May 9th 1,941 1,235 hours North Atlantic 300 m south of Iceland. Oblitant Fritz Julius Limp clung to wreckage in water so cold it felt like knives cutting through his skin. Around him what remained of U 110’s crew struggled in the swells. 32 men from a compliment of 47, the rest still entombed in the submarine sinking beneath them.

The North Atlantic stretched out black, endless, utterly indifferent to whether they lived or died. For 18 months, Limp had commanded U 110. 12 Allied merchant ships sent to the bottom. 68,000 tons of steel and cargo turned to artificial reefs. He’d stalked convoys from the western approaches all the way to Gibraltar, striking under cover of darkness, vanishing before the escorts could mount a counterattack.

The propaganda had a name for it, dluclely site, the happy time. Uboats ranged almost unchecked across the Atlantic, throttling Britain’s maritime lifeline, dispatching Allied sailors to frigid graves with mechanical efficiency. Now limp floated in his own oil slick, hypothermia creeping through his limbs, watching HMS Bulldog circle the debris field like a predator sizing up wounded prey.

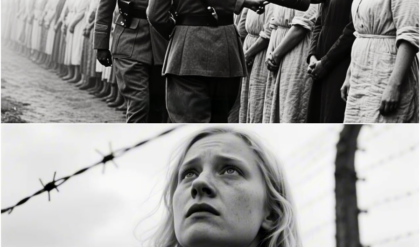

The destroyer’s depth charges had forced U 1110 to the surface, crippled, helpless, finished. Limp had screamed the order to abandon ship before Bulldog’s guns could tear them apart. Now his men drifted in the spreading oil, waiting for British machine guns to complete what the depth charges had begun.

The propaganda had been explicit on this point. The British Royal Navy showed no mercy to yubot crews. They would strafe survivors in the water. Payback for all those merchant sailors who drowned when torpedoes struck without warning in the middle of the night. Capture meant torture. It meant execution. Better a quick death by drowning than whatever the British had planned.

Limp watched Bulldog close the distance. Her main guns trained on the Germans bobbing in the swells. This was it. The accounting. Heed sunk British ships, killed British sailors. Now the bill had come due. He closed his eyes, prayed it would be quick. A voice rang out across the water in German. Grab the lines.

We’re pulling you aboard. Limp’s eyes snapped open. British sailors were hurling rope ladders over Bulldog side. Life rings splashed into the water. No guns firing. No one taking aim. They were rescuing them. He stared, unable to process what he was seeing. His radio operator, Klaus Wild, 19 years old and terrified, grabbed a life ring and got hauled up the destroyer’s hull.

Then his engineer, then his torpedo man. British hands dragging German sailors from the sea, wrapping them in blankets, shephering them to shelter below decks. Still shaking with cold and confusion, Limp grabbed a rope himself. British sailors who should have been shooting him instead pulled him upward. He collapsed onto Bulldog’s deck, shivering so violently he could barely see straight.

His mind refusing to reconcile propaganda about British savagery with the reality of Royal Navy sailors, stripping off his soaked clothing and bundling him in drywool blankets. A British petty officer crouched beside him, speaking careful, practiced German. You’re safe now. Well get you warm. Medical officer will check you over shortly.

through chattering teeth. Limp managed. Why? Why not just shoot us? The petty officer looked genuinely puzzled. Because you’re in the water, mate. That’s when the fighting stops. The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign of the war, had been raging since the conflict’s first day in September 1939 when U30 torpedoed the passenger liner SS Athenia.

By spring 1941, the German hubot were winning decisively. Operating in coordinated groups called Wolfpacks, they developed tactics that devastated Allied convoys. Surface at night when radar couldn’t detect them. Attack multiple targets simultaneously. Dive before escorts could respond. Reload. Repeat. The mathematics were brutal.

Yubot sank merchantmen faster than Britain could replace them. Churchill would later write, “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the Yuboat peril. I was even more anxious about this battle than I had been about the glorious airfight called the Battle of Britain.

” German submarine crews called it good luck zite, the happy time. They hunted Allied shipping with near impunity, returned to French bases as heroes, received medals and promotions. Yubot commanders became celebrities in the Reich. Propaganda films portrayed them as modern knights, clean warriors fighting honorable submarine warfare against the British Empire’s merchant navy.

The reality was considerably darker. Yubot attacks were typically executed at night against unarmed merchantmen. Torpedoes struck without warning. Ships went down in minutes. Merchant sailors had perhaps seconds to abandon ship before frigid Atlantic water swallowed them. Many drowned outright. Others succumbed to hypothermia in lifeboats.

