October 12th, 1945. A church basement hall, Medford, Oregon. The air smelled of floor wax, boiled milk, and damp wool. Nurse Chio Oricasa kept her hands locked together in the lap of her oversized US Army issue work shirt.

The other 19 women sat rigid on the wooden benches, their backs straight, their gaze fixed on the heavy earthnware bowls before them. A steaming, opaque white liquid filled the bowls. It was thick, studded with pale chunks of potato and dark flexcks of herb. It smelled wrong, a faint, briny odor of the sea, trapped beneath the unfamiliar richness of celery and warm cream. A smiling American woman in a floral print dress, her hair pinned in soft victory rolls, set a small wax paper packet beside Chio’s bowl. saltine crackers. Chio stared at the soup.

It was the color of sickness, of pus, of bleached bandages. Her stomach clenched, fighting the memory of the other sea, the one that stank of diesel, scorched metal, and the decay she had failed to hold back. Her friend Emmy whispered beside her, her voice barely audible. It is milk from a cow. Chio picked up the heavy utilitarian spoon.

This, she thought, is what the victors eat. The psychological barriers were often stronger than the barbed wire. If you find these hidden moments of history compelling, consider subscribing and letting us know what country you’re watching from. 8 weeks earlier, Campair, Oregon. 8 weeks earlier, Campadare, Oregon. August 15th, 1945.

The silence of the high Oregon desert was absolute, broken only by the crackle hiss of the pole-mounted loudspeaker in the segregated women’s compound of Campadair. The 20 nurses stood in two perfect ranks on the dusty parade ground. They had been ordered to assemble at Osuo. No reason was given. Chio Oricasa, former head nurse, stood at the front, her gaze fixed on the peeling white paint of the messaul wall.

She ignored the sweat, tracing a line down her spine, chilling her beneath the coarse US Army issue cotton shirt. Her posture was immaculate. She was a nurse of the Imperial Army. She would show the Americans nothing. The hissing stopped. It was replaced by a voice, high, nasal, and reciting in a formalized Japanese that felt centuries old.

It was his voice, the Gyokuan Hoso, the voice of the crane. Chio’s blood turned to ice. She had heard the rumors whispered by the Ni guards. She despised, but she had refused them. Teiji Nooryaku, enemy deception. But that voice was unmistakable. She could not follow the archaic court language, but the meaning was carried in the weeping static, in the tremors she heard in the divine recording. Tyru Otataki otai enduring the unendurable.

The recording stopped. The hiss returned. For a full minute, no one moved. The universe had ended. The sky was still blue. A guard by the gate, a young private from Ohio, lit a cigarette, indifferent. Then the sound began. It was not a whale. It was a low animal keening.

To Chio’s left, nurse Wadonabi crumpled, her hands clawing at the dust. Uso, Uso, a lie, a lie. Beside her, Emmy, her youngest nurse, began to sob, her shoulders shaking violently. the foundation of Chio’s world, the divine mandate, the honor of Gyokusai, the justification for the rotting limbs in Saipan, for the friends who had jumped from the cliffs had just been declared null. They were not martyrs.

They were just prisoners, the survivors of a lost cause. “Tate,” Chio commanded. Her voice was brittle, sharp. “Stand up.” The women flinched, the sobbing cut short. The American guard looked over, curious. Chio’s mind was terrifyingly clear, latching on to the only structure left, protocol. The war is irrelevant, she said, her voice a rasp.

We are nurses of the Imperial Army. We will maintain discipline. We will shame them with our conduct. She was a ghost addressing other ghosts and the enemy watching from the wire was simply bored. Chio ignored the American guard’s retreat as the Gyoku on Hoso ended. The prisoners were her responsibility. She turned, her shadow cutting across the weeping women in the dust. Her gaze found Emmy.

The girl, Emmy was only 20, was rocking on her knees, her face buried in her hands, her shoulders heaving in uncontrolled gulping sobs. It was a disgusting sound. It was the sound of defeat. Watnab, Emmy, stand, Kio ordered. Watnab flinched and forced herself up, her face a mask of stret.

