The dustcovered box had been in my grandmother’s attic for decades. Just old family photographs, she’d always said, never showing much interest in its contents. But after her passing last month, the responsibility of sorting through her belongings fell to me.

The house itself was a Victorian masterpiece built in 1890 with gabled roofs, ornate woodwork, and secrets tucked away in every corner. My grandmother had lived there for over 60 years, collecting memories like others collect fine china. It was a rainy Tuesday afternoon when I found the box tucked away beneath a pile of faded curtains and forgotten Christmas decorations.

The attic smelled of cedar and thyme, dust moes dancing in the slanted beams of light that filtered through the small dormer window. The floorboards creaked beneath my weight as I moved across the space, pulling the string of the single light bulb that hung from the rafters. The box itself was unremarkable. Cardboard with reinforced corners that had begun to fray.

The word photographs written across the top in my grandfather’s precise penmanship. I settled onto an old trunk, brushing away the dust and gently opening the box. The photographs inside were mostly what you’d expect. Stern-faced ancestors in formal attire. Family gatherings where no one smiled. Children posed awkwardly in their Sunday best.

typical remnants of the late 19th and early 20th centuries when photography was still a special occasion requiring serious expressions and your finest clothes. I sorted through them methodically, creating piles, identified relatives, unknown faces, landscapes, and buildings. Most were mounted on thick cardboard, their edges softened with age. Some had names and dates carefully inscribed on the back.

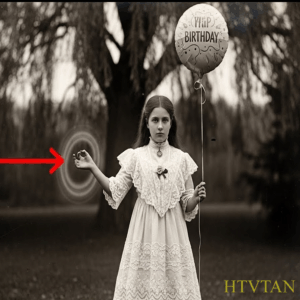

Others remained anonymous, their subjects identities lost to time. But one photograph caught my eye immediately, practically jumping out from the stack. A small girl, perhaps 5 or 6 years old, stood alone in what appeared to be a garden. The photograph was remarkably clear for its age, each detail rendered with precision that spoke to the skill of the photographer.

Her dress was pristine white with intricate lace work and a satin ribbon tied around her waist, the kind of expensive garment that would have been reserved for special occasions in that era. Her hair was arranged in perfect ringlets, and a bow was fastened carefully on the side of her head.

In her right hand, she clutched the string of a balloon, a birthday balloon, judging by the occasion captured in the photograph. What made this photograph peculiar was not just the balloon, which would have been quite a luxury in 1902 when the photograph was dated. No, what drew my attention was the girl’s left hand. It was extended outward, her small fingers clearly wrapped around something, or rather someone else’s hand, but there was no one there, just empty space where another person should have been standing.

I held the photograph closer to the light, examining it from different angles. The girl’s fingers were definitely curled, as if holding on to another hand. The positioning was unmistakable. Yet the space beside her was completely empty, not blurred or faded, just vacant, as though someone had been carefully edited out of the image. But this was 1902.

Such photographic manipulation would have been extraordinarily difficult, if not impossible. I turned the photograph over. In fading ink, someone had written Elizabeth Caldwell, 6th birthday, June 17th, 1902. Below that, in a different hand, almost too faint to read. The willow garden. That was all. No mention of the invisible handholder.

I set the photograph aside, intrigued, but not particularly disturbed. Old photographs often contained oddities, strange shadows, blurs from movement during long exposure times, double exposures creating ghostly apparitions. This was likely just another photographic curiosity, a trick of the light, or a flaw in the development process.

At least that’s what I told myself as I continued sorting through the box, occasionally glancing back at the image of Elizabeth Caldwell and her phantom companion. Outside, rain pattered against the attic window, creating a soothing rhythm as afternoon faded into evening.

I found myself returning to that photograph repeatedly, studying the girl’s face, her posture, the way her fingers curled around invisible ones. There was something compelling about her expression. Not the serious, stiff pose common in photography of that era, but a genuine smile, her eyes bright with what appeared to be delight.

“Who were you looking at, Elizabeth?” I murmured, tracing the outline of the empty space beside her. “Who was holding your hand?” 2 weeks later, I’d nearly forgotten about the strange photograph. I was organizing the last of my grandmother’s possessions in the parlor, boxing books, and sorting through drawers of papers, when I came across a small leatherbound journal tucked behind a row of first edition novels in the cherrywood bookcase.

It was unassuming, its brown leather cover worn smooth at the corners, a simple ribbon bookmark protruding from its pages. The spine cracked as I opened it, suggesting it hadn’t been read in many years. The handwriting inside was delicate, precise. My great-grandmother Martha’s according to the inscription on the first page, the private journal of Martha Winters Caldwell, begun January 1st, 1900. My heart quickened.

Caldwell, the same surname as the girl in the photograph. Martha would have been Elizabeth’s mother. I flipped through casually at first, reading snippets about daily life in the early 1900s. Martha wrote about household duties, social calls, her husband’s work at the bank. She mentioned Elizabeth frequently, her progress with piano lessons, her preference for climbing trees over playing with dolls, her quick mind that sometimes led to impertinent questions, ordinary musings of a mother chronicling her daughter’s childhood, until I reached an entry dated June

18th, 1902, the day after Elizabeth’s birthday. Yesterday was Elizabeth’s 6th birthday celebration. The weather was mercifully cool for June, allowing us to have her small party in the garden as she had so wished. Mrs.

Holloway prepared a splendid lunchon, and the children played lawn games until nearly 4:00. The photographer, Mr. Winters, came to take her portrait in the garden. She was so pleased with the balloon Thomas brought home. I’ve never seen such delight in a child’s eyes. The other children were quite envious, which I fear Thomas rather enjoyed. He does spoil her. So, but something strange happened during the photography session. After the group portraits were completed and Mr.

Winter’s assistant was taking Elizabeth’s individual portrait, she kept speaking to someone none of us could see. She’s holding my hand, Elizabeth said, pointing to her left side. She says she’s my friend. When I asked who she was speaking about, Elizabeth simply smiled and said, “The girl who lives in the willow tree.” Mister Winters thought it charming.

A child’s imagination at play. I am not so certain. There was something in Elizabeth’s manner that unsettled me. She was not pretending. She truly saw someone there. Thomas says I am being fanciful. That it is merely a phase. Perhaps he is right. Children do have imaginary companions after all. But I cannot shake the feeling that there was something peculiar in the air yesterday.

A heaviness that descended over the garden during the photography session. Even Mrs. Holloway remarked upon it, though she attributed it to the approaching storm. I felt a chill run through me. I retrieved the photograph again from the box I’d brought downstairs, studying it more closely. The girl, Elizabeth, looked happy, her smile genuine, not forced like most children in photographs of that era, who had to hold still for uncomfortably long exposures. And her left hand, it wasn’t just positioned oddly.

Her fingers were clearly curled around something invisible. The next several entries in Martha’s journal made no mention of Elizabeth’s invisible friend. They returned to mundane matters, preserving summer fruits, a new hat purchased in town, concerns about Thomas’s persistent cough, planning for the church bizaar in August.

