They were told the American prison camps would be brutal. But when 11 German women prisoners stepped off a military transport bus into the suffocating heat of Florida in August 1945, they never imagined they would face something far worse than barbed wire and guard towers. A wrong turn, a flooded road, a desperate driver trying to find another route through the vast, mysterious wetlands called the Everglades. Then the bus lurched.

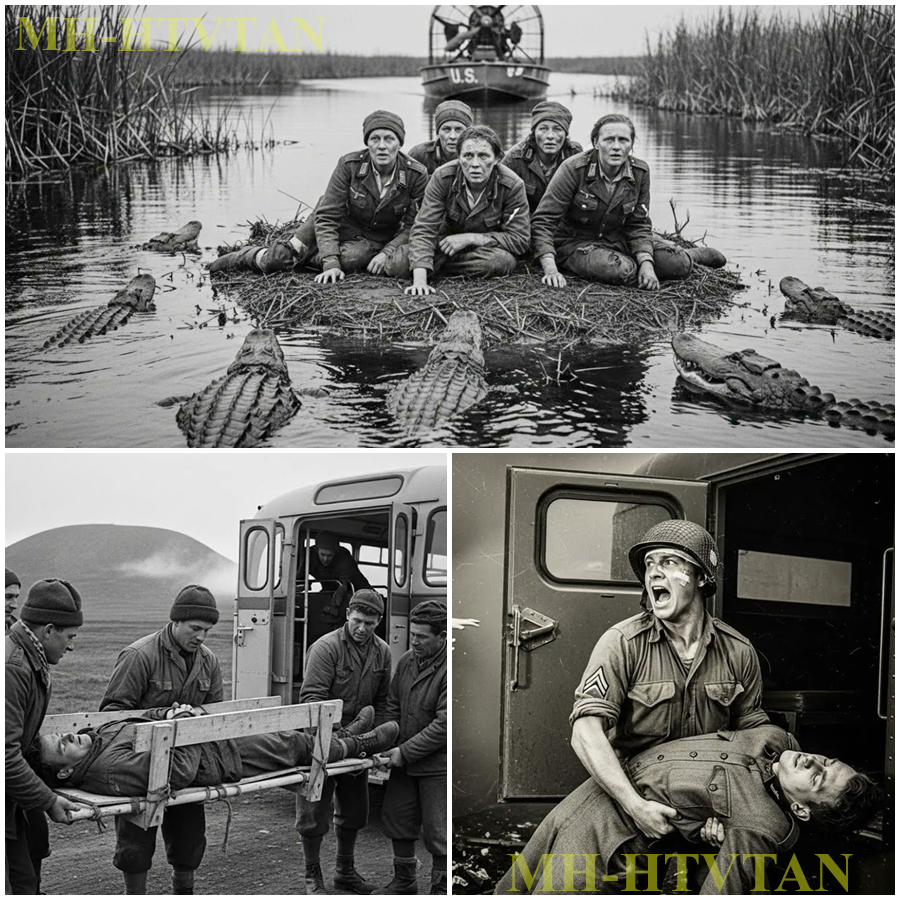

Metal screamed and cold swamp water rushed in through broken windows. Nine days later, search crews found them huddled on a patch of mud barely 6 feet across. Surrounded by dark water and the yellow eyes of alligators. They had survived not on military training or propaganda, but on something far more fragile. Hope.

The summer of 1945 was a strange time to be a German prisoner of war in America. The war in Europe had ended in May. Hitler was dead. The Reich had crumbled into dust and rubble.

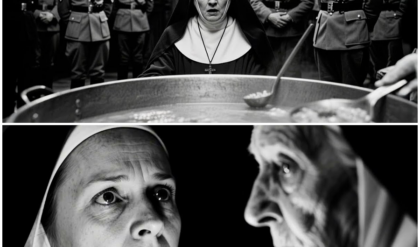

Yet thousands of German prisoners remained scattered across the United States, held in camps from Texas to Michigan, waiting for ships to take them home to a country that no longer existed as they remembered it. Among these prisoners were women, not soldiers exactly, but auxiliaries. The Vermach had called them helper inan helpers.

