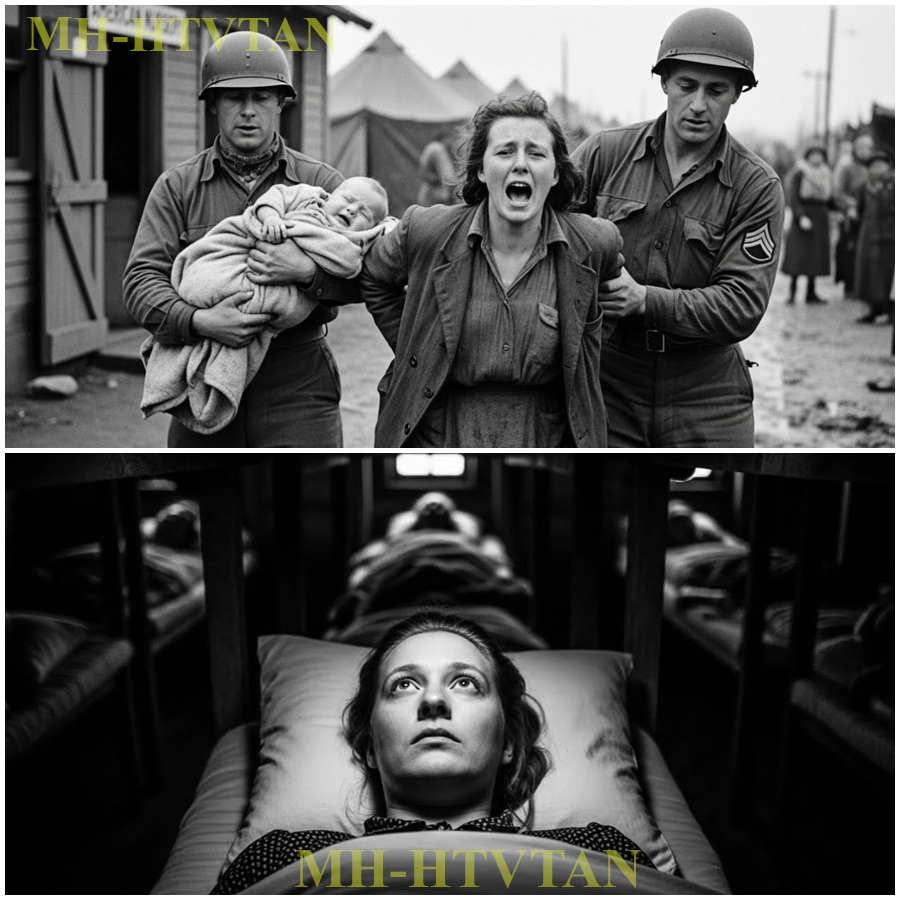

Her screams echoed through the wooden barracks as American soldiers reached for her child. Margaret clutched the bundle tighter, her arms trembling, her voice raw with terror. Nine. Nine. Please, not my baby. The other German women prisoners watched in frozen horror, remembering every propaganda warning they had ever heard about what Americans did to German children.

It was October 1945, 6 months after surrender, and 23-year-old Margaret had just given birth in a converted storage room at Camp Rustin, Louisiana. Now, as guards moved closer, speaking words she could not understand, she was certain this was the moment the enemy would take everything from her. She had survived the bombs, the trains, the ocean crossing, and childbirth in captivity.

But this, how could any mother survive this? The soldiers were gentle but firm. And as they lifted her three-day old son from her arms, Margaret collapsed to her knees, sobbing words that needed no translation. What she did not know, what none of them knew, was where they were really taking him.

6 months earlier, in the spring of 1945, Margarett had stepped off a transport train in Louisiana. Already four months pregnant and terrified, the southern heat hit her like a wall, thick and wet, so different from the cold German spring she had left behind.

The air smelled of pine trees and something sweet she could not name. Magnolia blossoms, though she would not learn that word for months. Her gray Vermachked auxiliary uniform hung loose on her thin frame, stained with sweat and dust from three days of travel across America.

