Virginia, August 1943. The ship groaned against the Norfick dock as dawn broke over American soil. Inside the hold, German prisoners stood shoulderto-shoulder, breathing the last air of captivity at sea. They had been told what awaited them. Starvation, torture, camps worse than anything the Reich had designed.

Through propaganda films and whispered warnings, they knew Americans were savages who took no mercy on the defeated. What they saw in their first 24 hours on American soil shattered that certainty more completely than any bomb. The shock began the moment they stepped onto the dock. August 4th, 1943, 6:00 in the morning, Norfick, Virginia. Corporal Klaus Miller climbed the metal stairs from the ship’s hold, his legs unsteady after 14 days at sea.

Salt air hit his face, thick and warm. Beside him, hundreds of German prisoners shuffled up behind, blinking in sudden daylight, preparing themselves for what came next. They had spent the voyage bracing for the moment when American savagery would reveal itself.

The gang plank descended with a groan of metal on metal. Clouds stepped onto American soil. The dock stretched wide, wooden planks weathered gray by ocean spray. An American MP stood at the bottom, rifle slung over his shoulder, and Klouse waited for the shout, for the blow, for the beginning of horrors the propaganda had promised. The MP yawned.

He checked his wristwatch like a man bored with routine. Another MP nearby cracked a jokelouse could not understand, and both guards laughed. No one hit anyone. The air itself felt wrong. Klouse breathed deep, tasting something he had not encountered in months. Freshness, the smell of growing things.

Beyond the dock, Virginia stretched green and whole, trees thick with summer leaves, buildings standing undamaged against a blue sky. Friedrich Han stood frozen beside him, staring at the shoreline like a man seeing a ghost. “Look,” Friedrich whispered in German. The buildings, they are not bombed. Klouse looked. Every structure stood complete. Windows reflected morning sun.

Warehouses lined the port, their roofs intact, their walls unscratched by war. Ships moved in the harbor with casual efficiency. Cranes lifted cargo. Workers called to each other across the docks. It was a port in wartime. Yet, it looked like a port at peace. In Germany, the cities were burning. here. Nothing burned at all. The MPs gestured them toward a processing area.

The prisoners moved in formation. Years of military discipline keeping them orderly even in defeat. Klouse expected interrogation, perhaps torture disguised as questioning. Instead, they were given forms. An American clerk with wire- rimmed glasses sat at a folding table, checking names against a manifest. He looked bored. He looked like he would rather be having coffee.

“Name?” the clerk asked in accented German. “Miller.” Klaus Miller. The clerk made a mark. Next. That was it. No threats, no violence, just bureaucracy. They were photographed, fingerprinted, given prisoner numbers. Klouse became 3152847. The American photographer, a corporal with red hair and freckles, positioned each man in front of a white sheet and snapped photos with mechanical efficiency. “Hold still,” he said. “Don’t smile.

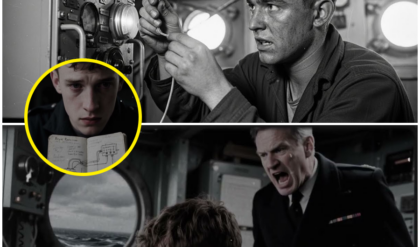

” As if any of them would smile. But his tone was not cruel. It was merely professional, like a man doing a job he had done a thousand times. Then came the trains. Klouse stared at them and felt something fundamental shift in his understanding of the world. These were not cattle cars. These were not the box cars that had carried them across Europe. Packed 50 men deep with no seats and one bucket in the corner.

These were passenger cars, Pullman cars with windows and cushioned seats and overhead racks for luggage they did not have. Inside, an MP said not unkindly. Long ride ahead. Klaus climbed aboard. The interior was clean, worn, but clean. The seats had fabric covering, blue and slightly faded. The windows opened. Fresh air moved through the car, carrying the scent of American summer.

Clouse sat down and felt the cushion give beneath him. Beside him, Otto Verer touched the armrest with the tentative care of a man handling something fragile. This is a passenger train. Otto whispered, “They are putting us on a passenger train.” Friedrich, sitting across the aisle, ran his hand along the window frame.

In Germany, I rode to the front in a box car. 50 men, 3 days, no seats. We took turns leaning against the walls to sleep. The train lurched and began to move. Through the windows, Virginia passed by in a stream of green. Fields rolled past, unplowed by tank treads. Farmhouses stood whole. Barns held their roofs. Cows grazed in pastures like the world was not at war.

