November 23rd, 1944. Herkin Forest, Germany. An American combat medic stares into a foxhole and finds a German woman giving birth right now under artillery fire. He has 90 seconds to make a choice. A choice that will echo through three generations. This is the story of how enemies became family. How one moment of compassion created 11 lives.

How grace, even in war, ripples forward forever. The contraction tears through Rosa Becker’s body, and she screams, a sound swallowed by the howl of an incoming shell. The explosion punches frozen dirt into her face. She is crouched in a foxhole, not hers. It belonged to soldiers who fled or died. Her water broke 20 minutes ago.

It is mixing with the mud and blood coating the bottom. She is going to die here. She knows this. The baby is coming and she is going to die and no one will ever know they existed. Then a face appears above the foxhole rim. American green helmet, red cross armband, eyes wide with shock.

Corporal James Hayes of the 28th Infantry Division stares down at the pregnant German woman. and his medic training 16 weeks of treating bullet wounds and shrapnel tears has not prepared him for this. For a split second he could leave, should leave. His unit is 300 yards west, probably wondering where their medic went. Instead, he slides into the foxhole.

Rose’s hands fly up defensively. The words that come out are German, panicked, incomprehensible to Hayes, but he recognizes the universal language of terror and pain. Another contraction hits and her back arches. Hayes sees the blood on her torn dress, the impossible swell of her belly.

“Oh god! Oh god! She is having a baby right now. Here, ma’am,” he says, hands raised, medic sliding off his shoulder. Ma’am, I am I am going to help you. She does not understand English. She understands only that the enemy has found her. She is too weak to run, too far along to hide what is happening. 3 months ago, I believed Americans were monsters.

The poster showed them with apes faces, destroying our villages, attacking our women. Her husband is dead. A vermocked officer delivered that news 6 days ago with all the warmth of a weather report. She has nothing. No one. But this American is pulling things from his bag. Bandages. A canteen. His hands are shaking.

Another shell lands closer. The foxhole walls shutter. Frozen crumbles onto them both. Hayes does not run. He is cutting away the fabric of her dress with medical shears, exposing her belly. And Rosa realizes with crystalline clarity that this is actually happening. An American soldier is about to deliver her baby in a foxhole under artillery fire.

While two armies try to kill each other, two people are about to create life. 8 days earlier, Rosa had been alone in the farmhouse cellar near the Belgian border. The battle of Herkin Forest, which would last longer than Stalenrad, had turned these woods into a meat grinder. The front line moved back and forth like a violent tide.

Some days she would hear German being shouted in the trees. Other days English. She had tried to evacuate east when the Americans first arrived in October. Walked 12 miles in one day. Her pregnant belly making each step agony. Then the roads clogged with refugees moving in both directions. Nobody knew where safety existed anymore.

She turned back, rationed her mother’s preserves, melted snow for water, felt the baby kick, and wondered if her child would be born into a world at war, or if the world would end before then. The poster said Americans would show no mercy to German civilians, that they took pleasure in our suffering. I had no choice but to believe or to hope they were lies.

On November 14th, a Vermached officer brought news of Gunter’s death at the Sief Freed line. That night, she made a decision. She would wait for the baby. If the Americans came, she would beg for mercy, hope they had it to give. Eight days later, her water broke while gathering snow. The first contraction dropped her to her knees.

She stumbled toward the treeine. Some animal instinct demanding cover, darkness, safety. She found this foxhole and crawled inside as artillery erupted across the forest. Contractions came every 8 minutes. Then six. Then four. She screamed, but no one heard. The artillery was louder. Then an American face above the foxhole.

Then a choice that would echo across 60 years. James Hayes had been a combat medic for 6 months. He had treated sucking chest wounds in farmhouses, held pressure on femoral bleeds while men scream for their mothers, watched boys younger than him die because he could not work fast enough. But obstetrics never.

Yet here he was trying to remember anything, anything about delivering a baby. Support the head. Do not pull. Let the baby come naturally. Cut the cord. Wait. Do I have anything sterile? Okay, he said mostly to himself. Okay, ma’am. You are you are doing great. She did not understand the words, but she heard the tone. Steady, calm, lying. Another contraction.

