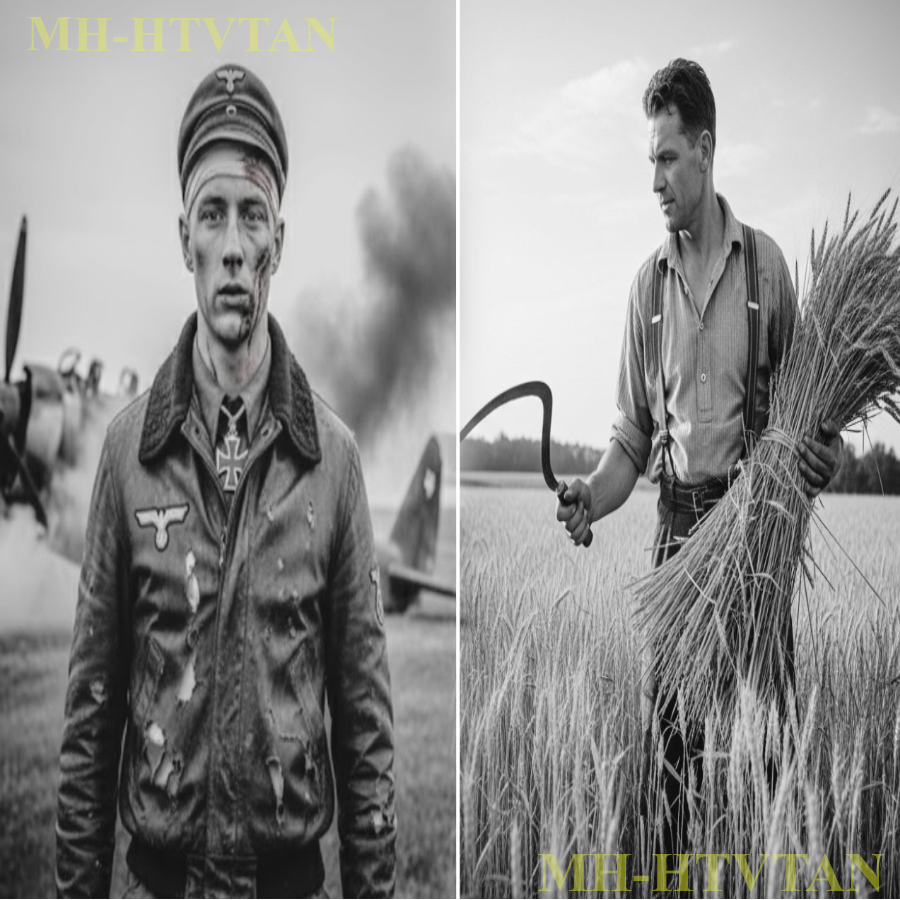

The American military police had just discovered six German fighter pilots hiding in Ernst Vber’s barn. The old Bavarian farmer was certain he would be executed for sheltering enemy soldiers. It was May 8th, 1945. Germany had surrendered that morning, but Ernst knew surrender did not guarantee mercy.

The Americans did not line Ernst against a wall. They did not burn his farm. Instead, they grabbed farming tools and spent the afternoon helping him harvest wheat. This is the story of how a single act of humanity in the ruins of Nazi Germany helped build an alliance that has lasted 80 years. And it started with an old farmer, six desperate pilots, and American soldiers who chose mercy over vengeance.

Ernst Weber’s hands trembled as he watched the convoy of American jeeps roll up his dirt road. Four vehicles, eight military policemen, their boots crunched on gravel as they stepped out sunglasses reflecting the morning Sunday. Behind him, hidden in the barn under hay bales, and behind a false wall he had built 3 weeks earlier, were six Luftwaffa pilots, young men who had crashed their fighters in the surrounding Bavarian fields as American forces swept through southern Germany like an unstoppable flood. Ernst had fed them, sheltered

them, lied to American patrols twice already. His neighbor Fron had whispered the stories. A farmer two villages over, found housing Vermached soldiers left dead in the road as a warning. Were the stories true? Ernst did not know. That was the curse of living through 6 years of war and two years of Nazi control before that.

