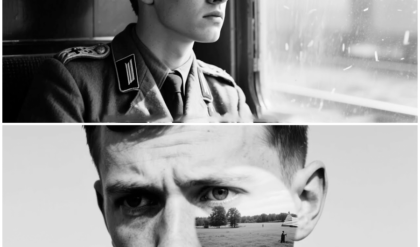

March 27th, 1945, somewhere east of the Ryan River, Hupman Erns Barkman sat in the turret of his disabled Panther tank, watching American Sherman tanks encircle his position. The right track had been blown off by an artillery shell. Black smoke poured from the engine compartment. His crew was dead or scattered. He was 24 years old, and he was certain he had hours to live.

For the past three weeks, the propaganda newspapers had been explicit. The Americans take no prisoners. Gerbal’s broadcast warned. They are gangsters, not soldiers. They will torture you. They will humiliate you. They will work you to death in their minds. Barkman had seen the leaflets dropped from Allied planes promising fair treatment under the Geneva Convention.

He did not believe them. Nobody did. These were the same people who had firebombed Dresden. The same forces that had obliterated entire German cities from the air. His hands shook as he climbed down from the turret, raising them above his head. The spring rain soaked through his black panzer uniform.

He could taste diesel, smoke, and blood in his mouth. Through the haze, American infantry approached, rifles raised. “This is it,” he thought. “This is where it ends.” He thought about his mother in Keel, about the small farm where he had grown up, about the girl he had kissed before deployment, whose letters had stopped coming 6 months ago.

He thought about the stories he had heard from Vermach soldiers returning from the Eastern Front. Stories of Soviet camps where men disappeared forever. The Americans would be the same. He knew it. Everyone knew it. The first GI reached him. A young man barely 20 years old with mud on his face and a rifle pointed at Barkman’s chest.

The German officer closed his eyes. But what happened next would change everything he thought about Americans. The American soldier did not shoot. Instead, he lowered his rifle and said something in English that Barkman could not understand. The tone was not harsh. It was almost gentle. Another soldier approached. This one with a red cross armband.

A medicit? The medic asked in broken German. Wounded? Barkman shook his head, too stunned to speak. His left arm had been grazed by shrapnel, blood seeping through his uniform, but he barely felt it. The medics saw it anyway and immediately began cleaning the wound. “Sit,” the American said, gesturing to a fallen log. “Sit down, Barkman. Saturday.” His legs felt like water.

He watched as the medic, his name tag read Kowalsski worked on his arm with careful hands. Not rough, not vengeful, just professional. The way you would treat anyone who needed help. Another American approached an officer by his bearing, though Barkman could not read the insignia.

“Lieutenant, maybe he carried a canteen.” “Water?” the officer asked, offering it. Barkman stared at the canteen. It had to be a trick. They would accuse him of trying to escape. They would beat him for taking it, but his throat was so dry and the officer was still holding it out, waiting patiently. He took the canteen with shaking hands and drank. It was just water. Clean cold water.

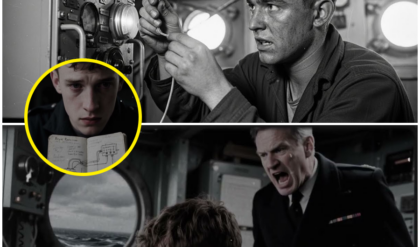

Name? The lieutenant asked, pulling out a small notebook. Barkman. Ernst Barkman. Hman. Second SS Panzer Division Doss Reich. He said it defiantly, expecting the SS designation to mean something terrible. Instead, the lieutenant just wrote it down. You are a prisoner of war now, Captain. You will be treated according to the Geneva Convention.

You understand? Barkman nodded, though he did not believe it. Not yet. They gave him a cigarette, an American cigarette, much better than the airsoft tobacco he had been smoking for months. They gave him a chocolate bar from something called a Kration. They let him sit there for 20 minutes smoking and eating chocolate while his wounds were bandaged before leading him to a collection point where other German prisoners sat under guard. None of them were being beaten. None of them were being shot. They were just sitting there waiting. Was this

loose? asked another German tanker, a young entroysier with haunted eyes. What is happening? I do not know, Barkman admitted. They are. They are treating us like soldiers. The young soldier laughed bitterly. Wait until we get to the camp. But even that first night at a temporary holding area in a bombedout factory, the Americans brought them soup. Actual hot soup. They set up latrines.

They gave them blankets. An American sergeant even returned a watch that had been confiscated after checking it was not military equipment. Barkman lay on the concrete floor that night, wrapped in a scratchy American blanket, trying to understand what was happening. None of it made sense. These were not the monsters from the propaganda films.