They had been radio operators, clerks, nurses, telephone switchboard operators, young women who had worn grey green uniforms, and served the German military machine in roles that freed men to fight. When Germany fell, these women were captured alongside the soldiers. The Americans did not quite know what to do with them. In early August, 11 such women were loaded onto a military bus in Georgia.

They had been held at a temporary detention facility near Savannah, sleeping in converted barracks that still smelled of pine tar and mildew. Now they were being moved. The guards told them they were going to a proper P camp in southern Florida, a place with real fences, proper bunks, and kitchens that served hot meals. The women accepted this news with weary silence.

They had learned not to ask too many questions. They had learned that compliance was survival. The bus was an old military transport painted olive green with hard wooden benches and windows covered by metal mesh. Two American guards sat up front, one driving, one riding shotgun with a rifle across his lap.

The 11 women sat in back, their small bags of possessions clutched on their laps. They ranged in age from 19 to 34. Some had been pretty once before years of war had hollowed their cheeks and dulled their eyes. Now they just looked tired. Among them was Greta, 26, a former telephone operator from Hamburg.

She sat near the back, staring out through the mesh at the passing landscape. The American South was nothing like Germany. Everything was bigger, greener, wilder. The trees dripped with strange gray moss. The heat was crushing, even with the windows open. Sweat soaked through her thin cotton shirt within minutes. Beside her sat Leisel, just 19, who had been a clerk in the Luftvafa offices in Berlin.

She twisted a handkerchief in her lap over and over. A nervous habit she could not break. The bus rumbled south through Georgia, then crossed into Florida. The landscape changed. Pine forests gave way to flat scrubland, then to marshes that stretched endlessly on both sides of the narrow highway. Water gleamed between the trees.

Birds with long legs and curved beaks stood motionless in the shallows. The air grew thicker, heavier, harder to breathe. The women fanned themselves with their hands, but it did nothing. The heat was inescapable. The driver, a corporal named Jenkins, had been given a map and simple directions. Follow Highway 41 south to Miami, then east to the camp. Easy enough.

But Jenkins had only been in Florida for 3 weeks. transferred from a desk job in Virginia. He did not know the roads. He did not know that summer floods could turn highways into rivers overnight. He did not know that one wrong turn could mean the difference between civilization and wilderness. It happened just before sunset.

They had been driving for nearly 8 hours with only one stop for the women to use a makeshift latrine behind a gas station. Jenkins was tired. His eyes burned from the glare off the wet road. When he saw the detour sign, handpainted and leaning at an angle, he followed it without question. Road closed ahead. Detour right.

The paved highway gave way to a dirt road. Then the dirt road became gravel. Then the gravel became mud. Jenkins slowed down, gripping the wheel tighter. The other guard, Private Kowalsski, leaned forward, squinting through the windshield. “This does not look right,” he muttered. Jenkins ignored him. The map showed a secondary route through this area. He was sure they could find it.

The bus pushed deeper into the wetlands. On both sides, water stretched away into the gathering darkness. Cypress trees rose like skeletal fingers from the swamp. Spanish moss hung in gray curtains. The road, if it could still be called a road, was now just two muddy ruts winding through the marsh.

Water sloshed over the hubs of the wheels. The engine groaned in the back. The women had grown silent. They could feel the bus struggling. They could see the water rising outside. Greta pressed her face to the mesh window and saw only darkness and water. “Where are they taking us?” Leisel whispered. Greta did not answer because she did not know. Then the bus lurched violently to the left. Jenkins shouted.

The front wheels dropped into a hidden ditch, a wash out carved by recent floods. The bus tilted at a sickening angle. Metal screamed as the frame twisted. Then the whole vehicle tipped over onto its side with a tremendous crash. Everything became chaos. The women were thrown against the walls, against each other, into a tangled heap of bodies and bags and screaming.

The windows shattered. Cold swamp water rushed in through the broken glass, black and stinking of rot. The bus settled with a groan, half submerged, the roof now sideways, the floor a wall. Greta found herself underwater for a moment, her lungs screaming.