Rosa screamed and Hayes saw the crown of the baby’s head. Dark hair slick with fluid and blood. Oh Jesus, it is actually happening. The baby is coming right now. He positioned himself, hands shaking. An artillery shell exploded close enough that the blast wave punched his chest. Dirt rained down.

Rosa convulsed with pain. And Hayes pressed one hand against her knee, a gesture of support, of presence of, “I am here. I will not leave.” And with his other hand, he reached to support the emerging head. “That is it,” he said. “That is it. You are doing it.” Rosa heard the gentleness in his voice. It made no sense. Americans were supposed to be brutal.

Shoot civilians on sight. Take pleasure in German suffering. This man’s hands were steady. Careful. His face. She could see it now. In the dim light was terrified. Yes, but not cruel. Not hateful. Why? The baby’s head emerged fully. Hayes’s hands cradled it, and he felt the tiny weight of a new human being in his palms.

Something ancient and overwhelming surged through him. life. Despite everything, the bombs, the bullets, the bodies he had zipped into bags this morning, life was happening right here, right now. One more push, he said, making a pushing gesture with his free hand. Come on, just one more. Rosa understood.

Not the words, but the meaning. She bore down every muscle engaged in this final brutal effort, and the baby slipped free into Hayes’s waiting hands. For one terrible second, nothing. The baby did not cry, did not move. Hayes stared at the tiny purple gray body, and panic clawed at his throat. “No. No, please. Not after all this.

” He cleared the baby’s mouth with his finger, rubbed the baby’s chest back, trying to stimulate. “Breathe. Please breathe.” Then a cough, a gasp, and the most beautiful sound James Hayes had ever heard. A baby crying, strong, angry, alive. He laughed. Actually laughed, looked up at Rosa and saw tears streaming down her face. And he carefully, so carefully, placed the baby on her chest.

“It is a girl,” he said, though she could not understand. “A girl? She is perfect. Rose’s hands trembled as they touched her daughter. She had been preparing to die, had accepted it, and now she was holding life, warm and real, and screaming. The baby quieted against her skin, and Rosa looked up at Hayes with an expression he would never forget.

Not gratitude, not yet. Something deeper, recognition, maybe. an acknowledgement that the universe had just rearranged itself in ways neither of them understood. Hayes pulled gauze from his medic bag. I need to he gestured at the umbilical cord. Cut. Tie. She nodded. Understood enough. He tied the cord in two places with sterile suture thread, then used his medical shears to cut between the ties.

The baby was officially separate now, her own person. Born in a foxhole, delivered by the enemy. While the forest tried to kill them all, Hayes wrapped the baby in the cleanest bandages he had, then pulled out his canteen. “Water,” he said, offering it to Rosa. “Drink.” She took it with shaking hands. “Drink.

” The water was cold and tasted faintly metallic, and it was the best thing she had ever consumed. “Thank you,” she whispered in German. “Dank,” Hayes recognized the word, nodded. “You are welcome.” They sat there for 90 minutes, not because they wanted to, because the artillery had not stopped. Shells were landing in a methodical, murderous pattern.

Stepping out of that foxhole meant dying. So, Hayes stayed, monitored Rosa’s bleeding, which was heavy but not catastrophic, made sure the baby was warm, waited. Rosa watched him, studied his face. He was young, maybe 22. Dark hair, cropped short, a scar on his left hand, wedding ring. He has a wife somewhere, someone waiting for him.

The propaganda said, “Americans were soulless.” But this man’s eyes kept darting between her and the baby with an expression that was not duty or obligation. It was wonder. He looked at her daughter the way her husband had looked at ultrasound photos with awe at the impossible fact of new life. name?” Hayes asked, gesturing at the baby.

“Was Ist name?” Rosa thought. She had not chosen a name yet, had not wanted to tempt fate. But now, here in this moment that should not exist, a name arrived fully formed. “And she said, “Grace” Hayes smiled. “Anja, that is beautiful.” He repeated it, the pronunciation a little off, but close enough. And Rosa realized that this American soldier would be part of Anga’s story forever.