Truth had become impossible to separate from propaganda, from fear, from the desperate hope that you were not on the wrong side of history. His wife Margaret stood beside him in the doorway. At 72 and 68 years old, respectively, they looked ancient. Three sons gone, one killed at Stalenrad, one missing in France, one captured by the Soviets.

They had nothing left to lose except each other. Margaret grabbed Ernst’s hand. Her touch felt like a goodbye. Her vber. The lead MP was young, maybe 25. He spoke German with an American accent that made the harsh consonant sound almost gentle. Erns nodded. His throat had closed completely. The American gestured toward the barn.

Five words that stopped Ernst’s heart. We know they are in there, sir. This was it. The end. Ernst’s mind raced through what would come next. They would shoot the pilots, then they would shoot him for hiding enemy combatants right up until Germany’s final surrender. “The Americans had no reason to show mercy.” “How many?” the lieutenant asked, pulling out a notepad.

Erns considered lying, considered everything, then decided truth was all he had left. “Six,” he whispered. “Six pilots. They crashed over three weeks, different times. They had nowhere else to go. The American Ernst would later learn his name was Lieutenant James Cooper from Ohio wrote something down. Ernst waited for rifle barrels to rise, waited for the order to kneel.

Instead, Cooper looked at the barn, then back at Ernst. Are any of them injured? The question was so unexpected that Ernst answered automatically. Two. One has a broken leg we set poorly. Another has burns on his hands and face. Cooper turned to another MP. Get Davis. Tell him we need medical supplies. Ernst’s confusion was total.

Medical supplies for German pilots for the enemy. Inside the barn, Oberlutnickl Klaus Richter heard the vehicles and positioned his men behind hay bales. At 23 years old with 74 confirmed kills, Klouse understood military mathematics. They had one Luger pistol, six bullets, eight American MPs outside, probably with moan carbines, probably with grenades. This was not a fight.

This was suicide. The barn door opened. Sunlight flooded in. We surrender, Klouse called out in English. We are unarmed. The lie was necessary. He had hidden the Luger in the hay. But as the Americans entered, weapons ready but not raised, Klouse made a decision that would save all their lives, he stepped forward, hands raised, and spoke the truth.

We have one pistol hidden. We will not use it. We want to live. Lieutenant Cooper stopped, studied Claus’s face, then nodded. Smart man, where is the pistol? Klaus retrieved it from the hay and handed it over. Magazine removed. Cooper took it, examined it, then did something Klouse never expected. He smiled.

74 victories? Cooper asked, gesturing to the Knight’s Cross at Klaus’s throat, the medal given to elite fighter aces. That is impressive flying. Klouse did not know how to respond. Was this mockery, a trap? Cooper’s expression shifted to something sadder. My brother was a navigator on a B17 shot down over Berlin last November.

Klaus felt ice in his stomach. I am sorry. Yeah, Cooper said quietly. Me, too. But that is over now. The war ended this morning. He raised his voice to address all six pilots. You men are prisoners of war. You will be treated according to the Geneva Convention. That means food, medical care, and transport to a PW facility.

Anyone injured gets priority treatment. One of the younger MPs, Klouse would learn he was Private Rodriguez from Texas, looked at Hinrich Becker and muttered, “Jesus Christ, kid is barely old enough to shave.” Heinrich was 19, his face wrapped in makeshift bandages from burns. He had been shot down on his fourth mission, still terrified, still expecting death.

Instead, Corporal Davis, the American medic from Arkansas, knelt beside Heinrich and opened his medical kit. Let me see those burns, son. What happened next violated everything Klaus Richter understood about war. Davis unwrapped Heinrich’s bandages with practice efficiency. The burns were infected. Ernst had done his best with limited supplies.

But he was a farmer, not a doctor. Davis examined the raw skin, wincing. These need proper cleaning. It is going to hurt. I am sorry. He was not mocking. He was actually apologetic to an enemy pilot who might have killed Americans just days before. Davis applied antiseptic. Heinrich hissed in pain but did not cry out. The American medic worked carefully, talking the whole time in broken German, explaining each step.

