Have you ever walked outside during a thunderstorm and heard your blind son screaming only to find him tied to a tree with duct tape while lightning crackled overhead? Because I have. It happened during one of the worst storms our town had seen in years. The wind howled like it was ripping the world apart and rain pounded the windows like fists of fury.

I was home trying to fix a leaky pipe in the basement when I realized I hadn’t heard my son Ryan’s voice in a while. That’s not like him. He usually talks or hums as he moves through the house, tapping with his cane, navigating with the quiet strength that always humbles me. I called his name. No answer. I ran upstairs. No, Ryan. His cane was gone from the hook by the door. Panic hit me like a freight train. I bolted outside into the storm.

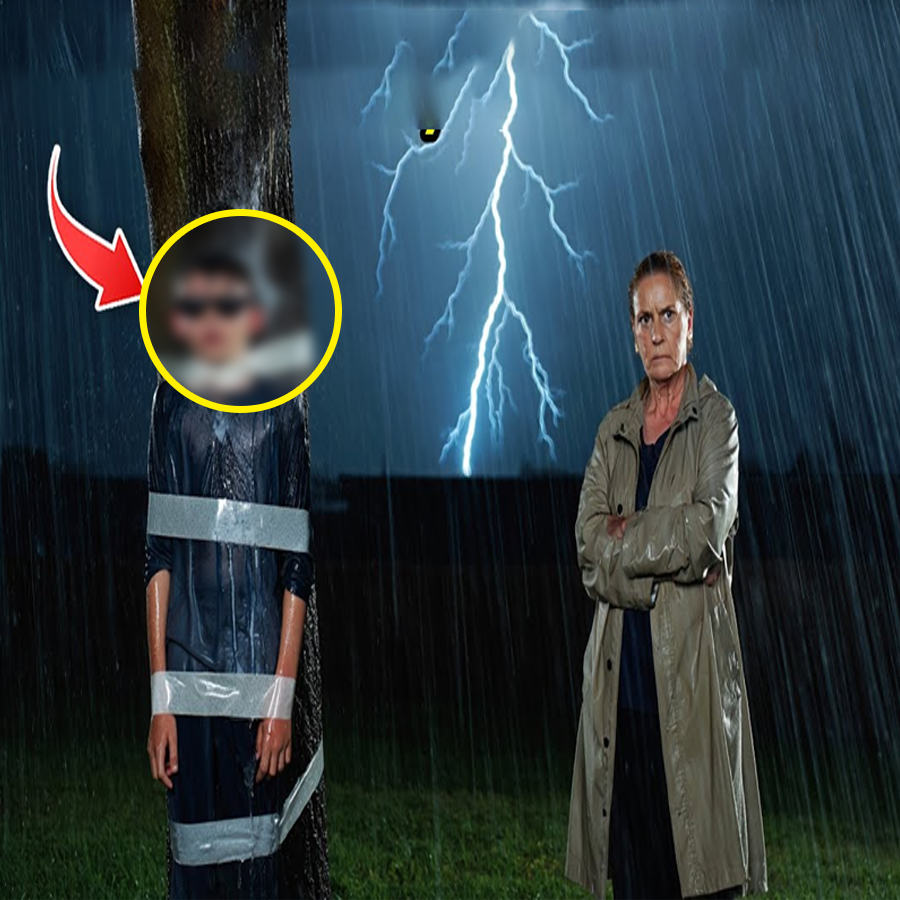

That’s when I heard it. A faint, terrified voice calling. Dad, help me. I followed it, heart pounding, feet slipping through the mud and pine needles. And there he was, my sweet blind boy, soaked, shaking, and duct taped to a tree like some kind of monster had done it for sport. Lightning struck another tree nearby just 3 minutes after I pulled him free.

And you want to know the worst part? It wasn’t some stranger who did this to him. It was our HOA president, Riley Hunter, a woman who said, “My son didn’t belong in this neighborhood. If you were me, what would you have done next? Tell me in the comments below.” Because this isn’t just a story about cruelty.

It’s a story about justice and what a father’s love can survive. My name is Todd Lawrence. I’m a father, a retired state investigator, and a man who’s seen some dark things in his life. But nothing prepared me for the moment I found my blind son duct taped to a tree in a lightning storm. Let me take you back. After I lost my wife to cancer 8 years ago, I raised Ryan alone.