Her daughter’s first breath had been witnessed by James Hayes. Her first moments protected by enemy hands. The shelling finally slowed. Hayes peered over the foxhole rim, scanning the treeine. We need to move, he said, gesturing toward his own lines. Aid station, doctor, you need help. Rosa understood, nodded.

Hayes climbed out first, then reached down for the baby. Rosa hesitated just for a second, then handed Anja up, watched as Hayes cradled her daughter against his chest, one armed while extending his other hand to help Rosa climb out. She was weak, blood soaked, could barely stand. Hayes steadied her and together, American medic, German mother, newborn baby.

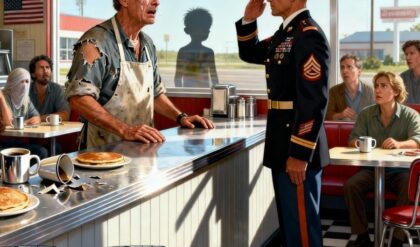

They walked out of the foxhole and into history. The American aid station was organized chaos. Wounded soldiers everywhere. medics working on three men simultaneously, a surgeon operating on a table made from barn doors. The smell of blood and disinfectant and fear. Hayes walked in carrying a baby supporting a German civilian and every head turned.

“Sir,” Hayes called to the surgeon. “I have got a woman who just gave birth. She needs attention.” Captain Morrison, exhausted, blood spattered, looked at Hayes like he had spoken Sanskrit. “You have got a what?” German civilian gave birth in a foxhole 90 minutes ago. She is bleeding, needs fluids, needs examination.

Morrison processed this with visible effort. Hayes, we have got 17 Americans waiting for surgery. I know, sir, but she will die without help. For a long moment, Morrison just stared. Then get her to the back tent. I will send someone when I can. It took 4 hours. Four hours during which Rosa sat on a cot holding Ana watching American soldiers watch her.

Some with curiosity, some with hostility, some with the blank exhaustion of men who had seen too much to care about. One more complication. Hayes stayed nearby, checked on her every 20 minutes, brought her food, canned beans, crackers, chocolate from a Kration, brought her a blanket when she started shivering. A corporal approached, short, aggressive, angry about something that needed a target.

Why are we wasting supplies on a crout? Hayes stepped between them. She is a civilian. She is German. Her husband probably killed Billy. Her husband’s dead and she just gave birth in a foxhole while shells were landing. Back off, Miller. Miller did. Not happily, but he did. Rosa watched this exchange and felt something shift inside her.

Hayes, this medic who had delivered her daughter, was defending her to his own people, putting himself between her and hostility. Why? That question circled in her mind as nurses eventually examined her and declared her stable as the baby nursed for the first time. As night fell and the aid station quieted, Hayes appeared one last time before his shift ended, squatted beside her cot.

“You okay?” she nodded. Ja. Okay. Tomorrow we will get you to a civilian camp. There is one near Aken. Safer there. Thank you, she said in careful English. You save us. Hayes shook his head. You did the hard part. He looked at Anja, sleeping against Rosa’s chest. She is tough like her mom. Rosa felt tears building. Fought them. Lost.

I think you are dead. American find me. I think dead. Hayes’s expression crumpled with understanding. No, he said quietly. No, we are not. He stopped, struggled for words. I am sorry you were afraid. She looked at him. Really looked at the exhaustion in his face, the blood on his uniform. Some of it anas, most of it not.

The wedding ring he kept unconsciously turning on his finger. He was just a man, not a monster, not a liberator, just a frightened, decent man trying to survive a war he probably did not fully understand either. “Your wife?” Rosa asked, pointing at the ring. “Sarah,” Hayes said, and his whole face softened.

“Back in Wisconsin, waiting for me.” “She is lucky,” Hayes smiled. “I am lucky,” then hesitating. “What is the baby’s full name?” “Just Anja,” Rosa thought. She had not considered a middle name. But looking at this man, this American who had given her daughter life, she knew. Anja Jameson, she said, for James, for you. Hayes’s eyes widened. You do not have to. I want you.

Give her life. She carries your name. He was silent for a long moment. Then he nodded, unable to speak. And Rosa saw his eyes glisten with tears he did not let fall. Rosa was moved to a civilian displacement camp near Aken. Tents mostly, hundreds of German refugees waiting for the war to end. But Hayes visited every week when his unit rotated back for rest.

