October 14th, 1942. 11:42 a.m. Occupied Poland. The temperature is 6° C. The sky is a piercing cloudless blue. A German supply train is screaming down the tracks toward the eastern front. It is a fortress on wheels. It carries 3 million Reich marks worth of high octane aviation fuel.

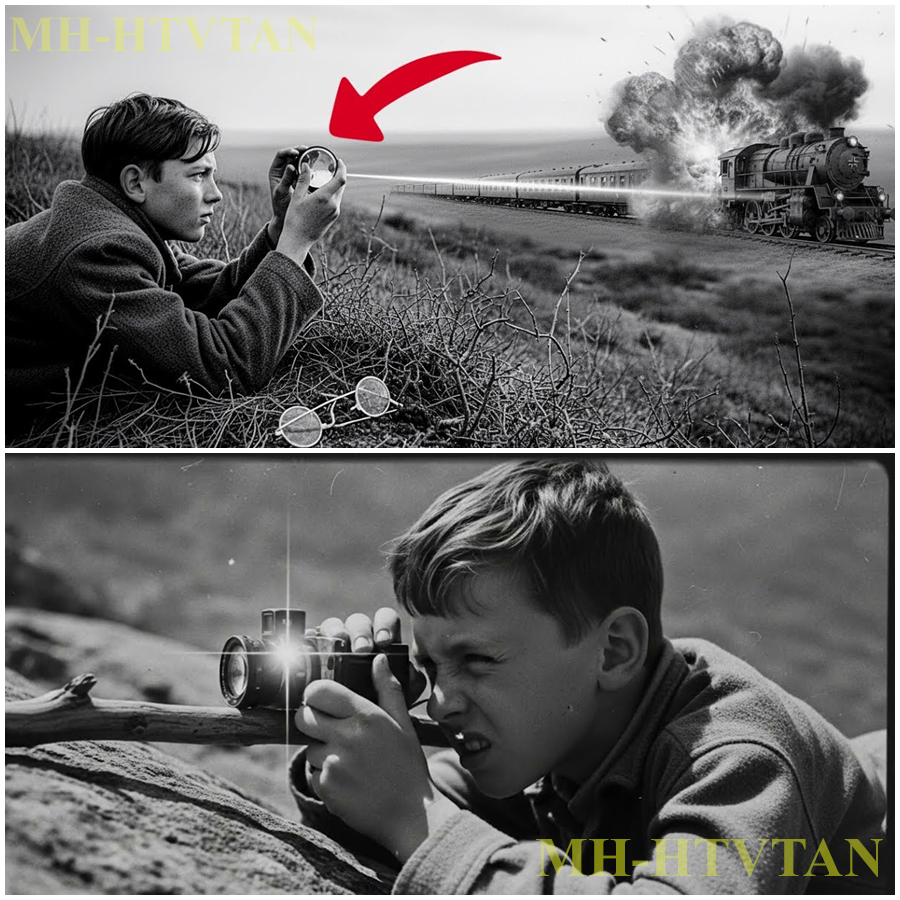

It is guarded by 12 soldiers with machine guns. It is protected by armored plating. It is unstoppable. 400 meters away, hidden in the treeine, a 12-year-old boy named Yseph is not holding a gun. He is not holding a grenade. He is holding a piece of broken glass. He is calm. His heart rate is steady.

He is not fighting a war with bullets. He is fighting with physics. He adjusts his hand by 2 mm. He waits for the train to hit the curve. He catches the sun. 3 seconds later, the impossible happens. The lead tanker car doesn’t just catch fire. It disintegrates. A fireball the size of a cathedral erupts into the autumn sky. The train derails.

Steel twists like wet paper. The guards are incinerated before they can even lift their rifles. The German high command will spend the next two years hunting for a team of elite British commandos. They will torture hundreds of suspects. They will analyze bomb fragments that don’t exist. They will tear the countryside apart looking for a phantom.

They never looked for a child and they never looked at the sun. This is the untold story of the youngest, deadliest, and most impossible sabotur of World War II. This is how one boy turned the light of day into a weapon of mass destruction. To understand how a child becomes a monster hunter, you first have to understand the monster.