But Emmy did not respond, lost in her grief. The other women watched, their eyes wide with a mixture of fear and despair. “Nurse Emmy,” Chio said, her voice dropping to the flat, cold tone she reserved for the operating theater when a surgeon made a mistake. Emmy continued to sob. Chio stepped forward. She did not drag the girl up.

She did not shake her. She simply drew back her hand and struck Emmy hard across the face. The crack of the slap echoed with unnatural clarity in the dry air. Emy’s sobs choked off in a sharp gasp. She froze, her hand rising slowly to her stinging cheek, her eyes fixed on Chio in stunned disbelief. Chio said, her Japanese precise and coldet.

Emmy scrambled to her feet, wiping her face with the back of her dirty sleeve. She snapped to attention, trembling, but silent. Chio surveyed the other 19 women. Their grief had evaporated, replaced by the familiar, rigid terror of her authority. Good terror was a structure. Terror was better than shame.

We will clean the barracks, Chio announced. We will report for mess at 12. So Paul, we will observe evening roll call at 17. We are not savages. She had channeled the entirety of her own screaming broken psyche into that single violent act of discipline. She had pushed her her shame at being alive, at being captured, at hearing her god surrender deep down into a cold, dark place.

In itsstead, she erected the framework of the Imperial Nurse Corps. She turned and marched back to the barracks, the women following in a shuffling, terrified column. She felt nothing but the crunch of gravel under her boots. She did not see the US Army jeep pull up to the compound gate.

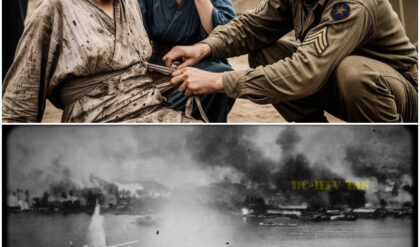

She did not see the Nissi soldier step out, a clipboard in his hand, his face a complex mask of duty and distaste. They were scrubbing the barracks floor when the Nissi soldier entered without knocking. He was short, but his US Army fatigues were sharply pressed. He carried a clipboard and an expression of profound weariness.

His eyes, Chio noted with disgust, were their eyes. But he wore the uniform of the enemy. The women froze, their rags dripping soapy water onto the pine boards. Kangucho Oricasa, he said. His Japanese was fluent, formal, with a faint, bizarre accent. Oricasa Chiosan Chio rose slowly from her knees. She wiped her hands on her trousers, her face devoid of expression. This, she thought, was the ultimate degradation.

Not just a conqueror, but a traitor to the blood. A dog, an enu. I am Sergeant Kenji Tanaka, Military Information Service. He continued in Japanese. The war has concluded. I am here to begin processing your repatriation paperwork as required by the Geneva Convention. He held out the clipboard and a pencil. Chio stared at the pencil.

It was yellow with a pink eraser. It was such a small civilian object. She looked past it, past the clipboard, past his uniform to a point on the wall just over his shoulder. He sighed. The sound of a man who had been through this ritual a hundred times. Oricasan, I need your name, your civilian prefecture, and your next of kin.

Chio did not move. The silence in the barracks stretched, punctuated only by the drip of water. Emmy was holding her breath. Sergeant Tanaka’s patience snapped. “Look,” he said, his voice hardening. “This is not a request. This is for your own Enzen, your safety. We need to know who you are.” Chio finally met his gaze.

Her eyes were as flat and cold as obsidian. She spoke in the clipped, heavily accented English she had learned from a missionary in Nagasaki. I do not understand, she said. Tanaka stared at her. The air crackled. He knew she understood. She knew. He knew. It was a perfect precise act of psychological warfare.