She was 23 years old, unmarried and carrying the child of a Luftvafa pilot who had been killed in the final weeks of the war. Camp Rustin sprawled across red clay earth, row after row of unpainted wooden barracks surrounded by wire fencing and guard towers.

But unlike the camps she had imagined, the brutal, violent places described in Vermach briefings, this one looked almost peaceful. The paths were swept clean. Gardens grew beside some of the buildings. American soldiers walked with their rifles slung casually over their shoulders, not aimed and ready. It was all wrong.

Where was the cruelty? Where was the violence they had been promised? The first thing that struck Margaret was the smell. As the guards led the group of women past the messaul, the scent of cooking meat drifted out. Real meat, not the horse flesh or mystery scraps they had eaten in Germany. Fried chicken, biscuits, coffee. Her stomach cramped with hunger and disbelief. Behind her, another woman whispered in German, “They are trying to trick us. Food that good cannot be real.” The sounds were strange, too.

Guards called to each other in English, their voices casual, almost lazy. In the southern heat, a radio somewhere played music, American jazz, brassy and foreign. There was no shouting, no harsh commands, no boots stomping in unison. Just the ordinary sounds of a place going about its business.

Even the birds sounded different here, their calls high and unfamiliar. Margaret’s hand instinctively moved to her belly, still flat enough to hide her condition beneath the loose uniform. She had not told anyone yet. How could she? An unmarried woman, pregnant by a dead soldier, now a prisoner of the enemy. The shame of it pressed down on her shoulders almost as heavily as her fear.

What would the Americans do when they discovered her condition? Would they separate her from the others? Would they punish her child for being born German? for being born at all. As the women were lined up for processing, Margaret caught sight of her reflection in a window. She barely recognized herself. Her blonde hair was tangled and dull.

Her face was thin, making her eyes look too large, like a frightened animal. She was 23, but looked older, aged by war and fear, and the terrible uncertainty of what came next. She touched her belly again, hidden under the fabric and made a silent promise. I will keep you safe. No matter what happens, I will keep you safe.

But even as she made that promise, doubt crept in like cold water. How could she keep anyone safe? She had no power here, no rights, no protection. She was the enemy. And soon she would be a mother, alone in a foreign land, surrounded by people who had every reason to hate her. The processing station was a small building with white walls and bright electric lights, so much brighter than the dim oil lamps of Germany’s ruined cities.

An American nurse in a crisp white uniform stood behind a desk, her red lipstick impossibly bright against her pale skin. She smiled, which shocked Margaret almost as much as anything else. Why would the enemy smile? Name? The nurse asked through a translator, a German American soldier who spoke with a strange accent, mixing English sounds with German words. Margaret gave her name, her rank as a vermached auxiliary communications officer, her age.

The questions were routine, bureaucratic. Then came the physical examination. The nurse was gentle but thorough. She checked Margaret’s eyes, her teeth, her throat. She listened to her heart, and then inevitably she pressed her hand against Margaret’s abdomen. The nurse paused. Her eyes met Margarettes.

For a long moment, neither spoke. Margaret felt her heart hammer in her chest. This was it. This was when they would separate her, punish her, do something terrible to her unborn child. Instead, the nurse wrote something on her clipboard and said something in English to the translator. He turned to Margaret and said in careful German, “You will be placed in quarters with extra rations.

The doctor will see you weekly.” That was all. No judgment, no cruelty, just practical arrangements. Margaret stood there stunned, waiting for the other shoe to drop, but it never did. The messaul was loud with the sound of women eating, the clatter of metal trays and utensils echoing off the wooden walls.

Margarette joined the line, moving slowly, her mind still reeling from the medical exam. When she reached the front, a large black American man in a white apron smiled at her and ladled food onto her tray. fried chicken, golden and glistening, mashed potatoes with gravy, green beans, a thick slice of white bread with real butter, a glass of cold milk. She stared at the tray as though it held gold.

For the past year in Germany, she had eaten turnipss and watery soup, bread made with sawdust, occasionally a scrap of meat that might have been rat or horse. Once in the winter, she had gone three days eating nothing but boiled potato peels. Now in the enemy’s camp, she held more food than she had seen in months.