Some were simply never found. The British knew exactly what the Ubot were doing. Through ultra intelligence, they were reading decoded German communications, tracking attacks in near real time, counting losses. Merchant sailors understood the risks every time they cast off. Convoy escorts knew they were protecting vulnerable ships against enemies who struck from darkness and disappeared before retaliation was possible.

This context, years of merchant sailors dying in freezing water, thousands of tons of supplies lost, Britain’s very survival threatened by submarine blockade made what happened next extraordinary. By May 1941, British anti-ubmarine warfare had evolved from desperate reaction to systematic hunting. New technologies were shifting the balance.

Improved sonar tracked submerged submarines more accurately. Centimentric radar detected surfaced submarines even at night. Highfrequency direction finding triangulated yubot radio transmissions. Depth charges with improved fusing detonated at precise depths. More importantly, escort groups had developed tactics specifically designed to kill hubot.

Convoy escorts no longer simply defended merchantmen. They hunted submarines aggressively, pursuing sonar contacts until the submarines were forced to surface or were destroyed. The hunters were becoming the hunted. U10 had departed Laurant on March 15th 1,941 under Oberite Limp’s command. The mission patrol northwest of Capefinair.

Intercept Gibraltarbound convoys. Sink as much tonnage as possible. Standard Wolfpack operations for two months. U 110 operated successfully. Five confirmed kills, no damage. Limp’s reports to BDU Yubot command were optimistic. British anti-ubmarine measures remained ineffective. Convoys were poorly defended.

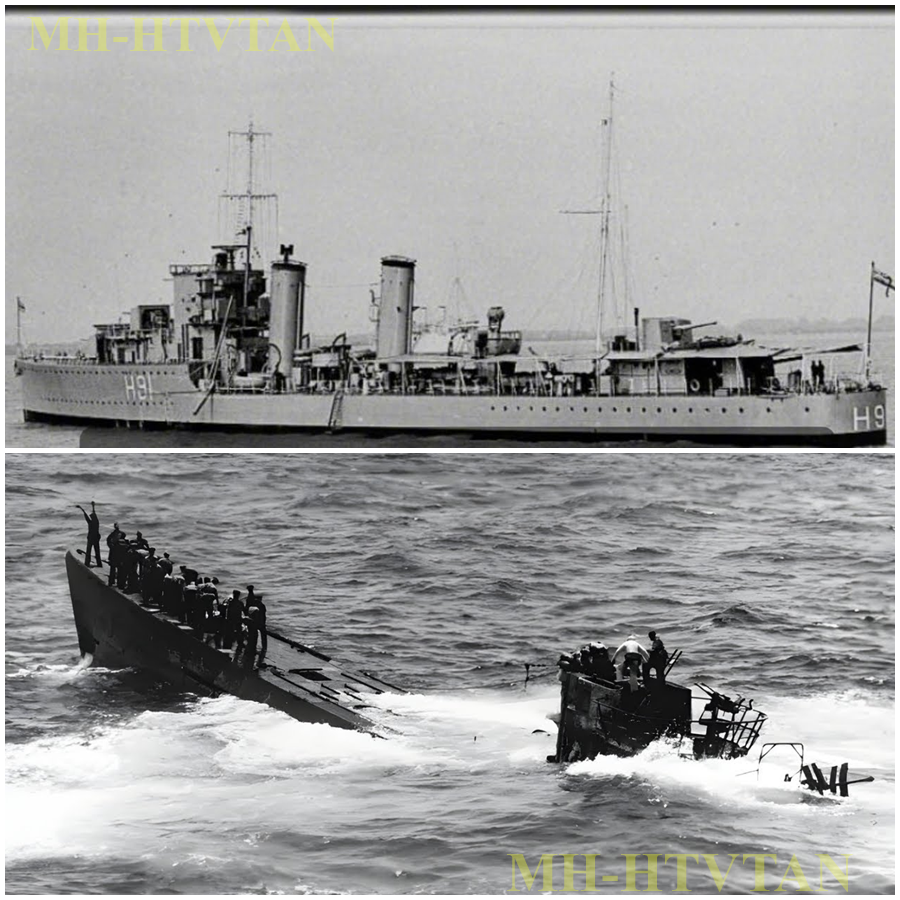

Escorts were cautious. Depth charge attacks were inaccurate. [Music] On May 9th, U 110 detected convoy OB 318. Approximately 40 merchantmen with weak escort, a target-rich environment, limp positioned for attack, fired torpedoes at two ships from periscope depth, and prepared to dive and evade. Instead, HMS Orretia and HMS Broadway detected U 110’s periscope wake, established sonar contact, and executed an immediate depth charge attack.