When he finished bandaging the burns properly, he handed Hinrich two white pills. “Sulfa drugs,” Davis explained to Klaus’s suspicious look. Antibiotics prevents infection. You will get morphine later if the pain gets worse. He moved to Verer Ko, the pilot with the broken leg. Ernst had tried to set the bone, but Verer had been suffering in near silence for 2 weeks.

Davis examined the leg and shook his head. This needs a real doctor. We will get you to the field hospital in Lansburg. Klouse found his voice. You are taking him to an American hospital. Geneva Convention. Cooper said simply, as if that explained everything, “Prisoners of war receive medical care equivalent to our own troops. You are Ps now, not enemies.

” There is a difference. The distinction seemed impossible. For 6 years, Klaus had been taught that Americans were barbaric, that they executed prisoners, that surrender meant torture and death. Yet here was an American medic treating German burns with American medicine, speaking gently to a German teenager who might have shot down his friends.

Outside, Lieutenant Cooper handed Ernst Weber a piece of paper. Receipt for the food you provided to these men. The US Army will reimburse you. Takes a few months to process, but you will receive payment. Ern stared at the paper like it contained ancient hieroglyphics. You are paying me for feeding your enemies.

Cooper’s expression softened. You are not going to be punished. Hair Vber. You gave humanitarian aid to wounded soldiers who could not fight anymore. That is not a war crime. That is human decency. He paused then added something that Ernst would remember for the rest of his life. My grandfather came from Germany, village called Louderderbach.

came to America in 1887 with nothing but hope and a willingness to work. America gave him a chance. He built a farm in Ohio. Raised my father. Raised me. Cooper gestured at the farmhouse that had stood for two centuries. You are not my enemy, her Vber. You are a farmer, a father. You showed mercy when you did not have to. If we are going to build a better Germany, a Germany that can be our allies someday, it starts with men like you.

Ernst felt tears running down his weathered face. He did not try to stop them. The propaganda told us you would destroy everything, burn our farms, enslave our people,” Cooper nodded. “They told us things about you, too. Most of it was lies.” His expression darkened. “Some was not. The concentration camps.” He stopped, shook his head.

“But you are not responsible for that. You are just a man who tried to save lives. Over the next 3 hours, something remarkable unfolded in Ernst Weber’s farmyard. The Americans processed the six pilots for transport to the P facility at Mooseberg, but they did not treat them like dangerous prisoners. MPs sat with them in the shade, shared American cigarettes lucky strikes that Klaus had not tasted in 3 years.

Sergeant Kowalsski, whose grandparents had immigrated from Poland, translated jokes that made everyone laugh despite everything. Klaus found himself on a hay bale next to Lieutenant Cooper. Both smoking 173 missions, Klouse said when Cooper asked about his combat record. “Then because honesty had become the currency of this strange new world.

“How many bombers did you lose to pilots like me?” “Too many,” Cooper replied. They sat in silence. Two young men who had spent years trying to kill each other’s brothers, now sharing tobacco in the ruins of a war neither had wanted. Private Rodriguez noticed Ernst’s fields. The wheat was golden, ready for harvest.

But the old couple could not possibly bring it in alone. Their sons were gone. Their labor was gone. The wheat would rot. Rodriguez approached Cooper. Lieutenant, the old man’s crops are dying. Cooper looked at the wheat, then at Ernst, then at his watch. How long to process the PWS and get them loaded? 30 minutes, sir. Cooper made a decision that Klaus Richtor would tell his grandchildren about 60 years later.

After they are loaded, I want four volunteers to help her Vber with his harvest. We have got 3 hours before we need to report to Munich. Let us use them properly. Klouse spoke up. We will help. Cooper turned. You are prisoners. We are also farmers. Most of us grew up working fields like this before the Luftwaffa.