The chicken was still warm when she bit into it. The skin was crispy. The meat tender and juicy. Salt and spices exploded on her tongue. She had forgotten food could taste like this. Around her, other women ate in silence, some crying quietly as they chewed. One woman two tables away ate so fast she made herself sick, her body unable to handle rich food after months of starvation.

An older woman sitting across from Margaret whispered, “This is how they will kill us.” With kindness, we will become soft. Forget who we are and then they will destroy us. But Margaret could not think that far ahead. All she could think about was the baby growing inside her. Finally getting real nutrition. finally getting a chance to grow strong.

Maybe, she thought, maybe this child would not be born starving after all. The women’s barracks were simple but clean. Rows of metal bunk beds lined the walls, each with a thin mattress, two wool blankets, a pillow, and a small foot locker. It was more than most German civilians had at that moment, more than Margaret had expected.

The guards showed them the washrooms, real toilets, sinks with running water, showers that worked. There was even hot water if you knew the right time to use it. Margaret chose a lower bunk in the corner away from the door.

She had learned in the Vermach auxiliaries to always sleep where she could see both exits. Old habits died hard. She sat on the edge of her bunk and placed her hand on her belly, still hidden beneath her uniform. We are safe,” she whispered in German. “For now we are safe.” That night, lying in the darkness with 50 other women breathing around her, Margaret listened to the sounds of the Louisiana night.

Crickets sang in the grass outside. Somewhere far away, a dog barked. A guard walked past the barracks, his boots crunching on gravel, but he did not stop or look in. The normaly of it all was terrifying. She had stealed herself for violence, for cruelty, for suffering. But this quiet routine was harder to understand. She thought of her mother in Hamburg, probably dead now under the rubble.

She thought of Carl, the Luftvafa pilot who had been the baby’s father, killed in March when his plane was shot down over Holland. She thought of Germany, burning and broken. And she thought of the future, uncertain and frightening, growing inside her one day at a time. A woman in the next bunk whispered into the darkness.

In German, “Do you think they will really let us live?” No one answered. No one knew. The weeks turned into months, and Camp Rustin settled into a routine that felt almost dreamlike in its ordinariness. Each morning at 6, a bell rang. The women rose, washed, dressed, and lined up for breakfast. There was always food. Eggs, oatmeal, toast, coffee. Always enough, always hot.

The American guards counted them each morning and evening, checking names against a roster, but there was no violence in it, just bureaucracy. Margaret was assigned light duties because of her pregnancy. She worked in the camp laundry, washing and folding American uniforms, the same uniforms worn by the men who had defeated her country.

The work was hot and tiring, but not cruel. She was paid in camp script, small colored tokens that could be used at the camp canteen to buy chocolate, cigarettes, soap, even magazines and books. As her belly grew, the other women began to notice. Some were kind, sharing extra food or helping with the heavier laundry baskets. Others were cold, viewing her pregnancy as shameful, a betrayal of German morality.

To bring a child into captivity, one woman hissed. How selfish. Margaret said nothing. What could she say? That she had not planned this. That love and war did not follow rules. That her child deserved to live regardless of the circumstances of its birth. The American nurse, whose name was Dorothy, checked on Margaret weekly.

She measured her belly, listened to the baby’s heartbeat through a strange metal tube, asked questions through the translator. Are you feeling the baby move? Yes. Are you eating enough? Yes. Any pain? No. Dorothy was professional and kind, but distant. She never smiled at Margaret the way she smiled at the other nurses.

To Dorothy, Margarett was probably just another enemy woman. One more problem to manage. In July, Margarett received her first letter from Germany. It had taken three months to arrive. Passed through military sensors on both sides. certain words blacked out with heavy ink. The letter was from a cousin in Hamburgg.

The handwriting was shaky, the paper thin and cheap. Dear Margaret, it read. I hope this reaches you. I hope you are alive. Hamburg is gone. Our street is rubble. Aunt Greta died in February. Starvation, the doctor said, though there are no doctors anymore. The children beg in the streets for food. The occupation soldiers give us rations, but it is never enough.