The charges detonated close enough to rupture U 110’s pressure hull, knock out electrical systems, jam the dive planes, and fill compartments with chlorine gas from shattered battery cells. Limp had no choice. Surface or die trapped underwater. He ordered an emergency blow. Compressed air forced water from the ballast tanks.

The submarine rose uncontrollably toward daylight. U 1110 broke the surface at 1,230 hours, listing badly, unable to dive, dead in the water. HMS Bulldog closed immediately. Guns trained, preparing to either finish the crippled submarine or accept its surrender. What happened next violated every assumption German submarine crews held about British behavior through his binoculars.

Bulldog’s captain, Commander Joe Baker Creswell, observed U 110’s hatches, opening, crew emerging, hands raised. The submarine was clearly finished. Engines dead, taking on water, no longer a threat. Standing orders were explicit. Destroy all enemy vessels. Take prisoners only when strategically valuable.

Baker Creswell made his decision in seconds. The Yubot was modern, possibly containing intelligence materials. Capturing it intact could provide immense intelligence value. Code books, ciphers, perhaps even an enigma machine. But first, he needed to secure the crew before they could properly scuttle the boat.

He gave orders that contradicted everything German propaganda had predicted. Cease fire. Prepare to take prisoners. Bulldog closed to 200 m. British sailors threw ropes and life rings. German sailors expecting bullets hesitated before grabbing the lines. Some were too injured or hypothermic to climb. British sailors went down rope ladders into the same freezing water where their enemies were drowning and physically hauled Germans aboard.

Radioman Klaus Wild, 19 years old, and terrified, grabbed a rope, and was pulled up Bulldog’s side by sailors who’d lost friends to yubot attacks. They stripped his soaked clothing, wrapped him in blankets, led him below decks where steam heating could prevent hypothermia. I kept waiting for them to beat us.

Wild recalled in a 1985 interview. We’d sunk their ships, killed their sailors. I’d been told the British were savages who tortured prisoners. Instead, they gave us hot tea and dry clothes. A British sailor couldn’t have been older than me. Offered me a cigarette and said, “Rough day, eh?” as though we were colleagues who’d had a workplace accident rather than enemies who’d been trying to kill each other minutes before.

The rescue took 20 minutes. 32 Germans pulled from the water. 15 had died in the submarine or drowned before reaching safety. The survivors sat on Bulldog’s deck, shivering, wrapped in Royal Navy blankets, drinking tea from chipped enamel mugs, unable to process the disconnect between propaganda and reality.

While his crew recovered, Baker Creswell made another calculation. U 110 was still floating, badly damaged but not yet sunk. If a boarding party could reach her before she went down, intelligence materials might be recovered. He selected eight volunteers, sailors who understood the risks. U 110 could sink at any moment. She could explode if scuttling charges were set with delayed fuses.

Chlorine gas from damaged batteries could kill anyone who entered. This was extremely dangerous work with uncertain rewards. The boarding party took a motor wher across, climbed onto U 110’s slippery deck, forced open the hatches, and descended into the dying submarine. What they found changed the war. In the radio room, code books documenting current naval cipher settings.

In the captain’s cabin, sailing orders, grid charts, operational instructions. In the radio operator’s station, a three rotor enigma machine, still functional, ready to be recovered. The boarding party worked frantically, passing materials to the wher, code books, charts, mechanical parts, anything that might have intelligence value.

The submarine was settling deeper, water rising through lower compartments, the whole structure groaning from structural damage. After 30 minutes, with water reaching the control room deck plates, the boarding party evacuated with everything they could carry. 15 minutes later, U 110 slipped beneath the waves, taking her remaining secrets to the ocean floor.

Baker Creswell immediately imposed absolute secrecy. The captured Germans were isolated, forbidden from communicating with each other or other prisoners. They were told repeatedly that U 110 had sunk with all hands, that no capture had occurred, that their survival must never be disclosed to other Germans.

The intelligence materials were rushed to Bletchley Park, where crypton analysts used them to break current German naval Enigma settings. For months afterward, British intelligence could read Yubot communications in near real time, a decisive advantage that would help turn the Battle of the Atlantic. The Germans never knew.

BUU recorded U 110 as lost with all hands. No investigation occurred. No security procedures changed. The Enigma compromise remained secret until after the war. The 32 survivors from U 110 were transported to Britain, processed as prisoners of war, and sent to camps under strict security protocols. Their treatment followed standard British procedures.

adequate food, weatherproof housing, medical care, work assignments within Geneva Convention guidelines. Nothing exceptional. Just the systematic decency Britain extended to all captured enemies for submarine crews who’d been told the British would torture them. The normaly was profoundly disorienting. I spent 3 years in a camp in Lanasher.

