Across the ruins of Europe, church bells rang, rifles fired into the air, and banners proclaimed a day of liberation. For millions, it was the end of six years of total war. But for a certain group of young women standing in the shadows of German railway yards, this day meant something very different.

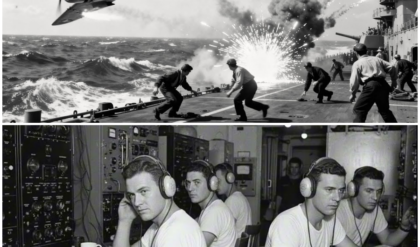

Their uniforms were threadbear remnants of the weremocked auxiliaries, the halerinan, their boots cracked, their hair unwashed after weeks of retreat. Some were barely 20, their faces still holding the remnants of youth beneath layers of soot and fatigue. They were secretaries, typists, radio operators, nurses, cogs in a military machine that had devoured their country and then collapsed in their hand.

Now with the Reich broken, they were herded into trains not for homecoming, but for captivity. The image was strange. lines of women in gray green skirts and jackets, dragging battered suitcases, stepping into the dark wooden box cars that had once fed troops to the front. Some clutched rosaries, others rationed tins, some nothing at all.

A girl from Hamburg whispered to her companion, “The Americans will not spare us. They will make examples.” She had heard it from a Luwaffa officer during the chaos of surrender. Another taller, hardened by years of manning anti-aircraft search lights, said nothing, but her jaw was set as if bracing for a blow. They had been told again and again that the Allies, especially the Americans, were not men, but wolves, that captivity would mean degradation, cruelty, perhaps worse. The trains rumbled westward through a landscape of ruins. Charred towns drifted past like ghosts. Churches

without steeples, bridges folded into rivers, skeletal factories where smoke still smoldered. Children waved from embankments, their faces thin as paper. At night, when the train stopped, the women huddled against one another for warmth, listening to the guards boots outside and the occasional crack of gunfire in the distance.

One woman, Anna, a former secretary from Munich, wrote in a small diary she had managed to keep. We are being taken far. None knows where. My mother will think I am dead. Perhaps I will be. The journey ended not in a German camp, but in the chaos of occupied ports, Bremen, Lohav, Sherborg, where ships waited under American flags.

The women were marched to the gangways, past soldiers who watched them with expressions they could not read. Some looked curious, others indifferent. The women had expected snarls, insults, blows. Instead, there was order, paperwork, lines. They were counted, tagged, divided into group. It felt more like a strange bureaucracy than vengeance.

Still, as the ship’s engines grown to life, and the coastline of Europe shrank, dread settled into their bones. The Atlantic stretched wide and endless, and America, mysterious, distant, a land of myth and enemy caricature, waited on the other side. On board, seasickness gripped many. The bunks were stacked in steel holds, the air thick with salt and diesel.

Food was issued on trays, pale bread, slabs of meat, steaming mugs of coffee. The women stared in disbelief. For years they had eaten cabbage stalks, heirzats bread made of sawdust and barley, watery soup ladled from rusted cans. Some hesitated to eat suspecting poison. Others devoured it, tears rolling down their faces at the taste of real bread.

“They feed us like they feed themselves,” whispered one, astonished. It was not kindness they expected. It was punishment. Yet here was a different reality, and it unsettled them more than cruelty might have. When at last the ships reached American shores, New York, Boston, New Orleans, the women gathered on deck, clutching the rails, gazing at skylines rising untouched by bombs.

The Statue of Liberty loomed, an irony that drew no smiles. Crowds lined the peers, some jeering, some merely watching. The women were marched ashore undergard, their boots echoing on wooden plank. The air smelled different, cleaner, freer, salted by the ocean, but untainted by the ash of war.

For the first time, some realized how completely their world had collapsed. Germany was rubble. America was intact, prosperous, alive. Buses and trains carried them inland to camps built across the United States, Fort Ogulthorp in Georgia, Camp Rustin in Louisiana, and dozens more. The roads unfurled before them, flanked by green fields and towns where children rode bicycles and houses gleamed with white porches.