Then on July 3rd, Elizabeth has been speaking to her invisible friend more frequently. She calls her Margaret now and insists that Margaret joins us for meals. I’ve begun setting an extra place at the table to humor her, though Thomas was quite cross when he discovered my indulgence. He thinks I’m encouraging unhealthy fancies, but it seems to bring Elizabeth such joy.

Still, I cannot help but feel uneasy when I find Elizabeth having animated conversations with empty air, or when toys move from where I’ve placed them. Elizabeth’s doll was found in the garden this morning, though I am certain it was on her bed when I tucked her in last night.

Thomas says it is just Elizabeth being mischievous, but I’m not so certain. There is something in her eyes when she speaks of Margaret, a knowing beyond her years. I continued reading, my unease growing with each entry. Martha’s elegant script remained steady, but her words betrayed increasing concern. July 17th, 1902. Elizabeth woke screaming last night.

When I rushed to her room, she was sitting upright in bed, pointing at the corner, her face white with terror. Margaret is angry, she cried. She says, “I broke my promise.” I could see nothing in the darkness, but the room was ice cold despite the summer heat. Mrs. Holloway brought warm milk with a touch of brandy, which eventually calmed her.

When I asked what promise Elizabeth had made to Margaret, she wouldn’t say. She finally fell back asleep, clutching my hand, but not before whispering. “Margaret doesn’t like it when I have other friends.” I sat beside her bed until dawn, unable to shake the feeling that we were not alone in that room. July 30th, 1902.

I found Elizabeth’s favorite doll with its head twisted completely backward this morning. Elizabeth insisted that Margaret did it because the doll took too much of Elizabeth’s attention. I am truly concerned now. Thomas continues to dismiss my worries, saying that Elizabeth herself likely damaged the doll and is blaming her imaginary friend, but I saw the look in her eyes. She was frightened.

Whatever game this started as, I fear it has taken a troubling turn. I have written to my cousin Emily, whose husband is a physician specializing in nervous disorders in children. Perhaps he might advise us. August 8th, 1902. Thomas finally agrees something is wrong. Last night, as we sat in the parlor after Elizabeth had gone to bed, we both distinctly heard footsteps running up and down the hallway.

Though Elizabeth was fast asleep in her bed when we checked, Thomas suggested it might be mice in the walls. But mice do not create the sound of a child’s laughter. Nor do they leave wet footprints on the floor. Small like a child’s, but neither Elizabeth nor her shoes were wet. When confronted with this evidence, even Thomas could not maintain his skepticism.

He has agreed to speak with Reverend Collins about the possibility of blessing the house. August 15th, 1902. Elizabeth has fallen ill. Dr. Patterson says it is just a summer fever, but I fear it may be something more. She is so pale and she speaks constantly of Margaret now. Even in her delirium, she wants me to go with her.

Elizabeth keeps saying to the willow tree. She has something important to show me there. I’ve taken to sleeping in her room, afraid to leave her alone. The air feels thick with something I cannot name. Thomas has postponed his business trip to Boston, though he will not admit it is due to our concerns about Elizabeth. Mrs.

Holloway has begun leaving small dishes of salt in the corners of the rooms and hanging sprigs of herbs above the doorways. When Thomas questioned her, she merely said, “Old country practices, sir. Can’t hurt. Might help.” The entries continued, each more disturbing than the last. Elizabeth’s condition worsened. The strange occurrences in the house increased. Objects moving, doors slamming, the sound of a child’s laughter when no child was present.

Martha wrote of cold spots in the house, of Elizabeth’s toys rearranging themselves overnight, of the gardener refusing to work near the old willow tree because he claimed to see a child watching him from its branches. Then came the entry from August 20th, 1902. I dozed briefly in the chair beside Elizabeth’s bed this afternoon. The heat has been oppressive, and I had been awake most of the night.

When I opened my eyes, Elizabeth was gone from her bed. The whole household searched frantically. Thomas checking the road and neighboring properties. Mrs. Holloway and I searching every room of the house. The gardener examining the outuildings.

It was the stable boy, young Henry, who found her by the old willow tree at the far end of the garden. She was lying on the ground beneath its branches, unconscious, her night gown soiled with dirt, her feet wet as though she had been standing in water, though the ground was dry. We carried her back to the house where Dr. Patterson examined her thoroughly.

He could find no physical reason for her collapse, attributing it to her ongoing fever. When she finally woke, her eyes were different somehow. Older knowing, she said only. Margaret showed me where she died. Thomas wanted to dismiss it as fever dreams, but I saw the conviction in Elizabeth’s eyes. Under the willow tree, she insisted, her voice stronger than it had been in days.

Margaret’s bones are there. She wants someone to find them so she can rest. Thomas forbade any further discussion, but I saw him walking toward the willow tree after dinner, his expression troubled. My hands were shaking now. I knew the willow tree Martha mentioned, or rather, I knew where it had stood.

My grandmother had shown me the stump years ago, explaining that the massive old tree had been cut down in the 1950s after disease hollowed its trunk. It had stood near a small decorative pond that had long since been filled in at the farthest corner of what had once been the Caldwell property. August 22nd, 1902. Thomas hired men to dig beneath the willow tree today. I thought him mad, but after what Elizabeth said, we had to know.

The men worked from dawn, removing the stones that bordered the small pond, then digging into the soft earth beneath. At first they found nothing but soil and roots. Thomas was about to call a halt to the endeavor when one of the men’s shovels struck something that was neither stone nor root. God help us.

They found bones, small bones, a child’s bones, and scraps of fabric that might once have been a dress. The sheriff has been summoned. Thomas is in his study with a glass of brandy, his hands shaking so badly he can barely hold it. Elizabeth strangely seems improved. Her fever has broken, and she sits by her window, humming softly to herself.

When I asked her about Margaret, she smiled and said she’s still here, but she’s not angry anymore. She just wanted someone to find her. August 25th, 1902. The remains have been identified as those of Margaret Winters, daughter of the photographer who took Elizabeth’s birthday portrait. The child went missing in 1897, 5 years ago. She would have been about Elizabeth’s age now.

They’re saying she must have drowned in the pond and someone buried her beneath the willow. Mr. Harold Winters was summoned to identify the clothing and a small silver bracelet found with the remains. He collapsed when told had to be revived with smelling salts.

His poor wife had died of grief 2 years after Margaret’s disappearance, never knowing what had become of their daughter. And to think he was in our garden taking photographs, not knowing his daughter lay buried just yards away, how could anyone have known? But Elizabeth knew. Somehow Elizabeth knew. Sheriff Collins has opened an investigation into the child’s death.

Margaret’s remains will be properly buried in the churchyard next week. Thomas has insisted our family attend the service, though I fear it will be too distressing for Elizabeth. The entries that followed documented the investigation. The pond had been drained completely. The sheriff questioned everyone in the household and neighborhood.

No one could determine how Margaret Winters had ended up buried beneath the willow tree or how Elizabeth had known she was there. September 10th, 1902. Elizabeth seems much recovered now. Her fever is gone and she speaks less of Margaret. When she does mention her, it’s to say that Margaret is at rest now and not angry anymore.