She kicked toward what she thought was up and broke the surface, gasping around her. Other women were struggling, coughing, crying out in German and broken English. Someone was bleeding. Someone else was trapped under a bench. The water was rising fast, pouring in through every gap and crack. Up front, Jenkins was unconscious, his head bleeding where it had struck the steering wheel.

Kowalsski was awake, but dazed, his rifle lost somewhere in the dark water. He grabbed Jenkins by the collar and dragged him toward the back, toward the women, toward the only way out, the rear emergency door, now above them like a hatch. “Get out!” Kowalsski shouted, his voice ragged. Everybody out now. He pushed one woman toward the door, then another. They climbed desperately, pulling each other up, scrambling through the opening into the night.

One by one, they tumbled out onto the side of the bus, which was now partially above water, a small metal island in the swamp. The last one out was Leisel. She was crying, shaking, her hands cut from broken glass. Greta grabbed her and pulled her close. All 11 women huddled together on the overturned bus, soaking wet, bleeding, terrified.

Kowalsski climbed out last, still trying to wake Jenkins. The corporal groaned, but did not open his eyes. They looked around. Darkness had fallen completely. The sky above was deep purple, scattered with stars that gave almost no light. Around them, the Everglades stretched in every direction. An endless maze of water and grass and trees.

There was no road visible anymore. No lights, no sounds except the hum of insects and the distant splash of something large moving through the water. They spent the first night on top of the bus. There was nowhere else to go. The water around them was dark and full of unknown dangers. Kowalsski tried to get his bearings, but the darkness was absolute. He had lost his flashlight in the crash.

His rifle was gone. All he had was a pocketk knife and a waterlogged map that was useless now. The women shivered despite the heat. Their clothes were soaked. Some had lost their shoes in the crash. They huddled together for comfort, speaking in low voices, trying to understand what had happened.

Greta took charge without really meaning to. She had been a supervisor in the telephone exchange, used to managing people in crisis. She checked everyone for injuries. Two women had cuts that needed bandaging. One, a woman named Helga, had twisted her ankle badly. Jenkins remained unconscious, his breathing shallow. What do we do? Leisel whispered.

Greta did not answer right away. She was thinking. They were lost in a swamp. No one knew exactly where they were. This detour sign had led them miles off course. It could be days before anyone found them or longer. Kowalsski tried to sound confident. We stay put, he said. Search parties will come. They know our route. They will find us. But even as he spoke, doubt crept into his voice.

He did not know how far off course they had gone. He did not know if anyone had seen them turn off the highway. The night was alive with sounds. Frogs croaked in deafening chorus. Insects buzzed and bit. Something splashed nearby. Then again closer. One of the women screamed softly. What was that? Alligators? Kowalsski said quietly. Stay still.

Do not go in the water. The word hung in the air like a curse. Alligators. None of the German women had ever seen an alligator. They had only heard stories. Terrifying American stories about giant reptiles with jaws that could crush bones. Greta stared into the darkness. She could see nothing, but she felt watched. The swamp was not empty.

It was full of life, ancient and patient and hungry. She thought of home, of Hamburg before the bombs, of clean streets and electric lights and safety. That world felt impossibly distant now, like something from another life. Here she was just prey. Dawn came slowly, the sky turning from black to gray to pale orange.

With light came clarity and horror, the bus was tilted in murky brown water that stretched in every direction. The road they had been following was completely submerged. Around them, cypress trees rose from the water like ancient monuments. Lily pads floated on the surface. Birds began to call, sharp and strange. And there floating about 30 feet away was an alligator.

It was massive, perhaps 12 feet long, its riged back breaking the surface like a log. But logs did not have eyes. The creature watched them with cold intelligence. One of the women whimpered. Kowalsski moved slowly, positioning himself between the group and the alligator. Nobody move, he whispered. It was unnecessary advice. Everyone was frozen.

After several minutes, the alligator submerged and disappeared, but they all knew it was still there and probably not alone. Kowalsski made a decision. We cannot stay on the bus, he said. It is too exposed. We need solid ground. He pointed to a small hummock visible about 100 yards away through the trees. A raised patch of earth covered in grass and scrub. It looked tiny, but it was above water. It was land.