To women who had watched their own cities burn under Allied bombs, the sight was almost incomprehensible. They whispered among themselves. Was this truly the land of the monsters? Could this abundance be real? The Reich had promised victory and delivered ruins.

The enemy they had been taught to hate seemed to live in another universe altogether. At the gates of the camps, their names were recorded, possessions cataloged, uniforms exchanged for plain work closed. But before they could settle, there was one more step. The guards, firm but not brutal, directed them toward a building. Inside, steam hissed and water drip. It was the delousing station, though the women did not yet know. Their hearts pounded.

This could be humiliation, degradation, the cruelty they had been warned about. In the long line, whispers circled. This is where they will make us suffer. One clutched her suitcase as if it were a shield. Another crossed herself silently.

The line moved slowly, and as each woman entered the tiled room, her expectations collided with reality. They were handed bars of soap, real soap, thick, white, heavy in the hand, smelling faintly of flowers. Towels followed, then clean garments. The showers released streams of hot water, washing away months of grime. Some women wept openly, the sound echoing off the tiles.

Others laughed nervously, unable to believe it. For the first time in years, they felt clean, their hair free of lice, their skin freed of dirt. It was not humiliation, but restoration, and it shook them to the core. Anna wrote again in her diary that night, her handwriting trembling across the page.

We were told we would be beaten, mocked, broken. Instead, we were given soap. How can this be? She did not yet know that this moment, the simple act of washing, would remain etched in memory longer than the war itself. The women lay in bunks that night, hair still damp from the showers, wrapped in blankets that smelled faintly of starch and cotton.

Outside the American knight hummed with crickets, far from the thunder of guns. They whispered to one another, their voices low but urgent, as if sharing a secret too fragile to be spoken aloud. Perhaps the enemy was not what they had been told.

Perhaps there was something here that neither propaganda nor fear could explain. What awaited them in the days to come. Food, work, encounters with Americans would astonish them even further. For now, though one image lingered in every mind, the soap in their hands, slippery, fragrant, absurdly gentle. It was only the beginning of their captivity. Yet it already felt like the beginning of something else.

And as dawn broke over the camp, a question settled among them like morning mist. If the enemy could show such unexpected humanity, what other surprises lay ahead? The buses rolled through gates crowned with barbed wire, their engines grumbling as dust rose in pale clouds across the camp road.

To the women inside, the sight was at once frightening and strangely orderly. Guard towers stood at intervals. Soldiers lounged with rifles slung casually and rows of barracks stretched neatly across the fields. This was not the gray brutality of a concentration camp. This was something bewilderingly different. The wooden buildings were painted, the paths swept, the fences intact but not menacing.

The prisoners looked at one another, sharing silent glances that asked the same question. What world have we stepped into? When they were filed off the bus, each woman was handed a numbered tag. American officers moved with clipped efficiency, scribbling notes, stamping documents.

The women stiffened, bracing for insults or harsh orders. Yet the guards spoke with calmness, their English tones softened by southern draws or Midwestern flatness. For many, the first shock came not from cruelty, but from indifference. The Americans treated them not as monsters, nor as guests, but as something strangely ordinary, prisoners of war to be managed, cataloged, and housed.

The delousing station had already unsettled them with its unexpected civility, but what followed was stranger still. After the showers, they were led into a mess hall. The long room smelled of coffee, fresh bread, and something frying in grease. The women froze in the doorway, disoriented by the smell alone. Tables stretched across the hall, laden with trays of food.

Boiled potatoes, carrots, beef stew, soft rolls gleaming with butter. Steam fogged the windows. The aroma was thick and overwhelming. An assault of abundance. One of the guards motioned them forward. Reluctantly, they stepped to the counter. A cook in a white apron dropped spoonfuls of stew onto tin plates. slid slices of bread across, filled mugs with coffee.

The women accepted the trays as though handling explosive. Some could not meet the cook’s eye. Others stared at the food, unsure if it was real. In Germany, the final winter of war had reduced meals to black bread made with sawdust, watery turnip soup, perhaps a scrap of horse meat, if one was lucky.