I’ve asked Elizabeth how she knew about the little girl under the tree, but she only says, “She showed me in my dreams. I cannot make sense of it, but I am grateful that my daughter seems to be returning to herself. She has begun piano lessons again and has asked to invite her friend Sarah for tea next week.

The first time she has shown interest in her living friend since before her birthday. I continued reading, but the journal entries gradually returned to normal life. Elizabeth recovered fully. The winter’s case remained unsolved. Martha mentioned occasionally finding Elizabeth speaking to thin air, but these instances became less frequent as months passed.

The last mention of Margaret came in an entry from June 17th, 1903. Elizabeth’s 7th birthday today. One year since the photograph with the balloon. One year since Margaret first appeared, we had a small celebration, quieter than last year’s.

Thomas thought it best to avoid too much excitement given all that has happened. Elizabeth insisted on visiting the willow tree after her party. She placed a small bouquet of wild flowers on the spot where Margaret was found. She’s still here sometimes, Elizabeth told me. But she’s happier now that people know her name. I pray that is true for all our sakes. Thomas wants us to travel to Europe next summer.

Says a change of scenery will do us all good. Perhaps he is right. I closed the journal, my mind racing. Could this possibly be true? A child’s ghost reaching out from beyond the grave, visible only in a photograph and to another child who shared her age. I pulled out my phone and searched for information about Margaret Winters.

There wasn’t much, just a brief newspaper article from 1897 about a 5-year-old girl who went missing from her home, presumed drowned in the nearby river after a storm caused flooding. Her body was never found according to official records.

But according to Martha’s journal, Margaret’s body had been found buried beneath a willow tree on my great-grandparents property. I needed to know more. I needed to understand what had happened to Margaret Winters and how Elizabeth had known where to find her. The next morning, I drove to the county historical society, housed in an imposing limestone building that had once been the town’s first bank.

Miss Abernathy, the elderly archivist, peered at me over her spectacles with interest when I explained my research. The Winter’s case? Now, there’s a name I haven’t heard in some time. And you say you’re related to the Caldwells? How fascinating. She led me to the archive room where microfilm reels of local newspapers were kept in metal cabinets.

Start with these,” she suggested, pulling out several labeled boxes. “1897 through 1903 should cover what you’re looking for.” Hours of scrolling through faded print revealed more details about the Winter’s case. The original disappearance had been front page news in the small town.

Child missing, feared drowned. Screamed the headline from June 19th, 1897. The article detailed how 5-year-old Margaret Winters had vanished from her home during a violent thunderstorm. The accompanying photograph showed a solemn little girl with dark ringlets and a white dress, remarkably similar in appearance to Elizabeth Caldwell.

Margaret Winters had disappeared on June 17th, 1897, exactly 5 years before Elizabeth’s birthday photograph was taken. The coincidence sent another chill through me. Search for missing winters. Child continues. read the headline a week later, describing how volunteers had dragged the river and searched the surrounding woods.

Margaret’s father, Harold Winters, was quoted pleading for information about his daughter’s whereabouts. The articles grew smaller and less frequent as weeks passed with no sign of the child. By August, Margaret Winters had become just another tragic footnote in local history, presumed drowned, though her body had never been recovered until August 1902 when Elizabeth Caldwell led adults to her burial site.

Further digging uncovered a follow-up article from August 1902 confirming Martha’s journal entries. Remains of long- missing child discovered, the headline announced. The article was frustratingly vague about details, but mentioned that the discovery was made after the young daughter of the household led adults to the location, claiming supernatural guidance.

The child’s remains were identified through personal effects and a distinctive silver bracelet gift from her godmother. The article went on to state that authorities were investigating the circumstances of Margaret’s death and burial with no suspects named at that time. I sat back rubbing my tired eyes. Miss Abernay appeared with a cup of tea and a sympathetic smile.

“Finding what you need?” she asked, glancing at the microfilm reader. “Yes, but I still have questions. Do you know anything more about what happened after they found Margaret Winter’s remains? The newspaper doesn’t mention any resolution to the case.” Miss Abernathy’s eyes twinkled. “You know, we have something that might interest you. Follow me.

” She led me to a climate controlled room at the back of the building. This is where we keep our more valuable collections. The Winter’s Caldwell case has its own file. She unlocked a cabinet and withdrew a slim folder. These are documents donated by the sheriff’s office when they digitized their archives in the 1990s. Not everything made it into the newspapers.

The folder contained handwritten police reports, witness statements, and a coroner’s assessment of Margaret Winter’s remains. The clinical language did little to disguise the horror. a skull fracture consistent with blunt force trauma, not drowning as had been presumed. They determined it was homicide, I asked, looking up at Miss Abernathy.

Eventually, yes, though the case took quite a turn. Keep reading. I turned to the next document, a statement from Sheriff Collins, dated September 1902. Having interviewed all members of the Caldwell household and their neighbors, I can find no explanation for how the child Elizabeth Caldwell knew of the burial location.

The girl maintains that the deceased’s spirit led her there. While I cannot accept such supernatural claims as evidence, I also cannot provide a rational explanation for her knowledge. The investigation into Margaret Winter’s death continues. But most revealing was a newspaper clipping I hadn’t found in the microfilm archives, dated December 18th, 1902. Local photographer takes own life, Harold Winters, 42, was found dead in his photography studio yesterday evening. the victim of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Mr.

Winters left a note confessing to the accidental death of his daughter Margaret in 1897 and the subsequent concealment of her body on the Caldwell property where he had been employed to photograph the gardens that same year. Authorities had reopened the investigation into Margaret’s death after her remains were discovered in August. Mr.

Winters is survived by no immediate family. Good heavens, I breathed, staring at the article. her own father. Miss Abernathy nodded solemnly. A terrible business. According to local stories, Winters was consumed by guilt after his daughter’s death. He continued working as a photographer, but became increasingly unstable.

When the girl’s remains were discovered, and the investigation pointed to him, he chose to end his life rather than face justice. But why would he bury her on the Caldwell property? I asked. Ah, well, that’s where the story gets more complicated.

Harold Winters and Thomas Caldwell had business dealings that went sour. Some said Winters buried his daughter there as an act of revenge, a curse on the property, if you will. Of course, that’s just local gossip. I thanked Miss Abernathy for her assistance and returned to my grandmother’s house, my mind whirling with this new information.

The photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon now seemed even more eerie. Had Harold Winters been the photographer that day? Had he taken a picture of another little girl standing exactly where his daughter was buried? I sat for a long time with these documents spread before me, trying to process what they revealed.

A tragic accident, a father’s terrible choice, a coverup that might never have been discovered if not for a child’s inexplicable connection to a spirit. And a photograph, a simple birthday portrait that captured what no one could see. the ghostly hand of Margaret Winters.

Reaching out from beyond the grave to connect with Elizabeth Caldwell, I returned to my grandmother’s house to the box of photographs. I examined each one carefully, looking for any other images of Elizabeth or perhaps even of Margaret Winters before her disappearance. In a smaller envelope at the bottom of the box, I found what I was looking for. Another photograph of Elizabeth.