Getting there would mean entering the water. The thought terrified everyone. But staying on the bus meant roasting under the sun with no shade, no food, no fresh water. Greta looked at the other women. We have to try, she said. We cannot wait here. One by one, they agreed. They prepared as best they could. They tore strips from their clothing to make bandages for the wounded.

They fashioned a crude stretcher for Jenkins from broken seat planks and uniform jackets. They took what little they could salvage from the bus, a canteen, a first aid kit, a pocket Bible, a few personal items. Then, with Kowalsski leading, they slipped into the water. The water was warm and thick, reaching chest high on most of the women. The bottom was soft mud that sucked at their feet.

Every step was an effort. Every splash sounded impossibly loud. Greta held Leisel’s hand, keeping the younger woman close. Behind them, two women carried Jenkins on the makeshift stretcher, struggling to keep his head above water. Helga limped on her injured ankle, biting her lip against the pain. Halfway to the island, something brushed against Greta’s leg.

She gasped, stumbling, pulling Leisel with her, but it was only a fish or a branch or nothing. She kept moving. They all kept moving. To stop was to think. To think was to panic. It took 20 minutes to reach the hummock. When they finally climbed onto the muddy bank, collapsing onto solid ground, several women wept with relief.

The island was small, perhaps 6 feet across at its widest point, surrounded by sawrass and water. A single stunted cypress tree provided minimal shade. It was not much, but it was land. It was survival. By the third day, hope was fading. No search planes had flown overhead. No boats had come through the channels. They were alone in the vast Everglades. 13 people on a patch of mud barely big enough to hold them all.

The heat was unbearable. The sun beat down without mercy, turning the island into an oven. There was no escape from it. Water became the most pressing need. The swamp water around them was undrinkable, brackish, and full of bacteria. Kowalsski had managed to save one canteen from the bus, but it held less than a quart.

12 people sharing one quart of water under a Florida sun. It was gone by the end of the first day on the island. They tried to collect dew in the mornings, using pieces of cloth to soak up moisture from the grass and ring it into their mouths. It was not enough. Thirst became a constant torture.

Worse than hunger, worse than the insects, worse than the fear. Their lips cracked, their tongues swelled. Some of the women became delirious, muttering in German about childhood memories, about ice cream and cold beer and snow. Food was scarce, too. Kowalsski tried to catch fish with a hook fashioned from a safety pin and line from unraveled shoelaces.

He caught nothing. The fish in the Everglades were too smart, or he was too clumsy. They had no bait anyway. They tried eating grass, but it made them sick. They found a few berries on a low bush, but no one knew if they were poisonous. They ate them anyway. Desperation made decisions. The alligators remained a constant presence. They did not attack, but they watched.

Sometimes two or three would float near the island. Their eyes like yellow marbles just above the waterline. The women learned to recognize them, gave them names whispered in bitter humor. That one is Hans. That one is Adolf. Dark jokes to fend off darker thoughts. On the fourth night, Jenkins finally woke. He was weak, confused.

His head wound infected and oozing. He did not remember the crash. He did not know where he was. Kowalsski tried to explain, but Jenkins just stared at him blankly before slipping back into unconsciousness. They had nothing to treat his wound properly. The first aid kit held only a few bandages and some iodine already used up on other injuries.

By the fifth day, the group was fracturing. Exhaustion, thirst, and fear had worn away the thin veneer of cooperation. Arguments broke out over nothing. Who got to sit in the small patch of shade? Who was drinking more than their share of the pitiful morning dew? Whether they should stay on the island or try to walk out through the swamp. Kowalsski insisted they stay put.

“This is where the search parties will find us,” he said, though his voice lacked conviction. “If we wander off, we will just get more lost.” But another woman, a former nurse named Breijgit, disagreed. We are dying here, she said slowly. We must try to find help. We must move. The debate grew heated. Voices rose.

Some of the women sided with Kowalsski, too weak to imagine walking through the swamp again. Others agreed with Breijit, willing to risk anything rather than sit and wait for death. Greta tried to mediate, but she was exhausted too, her authority crumbling. In the end, they stayed, not because they agreed, but because no one had the strength to leave. The sixth day was the worst.

