill level, like teaching supply clerks how to count MREs.

Morrison added that his 14-year-old sister had earned a black belt too at her strip mall dojo, wondering if that’s where the army was recruiting instructors now. Hayes, slightly smaller at 6’1 but trained in high school wrestling, mentioned how everyone knew the Ranger school standards had been compromised to push females through for political points.

The crowd had their phones out despite regulations against recording in training areas. Expecting to capture the moment when reality met diversity quotas, Teller proposed what he called a friendly demonstration. three candidates against one instructor, light contact only, just to help establish proper respect for the training hierarchy.

He emphasized the word hierarchy like it was a weapon, his smile showing he expected her to invoke rank, call for backup, or find an administrative escape from the challenge. The morning air carried the smell of pine resin and sweat, triggering a memory from when Vera was 16, standing in her grandfather’s backyard as he taught her the principle that would define her approach to combat.

Violence should be swift, decisive, and educational. These boys reminded her of every undertrained soldier who’d ever confused size with capability. Every officer who’d graduated thinking combatives was just another PT requirement rather than a survival skill that could mean the difference between a folded flag and a homecoming.

Her father’s death certificate sat in a frame on her desk, a permanent reminder that poor training killed more soldiers than enemy action ever would. She noticed what the candidates missed in their performed masculinity. Teller’s right knee showed surgical scars from an ACL repair that would limit his lateral movement.

Morrison kept dropping his left shoulder in an unconscious telegraph. Hayes had the overconfidence of someone who’d only fought within wrestling’s rules and referee protections. The crowd expected her to retreat into regulations to use her rank as a shield to demonstrate that female soldiers needed institutional protection to function.

Instead, she removed her patrol cap with deliberate precision, folding it exactly as her grandfather had taught her. Three perfect creases that turned cloth into commitment. She stepped into the pit’s center, her body language shifting from administrative to predatory in a way that made several observers unconsciously step backward, their primitive brains recognizing a threat their conscious minds couldn’t yet process.

Teller entered first with a football player’s charge, the kind that worked when you had pads and teammates, but exposed everything in single combat. Vera read his approach like a children’s book, shoulders telegraphing, weight too far forward, chin exposed in his eagerness to prove a point. She executed her grandfather’s ghost step, a lateral movement that put her at a 45° angle to his rush, her hand guiding his momentum past while her foot swept his planted leg.

But instead of following him down, she let him stumble forward into the pit wall, saving the real lesson for when all three engaged. Morrison and Hayes separated to flank, thinking they were being tactical, but they’d just given her what every smaller fighter needed, space to create angles and momentum. Hayes shot for a wrestling takedown from her right, his form textbook perfect for a mat, but wrong for sand that shifted under pressure.

She sprawled hard, driving his face into the grit, while her knee found the nerve cluster at his lower back. Not the sciatic nerve, but the lumbar plexus. A strike that would temporarily weaken his legs without permanent damage. Morrison threw a haymaker from her left, all power and no precision, the kind of punch that looked impressive in movies, but took too long to land in reality.

She slipped inside his ark, her elbow driving into his solar plexus with the focused energy her grandfather called a lightning strike, maximum effect from minimal movement. The crowd’s phones captured her flowing between attackers like water finding cracks in stone, using their commitment against them in ways that seemed to violate physics, but simply applied it perfectly.

Teller recovered from his stumble and charged again, this time lower. Trying to use his wrestling knowledge to secure a double-legg takedown. Vera met his charge by dropping her level even lower. Her arms snaking around his neck in a guillotine choke, but she modified it, using his own momentum to flip him over her hip while maintaining the choke, a combination her grandfather had developed in Vietnam when standard techniques proved insufficient.

She released him after two seconds of pressure, enough to dizzy but not damage, letting him gasp on his hands and knees while she addressed Hayes, who was struggling to stand on weakened legs. He threw a desperate grab for her uniform, trying to use his weight advantage, but she captured his extended arm in a standing kimura that her grandfather called the crow’s wing.

The shoulder lock bent at angles that gave her complete control despite the size difference. Morrison, still wheezing from the solar plexus strike, attempted to tackle her from behind, a move that might have worked if she hadn’t spent years training blind, grappling with her grandfather in pitch dark bayou nights.

She released Hayes and dropped to one knee, using Morrison’s momentum to throw him over her shoulder in a modified seo nudge that planted him hard in the sand. Before he could recover, she transitioned to a rear naked choke, her forearm across his corroted arteries while her legs controlled his body, not squeezing to unconsciousness, but demonstrating the position for exactly 4 seconds before releasing.

Hayes tried one more attack, a wild swing born of desperation, but Vera caught his wrist and executed an iikido inspired redirect that sent him spinning into Tella, both men collapsing in a tangle of limbs. The entire engagement had lasted 38 seconds from first contact to final technique. She stood in the center while all three candidates struggled to breathe, her uniform barely disheveled, not even winded from the demonstration.

Master Sergeant Rodriguez arrived within minutes, having monitored the situation from the observation tower, allowing it to proceed as what he’d later term a teachable moment for everyone involved. The three candidates received formal counseling statements for attempting to haze an instructor and mandatory additional training on army values and professional conduct.

The video spread through military social media channels despite attempts to contain it, reaching 4 million views in 72 hours before being flagged for OPSE review. The Fort Benning commanding general didn’t visit personally, but sent his command sergeant major to observe Vera’s first official class, where she used the morning’s incident to demonstrate the difference between sport fighting and combat reality.

She broke down each technique in detail, explaining how proper application required understanding of anatomy, physics, and most importantly, restraint, the difference between controlling a threat and creating a casualty. Teller approached after that first class, his pride replaced with genuine curiosity, asking if she would provide additional instruction on the techniques that had neutralized him so efficiently.

Within 4 months, her combatives curriculum had been adopted across all IBLC iterations with video modules of her demonstrations becoming required viewing for all infantry officers. She received an army commendation medal from the brigade commander for innovations in combatives training that reduced training injuries by 40% while improving practical proficiency scores.

Morrison became one of her most dedicated students. Later crediting her instruction with saving his platoon sergeant’s life during a close quarters engagement in eastern Syria where weapons had failed and hands became the only option. Hayes wrote her a letter from his first duty station at Fort Hood, thanking her for teaching him that real strength meant knowing when not to use it.

The program she developed incorporated her grandfather’s techniques into official army doctrine, ensuring his legacy would train warriors for generations. She kept teaching, her classes always full, producing officers who understood that combat effectiveness came not from size or strength, but from knowledge, timing, and the wisdom to apply minimum force for maximum effect.