Klouse gestured at the other pilots. If you are feeding us and treating our wounded, the least we can do is help the man who sheltered us. Cooper considered this. You work under guard. Anyone runs, everyone pays. Clear? Clear. Klouse agreed. Where would we run anyway? The war is over. Germany is in ruins. At least here there is honest work and good company.

And so it happened. Four American MPs and six German fighter pilots working side by side in a Bavarian wheat field under the May sunshine. The Americans removed the pilots handcuffs. They provided water from their cantens. When young Johan shot down on his fourth mission, still traumatized, collapsed from exhaustion.

It was Private Rodriguez who helped him to shade and made him rest. Easy, kid. War is over. No more rushing. At midday, Ernst brought bread and cheese. Margaret made her sats coffee from roasted acorns. Real coffee had been impossible to find for 3 years. The Americans pulled out actual American coffee from their rations and shared it around.

Klaus Richtor tasted real coffee for the first time since 1942. The flavor hit him with such force that he had to turn away so the others would not see his tears. Such a small thing. Such an enormous gift. They worked until sunset approached. 3/4 of Ernst wheat field was cut, bundled, and ready for threshing.

More than Ernst and Margaret could have accomplished in two weeks alone. As they loaded tools back into the barn, Sergeant Kowalsski pulled out his personal camera, not official Army equipment, but one he had carried through the entire war. For memory, he explained. So we remember that even in the worst times, enemies can become something better.

He gathered everyone together in front of the farmhouse. Ernst and Margaret in the center, six German pilots in their Luftvafa uniforms, eight American MPs in their US Army patches, all of them together actually smiling. The photograph would survive 80 years. It would appear in history books, museums, documentaries about reconciliation.

But in that moment, it was just men who had survived, grateful to be alive, grateful for unexpected friendship. What happened at Ernst Weber’s farm was not unusual. It was American policy and it was strategic genius. General Dwight Eisenhower had issued explicit directives. German PWS would be treated according to Geneva Convention standards, not as subjects for revenge.

The reasoning was as much strategic as moral. George Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, understood something Nazi leadership never grasped. Wars end, but nations remain. By 1945, it was already obvious that the real enemy was the Soviet Union. If America wanted Germany as a cold war ally, they needed to win German hearts, not just German surrender.

The contrast with German treatment of Allied prisoners was stark and documented. American and British PWS in German camps faced systematic starvation, inadequate medical care, and forced labor that violated every article of the Geneva Convention. Soviet PW s fared even worse. Nearly 60% died in German captivity, often from deliberate starvation or execution.

Meanwhile, German Ps and American custody had a survival rate above 94%. They received the same food rations as American troops. They worked for wages. They received mail from home. Many even gained weight in captivity, a fact that shocked Germans when their soldiers returned home healthier than when they had left.

This was not naive soft-heartedness. This was long-term strategic thinking that would pay dividends for eight decades. The numbers told their own story. Of approximately 380,000 German PSWs held in the United States, fewer than 1% died in captivity, most from injuries sustained before capture or illnesses that could not be treated even with medical care.

Compare that to American Ps. 37% mortality in Japanese custody, 12 to 15% in German custody, mostly in the final chaotic months when supply chains collapsed. But the statistics that truly mattered came later after the war ended. In 1948, when the Berlin Airlift began and Soviets blockaded the city, former German PWS volunteered to help unload American supply planes.

Men who had fought against America now worked alongside Americans to save German civilians from Soviet starvation tactics. By 1955, West Germany joined NATO. Former mortal enemies became formal military allies in just 10 years. And when German leaders were asked how that transformation happened so quickly, many pointed to their time as PWS, when they learned that American values were not propaganda, they were real.

They were practiced and they worked. Klaus Richter captured this realization in his diary that night at Mooseberg P camp. His words would be quoted in German history textbooks for generations. Today I understood that we lost this war before it even began. Not because America had more planes or tanks, though they did.

We lost because they fight for something that makes them stronger after victory than we could ever be in conquest. They fight to make friends of their enemies. We fought to make slaves of ours. There is no future in slavery. There is infinite future in friendship. The six pilots spent eight months in P camps across Bavaria.