The sun seemed hotter than ever. One of the women, a young clerk named Anna, collapsed midm morning and did not wake up. They thought she was dead at first, but she was still breathing, barely. Her pulse weak and thready, heat stroke, dehydration. There was nothing they could do but move her into the tiny patch of shade and wet her lips with dew.

That afternoon, they heard an airplane. It was distant, a low droning that grew louder, then faded. They screamed. They waved their arms. They tore off pieces of their light colored clothing and waved them like flags, but the plane never appeared. It was flying too high or too far away. It passed over the endless green swamp without seeing them.

When the sound finally disappeared completely, several women broke down sobbing. That night, Leisel curled up next to Greta and whispered, “I do not want to die here. Not like this. Not in this horrible place.” Greta held her and said nothing because there was nothing to say. They might all die here on this six-foot island in this swamp so far from home. The seventh day brought rain. It came in the late afternoon.

a sudden storm that rolled across the Everglades with thunder and lightning and sheets of water. They were terrified at first, huddling together as the wind whipped the cypress tree and lightning struck close enough to smell, but then they realized rain meant water, fresh water. They tilted their heads back and opened their mouths. They spread out what was left of their clothes to catch the rain.

They cuped their hands and drank and drank until their stomachs hurt. It was the most beautiful thing any of them had ever tasted. Cold, clean, life. The storm lasted perhaps 20 minutes, but it was enough. They managed to collect nearly a quart of rain water in a piece of torn uniform. They rationed it carefully, knowing it might be days before it rained again.

The rain also revived Anna, who came to coughing and confused, but alive. It was a small miracle, and it gave them hope. That evening, as the sky cleared and the stars came out, Greta sat at the edge of the island and stared at the water. The alligators were still there, floating like ghosts in the twilight. She wondered if they were waiting for the humans to weaken enough to become prey. She wondered how much longer they could survive.

Seven days felt like an eternity, but they were still alive, still together, still fighting. On the eighth day, something shifted. It was subtle, hard to define, but everyone felt it. Perhaps it was exhaustion stripping away pretense. Perhaps it was proximity, forcing honesty.

Perhaps it was simply that they had survived together this long and realized they were no longer prisoners and guards. They were just people trying not to die. Kowalsski stopped giving orders and started asking questions. Do you think we should try to signal again? What if we build a raft? The women responded not as subordinates, but as equals. Greta, in particular, found herself speaking up more. She had ideas.

She had experience managing crisis. Her opinions mattered here not because of rank or nationality, but because they were sensible. They shared stories to pass the time. Kowalsski talked about his family in Pennsylvania, his father who worked in a steel mill. His mother who made the best pureogi he had ever tasted.

Breit talked about nursing school in Munich, about dreaming of becoming a doctor before the war changed everything. Leisel spoke softly about her younger brother killed on the Eastern Front and how she still expected to see him walking through the door every time she came home. The stories created connections. They were not German and American anymore.

They were people who missed their families, who had lost loved ones, who wanted to go home. The war had made them enemies, but the swamp made them survivors. That was a different kind of bond. Greta found herself thinking about what she had been taught, that Americans were the enemy, that they were ruthless, that they had no mercy. But Kowalsski had stayed with them when he could have tried to save only himself.

He had shared what little they had. He had protected them from his own fear as much as from external dangers. That did not match the propaganda. That looked like decency. Late on the eighth day, Helga’s ankle became badly infected. The swelling had spread up her leg, turning the skin red and hot to the touch.

She was feverish, shaking, slipping in and out of consciousness. Breit did what she could with the limited supplies, but it was not enough. They needed antibiotics. They needed a hospital. They needed rescue. That night, as Helga’s fever climbed, the group gathered around her. They took turns cooling her forehead with wet cloth.

They spoke to her gently in German and English, telling her to hold on, to keep fighting. Kowalsski sat with them, his hand on Helga’s shoulder, his face tight with worry. When she dies, it is on me,” he said quietly. “I got us lost. I brought us here.” Greta shook her head. “No,” she said firmly. “The detour sign was fake. Someone put it there. Maybe vandals.