Now in the enemy’s camp, they were given more in one meal than they had seen in week. Anna diary tucked safely under her mattress, sat with her tray at the long table. She dipped her spoon into the stew, watching the grease float on top, the chunks of meat glistening. Tentatively she tasted it. Her eyes widened, and she pressed a hand to her mouth as though ashamed.

Around her, other women hesitated, then ate in silence, broken only by the scrape of cutlery. For some, tears slid down their cheeks. One whispered, “My brothers starved in the snow, and here they feed us like this.” It was not kindness they had been promised by their own leaders, but humiliation. And yet the humiliation never came. There were no taunts, no jeering.

The guards paced slowly up and down, glancing at them with professional detachment. One young soldier, hardly older than the women themselves, even gave a crooked smile as he passed, as if to reassure them. The prisoners were unprepared for such contradictions. They had stealed themselves for cruelty, but this quiet civility was somehow more disturbing. In the days that followed, life in the camp revealed further shock.

Each morning they were woken by a bell, issued breakfast, and assigned light duties. Some worked in kitchens, others in fields nearby, some inreries where American uniforms were scrubbed and pressed. They were paid small wages in camp script. currency that could be used to buy items at the canteen.

There on wooden shelves lay chocolates, cigarettes, pencils, even lipstick. The women stood before these goods as though at an altar. A bar of chocolate was a miracle. A tube of lipstick unthinkable. And yet here the enemy offered it in exchange for work. The irony was almost cruel. Back in Germany, their families scavenged for scrap.

Cities lay in ashes. Children picked through rubble for crust. Letters trickled in from home, if they arrived at all, filled with despair. One woman read aloud by candlelight, “We live in the cellar now, the house above destroyed. We boil weeds for soup. If you have anything, send it.

” She folded the paper with trembling fingers, knowing she could not send food back, only words. The gulf between their suffering homeland and the strange abundance of the camp widened with each passing day. Some began to feel shame heavier than chains. They were enemies, yet here they were fed, clothed, sheltered.

The Reich had demanded their loyalty, sent them to man radios and spotlights, but gave them hunger and ruins in return. America, the sworn enemy, gave them soap and stew. This inversion noded at their souls, unspoken but ever present. At night they lay awake, listening to the crickets outside the barracks and wondering what it meant. Not all adjusted easily. A few resisted, refusing to eat, hoarding bread crusts under pillows, convinced the generosity was a trick.

Rumors spread that the food might be drugged, that the soap contained some hidden poison. Yet day after day, nothing happened except the quiet routine of camp life. The body fattened, the skin cleared, the lice vanished. Slowly, suspicion yielded to reluctant acceptance. The Americans, too, watched with curiosity.

Many guards had never seen German women before, only caricatures in propaganda. They were surprised to find them thin, exhausted, often frightened. Some were barely older than their sisters back home. One guard wrote in a letter, “They are not what we were told. They are girls and they look at us as if waiting for a blow that never comes.

” And so the conflict deepened, not one of guns and trenches, but of perception. The women were forced to reconcile the enemy they had imagined with the reality before them. Each bite of bread, each bar of soap, each neutral word from a guard cracked the image they had been taught to believe. The war had ended, but in their minds another battle began. A battle between memory and reality, propaganda and truth.

Anna captured it in her diary with painful clarity. To be treated with dignity by those we were told were beasts. It is harder than hatred. Hatred is easy. Dignity is unbearable. Her words spoke for many. The women no longer feared being broken by cruelty. They feared being undone by kindness.

One evening after work in the fields, the women were marched back to camp as the sun dipped low, spilling gold across the horizon. The sky was vast, unmarred by smoke, and the air smelled of cut grass. It was a simple scene, yet it weighed on them more than the ruins of their homeland. Here was a land untouched, abundant, alive. The Reich had collapsed into rubble. America stood and scathed.

And in that realization, a new unease took root. They had survived the first shock. The soap, the showers, the food. But something else was dawning, something more difficult to confront. For in the days ahead, it would not be physical survival that challenged them, but the slow, unsettling recognition that the enemy might be far more human and far more powerful than they had ever imagined.