Children played in a yard, and one looked up to wave at the passing train. an American child waving at German prisoners. Klouse waved back before he could stop himself. The cognitive dissonance was crushing. Every piece of evidence before his eyes contradicted everything he had been taught.

America was supposed to be weak, starving, barely holding itself together. Instead, he was riding through a landscape of abundance so complete it seemed obscene. Where were the ration lines? Where were the ruined buildings? Where was the suffering that propaganda had promised would greet them? The train rolled through the morning and into afternoon. The guards walked the aisles, checking on prisoners, making sure no one attempted anything foolish.

But their vigilance was casual. One guard stopped beside Klaus’s seat and offered cigarettes around. American cigarettes. Klouse took one, his hands shaking slightly, and the guard lit it for him with a Zippo that clicked open with practiced ease. “Smoke them if you got them,” the guard said in English. Klouse did not understand the words, but he understood the gesture.

He drew smoke into his lungs and tasted tobacco that was not airzat, not mixed with sawdust or dried leaves. Real tobacco, American tobacco. The guard moved on and Klouse sat there smoking, watching America pass outside his window, feeling certainty crumble with every mile. By noon, the heat increased.

The American South in August was an oven, but the windows stayed open and the breeze helped. Klouse dozed, woke, dozed again. Sometime in the afternoon, the train stopped at a small town for water. The prisoners were allowed to step onto the platform to stretch their legs to breathe air that was not thick with the smell of too many men in too small a space. A woman appeared, American, middle-aged.

She carried a basket covered with a checkered cloth. She approached the nearest guard, spoke to him briefly, then began handing out sandwiches to the prisoners. Klouse took one, staring at it like an artifact from another world. White bread, ham, cheese, lettuce. An American woman was giving food to German prisoners of war. “Eat,” she said in German.

The word heavily accented, but unmistakable. “You must be hungry.” Klouse bit into the sandwich. The bread was soft. The ham was real. The cheese tasted of something other than deprivation. He chewed slowly, and around him, other prisoners did the same. All of them silent. All of them trying to process what was happening.

Otto stood beside him, eating his sandwich with tears running down his face. Not from sadness, from the sheer incomprehensibility of kindness from an enemy. The train whistle blew. They reorted. The journey continued through the window. Klouse watched America unspool in an endless reel of normaly. Gas stations with cars waiting for fuel.

Grocery stores with people walking out carrying bags full of food. Churches with white steeples pointing toward a sky that held no bombers. Every mile was evidence against the Reich’s narrative. Every scene contradicted the propaganda that had sustained him through 2 years of war.

Friedrich leaned across the aisle. Do you remember the films they showed us in training? Klouse remembered. Films of Americans torturing prisoners. Films of cities and chaos. Films designed to make surrender seem worse than death. I remember. They lied, Friedrich said quietly. About everything. They lied about everything. Klaus did not answer.

He was too busy watching a group of American children playing baseball in a field beside the tracks. Their laughter audible even over the train’s rattle. In Germany, children hid in bunkers. Here they played games. Evening approached.

The train had been moving for hours through Virginia, through the Carolas, deeper into the American South. Heat pressed against the windows, even as the sun began its descent. Klaus’s uniform stuck to his back with sweat. Beside him, Otto fanned himself with his cap. Friedrich had fallen asleep, his head against the window, exhausted by the strangeness of everything. The train began to slow.

Through the window, Klouse saw buildings appear. Wooden structures freshly built stretching across cleared land. Guard towers punctuated the perimeter. Barbed wire caught the late afternoon light. A sign at the entrance read Camp Hearn in white letters against dark wood. The train hissed to a stop.

The MP at the front of the car stood and announced something in English. Klouse caught only one word, home. They filed off the train onto a gravel platform. The Texas heat was different from desert heat, Klaus realized. Thicker, humid. It wrapped around him like a blanket he could not shed.

Before him stretched the compound, and despite the wire in the towers, something about it looked wrong for a prison camp. Too organized to new American soldiers waited to receive them. But again, their demeanor puzzled Klouse. No shouting, no rifles pointed. One sergeant actually helped an older prisoner down from the train car, catching his elbow when he stumbled. The gesture was so automatic, so devoid of malice that Klouse stopped walking just to stare at it.