This one dated October 1902, months after Margaret’s remains were discovered. Elizabeth stood in the same garden, but this time she wasn’t alone. A man stood beside her, his hand resting possessively on her shoulder. He was tall, well-dressed, with a neat mustache and cold eyes that seemed to stare directly at the camera with unusual intensity.

The inscription on the back read, “Elizabeth with Mr. Harold Winters, photographer. October 1902. Harold Winters, Margaret’s father. Why would he return to photograph Elizabeth after his daughter’s remains had been found on the property? Unless I pulled out Martha’s journal again, searching for mentions of Harold Winters after the discovery. There were several. September 15th, 1902. Mr.

Winters called today ostensibly to offer thanks for bringing closure to his daughter’s case. He seemed particularly interested in Elizabeth, asking many questions about her connection to Margaret. His intensity disturbed me. Thomas thinks I’m being unfair to a grieving father. But there was something in his eyes I cannot explain. A hunger almost.

As though he believed Elizabeth might somehow bring him closer to Margaret. I made certain they were never left alone. September 30th, 1902. Mister Winters has offered to take a new portrait of Elizabeth free of charge. As a token of gratitude, Thomas accepted before consulting me. I do not want that man near our daughter.

But Thomas insists I am being irrational. The poor man lost his child. He said, “If photographing Elizabeth brings him some comfort, what harm can it do? I cannot articulate my unease, even to myself, but every instinct tells me to keep Elizabeth away from Harold Winters.” October 5th, 1902. The photography session today was uncomfortable. Mr.

Winters insisted on being alone with Elizabeth for the individual portraits. When I objected, he became quite cold, reminding Thomas of their banking business connections. Thomas pulled me aside and insisted we not offend him. I relented, but stayed just outside the door. I could hear Winter speaking to Elizabeth in low tones, though I couldn’t make out the words.

When they emerged, Elizabeth seemed subdued, almost dazed. When I asked what they had discussed, she said only he wanted to know what Margaret tells me. Later, as Winters was packing his equipment, I noticed him lingering by the willow tree, his expression unreadable. October 20th, 1902. Elizabeth has begun having nightmares again. She woke screaming about the bad man last night.

When I asked who she meant, she would only say, “Margaret showed me what he did.” I’m certain she’s referring to Winters. Thomas says, “I’m leaping to conclusions that the discovery of Margaret’s remains has simply reawakened Elizabeth’s imagination, but there is a certainty in Elizabeth’s voice that chills me.

I’ve instructed the servants not to admit Winters if he calls again, regardless of Thomas’s business relationships.” My heart was pounding now. Was it possible? Could Harold Winters have been responsible for his own daughter’s death? It seemed unthinkable. But then, why had Margaret’s spirit reached out to Elizabeth? Why had she guided the child to her hidden grave? The final pieces came together when I found a small newspaper clipping pressed between the pages of Martha’s journal. Dated December 19th, 1902.

Winter’s confession reveals details of daughter’s death. The suicide note left by Harold Winters has provided authorities with a full account of the circumstances surrounding his daughter Margaret’s death in 1897. According to Sheriff Collins, Winters admitted to striking the child during a fit of anger, resulting in her fatal head injury.

Fearing the consequences, Winters concealed the body on the Caldwell estate where he was conducting photography work. The confession brings closure to one of our town’s most tragic mysteries. Though questions remain about how the young Caldwell girl led authorities to the burial site, Martha’s final entry about the matter, dated December 19th, 1902, was brief but revealing. Harold Winters is dead by his own hand.

His confession confirms what Elizabeth has been saying for weeks, that Margaret showed her what really happened. According to the sheriff, Winters admitted to striking Margaret during a fit of rage over a broken camera plate. The child fell against his desk, suffering the fatal injury. In panic, he buried her body while working on our property, never imagining that 5 years later, another little girl would somehow communicate with his daughter’s spirit.

Elizabeth says Margaret can rest now. I pray that is true. Thomas has suggested we might sell the house in the spring, make a fresh start somewhere without such painful associations. I am not opposed to the idea. Some shadows are too deep to dispel.

I sat for a long time with these documents spread before me, trying to process what they revealed. A tragic accident, a father’s terrible choice, a coverup that might never have been discovered if not for a child’s inexplicable connection to a spirit. And a photograph, a simple birthday portrait that captured what no one could see, the ghostly hand of Margaret Winters.

Reaching out from beyond the grave to connect with Elizabeth Caldwell, I carefully packed away Martha’s journal and the photographs, knowing I now possessed an extraordinary piece of my family history. But one question still nagged at me. Why had Margaret chosen Elizabeth? What connection had drawn the spirit of one child to another across the boundary between life and death? The answer came from an unexpected source.

While helping clear out the last of my grandmother’s belongings, I found a small box containing a locket. Inside was a tiny photograph I didn’t recognize. A solemn-faced woman in clothing from the 1890s. My grandmother’s caregiver, Mrs. Patterson happened to glance at it as she passed. “Oh,” she said casually. “That’s Lillian Winters. Your great great grandmother, isn’t it?” I stared at her in shock.

“Winters? Are you sure?” “Of course, dear. Your grandmother showed me that locket many times.” Lillian was her grandmother. Martha’s mother. Lovely woman by all accounts, though she died quite young. Consumption, I believe. I could barely form the words. So, Martha Caldwell was born Martha Winters. Yes. Changed her name when she married Thomas Caldwell. Of course, as was the custom.

Your grandmother said there was some scandal in the family history. Something about a cousin who did something terrible. She never liked to discuss it. A cousin. Harold Winters had been Martha’s cousin, which meant Elizabeth and Margaret had been second cousins. They shared blood.

That night, I took out the birthday photograph one last time, studying the smiling face of Elizabeth Caldwell and the empty space beside her where Margaret Winters stood invisible except for the impression of her hand. Second cousins reaching across the divide between life and death. One with a balloon celebrating her birthday. The other a ghost seeking justice and peace. As I studied the photograph in the dim light of my desk lamp, I noticed something I hadn’t seen before.

The balloon in Elizabeth’s hand wasn’t the simple round shape I’d initially thought. It had a distinct form, that of a willow tree. I turned the photograph over once more, reading the faded inscription, Elizabeth Caldwell, 6th birthday, June 17th, 1902. And beneath it, in different handwriting, nearly invisible with age, with Margaret finally at peace, I carefully placed the photograph in an acid-free sleeve for preservation. This was more than just a curious family heirloom. It was evidence of something extraordinary. A moment

when the boundary between our world and whatever lies beyond it had briefly thinned, allowing two children to connect across the divide. But my investigation didn’t end there. Something about the Winter’s case still bothered me. Harold’s confession had mentioned an accidental death, striking his daughter in anger.

But would that alone have driven him to such elaborate measures to hide her body? and why bury her on the Caldwell property specifically. I decided to dig deeper into Harold Winter’s history. The county records office yielded marriage certificates, property deeds, and business licenses. Harold had been a respected photographer in the community.