Maybe just idiots. You followed orders. You did your best. We all did.” Kowalsski looked at her, surprise and gratitude in his tired eyes. She meant it. Blame was pointless here. Survival was what mattered. They kept Helga alive through the night. In the morning, her fever broke slightly. She was still desperately ill, but she was conscious. She smiled weakly at Breijit.

“Thank you,” she whispered. Breijgit squeezed her hand. “We are all in this together,” she said. “And it was true.” Nationality had ceased to matter. They were 13 people on a tiny island fighting the same fight. Sitting in the shade on the afternoon of the eighth day, Greta and Kowalsski had a conversation that would stay with both of them forever.

They were alone for a moment, the others resting or trying to fish or simply staring at the water in exhausted silence. Why did you join? Kowalsski asked suddenly. The military? I mean, why? Greta thought about it. Because I believed we were protecting Germany, she said slowly. Because I thought we were the good side. Because I was young and stupid and they made it sound like glory. She paused. I know better now.

Kowalsski nodded. I joined because my dad said it was my duty. Because I did not want to look like a coward. Because I did not know what else to do. He looked at his hands. I never shot anyone, you know. I worked in supply, counted boxes, filled out forms. That is my war story. Pretty pathetic. It is not pathetic. Greta said, “You are here.

You are trying to keep us alive. That matters more than any battle.” Kowalsski looked at her. Really looked. And she saw something shift in his expression. Recognition, respect, maybe even friendship. They sat in silence for a while. Then Kowalsski said, “If we get out of this, I am going to recommend you for a commendation.

” Greta laughed, a dry sound. “I am a prisoner of war,” she said. “You cannot commend a prisoner,” he shrugged. “Then I will write a letter. Tell them what you did. How you held everyone together. Someone should know.” Greta did not respond, but tears pricked her eyes. She turned away so he would not see.

For years, she had been an enemy, a threat, a problem to be managed. Here in this terrible place, someone saw her as a person. That mattered. That mattered more than she could say. The ninth day dawned clear and brutally hot. They had been on the island for a week. Jenkins was barely clinging to life, his infection raging. Anna was weak, but stable. Helga’s leg was worse.

Two other women had developed dysentery from the contaminated water they had been forced to drink in desperation. They were all at the breaking point. Greta knew they could not last much longer. Another day, maybe two at most. After that, people would start dying. They had to do something. She gathered the group and proposed a plan. We build a raft, she said. A small one. Kowalsski and I will try to find help. The rest of you stay here.

If we find a way out, we will send rescue. If not, she did not finish the sentence. She did not need to. It was a terrible plan. The raft would be crude, barely functional. The swamp was vast and dangerous. They could easily get lost worse than they already were. But it was better than waiting to die. Kowalsski agreed immediately.

The women helped them gather materials, branches, vines, pieces of clothing to bind it together. By midm morning, they had something that might float barely. Just as Greta and Kowalsski were preparing to launch the raft, Leisel suddenly stood up. “Listen,” she said. Everyone froze. In the distance, barely audible over the hum of insects, was a new sound.

A mechanical wine. An engine. No, multiple engines growing louder. The sound grew steadily louder until it was unmistakable. Airboats, the distinctive roar of giant propellers pushing flatbottomed boats through shallow water. The rescue they had prayed for. The miracle they had almost stopped believing in. They screamed. They waved.

They splashed into the water at the edge of the island, shouting in German and English and pure, desperate hope. Two airboats emerged from the cypress trees, cutting through the saw grass and clouds of spray. US Coast Guard markings on the sides, men in uniform standing at the controls. The boats slowed as they approached the island, their engines dropping to an idol.

One of the guardsmen stared at the ragged group in disbelief. “Jesus Christ,” he said. “You are the missing transport. We have been searching for 9 days.” The guardsmen moved quickly. They pulled the weakest aboard first, Jenkins, Anna, Helga, then the others, one by one, until all 13 were on the boats. Greta was one of the last to leave the island.

She looked back at the tiny patch of mud that had been their home, their prison, their salvation, 6 feet of earth that had kept them alive. She would never forget it. As the airboats roared to life and began the journey back to civilization, Greta sat next to Kowalsski. Both of them were shaking. Not from cold or fear, but from relief so overwhelming it felt like a physical force. We made it, Kowalsski said, his voice cracking.