We hear terrible things about the camps where our people are kept. Some say the Americans are kind. Some say they are cruel. I do not know what to believe. Anymore, if you can, send food. Send anything. We are starving. Margaret read the letter three times, then folded it carefully and pressed it under her pillow. That evening, she ate her dinner.

pork chops, mashed potatoes, green beans, apple pie, and felt sick with guilt. Her family was starving. Her country was in ruins. And here she sat in the enemy’s camp, growing fat and healthy. Her baby thriving inside her on American food. She tried to send a package back. Crackers, chocolate, condensed milk from the canteen, but the guards told her it was not allowed.

security reasons,” the translator said. “So all she could send was a letter full of lies about being treated well, hoping it would not make her cousin hate her, hoping it would not make her hate herself more than she already did. Not all the guards were distant.

Some, especially the younger ones, were curious about the German women, asking questions through translators, offering cigarettes, sometimes even sharing photographs from home. One guard, a farm boy from Iowa named Jimmy, seemed particularly fascinated by Margarett’s pregnancy. One afternoon, as she walked back from the laundry, her belly now large and obvious beneath her loose dress, Jimmy stopped her and said something in English.

The translator happened to be nearby. He says his sister just had a baby. He wants to know if you need anything. Margaret stared at him, suspicious. What did he want? Why was he being kind? But Jimmy just smiled, pulled something from his pocket, and held it out.

It was a small wooden rattle, crudely carved, but sanded smooth. “I made it,” the translator said for him. “For your baby,” Margarett took it slowly, her hands shaking. No one had given her anything for the baby. Not the other women, not the nurses, not anyone. And here was this American guard, this enemy soldier, offering a gift he had made with his own hands. She tried to say thank you, but the words caught in her throat.

Jimmy just nodded, smiled again, and walked away. That night, Margaret held the rattle under her blanket and cried silently. She did not understand this place. She did not understand these people. The enemy was supposed to be cruel. Instead, they were feeding her, caring for her baby, giving her gifts. It made no sense. It broke something inside her that she had been holding together since the surrender.

By September, Margaret could barely walk. Her belly was enormous. Her ankles swollen, her back constantly aching. She had been moved to lighter duties, folding laundry instead of washing it, sitting instead of standing. The baby kicked constantly now, strong thumps against her ribs that reminded her this was real. This was happening. Soon there would be another person in the world depending on her completely.

Dorothy the nurse checked her twice a week now. Any day now, she said through the translator. When the contractions start, you tell the guards immediately. We have a room prepared. Margarette nodded, but did not really understand. A room prepared. For what? For her? For the birth. It seemed too organized, too planned.

In Germany, women gave birth in basement and bomb shelters with no doctors and no medicine. Here, the Americans had a room prepared. The other women watched her with a mixture of pity and fear. Giving birth in captivity was dangerous.

What if something went wrong? What if the Americans took the baby away? What if the baby was born sick or damaged? The whispers followed Margaret everywhere. Some women still believed the propaganda that Americans did terrible things to German children, that they were experimenting on prisoners, that kindness was just a mask hiding something worse.

Margaret tried not to listen, but late at night, alone in her bunk with the baby rolling inside her, she wondered if they were right. What would happen when the baby came? Would they let her keep it? Would they take it away to some American orphanage? The not knowing was worse than any actual cruelty could be. Late one night in September, unable to sleep with the baby pressing against her lungs, Margaret sat outside the barracks on the wooden steps. It was against the rules to be outside after lights out.

But the guards seemed to understand that pregnant women needed air and space. The Louisiana night was thick with humidity, the air heavy with the smell of honeysuckle and pine. She thought about her life before the war. She had been a student studying literature in Berlin, dreaming of becoming a teacher. Then the war had swallowed everything.