She was denying him his language, his heritage, his purpose. She was erasing him. “Do not make this difficult, nurse,” he warned, switching to English. “I am prisoner,” Chio replied, her voice flat. You are soldier. I do not understand. Sergeant Tanaka’s jaw tightened. He looked around at the other women who stared at the floor, unified in their silent defiance.

He had no authority here. Chio had checkmated him. He slammed the clipboard against his thigh. “Fine,” he hissed. “Have it your way.” He spun on his heel and marched out, the screen door slamming shut behind him. Chio turned back to her bucket of water. “Soji,” she commanded, clean. She had won.

She had refused to be documented, refused to be processed. This small, bitter victory solidified her control, but it also, unknown to her, marked her as a problem to be solved by the camp administration. 2 days later, Sergeant Tanaka returned. He did not enter the barracks. He stood at the compound gate, holding it open for a civilian.

Chio watched from the window, her hands still. The woman was tall, in her late 40s, and wore a floral print dress in bright offensive colors, yellow and blue. Her hair was pinned up. She carried a small cloth bag. She was, Chio registered with a cold pang, the enemy.

She was the victor, the mother, the wife of the men who had burned their cities. “Nurse Oricasa,” Tanaka called out, his voice strained. “This is Mrs. Albbright. She is from a local church group.” Chia walked slowly out of the barracks, the other women gathering behind her like nervous shadows. She stopped 10 ft from the wire fence. Mrs. Albbright stepped forward, her hands clasped. She smiled.

It was a wide, nervous expression that showed too many teeth. “Hello,” Mrs. Albbright said, her voice soft. Tanaka translated, but Chio understood the English. “We, the community, we just wanted to welcome you.” “Welcome?” The word was absurd. “This was a prison.” Mrs. Albbright fumbled in her bag and pulled out a small rectangular object wrapped in brown and silver foil.

a Hershey’s chocolate bar. “We thought you might like this,” she offered, holding it out through the gap where the gate stood open. “A small taste of America.” Chio’s eyes flicked from the woman’s smiling face to the chocolate bar, then to Tanaka’s impassive mask. She saw the tactic instantly. The Ni Enu had failed to break them with paperwork.

Now they were sending a woman armed with sugar and pity. Pity was the most corrosive weapon. It was an acid that dissolved and left only the weakness of the animal. To accept pity was to admit she needed it. To accept the chocolate was to confirm she was a starving, defeated creature. Chio stood perfectly still. She did not look at the chocolate again.

She simply stared at Mrs. Albbright, her black eyes reflecting the empty Oregon sky. She did not move. She did not speak. The smile on Mrs. Albreight’s face faltered. The woman’s hand holding the offering trembled slightly. The silence became a physical weight. Defeated, Mrs. Albbright slowly withdrew her hand. Her face flushed with embarrassment.

“I I see,” she stammered. She looked at Tanaka for help, but he only watched Chio. With a look of pained resignation, Mrs. Albbright stepped back and carefully placed the chocolate bar on top of a wooden fence post. Perhaps later, she murmured. As she and Tanaka turned to leave, Chio felt no triumph. She only felt a cold, hard certainty.

The woman had been rebuffed, but she had not given up. This was not the end. It was the beginning of a different kind of assault. The chocolate bar remained on the fence post for a day, untouched. It swelled slightly in the afternoon sun, then grew brittle in the cold desert night.

A bird eventually pecked at it, found it alien, and left it alone. It was a rotting monument to their failed assault, but Chio knew the assault was not over. On the third day, Sergeant Tanaka returned. This time he did not pause at the gate. He stroed directly to the barracks and pinned a sheet of paper to the door.

Chio met him on the steps, barring his entry. “What is this?” she demanded, using her sparse English. “It’s an invitation, nurse,” Tanaka said, his tone flat and official. “He was no longer trying to be Japanese. He was all US Army.” “Mrs. Albbright and the Medford First Presbyterian Church formally invite the residents of this compound to a friendship meal.