The weeks settled into a rhythm, and in that rhythm, the women began to lose track of time. Morning bell, breakfast line, work detail, supper, lights out. Yet beneath the surface of routine, a strange transformation stirred. At first they had counted days like prisoners scratching tallies into stone, but gradually the sharp edge of captivity dulled, replaced by a quiet bewilderment.

They were captives, yes, but they were also fed, clothed, even paid for women raised in a collapsing Reich, where loyalty was rewarded with hunger. This inversion noded at their thoughts more persistently than any barbed wire fence. Anna, who had once sat in a Munich office typing orders she never questioned, now worked in the camp laundry.

The scent of starch and soap clung to her fingers as she scrubbed American uniforms smooth. Each shirt bore the initials of men who were her sworn enemies, and yet as she folded them neatly into piles, she felt less hatred than an odd guilty relief. Here was work that did not involve war, work that kept her alive.

Sometimes she caught her own reflection in the polished steel of the washing drums and wondered who she was becoming. Others were sent into the fields under guard, harvesting crops that fed both prisoners and soldiers. They felt the sun on their backs, the dirt under their nails, and the startling weight of full baskets. Some even laughed softly at their own sweat, finding in the labor a reminder of the villages they had left behind.

In the evenings they returned to the camp, their muscles aching, their spirits strangely lighter. This was not the degradation they had prepared themselves for. This was something else entirely. The camp canteen soon became the most bewildering corner of their new world.

With their wages, small slips of camp script, they could buy chocolate bars, cigarettes, even jars of jam. The first time Anna bit into a Hershey bar, the sweetness exploded on her tongue like nothing she had tasted since childhood. Tears pricricked her eyes and she turned away from the others, ashamed of her own joy.

A girl from Bremen smeared lipstick on her lips, staring at herself in a small mirror with disbelief. “I feel human again,” she murmured as though confessing a sin. But the abundance carried its own torment. Letters from home continued to arrive, smuggled through sensors, their words etched in desperation. Families wrote of bombed out apartments, of children coughing in sellers, of bread lines stretching into the cold. One woman read aloud her mother’s plea. If only we had your American bread.

Your brother starves around her. Silence fell heavy, broken only by the scratching of rats beneath the barracks floorboards. The women sat clutching their letters, their trays of food untouched, the shame of plenty burning in their throat. The Americans noticed the contradiction, too.

Some guards were surprised to see the German women gaining weight in captivity, cheeks filling, hair regaining its shine. “They’re better fed than folks back home in some towns,” one soldier muttered. Half in resentment, half in wonder. Yet rules were rules. Under the Geneva Convention, prisoners were to be treated according to standards that often exceeded those of war torn Europe. The irony was not lost on anyone.

Still, suspicion never fully vanished. At night, whispers crept through the bunks. What if this was all a facade? What if tomorrow the masks fell away and cruelty began? A handful clung to their distrust, hoarding crusts of bread under mattresses, convinced the abundance was a trap.

Yet, as weeks turned into months, even the most cautious were worn down by the relentless normality of American order. No beatings came, no punishments beyond the dull monotony of work. The greatest cruelty, it seemed, was to be treated decently. Anna’s diary recorded the conflict with painful clarity. I eat and my stomach thanks me. I sleep and my body grows strong.

Yet each kindness cuts me deeper. How do I reconcile this with the faces of children in Munich who drink water for supper? Her words gave shape to the invisible war now raging in many hearts. To be brutalized would have been easier. To be dignified by the enemy was unbearable. Amid this turmoil, small encounters with Americans deepened the contradictions.

One evening, a young guard dropped his flashlight during roll call. Anna stooped instinctively, picked it up, and handed it back. Their fingers brushed, and for an instant, their eyes met. He gave a quiet nod, nothing more, but the moment lingered in her mind for days. Another time, a soldier passing by the laundry hummed a tune, soft, rhythmic, unmistakably American.

A girl from Cologne recognized the melody, laughed, and began humming along. For a brief second, two enemies shared a song across a gulf that the war had declared unbridgegable. Not all guards were friendly. Some looked at the women with open disdain, their gazes sharp with grief for brothers lost in Europe.