Processing began immediately. They were led into a wooden building that served as administration. More forms, more photographs. A medical officer examined each man. Klouse was directed to remove his shirt. The American doctor, a captain with gray threading through his brown hair, pressed a stethoscope against Klaus’s chest, checked his eyes, his throat, his ears.

He discovered the poorly healed shrapnel wound on Klaus’s shoulder, and frowned. “This should have had stitches,” he said in careful German. “You’ll have a bad scar.” He cleaned the wound with alcohol that stung, applied fresh bandages with practiced gentleness, and made a note on a chart. Klouse stood there shirtless in an enemy medical facility, receiving better care than he had gotten from his own field medics.

The doctor handed him a slip of paper. Report to the infirmary tomorrow. We’ll check the healing. Klouse took the paper. He did not understand. This man was treating him like a patient, not a prisoner. Outside, twilight was falling. The prisoners were divided into groups and led toward the barracks.

Klouse walked with Otto and Friedrich, following an American corporal whose rifle remained slung over his shoulder, unthreatening. They passed what looked like a kitchen building, and through the open door came smells that made Klaus’s stomach clench with sudden, desperate hunger. Meat cooking, bread baking, real food. The barracks loomed ahead. Long, low buildings with screened windows and wooden steps leading to doors that stood open. The corporal gestured them inside.

“Find a bunk,” he said in broken German. “Dinner in 1 hour.” Klouse stepped into the barracks and stopped. The other prisoners behind him stopped too, creating a bottleneck at the door. The barracks was clean, newly built. It smelled of fresh pine and disinfectant. And down each side in two neat rows stood beds, metal-framed beds with mattresses, with sheets with pillows. Otto made a sound that was half laugh, half sobb. Beds, he whispered.

They have given us beds. Klaus walked to the nearest unoccupied bunk and sat on it. The mattress compressed beneath him, and the springs creaked softly. He ran his hand over the sheet. It was thin, institutional, but it was clean. A folded blanket sat at the foot of the bed. A pillow rested at the head, slightly lumpy, but real.

He lay back, staring at the ceiling, and felt springs supporting his body instead of dirt or metal floor. Friedrich claimed the bunk above Klouse. He climbed up and lay there in silence for a long moment before saying, “I spent 6 months sleeping on the ground. Before that, train floors. Before that, a tent in rain.

I have not slept in a bed since I left Munich. Around them, other prisoners were doing the same thing, sitting on beds, touching sheets. Some lay down immediately. Others stood staring as if afraid the beds would disappear if they looked away. One older man, a sergeant named Hans, who rarely spoke, sat on his bunk and wept quietly, his face in his hands. The hour passed too quickly. A whistle blew.

The corporal appeared at the door. Dinner time. Follow me. They walked to the mess hall in a loose formation. The building was larger than Klouse expected with long tables and benches and windows that led in the last of the evening light. American soldiers sat at some tables eating and talking.

The prisoners were directed to their own section, but not separated by walls or guards. Just space, just custom. The serving line began at one end of the hall. Klouse took a metal tray from a stack, picked up utensils, and shuffled forward. Behind a counter, American cooks in white aprons ladled food onto trays.

Real cooks, not prisoners, not forced labor. American soldiers serving German prisoners dinner. The first cook dropped a piece of fried chicken onto Klaus’s tray. The second added mashed potatoes with a pool of brown gravy in the center. The third spooned green beans beside the potatoes. The fourth placed two slices of white bread with pats of butter on the tray’s edge.

At the end of the line, pictures of milk sat on a table, cold and sweating in the heat. Klouse carried his tray to a table and sat. He stared at the food. Otto sat beside him, staring at his own tray. Friedrich sat across from them, and he made no move to eat either. All three of them looked at the fried chicken, the mashed potatoes, the butter, the milk, and could not begin.

This is not real, Otto finally said. It is real, Friedrich replied. Which means everything else was a lie. Klaus picked up his fork. He cut into the chicken. Steam rose from the meat. He took a bite, chewed slowly, tasted fat and salt and seasoning, and understood that he was eating better food as a prisoner of war than he had eaten as a soldier in the Vermacht.

Better food than his family was eating in Stoodgart. better food possibly than he had ever eaten in his life. Around him, hundreds of German prisoners came to the same realization. The mess hall filled with the sounds of eating, but it was quiet eating, stunned eating. Some men ate mechanically, faces blank with shock.