He was just two then, barely old enough to say, “Mommy.” The diagnosis came when he was four, congenital retinal degeneration. The doctors were kind, but the words hit me like bricks. There was no cure, and there never would be. Ryan would never see the world the way most kids do.

But you know what? He saw it differently and beautifully. Ryan’s world was sound and texture and rhythm. He could tell you which direction the wind was blowing just by listening to the leaves. He knew which neighbor was mowing their lawn by the scent of grass clippings and the brand of gasoline. He memorized the shape of our street by the cracks in the sidewalk under his sneakers.

When people saw a disabled boy, I saw resilience. When others offered pity, I felt pride. Ryan didn’t complain. He asked questions. He wanted to help me cook, to walk the dog, to rake leaves, even though he couldn’t see the piles he made. We moved into Maple Glenn, a picturesque, quiet subdivision just outside Savannah, Georgia 3 years ago.

I wanted somewhere safe and peaceful where Ryan could grow up surrounded by kindness. It had clean streets, smiling neighbors, and a playground with soft mulch. It also had a homeowners association, but I figured, how bad could that be? We bought a small singlestory ranch house with wide hallways and a fenced backyard. I installed tactile floor strips to help Ryan navigate. Every inch of that house became part of his internal map.

I worked odd jobs online to stay home full-time. My days were filled with bedtime stories, tactile puzzles, braille homework, and making sure Ryan felt safe, strong, and loved. and he was every evening we had a routine after dinner Ryan and I would go for a walk around the block. He’d hold my arm and ask me questions about the color of the sky or what the clouds looked like.

He couldn’t see them, but he imagined them through my words. One time when he was eight, he said, “Dad, I think sunsets must sound like soft music.” I nearly cried right there on the sidewalk. Everyone who met Ryan loved him except one, Riley Hunter. She was new to the HOA board back then, just another neighbor with a clipboard and a little too much authority.

At first, she was polite. But soon, I noticed the glances she gave Ryan when he walked with his cane. One afternoon, she approached me and said, “He shouldn’t be walking alone. It’s dangerous. What if someone backs out of a driveway and doesn’t see him?” I smiled politely. He never walks alone. I’m always with him.

” She nodded, but her eyes narrowed. And from that moment on, things changed. We started getting letters. Petty violations. Our garbage bins were visible from the street for 12 minutes after pickup. Ryan’s windchimes created noise pollution. A handrail I installed on the porch for him was non-compliant.

Then came the demand to remove the small braille sign I’d mounted next to our mailbox. not uniform in style. Each time I complied or appealed. I didn’t want trouble. I wanted peace. But I underestimated Riley. What I saw as minor nuisances, she saw as warnings. And while I focused on creating a life of dignity and independence for my son, she focused on removing anything that didn’t fit her picture perfect version of the neighborhood. I tried to tell myself she was just uptight. I was wrong.

I didn’t realize that the woman with the clipboard wasn’t just a control freak. She was dangerous. And she had decided my son was a problem she intended to erase. Riley Hunter had that kind of smile that didn’t quite reach her eyes. She always wore lipstick too red for the occasion and heels that clacked like warning shots on the sidewalk. At first glance, she looked like a woman who had it all together.

Blazer pressed, SUV spotless, yard trimmed with ruler precision. But behind the manicured flower beds and perfect posture was a woman who needed control like other people need air. She became president of the Maple Glenn HOA about a year after we moved in. The previous president, a sweet old gentleman named Harold Wexler, retired and moved to Florida. Harold had a soft spot for Ryan. He always waved at him, even knowing Ryan couldn’t see it.

He can feel kindness. Harold once told me he hears it in your voice. But when Riley took over, the warmth drained from the neighborhood like someone pulled the plug. Her first act as president banning porch swings that squeaked. Then it was solar lights, unapproved garden gnomes, bird feeders, and any paint that wasn’t on the approved pallet. She held monthly inspections, not meetings, inspections.

And she carried a clipboard like it was a sheriff’s badge. Still, I didn’t expect her to single out Ryan. It started small. She complained about the clacking sound of his white cane on the pavement. It’s jarring for other residents, she said.