October 12th, 1,800 hours. He tapped the paper. Attendance is expected. Chio read the typed words, “Friendship meal. Postwar friendship.” The language was soft, but the paper was a military requisition. “We are prisoners of war,” Chio said, her voice dropping. reverting to the formal Japanese she had denied him before.

She was no longer playing a game. She was issuing a counter order. Tanaka flinched, surprised by the sudden switch. We are not guests, Chio continued, her words precise. We are not part of their community. We are subjects of the emperor detained by your army. We do not require friendship. She looked past him at Emmy and the other women watching from the doorway. She was speaking to them as much as to him.

She was reinforcing the wall. “Tell the commonant,” Chio said, her voice final. “We refuse. We are prisoners of war, not children to be fed.” “This was a calculated risk. She was invoking the Geneva Convention, testing the limits of her rights as a non-combatant prisoner. She was betting that they could not force her to accept a social invitation. A flicker of something.

Was it frustration or grudging respect? Crossed Tanaka’s face. He had his orders, but she had just cited international law. “I will relay your message, nurse Oricasa,” he said stiffly. He turned and left. Chia watched him go, feeling the first cold rush of righteous purpose she had felt since Saipan. She had drawn a line.

She had defended her women from the enemy’s pity. Now she would see if the enemy respected that line. Chio’s victory lasted less than an hour. She heard the heavy tread of combat boots on the gravel path. A different sound from Tanaka’s lighter step. A shadow fell across the barracks doorway. Captain Miller, the Camp Commandant, filled the space.

He was a large man, smelling faintly of Chesterfield, cigarettes and sweat. He held his helmet under his arm, his garrison cap pushed back on his thinning hair. He looked annoyed. “Nurse Oracasa,” he said, not bothering with pleasantries. “Sergeant Tanaka stood just behind him, looking at the ground. Chio stood, her posture rigid.

” Captain, Sergeant Tanaka informs me, Miller said, his voice flat, that you have refused an invitation from the local community. We are prisoners of war, Captain. Chio stated, her English precise. Not guests. The Geneva Convention. The convention. Miller cut her off, taking a step inside.

The women against the far wall flinched. The convention says, “I’m responsible for your welfare. Mrs. Albbright is a very respected member of the Medford community. She’s gone to a lot of trouble to offer a kind gesture. My welfare includes keeping the locals happy.” He looked around the bear clean barracks. “Frankly, nurse, I am tired of the games.

Tanaka can’t process you. You won’t cooperate. This non-compliance ends now. Chio’s stomach tightened. This was not a negotiation. This is not a request, nurse, Miller said, his voice dropping, becoming hard. It is a direct order from the ranking military authority of this camp.

You and your women will be cleaned, dressed, and ready for transport on October 12th, 18 mu hours. You will attend this meal. You will be polite. Is that clear? The kindness was now a bayonet at her throat. Chio stared into his pale, impatient eyes. She saw no malice. She saw only the absolute indifferent weight of his power. Her legal argument, her defiance, her They were meaningless. She was a prisoner.

He could order her to eat and she would eat. The humiliation was deeper than any physical blow. It was the realization that her resistance had been an illusion he had permitted. Her voice was barely a whisper. It is clear, Captain. Good. Miller nodded, satisfied. He turned and left, his boots crunching on the path.

Tanaka lingered for a moment. He wouldn’t meet her eyes. Be ready, Oricasan, he murmured in Japanese, then followed his commander. Chio stood immobile for a full minute, hearing the jeep engine start and fade. She had failed. She had lost the battle. She had led her women into a new, more profound defeat.

For the next two days, Chio enforced a new, colder discipline. She had failed to protect them from the order, so she would protect them from the act. “We will march in formation,” she instructed the women on the morning of October 12th. The air was cold, carrying the sharp scent of pine and distant woodsm smoke. We will not speak unless spoken to. We will not accept anything beyond what is placed before us.

We will show them nothing. We will remain imperial nurses. She was met with dull nods. The women were exhausted. The fight had gone out of them, replaced by a hollow obedience. That afternoon, as Chio was inspecting their issued wool shirts, ensuring they were clean at least, Emmy approached her cot.