These were just men, tired, muddy men who happened to be on the other side. He fell asleep, confused, and for the first time in weeks, not terrified. The P camp at Fort Dicks, New Jersey, was nothing like Barkman expected. After a week in a transit camp in France, he’d been loaded onto a Liberty ship with 300 other German PS and transported across the Atlantic. He’d spent the entire voyage expecting to be thrown overboard or locked in a flooded hold.

Instead, they’d been given bunks, regular meals, and access to the deck for fresh air. When they arrived at Fort Dicks in midappril 1945, Barkman’s first thought was, “This can’t be a prison camp.” There were barracks, not cages. There was a messaul with actual tables. There was a recreation yard with a volleyball net.

There was even a small library with German books, though most were propaganda-free classics like Gerta and Schiller. You will work, the camp commandant, Colonel Morrison explained through an interpreter, 6 days a week, eight hours a day. You will be paid in camp script that can be used in the canteen. You will be treated according to international law.

Any complaints can be filed through your camp spokesman. Any abuse by guards will be investigated. Barkman looked around at the other prisoners. They were equally stunned. The work wasn’t hard labor in minds as Gerbles had promised. Instead, Barkman found himself assigned to a maintenance crew repairing trucks. Other prisoners worked in the camp kitchen or in agricultural details on nearby farms or in light manufacturing.

The hours were reasonable. The guards, while watchful, weren’t cruel. But the real surprise came 3 weeks after his arrival. On May 8th, 1,945, the war in Europe ended. Barkman heard the news in the mesh hall. Germany had surrendered unconditionally. The thousand-year Reich had lasted 12 years. He sat at a long wooden table surrounded by other panzer crewmen trying to process it.

Everything he’d fought for was gone. His unit was destroyed. His country was occupied. And here he was sitting in New Jersey eating beef stew that was better than anything he’d had in the Vermach in years. An American officer approached his table. Captain Robert Thorne from the ordinance department. He spoke decent German, learned from his grandmother, Hopeman Barkman. Ernst looked up. Wary. Yeah.

I understand you commanded Panthers on the Eastern Front. Is that correct? Yes. Where was this going? And you fought in Normandy at Morta? Yes. Barkman tensed. Were they going to investigate him for war crimes? He’d fought hard, but he’d followed the laws of war. He thought he had.

Anyway, Captain Thorne pulled up a chair. How would you like to do something useful while you’re here? That’s how Erns Barkman, former SS tank commander, found himself being driven to the Aberdine proving ground in Maryland to evaluate American tanks. The drive from Fort Dicks to Aberdine took 4 hours. Barkman sat in the back of a jeep with two MPs watching the American countryside roll past green fields, intact farms, towns that hadn’t been bombed, children playing in yards, women shopping without fear. It was almost obscene. All this life, this normaly

while Europe was a graveyard. At Aberdine, he met a team of American tank designers, engineers, and testers. They wanted German expertise. They wanted to know what the Panther did better than the Sherman, what the Tiger’s advantages were, where American tanks could improve.

“Why are you asking me?” Barkman asked Captain Thorne that first day. “The war is over.” Thorne looked at him seriously. “The war with Germany is over, but we might need to fight the Soviets someday. And your tanks were the only ones that consistently beat Soviet armor. We need to learn from that.” It was surreal. A month ago, Barkman had been trying to kill Americans.

Now they were asking his professional opinion and taking notes. They showed him the M26 Persing, America’s answer to the German heavies. It was a beautiful machine, heavier armor than the Sherman, a 90 mm gun that could penetrate anything the Germans had built, and that American reliability. “What do you think?” asked a young engineer named Miller. Barkman walked around the tank slowly. professional instincts taking over.

The armor is well sloped. Good work. The gun is excellent. Better than our Panther 75 mm. But the transmission, what about it? It’s in the front. That’s a vulnerability. Our Panthers put the transmission in the back. If you take a hit to the front, you lose mobility immediately. Miller wrote that down. What else? For three weeks, Barkman spent his days at Aberdine, testing tanks, writing reports, having technical discussions with American engineers.

They treated him like a colleague, not a prisoner. They asked his opinion and implemented some of his suggestions and design modifications. One afternoon, Barkman was in the proving ground cafeteria, which the Americans let him use, eating the same food as the engineers, when Miller sat down across from him. “Can I ask you something personal?” Miller said. Of course.

Why’d you fight for them? The Nazis. I mean, you’re clearly a smart guy. You had to know what they were doing. It was the first time an American had asked him that directly. Barkman sat down his coffee, thinking carefully. When I was 17, he said, “Germany was broken. My father couldn’t find work. We were hungry. The Nazis promised to make Germany strong again, and they did.