By late 1942, Poland wasn’t a country anymore. It was a graveyard. The map said general government, but the people knew it as the cage. The Nazis had crushed the Polish army in 36 days back in 39. Now 3 years later, the occupation had settled into a terrifying mechanical routine. We need to talk about the silence.

In the cities like Warsaw, there was noise, gunfire, sirens, screams. But in the countryside, in the tiny village where Yseph lived, the horror was quiet. It was the silence of people who had learned that speaking meant dying. Ysef was small for his age, malnourished, ribs showing through his shirt. He lived in a wooden cottage that leaned against the wind right on the edge of the forest.

He lived with his grandmother, Awa. She was a woman carved out of granite and grief. Why just his grandmother? Because the Germans had taken the rest. August 1941. That was the day Ysef’s childhood ended. An SS truck had rolled into the village. They weren’t looking for resistance fighters. They were looking for labor. They took his father to a factory in Essen. They took his mother to a camp whose name no one dared to whisper.

Ysef had watched from the cellar through a crack in the floorboards as they dragged his parents out into the sunlight. That was the last time he saw them. And that was the moment a switch flipped inside his brain. Most children would have broken. Most would have cried. Ysef didn’t cry. He went numb.

This is a psychological phenomenon known as emotional blunting. It’s a survival mechanism. When the trauma is too big to process, the brain simply shuts down the emotional centers to protect the logic centers. Ysef became an observer, a data collector. He spent his days sitting on the roof of the cottage watching. He watched the patrols.

He watched the trucks, but mostly he watched the trains. The railway line ran through the valley about 500 m from his house. It was the aorta of the Nazi war effort. Every day 20, 30, sometimes 50 trains rumbled east. tanks for Stalenrad, winter coats for the Vermacht, artillery shells for the siege of Lennengrad. Yseph hated them. But he didn’t just hate them with anger.

He hated them with curiosity. He memorized their schedules. He noticed that the fuel trains, the ones with the yellow diamond symbols, always slowed down at the dead man’s curve, a sharp bend where the track rose at a steep grade. He knew he wanted to destroy them. But he was 12. He weighed 40 kg. He had no gun. He had no explosives.

He was mathematically speaking zero threat to the Third Reich until the day he broke his grandmother’s glasses. It was an accident. It was a hot day in July. His grandmother had dropped her reading glasses. The frame snapped and the left lens popped out. Yseph picked it up.

It was a thick convex lens, old glass, imperfect, but powerful. He sat on the porch, bored, twisting the lens in his fingers. The sun was beating down. A high pressure system over central Europe meant the sky was white hot. Idly, without thinking, Ysef focused a beam of light onto a dry pine needle on the railing. He watched the dot. It was bright, painfully bright smoke.

A tiny wisp of gray smoke curled up. Then a snap. A flame. Ysef stared at it. He stomped it out. He did it again. This time on a piece of newsprint. Flash. It ignited in 3 seconds. Now we need to understand the physics because this is what the Nazis failed to calculate. This isn’t magic. It’s thermodynamics.

The sun deposits about 1,000 watts of energy per square meter on the Earth’s surface. A normal reading lens might have a surface area of about 20 square cm. When you take all that energy, all those photons slamming into the glass, and you force them to converge into a focal point the size of a pin head, you are creating a localized thermal event. At that tiny focal point, the temperature isn’t just hot.

It can reach over 500° C in seconds. The flash point of dry wood is 300°. The flash point of gasoline vapor -43° C. Gasoline vapor is begging to explode. It just needs a spark. Ysef looked at the burning paper. Then he looked up at the valley. He looked at the tracks. Specifically, he looked at the dead man’s curve. He remembered the fuel trains.

He remembered the smell of them as they passed. That faint chemical scent of leaking fumes. German wartime production was rushing. The welds on the tanker cars were sloppy. The seals were cheap rubber. On a hot day, those tankers were surrounded by an invisible cloud of volatile vapor. Yseph didn’t have a weapon.