Yet even their hostility rarely spilled into action. The women were not free, but neither were they brutalized. They existed in a liinal state, suspended between punishment and reprieve. It left them restless, uneasy, unable to anchor themselves in the certainty of hatred. And then came the day they were taken outside the wire for work detail in nearby towns.

The women rode in trucks through American streets, their eyes wide at shops displaying goods in full windows, children chasing hoops down sidewalks, men reading newspapers on porches untouched by bombs. They smelled the sweetness of bakeries, saw rows of cars gleaming in sunlight, watched movie posters plastered on brick walls.

To women whose last memories of Germany were cratered streets and charred ruins, the vision was overwhelming. America was not only intact, it was flourishing. That night, back in camp, the barracks buzzed with whispers. Did you see the cars? The bread? It was white. the houses untouched. For some, the shock of America’s abundance was intoxicating. For others, it was unbearable proof of Germany’s collapse.

The Reich that had promised them empire had left only ruins. The enemy had delivered the world of plenty. It was a truth too large to swallow, too sharp to ignore. The conflict, once external, now turned inward. In their hearts, loyalty battled with reality, pride with gratitude, hatred with reluctant admiration. It was not a clash of armies, but a slow erosion of belief.

Each bar of chocolate, each hot shower, each glimpse of an unbroken American street chipped away at the fortress of propaganda. The women began to realize that the Reich had not only lied, it had stolen their vision of the world itself. As the crickets sang outside the wire and the camp lights glowed like pale moons, Anna lay awake staring at the rafters.

She thought of her family in Munich, of her mother boiling weeds for supper, of the rubble where her office once stood. She thought two of the American guards nod, the chocolate melting on her tongue, the clean water streaming down her back. Between these images stretched an abyss she could not yet cross. But in her heart she knew that something within her was shifting, something irreversible.

And as another dawn broke over the camp, gilding the barbed wire in gold, the women understood that survival was no longer the only question. The real challenge lay in confronting what their captivity revealed about the enemy, about their homeland, and about themselves. Autumn leaves drifted across the campyard, crisp and golden in the breeze.

The season had turned, though time inside the wire felt strangely fluid, its passage marked less by calendars than by the rhythm of meals, work, and letters from home. Yet beneath the routine, something profound had taken root. For months the women had lived with the shock of survival in America, their days filled with soap, bread, and baffling civility.

But now came the harder reckoning, what all of this meant for who they had been and who they might become. Anna sat on the barack steps one evening, diary balanced on her knees. She wrote by the fading light, her words sharper than before, as though she could no longer contain the conflict churning within.

I have eaten more in captivity than in all the winters of the Reich. I have slept without fear of bombs, and yet my heart is not at peace. What kind of world is it where the enemy shows more dignity than our own?” Her handwriting trembled. She paused, hearing laughter from a nearby group of women.

They were trading pieces of candy, teasing one another about lipstick shades, voices bright as though the war had never touched them. Anna envied them, but she could not join them. Her loyalty to her broken homeland weighed too heavily, even as it slipped through her fingers. The Americans, for their part, grew accustomed to their unlikely prisoners.

Some guards stopped seeing them as symbols of an enemy regime and began to recognize them as individuals, frail, stubborn, bewildered, sometimes even charming in their awkward English attempts. A few guards shared cigarettes, passing them silently across the wire, a gesture more human than political. But for every act of quiet kindness, there remained a distance.

These were still the enemy, still prisoners, still reminders of lives lost overseas. The camp was never free of tension, only softened by routine. It was outside the wire, however, that the greatest revelations came. More frequently now, women were sent into American towns for labor, under escort, but with more freedom than they had imagined possible.

They picked cotton in fields, worked in caneries, or tidied municipal parks. Towns folk watched them with curiosity. Sometimes cold, sometimes warm, sometimes indifferent. Children galked openly, pointing at the German girls, while shopkeepers peered from doorways. Yet what struck the women most was not hostility but normaly. American life flowed unbroken. Cinemas lit their mares. Grocery stores displayed overflowing shelves.