She had joined the Vermach auxiliaries because everyone did, because it was expected, because refusing meant suspicion and danger. She had manned radio communications, passing messages she did not understand, part of a machine she could not see. She had believed at first in the things they told her, that Germany was strong, that the furer was leading them to glory, that the enemies were monsters who would destroy the German people if given the chance. She had believed it because everyone around her believed it, because questioning meant danger, because it was

easier to believe than to doubt. But now sitting in the American night, 7 months pregnant with enough food in her belly to keep her and the baby healthy, she could not hold on to those beliefs anymore. The Americans were not monsters. They were just people. Young men who missed their families, nurses who did their jobs, officers who followed rules.

They were not trying to destroy her. They were just trying to manage the aftermath of a war they had won. The realization was painful, like pulling out a splinter that had been embedded too long. If the Americans were not monsters, then what did that mean about everything she had believed? What did it mean about the war? What did it mean about her own country which had sent millions to die for a lie? The women argued about it sometimes late at night in the barracks when the guards could not hear. Some clung to the old beliefs, insisting that American

kindness was a trap, that the real cruelty would come eventually. Others, especially the younger ones, had begun to accept the reality in front of them. “We lost,” one girl said simply. “We lost and they won. And they are better at being human than we were told.

” An older woman, a former Nazi party member, slapped the girl across the face. Never say that. Never. We did not lose because they were better. We lost because we were betrayed. But even as she said it, her voice lacked conviction. They had all seen too much. The food, the medicine, the clean water, the absence of cruelty. It was hard to maintain hatred in the face of consistent decency. Margaret stayed out of these arguments.

She had her own battles to fight inside her own heart. Some days she felt like a traitor for accepting American food, for being grateful for their care. Other days she felt angry that her own country had never cared for its people the way these supposed enemies did. The conflict exhausted her almost as much as the pregnancy.

One afternoon in early October, as Margaret sat in the shade outside the laundry building, too pregnant now to work, just waiting. always waiting. She watched a group of American soldiers playing baseball in a field nearby. They were young, maybe 18 or 19, laughing and shouting and running in the sun.

They looked so carefree, so unbroken by war. A few German women stood at the fence watching them, and one said bitterly, “They do not know what war is.” They came here at the end and claimed victory. But Margaret thought differently. Maybe that was the point. Maybe America was strong, not because it was cruel, but because it had been able to protect its own people.

Its cities were not bombed. Its children were not starving. Its young men could still laugh and play baseball. Germany had promised strength through sacrifice, glory through suffering. And where had it led? To rubble, to starvation, to defeat.

America had promised nothing to Margaret, but it had given her and her unborn child a chance to survive. That seemed like the greater power. She thought about what she would tell her child someday when he or she was old enough to understand. Would she tell the truth? That the enemy had been kinder than their own people? That the Americans had shown more mercy than the Reich had ever shown to anyone? Or would she lie? let her child grow up believing the comfortable myths that made defeat easier to bear. She did not know.

She did not know anything anymore except that the baby would come soon and nothing would ever be the same again. 3 days before the birth, Margaret woke in the middle of the night with cramping pain. She lay in her bunk, breathing through it, trying not to wake the other women.

But the pain got worse, sharper, and finally she had to call out, “Help!” Bit a help. Within minutes, guards came with flashlights. Dorothy the nurse arrived, still in her night gown with a coat thrown over it. She examined Margaret quickly and shook her head. “False labor,” the translator said. “Not the real thing yet. Soon, though.

” They gave Margaret water and helped her back to bed, and Dorothy sat with her for an hour, holding her hand while the false contractions slowly faded. It was such a simple act of kindness, sitting with a frightened woman in the dark. But it meant everything to Margaret. Dorothy did not have to do that.

She could have left once she determined it was false labor, but she stayed. this American nurse, this woman who had every reason to hate Germans, stayed and held the hand of an enemy prisoner having a baby in captivity. When Dorothy finally left, Margarette lay awake until dawn, thinking about all the small kindnesses she had received in this place, the guard who had carved the rattle, the cook who always gave her extra milk, the other prisoners who had helped with her work, even Dorothy sitting with her in the dark. None of it made sense with what she had been taught. And all of it

was undeniably real. The real labor started on October 12th, 1945 at 3:00 in the morning. Margarette woke with a sensation like her body was being torn in half. She tried to stay quiet, but the pain was too intense. She cried out, and immediately the barracks came alive. Women rushed to her bunk. Guards were called. Dorothy appeared within minutes.