Others ate slowly, savoring each bite like it might be the last. A few could not eat at all, overwhelmed by the cognitive dissonance of abundance in captivity. Hans, the older sergeant, sat with his hands folded, staring at his full tray. He had not touched his food. A younger prisoner beside him asked if he was ill. Hans shook his head.

I am thinking, he said quietly, about my daughter. She is 11. In our last letter, she wrote that they had soup for dinner. Just soup, potato peels, and water. and I am here in an enemy camp looking at fried chicken. The guilt was crushing, but the hunger was real. Eventually, Hans picked up his fork and ate.

After dinner, they were shown the facilities. The latrines were clean with running water and actual toilets. The showers had hot water. Hot water. Klouse stood under a shower head that evening, feeling water hotter than he had experienced in 2 years run over his skin, washing away sweat and fear and the grime of travel, and he could not stop shaking.

By 9:00, the compound settled into evening routine. Prisoners returned to barracks. Some played cards, others wrote letters home, though they would be weeks in transit. A few ventured to the canteen where they discovered they had been issued 80 cents in script, enough to buy cigarettes or chocolate or soap. August became September. The heat did not break.

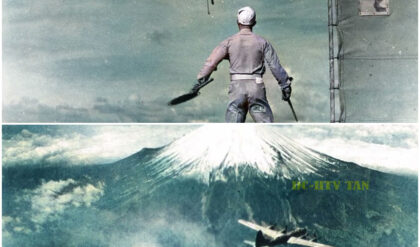

Texas heat, Klouse learned, was different from desert heat. It pressed down with humidity, made the air thick enough to taste. The prisoners adapted. Some worked in the camp’s maintenance crews. Others volunteered for the work details that left the compound each morning in trucks that rumbled down farm roads to fields that stretched beyond sight.

The war had taken America’s young men overseas. Fields across the South needed hands. The War Department, following Geneva Convention protocols, offered prisoner labor to farmers at $1.50 per day. The prisoner received 80 cents in canteen script. The arrangement satisfied everyone except some locals who called the camps the Fritz Ritz and wrote angry letters about prisoners eating steaks while Americans rationed butter.

Klouse volunteered for fieldwork, anything to get out of the compound to feel the sun on his back doing something other than waiting. The truck carried them 20 m to a cotton farm where the owner, a weathered man named Curtis Whitfield, stood waiting with his hat pulled low against the morning glare. “Curtis studied the prisoners with eyes that had seen too many droughts to be surprised by anything.” “You boys ever picked cotton?” he asked.

“No one had.” Curtis showed them how. The motion of pulling the bowls without crushing them. The way to work a row without trampling the plants. The cotton came away and white tufts that filled the sacks they dragged behind them. The work was hard. The sun climbed and the heat increased and Klaus’s back began to ache.

But there was a rhythm to it, a simplicity that was almost peaceful after years of war. At noon, Curtis’s wife brought lunch. She arrived in a pickup truck, the bed loaded with thermoses and baskets. Klouse expected to eat separately from the Americans under guard. Instead, Curtis waved them all over to the shade of a live oak that grew beside the field. “Come on,” he said. “Food’s getting cold.

” They sat together, Germans and Americans, prisoners and guards. Curtis’s wife served sandwiches wrapped in wax paper thick with ham and cheese and lettuce. There were pickles, potato chips, and lemonade, cold and tart, and so good. Klouse drank three glasses.

Curtis’s wife refilled his glass each time without comment, without judgment, like it was the most natural thing in the world to give lemonade to German prisoners of war. “You boys speak English?” Curtis asked, biting into his sandwich. “Some?” Klaus said. His English was broken, learned from a textbook in school. “Where are you from?” “Stoodgart.” Curtis nodded like this meant something to him, though Klaus doubted he knew where Stoodgart was. They ate in silence for a moment.

Then Curtis said, “My son’s over there in France fighting your countrymen, I reckon.” Klaus did not know what to say to that. “I am sorry,” he tried. “Not your fault. Wars war. Politicians stardom. Young men die in them. Been that way since Cain and Abel.” Curtis finished his sandwich and stood, brushing crumbs from his shirt. “Back to work, boys. Cotton won’t pick itself.

” That evening, returning to camp, Klaus sat in the truck bed, watching Texas pass by, fields and farmhouses and endless sky. The guard riding with them, a corporal from Ohio named Miller, offered cigarettes around. Klouse took one. They smoked in silence, the wind pulling the smoke away in streams. “Not so bad, is it?” Miller said.