His studio on Main Street serving the county’s prominent families for nearly 20 years before his death. His wife, Catherine, had indeed died in 1899, 2 years after Margaret’s disappearance. The death certificate listed heart failure as the cause, though notes from the attending physician suggested profound melancholia had contributed to her decline.

The patient exhibits extreme lethargy and disinterest in life since her daughter’s disappearance. Dr. Mitchell had written, “Despite all treatments, including electrical stimulation and therapeutic baths, Mrs. Winters continues to deteriorate. I believe her heart failure stems primarily from her broken spirit.

More interesting was what I discovered about Harold’s relationship with the Caldwells. Business records showed that Thomas Caldwell’s bank had provided the loan for Harold’s photography studio in 1889. Further documentation revealed that in 1896, just a year before Margaret’s death, Thomas had called in that loan unexpectedly, forcing Harold to refinance at considerably higher interest.

A letter from Thomas to the bank board dated March 1896 stated, “While I sympathize with Mr. Winter’s financial difficulties, his connection to the Winter’s family through his marriage to my wife’s cousin does not entitle him to special consideration. Business and family must remain separate spheres.

Had there been bad blood between the men? Could Harold’s burial of Margaret on Caldwell property have been not just convenience, but a twisted act of revenge? I needed to understand more about Thomas Caldwell. Back to the historical society I went, combing through newspaper archives for any mention of my great greatgrandfather. What I found painted a complex picture.

Thomas Caldwell had been a prominent banker, yes, but there were whispers of unethical practices. Several foreclosures on local businesses raised eyebrows, especially when those properties were quickly acquired by Caldwell’s associates at suspiciously low prices. A small article from 1895 noted that T.

Caldwell esque has acquired the former Wilson property at a fraction of its assessed value following the unfortunate bankruptcy of its owner. This marks the third such acquisition by Mr. Caldwell or his associates this year. One such foreclosure involved a millinary shop owned by Catherine Wyinners before her marriage. The shop had been sold to a business partner of Thomas Caldwell just weeks after Catherine was forced to close it.

The connection was becoming clearer. There had been a history between these families beyond the cousin relationship. a history of business dealings and possibly personal animosity. But the most revealing document was one I almost missed.

In a box of miscellaneous legal papers from the county courthouse, I found a petition filed by Harold Winters in May 1897, just weeks before Margaret’s disappearance. The petition alleged that Thomas Caldwell had engaged in fraudulent banking practices and sought damages for deliberate manipulation of interest rates and calling of loans with malicious intent to cause financial harm.

The petition had been dismissed on June 16th, 1897, the day before Margaret disappeared. The timing was too perfect to be coincidental. Had Harold, distraught over this final defeat, taken his anger out on his daughter, and then, in a Macob act of vengeance, buried her on the property of the man he blamed for his financial ruin.

I returned to the photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon, June 17th, 1902. exactly 5 years after Margaret’s death. Was it mere coincidence that Margaret’s spirit had chosen that specific day to make contact? Or was there some significance to the date that I was still missing? My search led me back to my grandmother’s house to a cedar chest in the attic I hadn’t yet explored.

Inside, beneath quilts and christening gowns, I found a small wooden box. The brass plate on top bore a single name, Elizabeth. My hands trembled as I opened it. Inside were childhood treasures. A small porcelain doll with one arm missing. Hair ribbons in various colors. A child’s silver bracelet with tiny bells that tinkled faintly when moved.

And at the bottom, wrapped in tissue paper yellowed with age, a leatherbound diary much smaller than Martha’s journal. The first page confirmed my suspicion. This diary belongs to Elizabeth Anne Caldwell, age 6. Birthday gift from Aunt Emily, June 17th, 1902. Elizabeth’s diary. The entries began on her 6th birthday, June 17th, 1902. The handwriting was childish, unpracticed, but legible. Today is my birthday.

I am 6 years old. Mama gave me this book to write in. Papa gave me a balloon with a special picture. It looks like our willow tree. The photographer man came. He looked at me funny. I did not like him, but I liked the girl who came with him. No one else could see her. She held my hand when the photograph was taken. She told me her name is Margaret.

She says she is my friend now. I turned page after page reading Elizabeth’s innocent accounts of her interactions with Margaret’s spirit. Unlike her mother’s worried observations, Elizabeth wrote about Margaret with childlike acceptance, describing their games and talks without fear. June 25th, 1902. Margaret came again today. We played in the garden.

She can’t touch toys, but she can move them a little bit if she tries very hard. She says she is lonely. She used to live in a house with her mama and papa, but now she lives in the willow tree. She says the willow tree keeps her safe. July 2nd, 1902. Margaret showed me where she sleeps. It is under the willow tree by the pond. She says she has been there a long time.

She is lonely. I told her I would be her friend forever. We pinky promised even though I couldn’t really feel her pinky. She can make the air cold when she gets excited. Today she made my window very cold and I could see her name written in the frost. Mama didn’t see it. She says I have too much imagination. July 15th, 1902.

Margaret told me a secret today. She said the photographer man is her papa, but he did a bad thing. She won’t tell me what. She gets scary when she talks about him. Her eyes go all black and the room gets cold. She broke my doll’s arm by accident. She said sorry after. She doesn’t mean to be scary.

July 20th, 1902. I asked Margaret why no one else can see her. She said only special people can see the dead. She says it’s because we have the same blood. I don’t understand what she means. I asked Mama if we know Margaret’s family, but she got a funny look and said not to talk about it anymore. August 1st, 1902. Margaret is teaching me a game.

We go to the willow tree at night in my dreams. She shows me pictures in the pond. I saw her when she was alive. She had a pretty dress like mine. Then I saw her fall down. There was blood. The photographer man was there. He was angry. It was scary. I woke up crying. Mama sat with me, but I didn’t tell her about the dream. Margaret says it’s our secret.

August 10th, 1902. Margaret was angry today. She broke my music box. Mama thinks I did it, but it was Margaret. She’s angry because I played with Sarah yesterday and didn’t talk to Margaret all day. I told her I’m sorry. She said I have to prove I’m her friend.

She wants me to show everyone where she’s buried. She says no one will believe me, but I have to try. August 18th, 1902. I am sick. Mama stays with me all the time. Margaret wants me to go with her to the willow tree. She says I have to show everyone where she is sleeping. She says her papa put her there after he hurt her.

She says he has to tell the truth or she’ll never be able to go to heaven. I’m scared, but I promise to help her. The entry from August 20th confirmed what Martha had written. I went with Margaret today. Mama was sleeping in the chair. Margaret held my hand and we walked to the willow tree. She showed me exactly where to dig.

I tried to dig with my hands, but I got so tired. Then everything went dark. I woke up and Papa was carrying me back to the house. I told them Margaret is under the tree. Papa didn’t believe me, but Mama looked scared. They sent Henry to look. He came back all white and shaking. Papa went out with a shovel. They found Margaret’s bones. I could hear Mama crying.

Margaret stood by my bed and smiled. She said, “Thank you.” The entries continued through the discovery of Margaret’s remains, the investigation, and Harold Winter’s return to photograph Elizabeth. Her perspective on these events was both innocent and chilling. September 5th, 1902. They buried Margaret’s bones in the churchyard today. Everyone wore black. The photographer man cried a lot.