At first, by the time I understood what they really were, I was in uniform. And then I was fighting to keep my crew alive, not for ideology. Miller nodded slowly. My grandparents came from Bavaria in 1923. Sometimes I think that could have been me if they’d stayed. Yes, Barkman said quietly. It could have been. Another day, Captain Thorne invited Barkman to his office.

On the desk was a photograph of Thorne’s family, his wife, and two young daughters. “They’re beautiful,” Barkman said. “Thanks.” Thorne pulled out another photograph. “This was my brother, Michael. He died at Herkin Forest in November.” Barkman froze. He’d fought at Herkin. I’m I’m sorry. Yeah. Thorne looked at the photo for a long moment.

“You know what the crazy thing is? If I’d met you there, one of us would have killed the other. But here now you’re helping us build better tanks to protect the next generation of guys like Michael. I don’t understand how you can forgive. I don’t forgive the Nazis. Thorne interrupted. But you’re a soldier. Same as me. You did your job. Now we do ours, which is learning from this whole nightmare.

So maybe it doesn’t happen again. The most surreal moment came when the engineering team celebrated a successful test with a barbecue. They invited the German prisoners who’d been helping with technical consultations. About 20 men in total. American engineers and German PS stood around a grill eating hamburgers and drinking Coca-Cola, discussing tank suspensions and armor angles.

Someone brought out a baseball and gloves and tried to explain the rules to confused Germans. A radio played Glenn Miller, whose music Barkman recognized from intercepted broadcasts during the war. He stood there with a hamburger in his hand, surrounded by men he’d been trying to kill two months ago, and laughed at a joke about the Panthers tendency to catch fire. It was absurd. It was impossible. It was happening.

Barkman wrote letters home censored, but allowed telling his mother he was safe and well treated. He did not mention the tank testing that was classified, but he tried to convey that Americans were not what the propaganda had claimed. In his private diary, which he kept in shorthand German, he was more explicit.

June 3rd, 1945. Today, Miller showed me the new transmission design for the M2601. They incorporated my suggestion about the gear ratios. I cannot believe they are doing this. In the Vermacht, a private suggestion would never reach an officer. Here, if the idea is good, they use it. No wonder they won the war. June 15th, 1945.

Captain Thorne brought Schnaps to the office. Real German schnaps from before the war. We toasted to better days. He meant it. I think I did, too. July 1st, 1945. I see now that everything we were told about the Americans was a lie. They are not soft. They are not decadent. They are practical, innovative, and they value individual initiative over blind obedience.

They won because they are better at war than we were. Not despite their weakness, but because of their strengths. Gerbles lied about everything. The other German prisoners of war noticed his changed attitude. Some resented it, diehard Nazis who could not accept that their ideology had been wrong, but most were like Barkman, exhausted, disillusioned, and grateful to be alive and well treated.

One evening in the barracks, a former Tiger commander named Ralph Schneider asked him, “Do you think we were the bad guys?” Barkman looked at him for a long time. “Yes,” he finally said. “I think we were.” The American treatment of German prisoners of war was not an accident. It was policy implemented from the top. General Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied forces in Europe, had issued explicit orders.

Prisoners would be treated, according to the Geneva Convention, no exceptions. Not because the Germans had reciprocated, they often had not, but because it was the right thing to do, and because it was practical. American military doctrine recognized that well-treated prisoners provided better intelligence.

They were more willing to talk, more likely to give accurate information, and sometimes, like Barkman, they could provide valuable technical expertise. But it went deeper than practicality. It was about values. The United States had built its identity on the idea that all men were created equal, that certain rights were inalienable.

Even in war, even with enemies, those principles mattered. Soldiers who violated them face court marshal. When Private Eddie Slovic was executed for desertion, the only American soldier executed for that offense in World War II, it sent a message. We hold our own accountable. The contrast with Axis treatment of prisoners was stark.

In German camps, Soviet prisoners of war died by the millions from starvation, exposure, and outright murder. In Japanese camps, Allied prisoners were worked to death, starved, and brutally beaten. The death rate in German prisoner of war camps for American prisoners was about 1%. For Soviets, in German camps, it was nearly 60%.

Barkman learned these statistics from American newspapers in the camp library. They shocked him, even though he had served on the Eastern Front and had some idea of the brutality there. “We did not know,” he told Captain Thorne one day, reading about the liberation of concentration camps. “Some people did not,” Thorne said carefully. “But some did. It was a distinction Barkman would wrestle with for the rest of his life.