Klouse did not answer right away. He was thinking about the lemonade, about Curtis’s wife serving food without fear, without hatred, about Curtis himself, whose son was fighting Germans in France, sharing lunch with German prisoners in Texas. The contradictions were too large to fit in his mind at once.

“No,” Klouse finally said, not so bad. By October, the routine had established itself. wake at dawn, breakfast in the messaul, work details for those who volunteered. Klouse worked Curtis’s farm twice a week. Other days he helped with construction projects at the camp, building new barracks for the prisoners still arriving by train.

The work was paid, the food was plentiful, and in the evenings there were classes. The camp offered education, correspondence courses from nearby universities, math, English, agriculture, stenography. Some saw it as American propaganda. Others saw it as opportunity. Friedrich Han enrolled in every class he could. Before the war, he had been studying philosophy at university. That life seemed impossible now from another world.

But here in a P camp in Texas, he could study again. The classes were taught by American instructors, some military, some civilian. They did not preach. They did not force ideology. They taught mathematics and language and agricultural techniques and the subtext was clear without being spoken. There is another way to live.

There is another way to think. Otto Verer took English classes. His instructor was a retired school teacher from Houston named Mrs. Campbell who rode out to the camp twice a week in her Chevrolet. She was 60 years old and treated the German prisoners like her own students, correcting their pronunciation with patience, praising their progress with genuine warmth.

Otto could not reconcile this woman with the propaganda images of Americans as violent barbarians. Mrs. Campbell brought books. She brought magazines. She brought newspapers that showed the war from the American perspective. And though some prisoners refused to read them, Otto did. He read about battles he had fought in, described from the other side.

He read about American production numbers, the factories turning out tanks and planes and ships faster than Germany could destroy them. He read about a country that was not starving, not weak, not on the verge of collapse. One evening in November, Mrs. Campbell stayed after class. She spoke to Otto in English slowly to help him understand. You’re a bright young man, she said.

What will you do after the war? Otto had not thought that far ahead. The war was not over. Germany was still fighting. I will go home, he said to Munich, to my family. And then he did not know the future was fog. You could come back here, Mrs. Campbell said after. America needs bakers, carpenters, farmers, men willing to work, men who want to build instead of destroy. The idea was absurd. He was a prisoner, an enemy soldier.

But Mrs. Campbell spoke like it was possible, like the war would end and borders would open and life would continue in ways he could not yet imagine. That night, Otto lay in his bunk and thought about Mrs. Campbell’s words. He thought about Curtis Whitfield and his wife with her lemonade. He thought about the guards who played cards with prisoners, who shared cigarettes, who treated them not as monsters, but as men. He thought about the food and the classes and the strange, disorienting abundance of America. The propaganda had

prepared him for cruelty. It had not prepared him for kindness. December brought cooler weather. Not cold, not by German standards, but enough that jackets felt good in the mornings. The camp decorated for Christmas. Some prisoners found it offensive. This mixing of German soldiers and American holiday cheer.

Others found it necessary. Home was a year away, maybe more. The war continued. Letters from Germany took months to arrive. When they arrived at all, Christmas in a P camp in Texas was not what any of them had imagined, but it was better than spending it in a foxhole in North Africa. The camp chaplain, Captain Robert Hayes, organized a service. He was Catholic, but he welcomed everyone.

The chapel was one of the wooden buildings, simple and unadorned. Klouse attended because he had nothing else to do. He sat in a pew and listened to Captain Hayes speak about peace, about hope, about the possibility of redemption even in the middle of war. After the service, Captain Hayes approached him.

Merry Christmas, son, he said. Klouse nodded. Thank you. You have family back home in Stogart. My mother, my sister. I’ll pray for them, Captain Hayes said. and he meant it. Klouse could see it in his eyes. An American chaplain praying for a German soldier’s family. The world had become very strange. That afternoon, Curtis Whitfield arrived at the camp with a truck full of gifts.

He had organized it with other farmers in the area, a collection of blankets, socks, cigarettes, and candy. The guards allowed him to distribute them to the prisoners who had worked his farm. Klouse received a wool blanket and a pack of cigarettes. Curtis shook his hand. “Merry Christmas,” Curtis said. “War can’t stop that.