Margaret stood beside me during the service. She said it wasn’t really her in the box, just her old bones. She said she’ll stay with me until her papa tells the truth about what happened. September 20th, 1902. Margaret shows me things at night. She takes me back to the day she died. I see her papa’s photography studio.

She broke an expensive camera plate. He got very angry. He hit her and she fell. There was blood. He was scared after. He wrapped her in a blanket and brought her to our garden at night when everyone was sleeping. He buried her by the pond under the willow tree. Margaret says he has to tell everyone the truth or she can’t rest. October 5th, 1902.

The photographer man came today. He took my picture again. He asked me about Margaret. I told him she is my friend. He got very quiet. Then he asked if Margaret tells me things about him. I said, “Yes, she shows me in dreams.” He looked scared. Margaret was in the room with us. She was so angry. The chair moved by itself.

The photographer man saw it move. He turned all white after he left. Margaret told me he is a bad man. She showed me what he did to her. October 30th, 1902. Margaret is angry all the time now. She says her papa won’t tell the truth. She breaks things in the house. Mama and papa think it’s me, but it’s Margaret.

Last night, she stood over papa’s bed and screamed. He couldn’t hear her, but he woke up anyway. He said he felt cold. Margaret says she’s going to keep scaring people until her papa tells the truth. Elizabeth’s final entry about Margaret came on December 19th, 1902. Margaret came to say goodbye last night. She said her papa finally told the truth and now she can go to heaven. She was smiling. She didn’t look angry anymore.

She said she will always be my friend, but she won’t be in the willow tree now. She gave me a present before she left. A special picture in my mind of her when she was happy before the bad thing happened. I will never forget her. Mama says we might move to a new house.

I don’t want to leave because what if Margaret comes back to visit, but mama says Margaret is at peace now and won’t come back. I hope she’s happy in heaven. I closed the diary, overwhelmed by what I had discovered. Through the innocent writings of a child, a century old mystery had unfolded. A tale of financial rivalry, a moment of uncontrolled rage, a desperate cover up, and ultimately a spirit’s quest for justice. But there was one final piece to this puzzle I needed to find.

What had happened to Elizabeth after these events? Had her connection to the spirit world continued throughout her life? Martha’s journal had stopped mentioning supernatural occurrences after Margaret’s case was resolved. I searched through family records until I found Elizabeth’s path through life.

She had grown up, married a man named James Harrison in 1920, and had three children. My grandmother had been her youngest child. According to my grandmother’s personal papers, Elizabeth had lived a seemingly normal life after the events of 1902. She became a school teacher, was active in community affairs, and by all accounts was a loving mother and grandmother. She passed away in 1978 at the age of 82.

But tucked among my grandmother’s papers was a letter from Elizabeth to her daughter written in 1975, 3 years before her death. My dearest daughter, as I approach the end of my long life, there is something I feel compelled to share with you, something I have never spoken of to my children.

For fear you would think your mother touched in the head, you know the story of how I found poor Margaret Winter’s remains when I was a child. The family has always treated it as a curious anecdote, a strange coincidence, perhaps the overactive imagination of a child that happened to lead to a real discovery. The truth is far more extraordinary. Margaret was real.

Her spirit came to me on my sixth birthday and remained with me for those months in 1902. I saw her as clearly as I see you when you sit across from me at Sunday dinner. She spoke to me, held my hand, showed me visions of her life and death.

After her father confessed and took his own life, Margaret’s spirit moved on, but she left me with a gift or perhaps a burden. Since that time, I have occasionally been visited by others who have passed on with unfinished business. Never as strongly as Margaret, never for as long, but they come nonetheless. The young soldier in 1919 who needed me to return his watch to his sweetheart.

The little boy in 1933 who showed me where his mother could find the family savings his father had hidden before the bank collapsed. the young woman in 1954 whose murderer was never caught until she led me to evidence that had been overlooked. I have helped when I could, always quietly, always from the shadows.

Your father knew of this ability, but protected my secret faithfully until his death. I have told no one else until now. I share this with you not to distress you, but because I believe this sensitivity may be passed down through our family line. If you or your children ever experience something similar, know that it is not madness. It is a gift, though often a difficult one.

The photograph of me on my sixth birthday with the balloon, the one in your grandmother Martha’s collection, shows me with Margaret, though she is visible only by the impression of her hand holding mine. Keep it. Remember this story, and watch for signs in your own children and grandchildren. With all my love, mother, I sat back, stunned.

My grandmother had never mentioned this letter to me. Had she dismissed it as the fanciful thinking of an elderly woman? Or had she known it contained truth? And then I remembered something, a childhood incident I had nearly forgotten.

When I was 7 years old, I had led my grandmother directly to a lost wedding ring in the garden, insisting that the old lady with the blue dress had shown me where it was. My grandmother had given me a strange look, but never questioned how I knew. There had been other incidents over the years. Vivid dreams of people I’d never met telling me things I couldn’t possibly know.

A strong aversion to certain places that later turned out to have tragic histories. An uncanny ability to sense when something was wrong before being told. I looked again at the photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon and the invisible hand of Margaret Winters holding hers. The connection between these two children, second cousins, separated by death but united by blood and something beyond ordinary understanding, had apparently established a legacy that continued through generations.

Had Elizabeth passed this sensitivity to my grandmother? Had my grandmother passed it to me? Would I one day pass it to my own children? I carefully gathered all the documents, the photographs, Martha’s journal, Elizabeth’s diary, the newspaper clippings, and the letter.

Together, they told an extraordinary story of tragedy, vengeance, supernatural connection, and ultimately justice, and peace. As I placed everything back in the cedar chest, I felt a sudden chill in the room. For just a moment, I thought I caught a glimpse of two small figures standing by the window. A girl in Edwwardian dress holding a balloon shaped like a willow tree, and beside her, another child in slightly older clothing. Their hands linked between them.

Then they were gone and the room was empty again. But I was left with the unshakable feeling that my discovery of this family mystery had not been accidental. Perhaps Elizabeth had been right. Perhaps some connections truly do transcend death. I closed the cedar chest, but I kept the photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon.

I placed it in a frame on my desk, a reminder of an extraordinary moment captured on film. A moment when the veil between worlds had thinned enough for a camera to record what no living eye could see. The hand of a spirit child reaching across the boundary of death to find justice, closure, and perhaps most importantly, a friend who could see her when no one else could.

And sometimes late at night when the house is quiet, I look at that photograph and whisper, “Hello, Margaret. Hello, Elizabeth. I see you both.” Sometimes, I swear the balloon in the photograph moves ever so slightly, as though stirred by an otherworldly breeze.

And sometimes, just sometimes, I feel the gentle pressure of a small hand slipping into mine. The story of the girl with the birthday balloon is more than just a curious family tale. It’s evidence of connections that persist beyond death, of justice that can find its way through the most impenetrable barriers, and of the extraordinary sensitivity of children to realms that adults have forgotten how to see.