Plaus Wild later wrote, “We worked on farms, received regular meals, had access to medical care. Guards were professional firm but not cruel. We could write letters home under censorship. We had religious services. It was imprisonment, yes, but imprisonment that followed rules. No torture, no starvation, no executions.

Everything we’d been told about British brutality was propaganda. The psychological impact was significant. These men had participated in warfare that killed tens of thousands of merchant sailors. They’d sunk unarmed ships without warning. They’d left survivors in freezing water without assistance.

Now they were receiving systematic care from the nation they’d tried to starve into surrender. The contradiction forced a reconsideration of everything German propaganda claimed about British character. If the British weren’t barbaric toward captured enemies, if they followed civilized standards, even when dealing with yubot crews, then perhaps other propaganda claims were equally false.

What the Germans didn’t understand was that British behavior followed traditions older than any ideology. Maritime customs dating back centuries governed conduct even during war. The Royal Navy had been shaped by 300 years of experience that taught fundamental lessons. Sailors respect other sailors regardless of nationality.

Enemies in combat become shipwrecked mariners once in the water. The sea itself is deadly enough without adding human cruelty. Professional naval forces maintain standards that separate them from pirates and murderers. These weren’t sentimental feelings. They were professional ethics embedded in naval culture.

You fought hard, but you fought honorably. You tried to kill enemies afloat, but you rescued them if they ended up in the water. That’s what professional navies did. Anything less was barbarism. Commander Baker Creswell articulated this philosophy in his official report. The enemy submarine was engaged and forced to surface.

Upon observing the crew abandoning ship, the decision was made to recover survivors per standard maritime law. 32 prisoners were taken aboard, treated per king’s regulations, and transferred for processing. Intelligence materials were recovered from the submarine before sinking. No moral grandstanding, no claims of mercy or compassion, just a matter-of-fact description of following standard procedures.

That casualness, treating the rescue of enemies as routine rather than exceptional, was profoundly British. The rescue of U 110’s crew wasn’t an isolated incident. Throughout the Battle of the Atlantic, British warships repeatedly rescued German submarine crews despite enormous risks. The mathematics made these rescues dangerous.

Surfacing to rescue survivors meant stopping, becoming a stationary target for other Yubot still operating nearby. Other submarines might interpret rescue operations as an opportunity for attack. Spending time recovering German sailors meant neglecting convoy protection. Every minute spent on rescue increased risk to British ships and crews.

Yet the rescues continued. Royal Navy destroyers, corvettes, and frigots pulled German sailors from the water as routine practice. Not because regulations required it, but because maritime tradition demanded it. The statistics documented systematic behavior from 1,939 to 1,945. Over 525 German submarines were sunk by British action.

Approximately 28,000 German submariners served during the war. British ships made over 4,200 rescue attempts despite tactical risk. Around 5,000 German sailors were rescued by British forces. There were 340 documented deaths of Germans in British captivity, fewer than 50 primarily from wounds sustained before capture. The survival rate for rescued Germans exceeded 98%.

These weren’t propaganda numbers. They were documented facts showing that British forces rescued German sailors routinely, treated them properly, and returned most of them home alive after the war. The contrast with German treatment of Allied survivors was absolute. German yubot generally didn’t rescue merchant sailors they torpedoed.

Standing orders prohibited taking survivors aboard except for senior officers who might provide intelligence. Allied sailors who survived torpedo attacks typically drowned in lifeboats or died of exposure. The few who reached land often did so without German assistance. Just 18 days after U 110’s capture, the same waters witnessed another dramatic rescue operation.

On May 27th, 1,941, the battleship Bismar Pride of thes Marine was sunk after 3 days of pursuit. She went down with over 2,000 crew aboard. Only 114 survived, pulled from freezing water by HMS Dorsucher and HMS Maui. The circumstances made rescue extremely risky. A yubot had been reported in the area. Bismar’s survivors were scattered across miles of ocean.

Every minute spent recovering Germans increased exposure to submarine attack. The tactical recommendation was clear. Leave them and withdraw to safety. Admiral Tovi gave different orders. Recover as many as possible. The destroyers spent over an hour pulling Germans from the water. men who’d just been shooting at British ships who’d sunk HMS Hood with massive loss of life, who represented everything Britain was fighting against.