” Klouse held the blanket after Curtis left, feeling the weight of it in his hands. A farmer whose son was fighting Germans in Europe had just given him a Christmas present. Klouse sat on his bunk and tried to make sense of it. Otto sat across from him, unwrapping a bar of chocolate Curtis had included in his package. “None of this makes sense,” Otto said quietly.

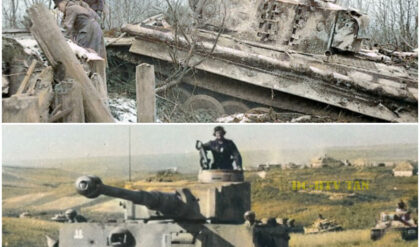

No, Klaus agreed. But it was happening anyway. January 1944 arrived. The war entered its fifth year. In Germany, cities were burning under Allied bombing. In the Pacific, Americans were island hopping toward Japan. In Texas, German prisoners of war picked cotton and attended classes and ate food they could hardly believe was real.

The cognitive dissonance was crushing for some. Several prisoners, diehard Nazis who refused to accept the evidence before their eyes, formed secret groups within the camps. They enforced loyalty. They punished those who seemed too friendly with Americans.

At Camp Hearn, a prisoner named Hugo Krauss made the mistake of learning English too well. He worked as an interpreter for the American guards. He reported clandestine activity. He openly criticized the Third Reich. On December 21st, 1943, seven men beat him with pipes and boards studded with nails. They cracked his skull. They broke both arms.

Hugo Krauss died 6 days later, and no one in his barracks came to his aid because fear still had teeth. The murder shocked the camp. American authorities investigated, separated suspected Nazis from the general population. But for Klouse and Otto and Friedrich, the lesson was clear. Even here, even in this strange paradise of abundance, the war was not over.

The ideology had not died. There were men who would kill to preserve it. Yet the work continued. The friendships continued. Curtis Whitfield still brought lemonade. Mrs. Campbell still taught English. The food kept coming, three meals a day, more than they needed. And slowly, meal by meal, class by class, the certainty that had brought them across the ocean continued to crack.

By spring of 1944, Klaus had worked Curtis’s farm for 8 months. He knew the rhythms of Texas seasons now, the way cotton grew, the careful timing of planting and harvest. Curtis trusted him to work unsupervised, to handle equipment, to make decisions about which fields needed attention. One afternoon, Curtis said, “You ever think about staying?” Klouse looked up from the row he was working.

“Staying? After the war? You could get a visa. Plenty of farms need workers. Pays good for men who know what they’re doing.” The idea hung in the hot afternoon air. Stay in America. Stay in Texas. Leave Germany behind. Leave the ruins. Leave the ash.

Build a life here where the sky was wide and the food was plentiful and people treated you like a human being. instead of a number. I do not know, Klouse said. Think about it, Curtis said, and he walked away, leaving Klouse standing in the cotton field with dirt under his fingernails and possibility weighing heavy in his chest. May 1945, the war in Europe ended. Hitler was dead. Germany had surrendered unconditionally.

The news reached Camp Hearn over radios, through newspapers, in letters from the International Red Cross. The prisoners gathered in the compound, listening to reports of devastation, of cities reduced to rubble, of millions dead. This was victory for the allies. For the prisoners, it was the confirmation of defeat.

Klouse sat on his bunk and read a letter from his mother that had taken 4 months to arrive. She was alive. His sister was alive. Their house was gone, destroyed in a bombing raid. They were living with relatives on a farm outside Stoutgart. Food was scarce. Work was scarce. The future was uncertain. She asked if he was well, if he was safe, if he knew when he would come home. He was safe. He was wellfed.

He was living in a barracks with a roof and walls while his family lived in the ruins of Germany. The guilt was enormous. The war was over, but the prisoners stayed. President Truman decided America still needed the labor. The factories were converting from war production to peaceime goods. Farms still needed hands.

So, the prisoners remained working, waiting. Some grew angry, others accepted it. Klouse found himself in the strange position of wanting to go home and wanting to stay. Both desires pulling at him with equal force. By summer, the camp began emptying. Repatriation started slowly. Ships crossed the Atlantic, carrying prisoners back to a Germany that no longer existed.

Not in the form they remembered. Klouse was scheduled to leave in August 1946, 3 years since he had arrived on American soil. His last day of work, Curtis drove him to the farm one final time. They worked the fields together in silence, the familiar rhythm of cotton picking filling the hours. At lunch, Curtis’s wife made fried chicken, the same meal Klaus had eaten on his first day in Texas.