The girl looked thinner than ever, her skin a pale papery yellow over her cheekbones. “Chio son,” Emmy whispered, her eyes fixed on the floor. “What is it, nurse?” Chio asked, not looking up from folding a shirt. I uh Emmy hesitated, her hands twisted in the fabric of her trousers. I must confess something shameful, Chio paused. Go on.

The meal, Chiosan, Emmy whispered, her voice cracking. I uh I am glad we are going, Chio’s head snapped up. Glad? The word was venomous. I am just so hungry, Emmy breathed. And now the tears she had held back for days began to stream down her face. The bread. I cannot eat the bread. It is like sawdust. I miss rice. I miss anything warm.

I She pressed a hand to her stomach. I am always empty. Chio stared at her. This was the ultimate betrayal of the spirit. This was the animal weakness she had fought so hard to eradicate. Her first instinct was to strike her as she had before, to slap the weakness away, but she couldn’t. She looked at Emy’s trembling hands, the blue veins visible beneath the transparent skin.

She saw the soores at the corner of the girl’s mouth, malnutrition. Chio’s rigid focus on spiritual honor, on had completely blinded her to the simple physical decay of the woman in front of her. Emmy wasn’t a weak-willed subject. She was a starving human being.

This realization brought a profound, sickening wave of cognitive dissonance. Chio felt both disgust at the weakness and a terrible, unwelcome ache of pity. She had been trying to save Emy’s soul, but her body was failing. “You will sit next to me,” Chio said, her voice flat, betraying nothing. You will not show them your hunger. You will eat only what I eat.

Understood? Emmy nodded, wiping her face. Hi, Kangafucho. Chio’s motivation had fractured. It was no longer a simple battle of wills. Now she had to protect Emmy, not just from the enemy’s pity, but from her own body’s betrayal. At 17:45, a US Army deuce and a half truck rumbled to the gate. Captain Miller was taking no chances.

“Sergeant Tanaka and two armed guards, their M1 rifles slung casually over their shoulders, waited.” “Line him up, Sergeant,” Miller ordered. Chio led the women out, her face a stone mask. She positioned Emmy directly behind her. It’s only half a mile, Tanaka said to her quietly in Japanese, gesturing to the truck. It’s faster if we drive. Chio looked at the truck bed, open and exposed. We will walk, she said in English.

Miller overheard. Fine, walk. He shrugged, clearly not caring how they got there, only that they did. He got in his jeep and drove off toward the town. Tanaka, “Hi, Oricasan. march. They formed two columns. Chio at the head, Tanaka in front, and the two guards flanking them.

The moment they stepped outside the camp wire, the world changed. The air felt thinner, the sky too large. After a year, confined by fences, the open space was a psychological assault. They marched down the gravel service road and onto a paved street that led into the small town of Medford. It was the first time they had seen a civilian street since 1944.

A woman hanging laundry in her backyard froze, her hands full of clothes pins and stared. Two boys on bicycles stopped, their mouths open. Chio kept her eyes fixed on Tanaka’s back. Do not look. Do not engage. We are ghosts. They passed a gas station. A man in greasy overalls was working on the engine of a Ford truck.

He heard the rhythmic of their boots on the asphalt and looked up. His face unremarkable moments before, twisted into a mask of pure hatred. He wiped his hands on a rag, stood up slowly, and spat a thick wad of tobacco juice onto the pavement just short of the column. “Damn Japs,” he muttered loud enough for Chio and Tanaka to hear. Tanaka flinched, his neck turning red, but he did not stop.

The guards tensed, their hands moving closer to their rifles, not to defend the prisoners, but to control them. Chio felt Emy’s hand brush her back. a small terrified tremor. The man’s hatred was a physical thing, hot and acidic. It burned away Chio’s fragile new pity for Emmy and replaced it with a cold, familiar rage. Her confirmation bias locked into place.