We actually made it. Greta nodded, unable to speak. Leisel was crying, her face buried in Greta’s shoulder. Around them, the other women wept or laughed or just stared in stunned silence. The airboats cut through the Everglades, following channels the survivors had never known existed. In less than an hour, they reached a dock where ambulances and military vehicles waited.

Medical personnel rushed forward with stretchers, water, blankets. The media was there, too. Cameras flashing, reporters shouting questions that no one could answer. As they were being loaded into ambulances, one of the Coast Guard officers approached Kowalsski. Sir, we need to debrief you, figure out what happened. But Kowalsski shook his head.

Later, he said, “Right now, these people need medical attention. All of them.” The officer nodded and stepped back. At the hospital in Miami, they were separated for treatment. Greta was put in a bed with clean white sheets, given IV fluids, examined by doctors who marveled that she was alive. “You were severely dehydrated,” one doctor said.

Another day or two and you might not have made it. Greta just nodded. She knew. That night, lying in the hospital bed, Greta thought about everything that had happened. Nine days in the Everglades, nine days on a six-foot island, nine days of heat and thirst and alligators circling, but also nine days of seeing people at their best and worst. Nine days of breaking down barriers she had not even known existed.

She had entered that swamp as a prisoner of war. She emerged as something else, a survivor, a human being who had been treated with dignity by her enemy when it mattered most. All 13 survivors recovered, though some took longer than others.

Jenkins spent three weeks in the hospital with his head injury and infection. Helga needed surgery on her leg and months of physical therapy. Anna battled complications from heat stroke for weeks, but they all lived against the odds in a place that should have killed them. They all survived. The women were transferred to the proper P camp once they were medically cleared.

It was exactly as described. Clean barracks, regular meals, work assignments that were manageable. But after the Everglades, it felt like luxury. Hot showers were a revelation. Three meals a day seemed impossibly abundant. The simple fact of being safe, of not having to watch for alligators or ration drops of water, was overwhelming.

Greta and the other women were treated as minor celebrities by the other prisoners. Everyone wanted to hear the story. How did you survive? Were you scared? What about the alligators? Greta told the story many times, but always she left out certain details. The moments of doubt, the times she thought they would all die. The way Kowalsski had become more than a guard had become a friend.

Those parts felt too private, too complicated to share. 3 weeks after the rescue, Kowalsski visited the camp. He was not on official business. He had asked for permission to see the women to check on their recovery. The camp commander was hesitant, but eventually agreed.

Kowalsski sat in a visiting room with Greta, a table between them, a guard watching from the corner. I kept my promise, Kowalsski said. He slid a piece of paper across the table. It was a letter, official US Army letterhead, addressed to the War Department. In it, Kowalsski described the ordeal in detail and specifically praised Greta’s leadership, her courage, her humanity.

He recommended that her conduct be noted in her record and that she be considered for early repatriation due to exceptional behavior. Greta read it twice, not believing what she was seeing. Why? She asked. Why would you do this for me? Kowalsski looked uncomfortable. Because it is true, he said. Because you saved lives out there, mine included.

Because you deserve recognition. Enemy or not? Greta felt tears welling up. “Thank you,” she whispered. “You did not have to.” “I know,” he said. “But I wanted to. They talked for another hour. Not about the war or politics or nations, but about life.” Kowalsski talked about going home to Pennsylvania, about maybe using his GI Bill to go to college, something his father never dreamed of.

Greta talked about returning to Germany, about trying to find her family in the ruins of Hamburg, about hoping to rebuild. They were tentative dreams, fragile hopes, but they were real. When it was time to leave, they shook hands awkwardly. “Take care of yourself,” Kowalsski said. “You, too,” Greta replied. They both knew they would probably never see each other again. Their worlds were too different.

The gulf between prisoner and guard too wide for normal circumstances. But the Everglades had not been normal circumstances. And what they had shared there would last forever. In the spring of 1946, Greta and the other women were finally repatriated. They boarded a ship in New York Harbor, bound for Bremer Haven, Germany. The voyage was nothing like the terrified journey to America 18 months earlier.