” By the summer of 1945, Barkman’s perspective had completely transformed. The Americans had done more than treat him well. They had challenged every assumption he had held about them, about the war, about his own side. In July, they showed him and other German technical consultants footage from the liberation of Bergen Bellson.

They did not make them watch, but the offer was there. Barkman watched. He felt sick for days afterward. I fought for that, he wrote in his diary. I did not know it was happening, but I fought for the regime that did it. How do I live with that? He found an answer of sorts in the work. If he could help the Americans build better equipment, maybe he could contribute something positive.

Maybe he could be useful instead of just a war criminal who had gotten lucky. His technical reports were meticulous. He evaluated the M26 Persing against the Panther point by point. Armor advantage persing gun advantage persing mobility roughly equal reliability massive advantage persing crew comfort advantage persing the M26 is in every measurable way superior to the Panther Alfurung G.

He concluded its only disadvantage was arriving too late to affect the war’s outcome. Had these tanks been available in Normandy the campaign would have ended months earlier. It was not easy to write that. It was his professional assessment. His expertise turned against his own side. But it was also the truth. And maybe the truth was all he had left to contribute.

Barkman was one of approximately 430,000 German prisoners of war held in the United States during and after World War II. The survival rate was over 99%. They worked, but under regulated conditions. They were paid poorly, but paid. They were housed adequately. They received medical care.

Many German prisoners of war worked on American farms where labor was scarce due to the war. Some formed friendships with farming families. A few even returned after the war to settle permanently in America. Repatriation began in 1946 and continued through 1948. Some Germans did not want to go back. Their homes were in Soviet occupied zones or destroyed or they had simply grown fond of America, but most returned to help rebuild.

Barkman was repatriated in January 1947, nearly 2 years after his capture. By then, he had spent 18 months as a technical consultant for the United States Army Ordinance Department. His final report was classified until 1973. Erns Barkman returned to a Germany he barely recognized. The country was divided, occupied, and devastated. His hometown of Keel was rubble.

His mother had survived, living with relatives, but his father had died in an air raid in 1944. He had no job, no prospects, and a past he could not escape former SS, even if he had been just a tank commander. But he had one asset, his technical expertise and a letter of recommendation from Captain Robert Thorne.

In 1948, Barkman was hired by Majurus Deuts, a German truck and vehicle manufacturer trying to rebuild. His experience with American automotive engineering learned at Aberdine was valuable. He helped them retool their factories, incorporate new techniques, and modernize their designs. He never designed weapons again.

He could not. The moral weight was too heavy. In 1951, he married Anna Hoffman, a war widow he had met at church. They had three children. He told them about the war honestly when they were old enough to understand. He did not hide his service. He did not glorify it either.

I fought for an evil regime, he told his oldest son in 1967 when the boy was 16 and asking questions. I did not realize how evil until it was too late. The Americans taught me that fighting well does not make you right. And they taught me that even enemies deserve dignity. He maintained correspondence with Robert Thorne until Thorne’s death in 1982. They never met again in person.

Barkman could not afford the trip, and Thorne never made it to Germany, but they wrote letters every Christmas. Thorne’s daughters visited Germany in 1975, and Barkman showed them around, including the rebuilt Cologne Cathedral. Your father saved my life, he told them, not just physically, spiritually.

He showed me there was a way forward after everything. The American treatment of German prisoners of war was part of a larger strategy that extended far beyond the war. When Secretary of State George Marshall announced the European recovery program, the Marshall Plan in 1947, it represented a radical approach to defeated enemies.

Instead of punishing Germany into oblivion, as the Allies had done after World War I, America invested billions in rebuilding, West Germany became a prosperous democracy and a crucial Cold War ally. The contrast with Soviet occupied East Germany was stark. Many Germans who had been prisoners of war in America became advocates for democracy and close United States German relations. They had seen American society firsthand.

They understood that democracy was not weakness, it was strength. Barkman was one of thousands of former German soldiers who became part of the Bundesphere, West Germany’s new military. Formed in 1955, his American training and contacts were valuable. He served as a technical adviser on armored vehicle procurement, helping evaluate whether West Germany should buy American, British, or domestic tanks.

He recommended American designs. In 1985, for the 40th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, a German television station interviewed Barkman about his experiences. He was 64 years old, silver-haired, speaking carefully about his past. “What did the Americans teach you?” the interviewer asked. Barkman thought for a long moment.

“They taught me that how you treat your enemies defines who you are more than how you treat your friends. They could have beaten us, starved us, humiliated us. They had every right. We had started the war. We had committed atrocities. But they chose to treat us as human beings who had made terrible mistakes. Do you think you deserve that treatment? No. But I am grateful for it.