Now all business and efficiency. It is time, the translator said. Two guards brought a stretcher. They lifted Margaret onto it with surprising gentleness and carried her out into the warm Louisiana night. The stars were brilliant overhead. The Milky Way stretched across the sky like spilled milk.

Margaret stared up at them as another contraction seized her and she thought, “This is how my child enters the world under foreign stars in enemy hands.” They carried her to a small building near the infirmary. Inside was a clean room with white walls, a bed with white sheets, bright lights, and medical equipment. It looked like a hospital, not a prison. Dorothy was there, and another nurse and a doctor.

an older man with gray hair and kind eyes who spoke no German, but smiled at Margaret with professional reassurance. The labor lasted seven hours. Seven hours of pain that made Margaret forget everything except the primal work of bringing life into the world. Dorothy coached her through it, holding her hand, wiping her forehead with cool cloths, speaking in English words that Margaret could not understand, but whose tone was clear. You can do this.

You are strong. Almost there. And then, as the sun rose outside the window, turning the sky pink and gold, Margaret felt the final push, felt something give way. Heard the doctor saying something urgent in English. And then a cry high and thin and perfect. A baby’s cry. Her baby’s cry.

“A boy,” Dorothy said through the translator. And then she was placing him on Margarett’s chest, still wet and wrinkled and impossibly small. Margarett’s arms came up automatically, cradling him, and she looked down into his scrunched red face, and felt her heart crack open in a way she had not known was possible. He was perfect. 10 fingers, 10 toes, a shock of dark hair, tiny hands that waved in the air as if reaching for something. He was alive and healthy and real.

Despite everything, the war, the defeat, the captivity, the fear, this child had survived. This child was here. Margaret wept, holding him against her chest, feeling his warmth, his tiny heartbeat against hers. For the first time in years, she felt something pure and uncomplicated. Love.

Simple, overwhelming, unconditional love. This child was German and American soil would be the first earth his eyes ever saw. But none of that mattered. He was hers. He was alive. That was all that mattered. For 3 days, Margarett was allowed to stay in the recovery room with her baby. They brought her extra food, soup, bread, fruit, milk.

They gave her clean gowns and fresh sheets. Dorothy checked on her regularly, showing her how to nurse, how to change diapers, how to swaddle the baby, so he felt secure. It was almost like being in a real hospital, not a prison camp. The other women came to visit, slipping in during work breaks to see the baby.

Some couped over him, delighted by his tiny perfection. Others looked at him with sadness, thinking of children they had left behind in Germany, or children who had died in the bombing, or children they would never have. But all of them agreed. He was beautiful. Margaret named him Klouse after her father who had died in the first year of the war.

Klaus Wolf Gang, the middle name for the Luftvafa pilot who had been his father. The translator wrote it down in the camp records, making it official. Klaus Wulf Gang, born October 12th, 1945, Camp Rustin, Louisiana, German citizen, prisoner of war. But on the evening of the third day, as Margaret nursed Klouse in the fading light, Dorothy came in with two guards.

The translator was with them. Margarett’s blood went cold. This was it. This was the moment she had been dreading. They were going to take him away. Dorothy said something in English. The translator hesitated, then spoke. We need to take the baby to the nursery for the night. You need to rest and recover. Margaret pulled Klouse tighter against her chest. No. Nine. He stays with me.

The translator spoke again. His voice gentle but firm. It is for his health. The nursery has proper equipment, proper heat. You are still weak from the birth. We will bring him back in the morning for feeding. No. Margarett’s voice rose to a scream. You cannot take him. Please, Bittera. Not my baby.

She scrambled back on the bed, clutching Clouse so tightly he began to cry. All the propaganda flooded back. All the warnings, all the horror stories about what Americans did to German children. They were going to take him. They were going to hurt him or experiment on him or give him to an American family or kill him. She did not know what they would do, but she knew she could not let them take him.