He realized with a jolt of adrenaline that almost made him vomit that he was holding a detonator. The sun was the weapon. The lens was just the trigger. But a 12-year-old boy doesn’t just wake up and become a sniper. He had to train. For the next 6 weeks, Ysef turned into a scientist of sabotage.

He went deep into the woods, far from the village. He practiced. He learned that the angle matters. The sun moves across the sky at 15° hour. You have to lead the target. He learned about focal length. You can’t just hold the glass anywhere. There is a precise distance, the sweet spot, where the beam is tightest. Too close, it’s just a warm circle. Too far, it diffuses.

It had to be exact. He learned about stability. His hands shook. A shaking hand spreads the heat, preventing ignition. He needed a rest, a bipod. He built one out of fallen branches. He created a game. He would float pieces of bark down the creek, pretending they were trains.

He would sit on the bank, track them with his lens, and try to burn a hole in them before they passed a certain rock. First week, failure. Second week, he could scorch the bark. Fourth week, he could set a moving leaf on fire from 10 m away. He was ready. But he wasn’t just fighting physics. He was fighting fear.

Because if he missed, if he was seen, if a flash of light caught a guard’s eye, it wasn’t just him who would die. The SS would burn his grandmother alive in her house. That was the German policy, collective responsibility. The weight of that decision crushed him, but the memory of his parents dragged him forward. October 1942, the dead man’s curve. Ysef chose a Tuesday.

Why? Because on Tuesdays, the heavy supply train from Warsaw came through at 11 a.m. He woke up before dawn. He felt sick. His hands were trembling so badly he couldn’t tie his boots. He ate a piece of stale bread, drank water, and looked at his grandmother. She was sleeping. He whispered a goodbye that she couldn’t hear just in case. He crept out of the house.

The frost was heavy on the grass. He moved like a shadow, staying low, using the drainage ditches, avoiding the road. He reached his spot. A cluster of gray rocks on a ridge overlooking the tracks. Elevation 15 meters above the track. Distance 60 m. Sun position directly behind him. Perfect. He set up his nest. He cleared the dry leaves so he wouldn’t accidentally start a fire near himself. He positioned his branch bipod.

He took out the lens wrapped in a dirty rag. He waited. 10:4 a.m. Nothing. 10:30 a.m. A passenger train useless. 10:55 a.m. He felt the e E vibration before he heard the sound. The ground hummed. Then came the whistle, a shriek of steam. The train appeared around the bend. A black iron beast spewing smoke.

Ysef counted the cars. One, two, flatbeds with trucks. Three, box car. Four target. A line of six tanker cars painted gray. The yellow diamond warning symbols were coated in dust but visible. The train hit the grade. The engine groaned. The speed dropped. Chug. Chug. Chug. It was moving at maybe 15 kmh. Ysef stopped breathing.

He placed the lens on his branch. He angled it. A bright blinding dot of light appeared on the side of the third tanker car. steady. He moved the dot, hunting for a weakness. He didn’t aim for the steel tank. Steel takes too long to heat. He aimed for the relief valve on top, the mechanism designed to let vapor out so the tank doesn’t explode from pressure. It was the weak point.

It was where the fumes were. He locked the beam onto the valve. 1 second. The dot danced slightly. 2 seconds. He bit his lip until it bled to steady his hands. 3 seconds. Nothing. The train was moving away. He was losing the angle. Panic surged in his chest. It didn’t work. It was a stupid idea. He was a stupid boy with a piece of trash. 4 seconds and then he saw it.

Not a fire, but a shimmer. Like a heat mirage dancing above the valve. The vapor was heating up. 5 seconds. Whom? It wasn’t a bang. It was a wump of air being sucked into a vacuum, followed instantly by a roar. The top of the tanker car didn’t just catch fire. It bloomed. A geyser of orange flame shot 20 ft into the air.

Ysef didn’t watch. The moment he saw the flash, instinct took over. He dropped the lens into his pocket and rolled backward into the ditch behind the ridge. Boom. The secondary explosion shook the ground beneath him. It was deafening. The tank had ruptured.