Then she told me that allowing Ryan to rake leaves in our front yard was unsafe and visually unappealing. She didn’t like the way he moved tentative, careful with outstretched hands. She said it made the neighborhood look unstable. I couldn’t believe it. This woman was suggesting that my son’s disability made other people uncomfortable. One day, Ryan was walking with me and accidentally brushed against a shrub in her yard while rounding the corner.

She stormed out of her house like I’d sent a wrecking crew to her patunias. He needs to stay off other people’s property. She snapped. You should keep him contained. Contained? Like he was some wild animal. I said nothing at the time, not because I agreed, but because I was afraid of what I might say if I opened my mouth.

And the last thing Ryan needed was his dad getting into a shouting match with a woman who clearly didn’t care about reason. After that, the HOA violations ramped up rapid fire. We were cited for non-standard landscaping because Ryan arranged his toy dinosaurs in the mulch by the porch. We were told his tactile garden markers were a tripping hazard.

She even called animal control on our dog Max, a senior golden retriever who rarely barks. The officer came, looked confused, patted Max on the head, and left. But Riley didn’t stop there. She went to the school board to question whether Ryan was mentally competent to be part of the public school’s inclusive education program. She posted a note on our mailbox. Maybe your child would be happier in a neighborhood more tailored to special needs.

That was the first time I saw real fear in Ryan’s face. Dad, he whispered, “Did I do something wrong?” “No, son. You did nothing wrong.” But Riley had declared war, and we were her target. Our neighbors were silent. A few gave sympathetic looks. One even left a pie on our doorstep without a note, but no one confronted her. Some were scared of her.

Others just didn’t want to get involved. She ruled through fear disguised as formality. It was more than harassment. It was eraser. She didn’t want to just push us out. She wanted to make us invisible. But Riley didn’t know who she was dealing with.

I might have traded in my badge and gun years ago, but I still remembered how to gather evidence, how to wait, how to strike when the time was right. And I was about to learn something that changed everything. She wasn’t just cruel, she was criminal. The day it happened started like any other with waffles, laughter, and a little routine.

It was a Friday, and Ryan had just finished his weekly Zoom lesson with Ms. Parker. He loved those sessions. She had a gift for painting vivid mental pictures for him, describing everything from the Great Wall of China to the feel of sunwarmed sand under bare feet. That day, they had studied thunderstorms, how they form, how they move, how they sound.

Funny, isn’t it, that the storm we studied would arrive just hours later and nearly take him from me. I spent the afternoon fixing a leaky pipe in the basement. Ryan was upstairs playing with Max on the sun porch. The forecast called for heavy rain, but down here in Georgia, that’s never too surprising. Still, I remember pausing, wiping my hands and hearing silence.

Too much silence, I called out, Ryan. No answer. I wiped off the wrench, rushed upstairs. No, Ryan. No, Max. His cane was gone from its hook by the door. That’s when my heart started to pound. I opened the front door and the wind hit me like a slap to the face. Leaves swirled. Trees bent under the pressure. And in the distance, thunder rumbled like cannon fire. I scanned the street. Nothing.

Then I heard it. A voice faint trembling carried by the wind like a whispered plea. Dad, help me. I sprinted. My shoes skidded across the wet concrete as I turned corners, leapt over puddles, and followed that voice. I passed the Thompson’s house, their porch light flickering. Donna opened her door, saw the look on my face, and pointed toward the woods behind the HOA community sign.

I bolted into the trees. The storm roared above. Branches snapped. My shirt clung to me like a second skin. Mud sucked at my boots. Then I saw it. a shape small, slumped, unmoving, taped to a pine tree. My son, his arms were pulled behind him. Duct tape wrapped around his chest and legs, binding him to the bark.

His cheeks were stre with rain and tears. His voice was, his cane lay broken on the ground. “Dad,” he sobbed. I didn’t know where I was. I tore at the tape like a madman. The bark bit into my fingers. Rain blurred my vision. And then it happened. crack. A blinding bolt of lightning tore through the sky and struck a tree just 20 ft away.

The sound was deafening like the earth had split in two. Flaming splinters showered the clearing. The heat washed over us. 3 minutes later and my son would have died. I wrapped him in my arms, shielding him, whispering, “I’ve got you. You’re safe now.” But inside something had snapped. This wasn’t bullying. This wasn’t petty.