They sat under the live oak eating without speaking much. Because there was too much to say and no good way to say it. You ever change your mind? Curtis said finally about staying. You write me. I’ll help with the paperwork. Klouse nodded. He did not trust himself to speak. That evening, Curtis drove him back to camp. At the gate, he stopped the truck and extended his hand. Klaus took it. They shook.

A farmer and a prisoner. Two men who should have been enemies who had somehow become something else. You’re a good man, Klouse, Curtis said. Don’t matter where you were born. You’re a good man. Klouse climbed out of the truck. Curtis drove away, dust rising behind his tires. Klouse stood at the gate watching until the truck disappeared.

And then he walked into the compound for the last time, carrying the weight of three years in America that had taught him everything his country had tried to hide. The ship that carried Klaus back to Germany was crowded and gray, nothing like the Pullman cars and cushioned seats of his arrival. They sailed in September 1946, and the Atlantic crossing took two weeks of cold and discomfort.

When they docked at Bremer Haven, Klaus stepped onto German soil and found ruins. The port was a skeleton. The city beyond was worse. Rubble stretched in every direction. People moved through the streets like ghosts, thin and holloweyed, dressed in whatever they could find. He made his way to Stoodgart by train, sitting in a box car with a hundred other returnees.

All of them silent. All of them trying to reconcile the Germany they remembered with this wasteland of broken stone and shattered lives. Stoodgart was unrecognizable. The landmarks he had grown up with were gone. The house he had been raised in was a crater.

He found his mother and sister in a single room of a farmhouse 15 km outside the city. And they held each other and cried. That night his mother made soup from potatoes and carrots. It was thin, barely flavored, nothing like the meals in Texas. But it was home. Klouse ate slowly, tasting the difference, understanding for the first time the full measure of what America had shown him. What was it like? His sister asked.

In America, in the camps? Claus set down his spoon. How could he explain? How could he describe abundance to people who were starving? How could he tell them about Curtis Whitfield and his lemonade? About Mrs. Campbell and her English classes? About guards who played cards with prisoners? about a country that fed its enemies better than Germany fed its citizens.

“It was not what we were told,” he said finally. “None of it was what we were told.” In the years that followed, Klouse rebuilt his life in Germany. He worked construction, married, raised children, but he never forgot Texas. He never forgot the cotton fields in the wide sky, and the farmer who had treated him like a man instead of a monster.

In 1953, he applied for immigration. In 1955, he received his visa. He brought his family to America, to Texas, to a state that had once imprisoned him and now welcomed him as a citizen. He was not alone. Thousands of German prisoners returned after the war. They had been captured expecting cruelty and found kindness.

They had been prepared for starvation and discovered abundance. The treatment they received in American P camps did more to defeat Nazi ideology than any propaganda could have because it is easy to hate an enemy when you are told they are monsters. It is much harder to hate them when they give you lemonade. Otto Verer became an American citizen in 1958. He opened a bakery in Houston.

Friedrich Han finished his philosophy degree at the University of Texas and taught for 30 years. Curtis Whitfield’s son came home from France in 1945, alive and whole. Curtis continued farming until he died in 1972, and at his funeral, Clouse stood beside the grave, and wept for a man who had shown him what forgiveness looked like. The camps are gone now.

The wooden barracks were torn down, sold for scrap, repurposed. Only monuments remain. small markers in Texas fields noting that here once prisoners of war learned that their enemies were human too. Historians studying the period note that the American P program was one of the most successful re-education efforts in history.

Not because of what was taught, but because of how prisoners were treated. They came expecting hell and found something stranger. They found people who, despite the war, despite the ideology, despite everything, chose to be decent. Years later, interviewed by historians, Otto Verer said, “We were trained to believe Americans were weak, decadent, barely human.

Then they gave us beds and fed us stake and treated us with respect we did not deserve. That broke Nazism in our hearts more effectively than any bomb ever could.” Klaus Mueller, speaking to students in 1980, put it differently. “On my first day in America, I expected to be shot. Instead, I was given a pillow. Everything I had been told was a lie, and understanding that took the rest of my life. The sun still rises over Texas.

The fields still grow cotton. The sky remains as wide as it ever was. And somewhere in the archives, in letters and diaries and fading photographs, the story remains of men who crossed an ocean expecting death and found instead a second chance at life. That was their first day in America. The rest took decades.