The guards stepped forward. Dorothy said something sharp in English. They hesitated, but kept coming. Margaret screamed. A raw animal sound of terror and rage and complete desperation. Nine. Nine. Bittera. Please, not my baby. Please. Her screams brought other prisoners running. Women crowded at the door, watching in horror.

Some were crying. Some were shouting in German. The guards looked uncomfortable but determined. They reached for Klouse. Margarett fought them with all her strength, but she was weak from childbirth. Exhausted, no match for trained soldiers. They pried her fingers from the blanket. They lifted Klouse from her arms.

Klouse was crying now, a high whale of distress. Margarett was sobbing, reaching for him, trying to stand, but falling back against the pillows. My baby. Give me my baby, please. Ba, please. Dorothy was saying something. The translator was trying to speak, but Margaret could not hear anything except Klouse’s crying and the rushing sound of her own blood in her ears. The guards carried Klouse out of the room. The door closed.

His crying faded into the distance, and Margarette collapsed onto the bed, sobbing so hard she could not breathe. certain she would never see her son again. That night was the longest of Margaret’s life. She lay in the recovery room, staring at the ceiling, her arms empty, her breasts aching with milk that had nowhere to go.

She had cried until she had no tears left until her throat was raw and her head pounded. Now she just lay there hollow and broken, waiting for dawn. The other women had tried to comfort her. They brought her water, held her hand, whispered reassurances that meant nothing.

They are just following rules, one said. They will bring him back, said another. But Margaret could not believe them. Why would the enemy bring him back? Why would they show mercy after everything else was taken? She thought of Klouse alone in some American nursery, surrounded by strangers, crying for her. She thought of his tiny hands reaching for comfort that would not come.

She thought of all the ways this could end badly. The war had taught her that hope was dangerous, that trust led to betrayal, that the world was cruel and getting cruer every day. When the first light of morning crept through the window, Margaret heard footsteps in the hallway. Her heart began to pound. The door opened.

Dorothy came in and she was carrying a bundle wrapped in a white blanket. Clouse alive, crying, Margarett sat up so fast her head spun. Clouse, is that Klouse? Dorothy smiled and walked over to the bed. She placed Klouse in Margarett’s arms and he immediately stopped crying, nuzzling against her chest, seeking milk. He is hungry, the translator said.

He cried most of the night. The nurses could not comfort him. He wants his mother. Margaret stared down at her son, touching his face, his hands, counting his fingers again to make sure he was whole. He was clean. He smelled like soap and powder. His diaper was fresh. He was fed. He was fine. They had not hurt him.

They had not taken him away forever. They had just done what they said they would do, taken him to the nursery for the night, then brought him back in the morning. She began to cry again, but this time from relief so intense it hurt. Dorothy patted her shoulder awkwardly and said something in English.

The translator said, “She says you can keep him with you during the day, but at night for one more week, he should sleep in the nursery where the nurses can watch him to make sure he is healthy. After that, he can stay with you in the barracks.” Margaret nodded, unable to speak. She understood now. It was not cruelty. It was not some evil American plot. It was just medical care.

They wanted to make sure Klouse was healthy, that he was feeding properly, that he was safe. It was kindness disguised as rules. Mercy hidden behind procedures. Later that morning, after Klaus had nursed and fallen asleep, Dorothy took Margaret to see the nursery. It was in a small building next to the infirmary, painted white with cheerful yellow curtains in the windows.

Inside there were six cribs, all but one empty. Klaus’s crib had his name written on a card. Klouse Wolf Gang, October 12th, 1945. The nursery was warm and bright. There were supplies, diapers, blankets, bottles, soap, powder, everything a baby might need. On the wall was a schedule showing when each baby should be fed, changed, and checked.

It was organized and clean and safe. Margaret stood there looking at this small room where her son had spent the night and felt something crack open inside her. This was what her country could not provide. This was what Germany had lost the ability to do. Care for its most vulnerable.