This was attempted murder, and I had a damn good idea who was behind it. By the time we got home, Max had returned his fur soaked, limping slightly, but safe. Ryan, on the other hand, trembled non-stop. He didn’t speak. He didn’t eat. He sat on the couch in a blanket, rocking gently, head bowed. I made calls. First to 911, second to Sheriff Mark Davidson.

He arrived in 20 minutes, rain still dripping from the brim of his hat. We’d worked together for years in Atlanta. He’d seen me drag truth out of liars and put criminals behind bars. And now he stood in my living room listening as I told him what had happened. He knelt in front of Ryan, voice gentle. Buddy, can you tell me anything? Did you hear a voice? Ryan hesitated, then whispered. She said I was garbage. that I don’t belong here.

Mark looked up at me. He didn’t need to ask who. Riley. I gave him everything. The timeline, the location, the direction of the voice, the broken cane, the tape still with rain speckled fingerprints. He called in a crime scene unit that arrived within the hour. They photographed everything, bagged the tape, collected bark shavings. Then we made the next move.

While the officers worked the scene, I went to check Riley’s house. No answer, but her car sat in the driveway, soaked and steaming like it had just been parked. I looked around. Her front porch camera was angled just right. I walked back to my place and pulled up the last 24 hours of footage from my doorbell camera, praying for something, anything.

and I found it at 3:26 p.m. Just as the sky darkened, the footage showed Ryan stepping out, holding Max’s leash, humming quietly. At 3:28 p.m., Riley Hunter appeared, arms crossed, lips tight, walking behind him slowly. At 3:31 p.m., they disappeared behind the bushes that led toward the woods. She never returned on foot. She returned by car at 3:52 p.m.

Fem soaking wet, pulling into her garage. She’d left my son taped to a tree and gone home like it was just another item on her to-do list. Mark called a judge that night. By morning, they had a warrant. Officers knocked on her door at 7:00 a.m. She opened it with a robe on and an annoyed expression. Do you have any idea what time it they didn’t let her finish? She was cuffed before her coffee brewed.

charges aggravated child endangerment, assault, attempted manslaughter, hate crime enhancement, and as the news spread, something miraculous happened. The neighbors, who once said nothing, started speaking up. Bill Thompson admitted he once saw her screaming at Ryan near the HOA pool.

Donna said she’d overheard Riley muttering, “That blind brat,” under her breath, at the mailboxes. Another neighbor, Karen Lynn, confessed that Riley tried to pressure her into voting against allowing kids with disabilities to participate in HOA events. One by one, people came forward. Her perfect little kingdom crumbled like wet cardboard. The HOA board held an emergency meeting.

Riley was removed by unanimous vote. And Ryan, he slept soundly that night for the first time in days. But even as the community rallied behind us, I couldn’t shake the image of my son taped to that tree, vulnerable, alone, abandoned in a storm like he was disposable. And yet, even in that darkness, he survived.

Because my son, blind as he is, sees more truth, more courage, and more light than most people with perfect vision ever will. And Riley, she was about to face the storm of her own making. one that no umbrella of privilege or HOA title would ever shield her from. Some folks say revenge is a dish best served cold. Me, I believe in something better. Justice served warm, fresh, and with undeniable proof.

After Riley was arrested, most people figured the story was over. But that wasn’t enough for me. Not after what she’d done to my son. I didn’t just want her locked up. I wanted the truth exposed so thoroughly that no one would ever question why a boy like Ryan belonged in this community again for years. I kept my past quiet. I never led with it when we moved into Maple Glenn. I wanted Ryan to grow up normal, not as the kid with the ex- cop dad.

Most folks knew me as the quiet single father who fixed things himself, always kept the lawn trimmed, paid dues on time. But before all that, I was a special investigator for the state of Georgia. And not just any investigator. I was the guy they called in when things got complicated. Politicians, dirty nonprofits, cover-ups.

My job was to make sure the powerful couldn’t hide behind procedure. Now it was time to take those skills out of retirement. Mark and I went to work. We didn’t just want Riley convicted. We wanted her exposed for everything she’d done, not just what happened in the woods.

We pulled her back around and Mark got a hold of HOA records that most residents never saw. Turns out this wasn’t the first time she’d targeted someone. A Korean War veteran named Jim Alden was fined $1, $200 for having non-regulation fencing around his wheelchair ramp. Another family with a daughter in a walker had their driveway approval denied four times for design inconsistencies. Patterns. Clear, ugly patterns.