Elizabeth Caldwell grew up, lived a full life, and eventually passed on, perhaps reuniting with her childhood friend Margaret on the other side. But the photograph remains a testament to that brief miraculous moment when the living and the dead stood hand in hand, immortalized by the click of a camera shutter in a garden on a summer day in 1902. And I can’t help but wonder who else might be standing beside us in our photographs, invisible to the eye, but present nonetheless.

What other hands might be holding ours that we cannot see? Next time you look through old family photographs, pay close attention to the empty spaces, to the peculiar shadows, to the inexplicable blurs. You never know what or who might be captured there, reaching out across time and beyond death with a story that needs to be told.

After all, every photograph captures a moment in time. But some very rare ones capture something more. moments when the boundary between worlds grows thin enough for something extraordinary to slip through. Like the hand of a ghost child, holding tight to a living one, waiting for justice, waiting for peace, waiting to be seen, the girl with the birthday balloon saw what no one else could.

And now, through this photograph preserved for over a century, perhaps we can see it, too, if we look closely enough. if we believe. As I continued researching the Caldwell and Winters families, I discovered deeper connections than I had initially realized. Harold Winters and Martha Winters Caldwell hadn’t just been cousins.

Their fathers had been business partners in a photography studio in the 1870s before a bitter dispute led to the dissolution of their partnership. I found references to this partnership in an old business directory from 1872. Winters and Winters Photographic Studio specializing in portraiture and landscape views. According to a newspaper article from 1875, the partnership ended when the brothers Edward and William Winters disagreed over the adoption of new photographic techniques. Edward Herald’s father wanted to embrace the newer, more

expensive dryplate process, while William, Martha’s father, preferred to continue with the established wet plate method. The dissolution of the Winters Photography Partnership has caused much comment in local business circles. The article stated, “Mr. Edward Winters will continue operations under the name E.

Winters Fine Photography, while Mr. William Winters has announced his intention to pursue other business ventures. William Winters had indeed pursued other ventures, eventually establishing a successful dry goods store that provided him the means to send his daughter Martha to finishing school in Boston.

Edward Winters had struggled with his solo photography business, especially after expensive investments in new equipment failed to yield the expected returns. His son Harold had apprenticed with him, inheriting both his photographic skills and his financial problems when Edward died in 1888.

The rivalry between the families had continued for decades, culminating in the banking conflicts between Thomas Caldwell and Harold Winters. What had begun as a family disagreement had evolved into a multi-generational feud with innocent children caught in the middle. Margaret’s death in 1897 had been the tragic result of this long-standing animosity.

Harold, financially ruined in blaming Thomas Caldwell, had lashed out in a moment of rage when his daughter accidentally damaged an expensive camera plate. According to his confession, he hadn’t meant to kill her. He’d pushed her and she had fallen, striking her head on the corner of a heavy oak desk.

Panicked and already mentally unstable, Harold had made the fateful decision to hide his daughter’s body rather than face the consequences. And in a twisted act of vengeance, he chose the Caldwell property as her burial site. During a commissioned photography session of the garden, his suicide note, partially quoted in police records, revealed his disturbed thinking. I placed her where the blame should truly rest.

The Caldwell’s greed destroyed my business, my marriage, and ultimately led to my child’s death. Let her rest on their land, a silent witness to their crimes. For 5 years, the secret had remained hidden until Elizabeth’s sixth birthday, the exact anniversary of Margaret’s death, when the spirit of the murdered child had reached out to her second cousin, the daughter of the family her father blamed for his downfall. The irony was heartbreaking.

Two innocent children related by blood had become the means through which a terrible family legacy of hatred and revenge had finally been resolved. But the resolution had come at a price. Elizabeth’s innocence had been forever altered by her contact with Margaret’s spirit.

Her ability to see beyond the veil had been awakened, setting her on a lifetime path of occasional communications with the dead. And now it seemed that sensitivity had continued through the generations, manifesting in subtle ways in her descendants, including me. Since discovering the photograph and the documents explaining its history, I found myself more attuned to the inexplicable, the odd cold spot in an otherwise warm room, the whispered voice just at the edge of hearing, the momentary glimpse of a figure that vanishes when directly observed.

Last week, I visited the site where the Caldwell House once stood. The property had changed hands many times over the decades, and the original house had been demolished in the 1960s. A modern home now occupied the land, its owners unaware of the property’s haunted history. The willow tree was long gone, but I found its location based on old property maps.

Standing on that spot, I felt an unmistakable sense of presence, not threatening, but watchful, curious. I had brought a copy of the balloon photograph with me. As I stood where the willow tree had once grown, I held it up and spoke softly. Hello, Margaret. I know what happened to you. I know your story now.

The breeze picked up suddenly, swirling around me in a way that seemed deliberate rather than random. A child’s laughter echoed faintly, though there were no children nearby. The temperature dropped noticeably, my breath fogging in the sudden chill despite the mild spring day. “Your story hasn’t been forgotten,” I continued. “Elizabeth made sure of that. And now I’ll do the same.

As I turned to leave, I noticed something unusual on the ground near my feet. A small weathered piece of rubber, faded with age, but still recognizably part of a balloon. In an area that had been landscaped and rellandscaped countless times over more than a century, the likelihood of finding such an object exactly where I was standing seemed impossibly remote. I picked it up, turning it over in my fingers.

It crumbled slightly at my touch, confirming its age. Thank you, I whispered, not entirely sure who I was thanking. Margaret’s spirit, Elizabeth’s legacy, or simply the mysterious workings of a universe that occasionally allows the past to reach forward and touch the present.

I’ve continued my research into the Winter’s case, tracking down distant relatives of both families, piecing together more details of the tragedy and its aftermath. Most of those I’ve contacted have been unaware of the full story, knowing only fragments passed down through family lore. One elderly woman, a great niece of Harold Winters, provided an unexpected new detail.

According to family stories, Catherine Winters, Margaret’s mother, had possessed the sight, an ability to occasionally perceive spirits and premonitions. It drove her husband mad. The woman told me over tea in her assisted living facility. Harold couldn’t stand that Catherine saw things he couldn’t explain. He was a man of science, of proof, of photographic evidence.

The idea that his wife could perceive things beyond natural explanation threatened everything he believed about the world. She leaned forward, her voice dropping to a conspiratorial whisper. My mother told me that before Margaret disappeared, she had started showing signs of the same ability.

She would speak of people no one else could see, know things she shouldn’t have been able to know. Harold was terrified by it, tried to suppress it. Some in the family believe that’s what really triggered his rage that day, not just a broken camera plate, but Margaret saying something that revealed her developing sensitivity, something that reminded him too much of his wife.

This added a new dimension to the tragedy. Had Margaret inherited her mother’s sensitivity? Had Harold’s rage when striking his daughter been fueled not just by the broken camera plate, but by some manifestation of Margaret’s inherited ability? And most intriguing of all, had Margaret through her ghostly connection with Elizabeth somehow transferred or awakened this same sensitivity in her second cousin? Had the blood relationship between them, combined with Margaret’s violent death and Elizabeth’s innocent receptivity, created a doorway through which this ability could pass

from one branch of the family to another. The photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon had captured more than just a moment in time. It had captured evidence of an extraordinary connection between the living and the dead, between one generation and another, between justice delayed and justice finally served.