This time they were going home. But home was a complicated concept. The Germany they returned to was devastated. Cities were rubble. Millions were homeless. Food was scarce. The future was uncertain. Greta found her mother alive, but barely. Her father had died in the final months of the war.

Her brother was missing, presumably dead on the Eastern Front. Their home in Hamburgg was gone, bombed flat in 1943. They lived in a basement apartment now, sharing space with two other families. Her mother wept when she saw Greta, holding her like she would never let go. The adjustment was hard. Greta had survived the Everglades.

But coming home to a destroyed nation felt like a different kind of survival challenge. Yet, she carried something with her from those nine days. A perspective, a memory of moments when nationality did not matter. When humanity was the only thing that counted, when an American guard treated her like a person worth saving, she kept the letter Kowalsski had written, hidden carefully among her few possessions. Sometimes on hard days, she would take it out and read it.

Not because she needed the validation, but because it reminded her of something important. that even in the darkest circumstances, even when divided by war and ideology and fear, people could choose decency. That was worth remembering, that was worth protecting. Greta lived a long life.

She married, had children, rebuilt a career as an administrator. She rarely spoke about the war. It was too painful, too complicated. But she did tell her children about the Everglades, about the nine days on the six-foot island, about the alligators circling and the heat and the thirst. About the American soldier who became a friend.

Her daughter asked once, “Were you scared?” Greta thought about it, terrified, she said, “Every moment, but also strangely, I felt more alive than I ever had before or since. When you are that close to death, everything becomes very simple. You realize what matters and what does not. People matter. Kindness matters. Everything else is just noise.

In 1982, Greta received a letter from America. It was from Kowalsski’s daughter. Her father had passed away, and while going through his papers, she had found notes about the Everglades incident. She wanted to know if Greta was the same person. if she remembered, if she was still alive. Greta wrote back immediately.

She shared her memories, her gratitude, her respect for a man who had done the right thing when it would have been easier not to. They exchanged several letters after that. Two women connected by a shared piece of history, by fathers who had seen each other as human beings first and enemies second. When Greta died in 1998 at the age of 79, her children found the letter from Kowalsski among her things. It was yellowed and fragile, the paper brittle with age.

But the words were still clear, a testament to a moment when the world was at war. But two people found peace in the most unlikely place, on a six-foot island, in the middle of a swamp, surrounded by danger, but held together by humanity. And so what began as a routine prisoner transport became an ordeal that tested the limits of human endurance.

11 German women and two American guards lost in the Everglades for 9 days. Surviving on a patch of mud barely big enough to hold them all. They faced alligators, heat, thirst, infection, and despair. But they also discovered something unexpected. That in the face of death, the things that divide us become small. And the things that unite us become everything.

The soap that German women prisoners received in American camps was a shock because it represented mercy. The food was abundant because it showed prosperity. But the Everglades taught a different lesson. It taught that survival requires cooperation. That humanity transcends uniform and flag.

That sometimes the enemy is not the person across from you, but the circumstances that brought you together. Greta never forgot those nine days. Neither did any of the survivors for the rest of their lives. When asked about their war experiences, they did not talk about battles or ideology or grand historical movements. They talked about a six-foot island, about an American guard who shared his last drops of water, about German women who held each other through the darkness, about alligators that watched but did not attack.

about the moment when the airboats finally arrived and they realized they were going to live. As one of the survivors wrote years later in a memoir, “The war made us enemies. The swamp made us human.” I will take the second lesson over the first any day. That is the story worth remembering.

That in the worst circumstances, people can still choose kindness. That survival depends less on strength than on solidarity. that the things we have in common are stronger than the things that divide us. If this story moved you, if it made you think about what it means to be human in the face of impossible odds, make sure to like this video and subscribe to our channel.

We bring you true stories from World War II that go beyond the battles and the headlines to show the real people caught in extraordinary circumstances. These are stories about courage, compassion, and the surprising ways that enemies can become allies when survival depends on it. Hit that notification bell so you never miss a story. Share this with someone who appreciates true history and let us know in the comments.

What would you have done in their situation? How would you have survived? The past has so much to teach us if we are willing to listen. Until next time, remember that history is not just about nations and armies. It is about people. And people at their core are capable of remarkable things.