And I have tried to spend my life earning it retroactively. He died in 1999, age 78. At his funeral, his family displayed two photographs on his coffin. one of his Panther crew from 1944 young men who had mostly died in the war and one of the American engineering team at Aberdine in 1945 smiling around a tank in his will he left a letter to be published postumously the final paragraph read I expected Americans to behave like Nazis when they did not when they treated me with dignity and humanity I had not earned it broke

something in me the propaganda the hatred the certainty they broke it by being better than we were not just at war, but at peace, at being human. I spent 50 years trying to understand that lesson. And I am not sure I ever fully did. But I know this. The world would be better if everyone asked, “What would the Americans at Aberdine have done?” That is the standard.

That is what decency looks like. Ernst Barkman’s story is not unique. Thousands of German, Italian, and Japanese prisoners of war experienced similar transformations in American custody. They expected brutality and found humanity. They expected revenge and found respect. This was not weakness. It was strategic genius wrapped in moral principle.

By treating prisoners well, America accomplished several things simultaneously. First, they gained intelligence and expertise like Barkman’s technical knowledge. Second, they demonstrated that democratic values were not just propaganda. They were real, even in war. Third, they planted seeds for the post-war peace. When those prisoners of war returned home, they became ambassadors for American values.

They had seen that democracy was not decadence, that freedom was not chaos, that treating people well was not naive. It was powerful. The contrast with the Soviet approach was instructive. German prisoners of war in Soviet camps were brutalized, starved, and worked to death. Those who survived returned home bitter and traumatized.

In West Germany, former prisoners from America advocated for partnership with the United States. In East Germany, former Soviet prisoners were silent, broken. This had strategic consequences. West Germany became America’s staunchest European ally. The Wiff, the economic miracle, was built partly by men who had seen American prosperity and wanted to replicate it.

The bundes was trained in American doctrine by officers who respected and understood United States methods. But the lesson goes deeper than strategy. It is about what war does to us and what it does not have to do. War brings out the worst in humanity. Violence, hatred, dehumanization, but it also reveals who we are at our core.

The Americans at Fort Dicks and Aberdine proving ground could have taken revenge. Nobody would have blamed them. Instead, they chose to see the humanity in their enemies. That choice rippled forward through decades. It shaped the post-war world. It helped transform enemies into allies and bitter hatred into productive partnership.

Today, when America faces conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, the question persists, how do we treat defeated enemies? How do we handle prisoners? What values do we uphold even when it is difficult? Barkman’s story suggests an answer. When we treat people with dignity, even our enemies, we do not just win wars. We win the peace that follows.

We demonstrate that our values are not conditional. That freedom and human rights matter even in the hardest circumstances. This does not mean being naive. It does not mean ignoring war crimes or pretending atrocities did not happen. It means holding ourselves to a higher standard because that standard is what makes us who we are.

The Americans who treated German prisoners of war well were not saints. They were soldiers doing their jobs, following orders based on values they believed in. But those values mattered. They changed lives. They changed history. In our current moment, with conflicts ongoing and new threats emerging, these stories remind us why American principles matter, not just as ideals, but as practical tools for building a better world.

When we treat enemies as irredeemable monsters, we perpetuate cycles of violence. When we see them as human beings who made terrible choices, who can learn, change, and contribute, we create possibilities for transformation. That is what happened at Aberdine Proving Ground in 1945. A German tank commander expected punishment.

He received an education and democracy delivered through small acts of kindness and respect. He never forgot it. Neither should we. Erns Barkman climbed down from his disabled panther on March 27th, 1945. Certain he would die. He was wrong. Instead of death, he found humanity. Instead of revenge, he found respect.

Instead of an ending, he found a new beginning. The Americans who captured him did not just follow the Geneva Convention. They embodied the principles their country was founded on. They showed him that democracy was not weakness, that freedom was not decadence, and that treating enemies well was not naive. It was the most powerful weapon in their arsenal.

This was not just American military doctrine. This was American character. Helpman Ernst Barkman expected a prison camp. The Americans gave him a tank and asked him to test it. In doing so, they did not just learn how to build better weapons. They taught a former enemy what it meant to be free. He never forgot.

Do you have a family story about prisoner of war treatment during World War II from either side? Did your grandfather serve at a prisoner camp or was he a prisoner himself? Share your stories in the comments. These personal histories matter. Next week, the Japanese pilot who attacked Pearl Harbor and lived next door to the sailor who survived it. Subscribe so you do not miss