This was the true America, not Tanaka, not the commonant, and certainly not the smiling woman with her chocolate. This was the enemy. Mrs. Albbright’s kindness was a lie. a trap. This meal was not friendship. It was a public spectacle of their humiliation. The man’s spit was still wet on the pavement as they turned the corner toward the church. Chio’s resolve hardened into ice.

They were walking into a fight. Sergeant Tanaka opened a heavy wooden door, revealing a set of stairs descending into a brightly lit basement. The smell hit them first. It was not the smell of the church upstairs, old wood and hymn books. This was a thick complex odor. It smelled of boiled milk, floor wax, celery, and a faint briny tang of the sea.

Chio’s stomach clenched. The smell of the sea was the smell of death. It was sipan. It was the transport ship. The stench of diesel, vomit, and the decay she had failed to hold back. S she whispered down. One by one they descended the steps emerging into a large low-sealing hall. The walls were painted a pale sterile yellow.

Long wooden benches were arranged before tables covered in white paper. And the women, there were perhaps a dozen of them, American civilians. They were all smiling, their hair pinned up in soft rolls, their dresses floral and bright. They looked like the woman who had offered the chocolate but multiplied. At the front of the room, Mrs.

Albbright stood behind a long table, beaming with a terrifying, nervous energy. Beside her was a massive, steaming silver tin. “Welcome, welcome,” Mrs. Albbright said, clapping her hands together softly. Please sit, sit. Chio led her column to the nearest bench. The wood was smooth, polished. They sat as one, backs perfectly straight, hands folded in their laps. 20 statues in drab olive green.

The American women began to move, their efficiency betraying their nervousness. They placed heavy earthnware bowls in front of each prisoner. Mrs. Albbright picked up a large ladle. “We wanted to make you something special,” she announced to the silent room, her voice echoing slightly. Tanaka translated, his voice monotone. “This is a New England clam chowder. It’s It’s a taste of our home.

” She dipped the ladle into the tin and filled the first bowl. It was an opaque, heavy white liquid, studded with pale chunks of potato and dark flexcks of herb. A woman in a red dress placed the steaming bowl in front of Chio. Chio stared into it. It was the color of sickness, of pus.

The briny smell was stronger now, trapped beneath the unfamiliar richness of the cream. Another woman placed a small wax paper packet beside the bowl. Saltine crackers. Emmy beside her made a small choked sound. Chio felt the walls of the trap close in. The smiles were the cage bars. The warm milky air was the anesthetic, and the bowl of white liquid was the poison.

The standoff had begun. The silence in the basement was absolute. It was heavier than the smell of boiled milk. The 20 Japanese women sat immobile, their bowls steaming untouched. The dozen American women stood frozen by the walls, their smiles locked in place, becoming painful. This was the new battlefield, a white ceramic bowl.

Chio kept her gaze fixed on the surface of the soup. She saw the oily sheen of the cream, the dark green flexcks of herb. It was a landscape of the enemy’s world. To eat it was to surrender. Beside her, Emmy made a small sound, a tiny intake of breath. Chio turned her head slightly. Emmy was staring at the bowl, but her eyes were unfocused. Her skin was a ghastly gray.

She was swaying on the bench, intoxicated and sickened by the rich aroma that her starving body craved. She was going to faint. She was going to humiliate them all. Chio’s gaze snapped from Emmy to Mrs. Albbright. The American woman was watching them, her hands twisting her apron. She was not a triumphant victor. She was a terrified hostess.

The calculation in Chio’s mind was instantaneous. To refuse was impossible. Miller’s order was absolute. To faint, as Emmy would, was shameful. To eat. If she ate, it could not be acceptance. It had to be a duty. She was the kangapucho, the head nurse. It was her responsibility to test the food to ensure it was not poisoned, to protect her women.