I knocked on doors. I recorded conversations with permission. I took statements. I compiled names, dates, copies of HOA letters, violation notices, complaint logs, everything. All signs pointed to a woman who weaponized neighborhood regulations to systematically push out anyone who didn’t fit her image of ideal. Mark brought in the district attorney.

Together, we presented a supplemental case file that included a dozen instances of discriminatory enforcement, testimonies from at least nine residents, and a psychological report stating that Ryan had been deeply traumatized by her actions. The DA’s office added civil rights violations to the list of charges. But that wasn’t all. Riley’s attorney pushed back hard. She’s a respected member of the community, he argued.

This was a misunderstanding, an attempt to discipline a child who was wandering unsupervised. Nice try. That’s when I decided to speak publicly. The local news had caught wind of the story, and a reporter asked if I’d be willing to comment. I said yes, but only if they came to my home and met Ryan first. The interview aired that night.

Ryan, sitting beside me, held Max’s paw in one hand and his cane in the other. he said softly. I didn’t do anything wrong. I was just walking with my dog. That single sentence pierced hearts across three counties. Then it was my turn. I looked into the camera and said, “My name is Todd Lawrence. I served the state for 24 years investigating abuse, fraud, and corruption.

I’ve seen cowards hide behind rules and bureaucrats. But never, not once, did I see someone use an HOA to try and erase a child. Phone lines at the station lit up. Social media exploded. People shared the clip with captions like, “Justice for Ryan and this is what courage looks like.” Neighbors who had stayed silent finally found their voice.

A week before the hearing, we held a neighborhood town hall in the community center. I didn’t plan on speaking, but someone asked me directly, “What would you have done if you’d arrived just a few minutes later?” I swallowed hard. I would have buried my son. The room went still and then applause, not polite clapping, not slow pity, real emotional applause from people who now understood. Riley’s day in court came sooner than expected.

She wore beige, no makeup, hair pulled back tight. She tried to look small, like the villain who suddenly realized she was a side character in someone else’s redemption story. The judge read the charges: child endangerment, assault, hate crime, civil rights violations, and abuse of authority as an HOA official. Her lawyer entered a plea deal.

She’d serve prison time, pay restitution, and be barred from ever holding a position on any HOA board again. And in a final twist of fate, the new HOA president was elected that same day. Her name, Donna Thompson, the same neighbor who pointed me toward the woods that night. She started the meeting with a motion to officially designate Ryan as an honorary ambassador for inclusive community values. It passed unanimously.

Back at home, Ryan sat in our backyard, his favorite spot, surrounded by the windchimes she once tried to ban. Dad,” he said, tilting his head to the breeze. “Do you hear that?” “Hear what, buddy?” He smiled. “Peace. It sounds like wind dancing with the trees.” I nodded. He was right. For the first time in a long while, the air didn’t feel heavy.

And in that moment, I knew something deep in my bones. This battle wasn’t just about Ryan. It was about every person who’s ever been told they didn’t belong. and every parent who refused to accept that. You never forget the sound of a courtroom when justice finally breathes.

It’s not loud, not like in the movies. No slamming gavels or dramatic gasps. It’s quiet, measured, final. That’s how it was the day Riley Hunter was sentenced. She stood alone, wearing a pale gray suit, hands folded tightly in front of her.

No clipboard now, no polished smile, just a nervous twitch in her jaw and eyes darting toward the rose behind her. But everyone in that room was looking at one thing, Ryan. He was seated to my left, dressed in his Sunday best. He held his cane in his lap and sat tall, proud. No one prompted him. No one told him to. He just knew he belonged there. The judge, a soft-spoken woman in her 60s, began by reading the charges one by one.

Her voice was steady, almost clinical, aggravated assault on a minor. Reckless endangerment, bias motivated intimidation, abuse of authority as a community official. Each word felt like a chisel carving truth into stone. Then came the sentencing, five years in state prison, mandatory mental health evaluation, $85 dollars in restitution donated to organizations supporting children with disabilities, permanent ban from HOA participation or public administrative roles. When the judge asked if the defendant had anything to say, Riley rose slowly. Her voice

trembled as she said, “I was trying to maintain order. I never meant harm. I just thought people like that.” She stopped herself. Her lawyer put a hand on her shoulder. She sat down. The room was silent. Then the judge looked to me. “Mr. Lawrence, would you like to make a final statement?” I stood. I didn’t bring notes. I didn’t need them.