Hinrich Becker’s burns healed without infection thanks to the sulfa drugs Corporal Davis had provided. Verer Ko’s leg was properly reset by American doctors. He walked without a limp for the rest of his life, something that would not have been possible without American medical intervention. Klaus Richter was transferred to a camp in Regansburg where German PWS were being trained in democratic governance and dennazification.

He wrote letters to Ernst Vber. American sensors reading them pass them along without redaction. Ernst received his first letter in August 1945. It said simply, “Thank you for your mercy. It saved more than our lives. It saved our souls. When I am released, I will repay this debt. By March 1946, all six pilots had been released.

Germany was ruins. Cities destroyed, economy shattered, 12 million displaced persons wandering through the rubble. The work of rebuilding seemed impossible. Klouse went home to his family farm in Thingia and found it occupied by Soviet forces. The difference between American and Soviet occupation became immediately, brutally clear.

He fled west across the border into the American zone and settled in Bavaria near Ernst Weber’s farm. He appeared at Ern’s door in September 1946, hat in hand. I owe you a debt, Klouse said. Let me work. Let me help rebuild what the war destroyed. For three years, Klouse worked Ernst’s farm alongside him.

They expanded operations, bought new equipment with Marshall Plan loans, prospered modestly in the way of men who work hard and live simply and trust each other completely. The other five pilots stayed in close contact. Hinrich Becker went to university in Munich on American scholarship money, part of the early Marshall Plan that would rebuild Germany into an economic powerhouse.

He became a doctor specializing in burn treatment. He often said that Corporal Davis had saved his life twice. Once by treating his burns, once by showing him that former enemies could become healers. Verer Ko became a mathematics teacher in Stogart, teaching for 37 years. He always told his students about the American soldiers who had properly reset his leg when they could have left him crippled.

That is the difference between civilization and barbarism. He would say civilization heals even its enemies. Barbarism destroys even its own people. Two of the pilots eventually immigrated to America in the 1950s. Sponsored by American veterans who had guarded them as Ps and had become genuine friends.

They settled in Ohio and Texas, raised families, and lived the American dream that their capttors had shown them was real. In 1961, when the Berlin Wall went up in divided Germany, Klaus Richter, now prosperous, now raising three children on his own successful farm, joined protests against it. He gave speeches about freedom, about democracy, about the American soldiers who had taught him what those words truly meant by showing mercy when they could have shown vengeance.

“I learned more about real freedom in 8 months as an American prisoner,” he told West German newspapers. than in 12 years under Nazi rule. The Americans showed us that strength does not come from domination. It comes from building something worth defending. Ernst Weber died in 1963 at 89 years old. His funeral was attended by all six former Luftwafa pilots he had sheltered, by a dozen former American MPs who had tracked him down over the years through military records and sheer determination, and by Lieutenant James Cooper, now a successful lawyer in Ohio,

who flew to Germany specifically to pay his respects. Cooper delivered the eulogy in fluent German, learned over 18 years of regular correspondence with Ernst. hair. Vber showed six German pilots mercy when he could have turned them in. We showed him mercy in return when we could have punished him. And from that simple exchange in a farmyard on May 8th, 1945, a friendship grew.

Not just between individuals, but between nations. Ernst Weber saved six lives that day. Those six men helped build a new Germany, a democratic Germany, an allied Germany, a peaceful Germany. His single act of courage multiplied across decades. Cooper paused, looking at the gathered crowd, German and American, young and old, united in grief for an old farmer who had chosen humanity over fear.

We are here today because Ernst Weber, at 72 years old with everything to lose, chose to see young men instead of enemies. That choice echoed across 20 years and will echo for generations more. That is not weakness. That is the kind of strength that builds alliances lasting lifetimes. Klaus Richter lived until 2008.

He was 93 when he died, surrounded by grandchildren and greatg grandandchildren who had grown up in peaceful, prosperous, democratic Germany, a Germany his generation could barely have imagined in 1945. In his final years, he gave extensive interviews to historians studying Germany’s reconstruction. He always told the same story with the same details, the same wonder in his voice.