I’ve had the photograph professionally restored now. Digital enhancement revealed details not visible before. The faint outline of a second child standing beside Elizabeth. The subtle distortion of air where Margaret’s form stood invisible to the naked eye, but somehow partially captured by the camera’s lens.

Most remarkable of all, enhancement revealed a reflection in the glass of the garden greenhouse behind Elizabeth. In it, barely perceptible, but undeniably present, is the image of Harold Winters watching the photography session from a distance. His expression a disturbing mixture of grief, rage, and fear. The photographer that day hadn’t been Harold.

He’d sent an assistant, claiming illness. But he had been there, watching from hiding as another man photographed Elizabeth on the very ground beneath which Harold had buried his daughter 5 years earlier. Had he sensed something that day? Had he somehow known that his terrible secret was about to be revealed through the innocent connection between two children related by blood but separated by death? I may never know the full truth of what Harold Winters felt or feared on that June day in 1902.

But the evidence suggests he recognized something extraordinary happening. something beyond his rational understanding of the world. The photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon has become something of a legend among paranormal researchers who’ve heard of my discovery.

I’ve been approached by television producers, book publishers, and documentary filmmakers, all eager to share this remarkable story with a wider audience. But I’ve declined these opportunities, at least for now. This story feels too personal, too intimate to share widely. It belongs first to the families involved, to the descendants of Elizabeth and Margaret, to those who carry not just the blood, but perhaps also the sensitivity that links them across generations. Eventually, I’ll find the right way to share this story more broadly.

But for now, I’m content to continue my research to piece together more details of the lives of these two children who briefly reached across the boundary between life and death to connect with each other. The more I learn about Elizabeth’s life after her encounter with Margaret’s spirit, the more I’m convinced that the experience shaped her in profound ways.

Her school records show she excelled in literature and history, often writing essays that her teachers described as remarkably insightful for one so young and possessed of unusual empathy for historical figures. As an adult, she became not just a school teacher, but specifically a teacher who specialized in helping troubled children, those whom others had given up on.

A colleague quoted in her retirement testimonial said, “Elizabeth Harrison has an uncanny ability to understand what children are experiencing, even when they cannot articulate it themselves. It’s as though she can see directly into their hearts. And sometimes late at night when the house is quiet, I look at the photograph of Elizabeth with her birthday balloon and the invisible hand holding hers and I whisper, “Hello, Margaret.

Hello, Elizabeth. I see you both. Sometimes I swear the balloon in the photograph moves ever so slightly, as though stirred by an otherworldly breeze. And sometimes, just sometimes, I feel the gentle pressure of a small hand slipping into mine.” The story of the girl with the birthday balloon is more than just a curious family tale.

It’s evidence of connections that persist beyond death, of justice that can find its way through the most impenetrable barriers, and of the extraordinary sensitivity of children to realms that adults have forgotten how to see. Elizabeth Caldwell grew up, lived a full life, and eventually passed on, perhaps reuniting with her childhood friend Margaret on the other side.

But the photograph remains a testament to that brief miraculous moment when the living and the dead stood hand in hand, immortalized by the click of a camera shutter in a garden on a summer day in 1902. And I can’t help but wonder who else might be standing beside us in our photographs, invisible to the eye, but present nonetheless. What other hands might be holding ours that we cannot see? Next time you look through old family photographs, pay close attention to the empty spaces, to the peculiar shadows, to the inexplicable blurs.

You never know what or who might be captured there. Reaching out across time and beyond death with a story that needs to be told. After all, every photograph captures a moment in time. But some very rare ones capture something more. moments when the boundary between worlds grows thin enough for something extraordinary to slip through. Like the hand of a ghost child, holding tight to a living one, waiting for justice, waiting for peace, waiting to be seen, the girl with the birthday balloon saw what no one else could. And now through this photograph preserved for over a

century, perhaps we can see it too if we look closely enough. If we believe. Last month, I received an unexpected email from a woman named Clare Wilson. She had come across a blog post where I’d mentioned my research into the Caldwell Winters case. I believe we may share a connection, her message began.

My great-grandmother was Catherine Winters’s sister. I grew up hearing stories about cousin Margaret who vanished, but never knew the full truth of what happened. My family has always had unusual experiences. I wonder if we might compare notes. We arranged to meet at a cafe halfway between our homes.

Clare was in her 60s, elegant and composed with striking gray eyes that seemed to look through rather than at me. “It’s in the blood,” she said without preamble, stirring her tea. “The sensitivity,” Catherine had it strongly. “My grandmother said it skips generations sometimes or manifests differently in each person. Some just have dreams or intuitions. Others, like Elizabeth, see spirits clearly.

” “And you?” I asked. Clare smiled faintly. I know when the phone will ring before it does. I’ve dreamed of accidents before they happen. Small things mostly. My daughter, though, she hesitated. When she was 5, she had an imaginary friend named Margaret who wore old-fashioned clothes.

We thought nothing of it until she described a photographer’s studio in perfect detail, though she’d never been in one. We spent hours sharing family stories, piecing together the threads that connected our branches of the family tree. Before we parted, Clare pressed something into my hand. A small silver bracelet with tiny bells. “This belonged to Margaret,” she said softly.

“It was returned to the family after her remains were identified. “It should be with you now, I think. You’re the one telling her story.” The bracelet matched the description in Elizabeth’s diary. The bells tinkled faintly as I held it, a sound from another century. That night, I placed the bracelet beside the photograph on my desk.

As I drifted toward sleep, I could have sworn I heard the faint sound of children’s laughter and the delicate tinkling of tiny silver bells. The story of the girl with the birthday balloon continues to unfold, reaching across time, across generations, across the boundary between life and death.

A story of tragedy and justice, of family secrets and enduring connections, a story captured in a single extraordinary photograph. A child holding a balloon and the invisible hand of a ghost. Two second cousins reaching across the ultimate divide. One living, one dead, but both very real, both remembered, both seen. I keep the photograph and the bracelet together now, a tangible link to Elizabeth and Margaret, to their brief miraculous connection, to the legacy that flows through my veins, a reminder that some bonds transcend death.

That justice may be delayed but is not always denied. That the past is never truly passed, but continues to reach forward into the present, shaping us in ways we may never fully understand. And sometimes in the quiet hours before dawn, I wake to the faint sound of silver bells and children’s whispers.

And I know that I am not alone, that I have never been alone, that the blood of both Elizabeth and Margaret flows in my veins, connecting me to their story, to their extraordinary moment captured in a photograph over a century ago. A girl with a birthday balloon. A hand that wasn’t supposed to be there. A legacy passed down through generations. Some stories never truly end.

Some connections never truly break. Some photographs capture more than just light and shadow. They capture moments when the veil between worlds grows thin enough for something miraculous to slip through. Like the hand of a ghost child holding tight to a living one, waiting to be seen, waiting to be remembered, waiting to be understood.

The girl with the birthday balloon and the ghostly hand holding hers forever linked in a single impossible moment.