Your honor, I began. I’ve spent my life investigating lies and exposing those who abuse power, but nothing nothing compared to the night I found my son duct taped to a tree during a lightning storm. I paused. I want everyone here to remember this. Ryan isn’t broken. He’s not less than. He’s more than many of us. More resilient, more kind, more courageous.

Riley didn’t just try to silence a child. She tried to erase a human soul. I looked down at my son and she failed. The judge nodded. Thank you, Mr. Ye. Lawrence. You may be seated. That night, the town paper printed the headline, “HOA president sentenced for hate crime against disabled child.” Right underneath was a picture of Ryan smiling, holding Max’s leash, standing beside a new community sign that read, “Maple Glenn, a neighborhood for all.

” The sign was the first change under Donna Thompson’s new leadership, but it wasn’t the last. In the weeks that followed, a wave of reform swept through Maple Glenn. The HOA’s bylaws were rewritten with accessibility and inclusivity as core values. Gone were the discriminatory clauses, vague aesthetic rules, and silent threats buried in fine print.

In their place, transparency, accountability, and compassion. Ryan was asked to join a newly formed advisory committee alongside Donna and Ms. Parker. They called it the Harmony Council. their mission to ensure no resident, especially those with disabilities, would ever be made to feel like outsiders again. At the council’s first meeting, Ryan shared an idea.

What if we added texture paths through the neighborhood like a map I can feel with my feet? The room lit up with nods and smiles. Donna approved the plan on the spot. Construction began the following month. Something else changed, too. The neighbors people who once averted their eyes or kept their heads down began opening up. Mr.

Henderson, a widowerower down the block, stopped by with stories of his own son who’d had learning disabilities. He brought Ryan homemade fudge every Friday. Kids from Ryan’s school started joining him on evening walks. They learned to describe things for him.

The shape of clouds, the sway of tree branches, the way light played on puddles. One boy even said, “Ryan helps me see better.” It was true in more ways than one. As for Riley, she tried appealing her sentence. The court denied her request. Word spread to nearby towns. Other HOAs reviewed their own rules. The story appeared in statewide newsletters about civil rights and disability advocacy.

I was asked to speak at two town halls and one virtual conference for HOA accountability, but none of that mattered as much to me as this Ryan no longer woke up crying in the night. He didn’t flinch when thunder rolled across the sky. And one warm spring morning, he asked if he could go sit by that same tree in the woods. I hesitated, then nodded.

We walked together. When we arrived, he reached out, touching the bark gently with his fingers. It’s not scary anymore,” he whispered. “It’s just a tree.” I felt a tear slip down my cheek. He looked up toward the canopy and said, “Do you think lightning remembers where it struck?” I smiled. “Maybe, but I think that tree remembers you, too.” The storm had passed.

The damage had been done, but healing. Real healing had begun. Not just for Ryan, for all of us, for every person in that neighborhood who’d once looked the other way. And now look directly at what matters truth, courage, and community. A year later, on the anniversary of that storm, we held a small gathering under the tree where it all happened. The pine still stood tall, scarred, but strong, just like Ryan.

Donna brought folding chairs. Miz Parker brought cupcakes. Sheriff Davidson brought his old acoustic guitar. Even the Thompsons, now unofficially dubbed the grandparents of the neighborhood, brought balloons that whispered in the breeze like soft laughter. Ryan stood in the center, Cain in one hand, Max in the other.

I don’t remember everything from that day, he told the group, just the wind and my dad’s voice. But I remember feeling scared. And then I remember feeling safe again. He smiled. Sometimes bad things happen so good things can grow. The crowd went quiet. Then one by one they clapped, not loud or showy, but real.

Later that evening, as the sun dipped below the treetops, I sat on our porch with Ryan curled beside me, his head resting against my shoulder. “Dad,” he said, “do you think people can change?” I looked out at our peaceful street, now lined with textured paths, adaptive signage, and front yards filled with warmth instead of rules.

I think people can change, I said, if they’re brave enough to see what needs changing. He nodded once, content, and I realized something I hadn’t said out loud yet. I’m proud of you, Ryan. Not just for surviving what happened, but for teaching the rest of us what it means to live. Because in the end, this wasn’t just a story about a cruel woman or a storm.