American prisoners of war, even enemy babies, received better care than German civilians at home. The contrast was so stark it hurt to acknowledge. For the next week, Margaret spent her days with Klouse and her nights alone, letting the nursery staff care for him while she recovered. Each morning when they brought him back, she checked him anxiously, looking for signs of harm.

But he was always fine, always fed, clean, healthy. The nurses even seemed to enjoy caring for him, couping over his dark hair and bright eyes. Gradually, Margaret began to trust. Not completely. Trust was still too dangerous, but enough. Enough to sleep at night knowing he was safe. Enough to believe that maybe, just maybe, the Americans were not the monsters she had been taught they were.

On the eighth day, Dorothy brought Klaus to Margaret in the morning and said through the translator, “He can stay with you now, fulltime. We have prepared a space for you in the barracks with extra blankets and a small crib. You will still bring him for checkups twice a week, but he is yours to care for.

Margaret held Klouse and whispered, “Thank you, Dana. Thank you.” It was inadequate, but it was all she had. Moving back to the women’s barracks with a newborn was challenging. Klouse cried at night, waking the other women.

Some complained, but others helped, taking turns walking him when Margaret was too exhausted, singing German lullabies, sharing tips from their own children. Klouse became the barracks baby, a small piece of hope in a place that had known so little. Jimmy, the guard who had carved the rattle, often stopped by to see Klouse. He would make faces through the window, making Klouse kick and wave his arms.

Once he brought a small stuffed bear, worn and obviously old. From my nephew, the translator said, “He outgrew it. Margarette accepted it with tears in her eyes. These small kindnesses, these ordinary human moments were breaking down the walls Margaret had built around her heart. The enemy was feeding her child. The enemy was giving him toys.

The enemy was treating him like he mattered, like he was not just the son of a defeated nation, but a baby who deserved care and comfort. Late at night, nursing Klouse in the darkness while the other women slept, Margaret thought about the future. What would she tell her son when he was older? How would she explain that he was born in an enemy camp, cared for by American nurses, given toys by American guards? How would she explain that the enemy had been kinder to him than his own country could have been? The truth was complicated and painful.

Germany had destroyed itself chasing glory and ended up with ashes. America had fought a war and somehow come out stronger, more prosperous, more human. The contrast was undeniable. And Klouse, innocent Klouse, was living proof of that contrast. Margaret did not know what the future held.

Eventually, they would be repatriated to Germany, sent back to the ruins. But until then, she had this, a warm barracks, enough food, clean water, and a healthy baby. It was more than she had dared hope for. And it came from the hands of the enemy. And so that moment when Margaret screamed as the guards took Klaus away, certain she would never see him again, became the turning point in her understanding of the world. The terror she felt was real.

The propaganda she had believed was real. But what happened next changed everything. They were not taking Klouse to hurt him. They were taking him to care for him. The American nursery with its clean cribs and trained nurses was not a place of cruelty, but of mercy. The enemy had treated her child better than her own country could have.

That truth was almost unbearable to accept, but it was truth nonetheless. Years later, back in Germany, Margarett would tell Klouse the story. She would tell him about the camp in Louisiana, about Dorothy, the nurse who held her hand during labor, about Jimmy, the guard who carved him a rattle.

She would tell him that sometimes the enemy shows you more humanity than your own people, and that truth is complicated and painful and necessary. Klouse grew up understanding something that many of his generation did not. that propaganda lies, that enemies can be merciful, and that the most powerful weapon in war is not violence, but dignity.

The Americans had defeated Germany with bombs and tanks. But they had truly won by treating prisoners like human beings, by feeding children, by caring for the vulnerable. That is the story worth remembering. Not just what happened in the war, but what happened after. In the camps, in the quiet moments, in the spaces where ordinary people chose mercy over revenge.

If this story moved you, please take a moment to like this video and subscribe to our channel. These forgotten histories need to be remembered and shared. The women like Margaret, the babies like Klouse, the guards like Jimmy, and nurses like Dorothy. They all played a part in showing that even in the darkest times, humanity can prevail. Thank you for watching and we will see you in the next