British sailors hauled them aboard anyway, gave them blankets and medical care, treated them like shipwrecked mariners rather than hated enemies. One Bismar survivor, Bruno Rzona, recalled, “A British sailor pulled me aboard Dorsucher. I was convinced they’d throw me back or shoot me. Instead, he wrapped me in a blanket, gave me hot tea, and said, “You’re safe now.

No hatred, no revenge, just professional naval rescue.” That moment taught me more about British character than any propaganda could destroy. The pattern held across both incidents. Combat was fierce and professional, but once enemies ended up in the water, they were treated as mariners in distress. The British fought to kill.

then rescued those they’d tried to kill. That dichotomy absolute during combat, merciful afterward, was something German naval propaganda had never prepared crews to expect. Captivity in British P camps created ideological shifts among submarine crews who compared their treatment with Nazi claims about British brutality.

The process was gradual. Initial shock at not being tortured gave way to acceptance that the British followed rules even with hated enemies. This opened questions about other propaganda claims. If the British weren’t barbaric toward captured Yubot crews, the very crews who’d been strangling Britain’s lifeline, then perhaps everything else was lies, too.

Klaus Wild described his evolution. In the camp, I had time to think. We’d sunk merchant ships, sent sailors to drown in freezing water. The British had every reason to hate us. Instead, they treated us correctly. Not kindly. Exactly. But fairly guards that were professional, food was adequate, medical care was provided.

I began questioning everything I’d believed. If Nazi propaganda about British cruelty was false, what about the racial theories, the claims about Jewish conspiracy? The entire ideology I’d fought for. This transformation wasn’t universal, but it was significant. Submarine crews had been elite forces, carefully selected, highly trained. ideologically committed.

Breaking their faith in Nazi ideology required overwhelming evidence. British treatment of captured submariners provided that evidence. When German yubot veterans were repatriated after the war, many carried memories that would shape postwar German naval culture and attitudes toward Britain. They’d expected death and received rescue.

They’d anticipated torture and experienced correct treatment. The disconnect between propaganda and reality had been so profound, it rebuilt their understanding of what civilized naval warfare actually meant. The Battle of the Atlantic continued until May 1945, the longest campaign of the war, claiming more lives than any other naval theater. The British won barely.

By 1943, improved technology, better tactics, ultra intelligence, and overwhelming numbers of escort vessels had turned the battle decisively against Hubot. The happy time ended. German submarines began dying faster than they could be replaced. The Wolfpacks were hunted to extinction. But throughout the campaign, even at the darkest moments when Britain faced potential starvation, Royal Navy ships continued rescuing German submarine crews when possible.

The tradition held. Professional standards were maintained. Enemies in the water became mariners in distress. Always had been, always would be. North Atlantic, May 2003. Memorial service aboard HMS Bulldog. A different ship, but carrying the name. Veterans gathered. British sailors who’d served on convoy escorts.

German submariners who’d survived the battle. Old men now in their 80s, but still carrying memories of that frozen ocean where enemies became mariners became prisoners. And eventually something approaching friends. Klouse Wild stood at the rail looking at gray waters where he’d nearly died 62 years earlier. British sailors had pulled him from that water when letting him drown would have been easier, safer, and more justified.

That rescue had saved his life and rebuilt his understanding of what civilized behavior meant. A British veteran, a former crew member from the original HMS Bulldog, stood beside him. They’d met decades earlier at a reunion, discovered their shared history, and maintained correspondence ever since. “Still cold, isn’t it?” the British veteran said quietly. Wild nodded.

Always cold. But I remember British hands pulling me out. Remember the tea afterward. Remember thinking everything I’d been told was lies. You lot fought hard, the British veteran replied. Made life hell for the merchant convoys. Lot of good men died because of you. I know. I’m sorry. Not your fault.

You were following orders. Same as us. We were just doing our jobs. You tried to sink merchants. We tried to sink you. When you ended up in the water, different rules applied. Maritime law older than any war. They stood in silence, watching waves that looked exactly as they had in 1941. Cold, gray, endless, indifferent to human conflicts.

The British had pulled them from the sea. That simple act repeated thousands of times across six years of warfare had proven stronger than any propaganda more lasting than any ideology. It remained decades later the story that mattered that even in total war some standards held that enemies in the water became mariners in distress.

That civilization meant maintaining humanity even when it would have been easier, safer, and more justified to simply let them drown. The Royal Navy had fought hard, but it had also rescued those it fought against. That combination absolute in combat, merciful in victory was the tradition that defined professional naval service. The Germans had learned it the hard way.

Pulled from freezing water by hands that should have let them die but didn’t. And they’d carried that lesson home where it helped build a new Germany that understood what civilization actually meant.