Brought supplies, baby clothes scred from somewhere, formula, diapers made from cutup sheets, brought candy for the other children, brought his smile, which mattered more than any of it. On his third visit, Rosa asked him, “Why do you come? You have duty other places.” Hayes considered the question, “Because I was there when she was born. That means something.

I cannot just walk away. But I am enemy. You’re a mother. That is not enemy territory.” Rosa laughed. Actually laughed. She had not done that in months. You are strange American. Yeah. Hayes agreed. I get that a lot. December 10th, 1944. Hayes’s last visit came just before his unit moved east toward the Rine. I do not know when I will be back, he said.

Maybe not until after the war ends. Rosa nodded. She had expected this. You keep safe for Sarah. And you keep safe, for Anna. He looked at the baby, now 2 weeks old, alert and healthy. She is going to grow up strong. I can tell because she was born in war. because she had you fighting for her.

Hayes pulled something from his pocket. A piece of paper with an address. When the war is over, if you need anything, write me. Wisconsin, my parents address. They will forward it wherever I am. Rosa took the paper with trembling hands. I will write. I promise. Hayes stood to leave. Then paused. Rosa, what you said about thinking Americans would hurt you? The propaganda you believed? J.

We were told things too about Germans, about what you would do to prisoners, about how cruel you would be. He met her eyes. I guess we were both lied to. She nodded slowly. Yeah, both lied to. Maybe that is the lesson that the enemy is just people, scared people trying to survive. Maybe, Rosa said.

Or maybe the lesson is some people choose good even in war. Hayes smiled. Yeah, that is better. He left. Rosa watched him walk away and part of her wanted to call him back to say something more meaningful, something that captured what this impossible friendship meant. But the words did not exist, not in German or English. So she just held Ana and whispered, “Remember him when you are old enough to understand.

I will tell you about the American who gave you life.” They wrote for 60 years. Not frequently. Sometimes years would pass between letters, but consistently Christmas cards with photos, birth announcements, updates on life’s milestones. Rosa returned to the farmhouse after the war. found it damaged but standing, rebuilt, remarried eventually a kind man, a teacher who loved Ana as his own, had two more children, lived a quiet life.

But she never forgot James Hayes. And she made sure Ana never forgot either. An American soldier delivered you, Rosa would say, showing her daughter the photograph Hayes had sent in 1947. Him in civilian clothes, standing with Sarah and their newborn son in a foxhole while the war tried to kill us. He saved our lives.

Ana grew up with that story, carried it. When she had her own children, she told them. When they had children, she told them, too. Hayes returned to Wisconsin, became a registered nurse, had three children with Sarah, built a good life. But the forest returned with him in nightmares. Sarah would find him awake at 3:00 a.m. turning his wedding ring, counting breaths, the screams, the blood, the boys he could not save.

But every November 23rd, he would write to Rosa. And somehow knowing Ana was alive made the nightmares quieter. In 2004, at age 60, Anya decided to find the man who delivered her. It took 6 months of research, letters to the US Veterans Administration, emails to Wisconsin Historical Societies, dead ends, and false leads, but eventually an address, a phone number, and on the other end of the line, a voice she had never heard, but somehow recognized. Mr. Hayes.

James Hayes, who served as a combat medic in the Herkin Forest. Yes, said the 82year-old man, cautious. Who is calling? My name is Anja Jameson Becker. You delivered me in a foxhole in November 1944. Silence long enough that Ana thought the line had disconnected. Then Ana, yes, you’re alive. You are.

How old are you now? 60. I have three children, eight grandchildren, and none of us would exist without you. Another silence, then the sound of crying. An old man crying. I have thought about you, Hayes whispered. So many times. Wondered if you survived, if you had a good life. I did because of you. Anja took a breath. Mr.

Hayes, my family would like to meet you. All of us. Would that be possible? It took three months to arrange. Hayes’s health was not perfect heart trouble, arthritis, but he was mobile, sharp, excited in a way he had not felt in years. They met at a park in Wisconsin. Summer, warm, perfect. Hayes sat on a bench, Sarah beside him, their own children and grandchildren nearby.