People ask me when I stop believing in Nazi ideology, he said in a 2005 interview that would be archived by the German Historical Institute. I tell them the exact moment, May 8th, 1945, approximately 2:47 in the afternoon, when Lieutenant James Cooper handed old Ernst Weber a receipt for food given to enemy soldiers.

That is when I understood that everything I had been taught was lies and everything I had been taught to hate was actually the foundation of civilization. He leaned forward in that interview, fixing the camera with eyes that had seen the worst of humanity and the best. We expected execution. We received mercy. We expected punishment.

We received help harvesting wheat. We expected to be treated as the monsters our propaganda had made us. Instead, we were treated as men who had been lied to, which was exactly what we were. Hinrich Becker, the burned 19-year-old who had been certain he would die in a field in Bavaria, became one of Munich’s most prominent physicians.

Before he died in 2012, he established a foundation providing burn treatment to refugees and war victims regardless of nationality. The foundation’s motto engraved above its entrance came from something Corporal Davis had said to him in that barn. Healing does not ask which side you fought on. It only asks if you are human.

The story of Ernst Weber’s farm teaches us something that modern conflicts keep forgetting. Treating defeated enemies with dignity does not weaken the victor. It creates lasting alliances. It transforms former enemies into partners. It builds a peace more durable than any treaty signed under duress. The Marshall plan succeeded partly because Germans trusted American intentions.

Trust built by thousands of small mercies like Lieutenant Cooper helping harvest wheat. Like Corporal Davis treating enemy burns, like Private Rodriguez giving water to exhausted prisoners. NATO’s strength came partly because German soldiers respected American values. values demonstrated not through propaganda but through consistent action through medical care for wounded enemies, through fair treatment of prisoners, through seen humanity even in those who had fought against you.

Klaus Richtor wrote in his memoir published in 1987 and now required reading in German schools. We lost the war on battlefields from Normandy to Berlin. But America won the peace in places like Ernst Weber’s farm where mercy met mercy and enemies discovered they had been lied to about each other. They won it in P camps where German soldiers were fed the same rations as American soldiers.

They won it in field hospitals where German wounded received the same treatment as American wounded. They won it in a thousand small moments of unexpected humanity that added up to a friendship that has lasted 80 years. In 2025, eight decades after Ernst Weber hid six Luftwaffa pilots in his barn and American MPs helped bring in his harvest, Germany and America remain close allies.

Former enemies are now partners in NATO, in trade, in democratic values, in facing new challenges together. That alliance began with strategic decisions by leaders like Eisenhower and Marshall who understood long-term thinking. But it was built by men like Lieutenant James Cooper, Corporal Davis, and Private Rodriguez, who understood that wars create ruins, but mercy builds nations.

And it was tested by men like Ernst Weber who showed humanity when he could have shown fear and Klaus Richter who recognized truth when he saw it practiced instead of just preached. Ernst Vber expected execution in his farmyard on May 8th 1945. He found humanity instead. Klaus Richtor expected vengeance from his capttors.

He found mercy, medical care, coffee, and help harvesting wheat from that single afternoon. Enemy pilots working alongside enemy soldiers to save an old man’s crops began a friendship that outlasted the war by eight decades and counting. The wheat harvested in Ernst Weber’s field that day became seeds of peace that fed nations for generations.

That is not weakness. That is the kind of strength that changes the world. The generation that fought World War II is disappearing. Every day we lose more voices, more stories, more lessons about humanity in the darkest times. If your father, grandfather, or grandmother served in World War II on any side, in any capacity, share their story in the comments below.

These memories are precious. They remind us that even in total war, individuals made choices that mattered. They remind us that mercy is stronger than vengeance, that friendship is more powerful than conquest, and that the true measure of victory is what kind of peace you build afterward. Next week, the Japanese kamicazi pilot who refused his mission and the American admiral who made him a chef on an aircraft carrier.

Another story of unexpected humanity that changed everything. Subscribe so you do not miss it. These stories need to be remembered.