She reframed the act of surrender as a final act of command. Her hand, steady, moved from her lap. It grasped the heavy utilitarian spoon. The metal was cold. She pushed the spoon through the thick liquid, breaking the surface. She raised it. The white fluid dripped slowly. She brought it to her mouth. The room held its breath.

The clink of the metal spoon against her teeth was the only sound, as loud as a rifle shot. She closed her lips around the spoon. The soup was in her mouth. She held the soup in her mouth. Her entire nervous system braced for poison, for disgust, for the taste of defeat. There was no poison. The dominant flavor was not the briny traumatic sea. The sea smell had been a phantom, a memory triggered by the name.

The reality, now on her tongue, was different. It was salt. It was the mild, earthy taste of potatoes. And beneath it all, the rich, impossibly smooth flavor of cream. It was warm. The warmth radiated from her tongue down her throat and into the cold, empty pit of her stomach. It was the first truly warm thing she had tasted in over a year.

Her indoctrination screamed propaganda. Her trauma screamed shame. But her body, a starving pragmatic animal, screamed louder, more. Her hand, acting with a valition of its own, dipped the spoon again. The second spoonful confirmed it. The small chewy pieces were just food. The third spoonful was good.

She felt a stinging sensation behind her eyes. It was appalling. She was being defeated by dairy. She tore her gaze from the bowl and looked at the small wax paper packet. Saltine crackers. She tore it open with trembling, clumsy fingers. The cracker inside was a perfect pale square, perforated with tiny holes.

Mechanically, she put a corner of it in her mouth. It was nothing. It was dry, salty, brittle flour. It had no ideology. It had no honor or shame. It was simply a cracker. She put the cracker into the soup. It softened instantly. She ate it. The combination of the neutral, salty crunch and the warm, creamy liquid was a profound biological shock.

It was nourishment, plain and simple. It was not a weapon. It was not pity. It was just food. The realization hit her with the force of a physical blow. Her entire complex psychological defense, the the discipline, the righteous anger had been bypassed by a simple biological truth. She was hungry. This was food.

The wall inside her mind, the rigid structure she had built to survive her shame, did not collapse. But a crack had formed, a tiny hairline fracture through which this alien warmth was now seeping. Her body had betrayed her. Her body had chosen to live. Chio slowly, very slowly, lifted her head. She looked up from the white bowl.

The room came back into focus, but it was altered. The light seemed warmer. The pale yellow walls no longer looked sterile, just painted. Her gaze traveled across the table to Mrs. Albbright, who was still standing by the terine watching her. Chio’s indoctrination was ready for the triumphant smirk, the look of condescension, the I told you so of the victor.

But that is not what she saw. Mrs. Albbright was not smiling. She was watching Chio’s face with an expression of profound naked anxiety. When Chio’s eyes met hers, the American woman started as if caught. A wave of visible relief washed over her face, so powerful it was almost comical. She gave Chio a small, hesitant, grateful smile.

Mrs. Albbright then picked up a small basket of saltine cracker packets from the table and tentatively pushed it toward the center closer to Chio. A simple offering. In that instant, Chio’s entire perception of the event recontextualized. This was not propaganda. This was not a power play by Captain Miller. This was a woman.

a woman in a floral dress who had spent all day boiling milk and potatoes, terrified that the strange, hostile women she had invited would hate her cooking. She was not a white devil. She was not a victor. She was just a person nervous about her soup. This realization offered no comfort.

It was in its own way more painful than the hatred from the man at the gas station. hatred. She understood this this simple, awkward, shared humanity was terrifying. It invalidated her entire framework for survival. She heard a small sound, a hesitant clink of metal on ceramic. Nurse Watanabe watching Chio had picked up her own spoon, then another. Chio turned her head. Emmy was still frozen, looking at Chio, waiting for permission, her eyes begging.

Chio looked at her friend at the pale skin, the soores, the desperate hunger. She gave a single sharp nod. Eat. It was an order, the same order she had given a hundred times in the field hospital. But this time, it was not an order to maintain discipline. It was not an order to prepare for an honorable death. It was in order to