And then they arrived. Anja, gay-haired and beautiful, walking toward him with an army behind her. 11 people, three generations, all because of 90 minutes in a foxhole 60 years ago. Ana reached him first. Mr. Hayes, he stood shaky and looked at her face, saw Rose’s features, saw the baby he had caught in his hands, now a grandmother herself.

Anja, he said, you are here. You are real. I am here. She took his hands. And I want you to meet everyone who exists because you chose compassion. She turned to the crowd behind her. Children, grandchildren, this is James Hayes. The man who delivered me in a war zone. The man who saved my mother. The man who proved that even in darkness, humans can choose light. The families merged.

Children met children. Grandchildren played together. Hayes held Ana’s youngest grandchild, a boy 3 years old named James, and wept openly. I have thought about you so many times, he told Ana. Every November 23rd, I would remember. Wonder where you were. Hope you were okay. I was more than okay. Ana said, “I was loved. I had opportunities.

I lived.” She gestured at her family. And I made sure all of them knew that their existence started with an act of kindness. That the enemy, what we called the enemy, was capable of extraordinary humanity. Hayes looked at her family, at the children laughing at the evidence of life continuing, branching, growing from that single moment in 1944.

I just did what anyone would do. No, Anja said firmly. You did what you chose to do and that choice echoed forward through decades, through generations, through all of us. They spent the afternoon together, shared stories. Hayes told them about the war, about the terror, about the moments he questioned everything.

Ana told them about growing up in post-war Germany, about her mother’s stories, about learning that Americans were not monsters, but people complicated, flawed, capable of grace. As the sun set, Anja pulled Hayes aside. “My mother died in 1998,” she said quietly. “But before she passed, she made me promise something.” “What?” “To find you.

To bring my family to meet you. To say the words she never got to say properly.” Ana’s voice broke. “Thank you. Not just for delivering me, for seeing her. for treating her like a human being when the world said she was just an enemy. For proving that kindness is not erased by war. Hayes pulled her into a hug.

This woman he had brought into the world. This life that had started in chaos and survived to create beauty. Your mother was brave, he whispered. And so are you, they stayed in contact. Hayes died in 2009 peacefully surrounded by family. Anya attended his funeral. gave a eulogy that made hardened veterans cry. “James Hayes delivered me in a foxhole,” she said.

“But he delivered something else, too. A lesson. That our worst moments can produce our greatest humanity. That the labels we use enemy, friend, American, German, matter less than the choices we make. That one act of compassion can ripple forward through time, creating lives, creating futures, creating hope.

” She approached his casket, hand trembling on the polished wood. Thank you, James, for my first breath and for teaching me how to live afterward. Today, Ana is 80 years old. She speaks to schools across Germany about her birth story, about the American medic who proved that enemies are made, not born.

About the war that tried to destroy everything but could not destroy human decency. She carries a photograph Hayes in 1945, young and tired, holding a bundled baby in a foxhole. On the back, in faded ink, Hayes wrote, “Anga Jameson Becker, born November 23rd, 1944. Proof that life finds a way.” In her wallet, she carries another photo, her 11 family members with Hayes in Wisconsin, 2004.

Proof that the life that found a way kept growing. And when young people ask her, as they always do, what lesson they should take from her story, she tells them, “Look at the person your world calls enemy.” Really, look. Are they truly your enemy? Or are they someone’s Rosa, someone’s haze, caught in systems bigger than themselves? She pauses, lets that sink in.

Because somewhere, right now, in some war, some conflict, some divide, there is a foxhole waiting and two people who think they are enemies and a choice. Choose compassion. Choose to see the human. Choose what James Hayes chose because that choice, that one choice can echo forward forever. If this story moved you, share it.

Not for me, for the Rosa Beckers and James Hes still out there choosing compassion in impossible moments. And if you want more untold stories from World War stories about ordinary people making extraordinary choices, please subscribe, like, and share our channel. Because these voices deserve to echo forward. These stories deserve to live.

Thanks for watching. I hope this honest and emotional moment from wartime touched you. Don’t forget to like, share, and subscribe for more true stories from