Radios blared jazz and baseball scores. Four women from cities where rubble had replaced boulevards. The site was almost unbearable. One day, after hours of harvesting, Anna’s group was given lunch in a church hall by local volunteers. The tables groaned with sandwiches, fruit, pies. The women hesitated, hands hovering as if afraid the food might vanish.

An elderly American woman, flower dusting her apron, urged them gently, “Eat, eat.” Anna bit into an apple, crisp and sweet, and nearly wept. She had not tasted fruit since 1942. Across the table, another prisoner whispered, “This is paradise.” But Anna only stared at the apple’s white flesh. Hearing her mother’s voice in memory, “Save the peel for soup.

” The contrast nearly broke her. At night, back in the barracks, conversations grew heavier. They spoke of home, of families surviving in cellars, of children barefoot in the snow, of brothers lost to the eastern front. Some began to admit aloud what had long been unspeakable, that perhaps their nation had lied to them, had sacrificed them not for glory, but for destruction.

We were taught they were beasts, murmured one woman, staring into her blanket. But who are the beasts now? those who bombed our homes or those who built this world of plenty. No one answered. Silence carried more weight than words. Yet guilt was not the only burden. Gratitude too unsettled them. They were prisoners, but they were alive, clean, fed.

They had expected to be stripped of dignity. Yet they had been given more than they dared imagine. The soap, the showers, the chocolate, all were tokens of something larger, something harder to name. Was it mercy? Was it hypocrisy? Or was it simply that the Americans lived by rules the Reich had long abandoned? Each woman wrestled with the questions alone, unable to resolve them, but unable to turn away.

Anna’s diary grew into a confession of this turmoil. It would be easier to hate. Hatred is a fortress. It keeps the world out. But what they give us, bread, soap, music, it slips past the walls. It demands we see them as human. And if they are human, then what becomes of all the blood, all the ruins, all the lies we swallowed.

She closed the book one evening, unable to write more. Her chest tight with something like betrayal. The guards too sensed the shift. They watched their prisoners laugh at American films shown in makeshift camp cinemas, saw them sing along clumsily but earnestly to songs on the radio. It was disarming, unsettling.

One sergeant remarked to another, “You’d forget for a minute they were the enemy if you didn’t look at the uniforms.” The comment carried a warning as much as wonder. War had demanded clear lines. Life blurred them. The greatest shock, however, lay not in food or work or glimpses of American streets, but in the mirror. The women’s bodies changed.

Their faces filled out. Hair regained its luster. color returned to cheek. Some even looked younger, as though captivity had peeled away years of war. To see themselves restored in this way was almost unbearable. It forced them to recognize how deeply the Reich had failed them. The enemy had made them healthy.

Their own nation had made them starve. It was not just a revelation, but an indictment. And yet, even as they adjusted, even as laughter returned, an unease hung over everything, for they knew captivity could not last forever. One day they would be sent home to Germany to rubble, to families waiting in despair.

The thought of leaving abundance for hunger again, of trading soap for soot, filled them with dread. More than one whispered at night, “I am afraid to go back.” It was treasonous to admit, but true. As winter neared, rumors spread of impending transfers, of repatriation, of journeys eastward. The whispers filled the barracks with unease.

What awaited them in the ruins of their homeland? Would their families even recognize them, well-fed, clean, cheeks glowing with the health of captivity? Some dreaded the judgment in their mother’s eyes, the silent accusation that they had lived well while others starve. Anna, staring once more at her diary, wrote the words she had never dared before. I fear leaving more than I feared arriving.

The confession chilled her, but it was honest, for the enemy’s greatest weapon had not been guns or bombs. It had been soap, food, and dignity. And those things had done what hatred could not. They had changed her. One morning, as Frost laced the camp fences, the announcement came. A transport would depart soon.

The women crowded together, hearts pounding, eyes wide with questions they could not voice. To return meant facing hunger, ruins, and the ghosts of all they had believed. To stay meant captivity, but also life. The guards read the names from a list, their voices flat. But to the women, every syllable landed like a thunderclap. And as Anna heard her name called, as she stepped forward into the cold morning light, she realized the true conflict was no longer between nations.

It was inside her in the space where hatred had once lived and where something new, fragile, dangerous, undeniable had begun to