Thousands of lers of burning fuel were cascading over the tracks, pouring onto the wheels, melting the grease. The train screeched. A metal-on-metal scream of agony. Ysef crawled. He didn’t run. Running attracts the eye. He crawled on his belly through the freezing mud, dragging himself through the undergrowth like a snake. Behind him, hell had opened up. He could hear shouting now.

German voices, panic, screams, the pop pop pop of ammunition cooking off in the other cars. He made it to the treeine. He stood up and sprinted. He ran until his lungs burned, until his legs felt like lead. He burst into his grandmother’s cottage, pale, sweating, shaking violently. He went to the window and looked out. A pillar of black smoke, thick and oily, was rising into the sky.

It was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen. He had done it. But he had made a mistake, a terrible tactical mistake. He thought he was anonymous. He thought the Germans would blame a mechanical failure, but the Germans were not stupid. They were methodical, and they were about to send a man who specialized in impossible crimes. The explosion at Dead Man’s Curve did not go unnoticed.

In Berlin, it was a logistical statistic. A red line through a supply manifest. But in the local district headquarters, it was a crisis. 3 days after the attack, a black Mercedes staff car rolled into the village. It didn’t stop at the local garrison. It drove straight to the wreckage site. Outstepped a man who didn’t look like a soldier.

He looked like an accountant who had traded his ledger for a lugger. Ober Stormfurer Klaus Reinhardt. Reinhardt was not SS. He was Gestapo technical branch. He was a specialist in counter sabotage forensics. He didn’t scream at villagers. He didn’t burn houses. Not yet. He looked at twisted metal. He walked the tracks.

The wreckage had been cleared, but the scars remained. The burn marks on the gravel, the melted sleepers. Reinhardt knelt by the spot where the tanker had exploded. He ran a gloved finger over a piece of shrapnel. He was looking for chemical residue. Potassium chlorate, TNT, dynamite, the signature of the Polish underground.

He found nothing. He walked up the embankment. He looked at the trees. He looked for trip wires. He looked for battery cables. He looked for footprints. He found nothing. He stood there for a long time staring at the empty curve. His lieutenant asked him, “Partisans, sir.” Reinhardt shook his head. “Partisans are messy.

Partisans use old Soviet mines that leave nitrate burns. This This was clean.” He looked up at the ridge where Ysef had lain. He narrowed his eyes. “Too clean,” he whispered. “Whatever hit this train didn’t explode on the train. It ignited it.” Reinhardt wrote one word in his notebook. Anomaly. He ordered the patrols doubled. He ordered the trees cut back 50 m from the track.

He was tightening the noose around a ghost he couldn’t see. Ysef watched all of this from his roof. He saw the black car. He saw the trees being cut. He felt a cold knot of fear in his stomach. The Germans were adapting. They were removing his cover. If he went back to the ridge, he would be spotted instantly. Most people would have stopped.

The logical thing to do was burn the lens and go back to being a child. But Ysef wasn’t thinking about logic. He was thinking about the smoke. He was thinking about the fact that for the first time in 3 years, the Germans were afraid. He couldn’t stop. But he couldn’t stay the same. He had to evolve. The weeks turned into months. Winter came and went.

The snow made attacks impossible. No sun, no heat. Ysef used the time to study. He realized his first attack was lucky. He had been too close. 60 m was suicide. He needed range. He needed to become a sniper. He stole a physics textbook from the ruins of the village school library.

He couldn’t read all the German words, but he understood the diagrams. He learned about columnation. He realized that if he wanted to burn something from further away, he needed a steadier hand and a clearer day. He couldn’t just hold the lens. He needed a mount. He found an old hollowedout log near the creek. He carved a groove into it. He tested it by wedging the lens into the wood.

He could eliminate the micro tremors of his pulse. He could hold a beam steady on a target for 30 seconds without moving a muscle. Spring 1943 arrived. The sun returned, stronger than before. Ysef picked a new target, not a curve this time. A bridge. The river Naru bridge was a steel truss structure vital for trains heading north.

Trains had to cross it at a crawl to avoid vibrating the foundations. The problem was security. The bridge had guard towers at both ends, search lights, machine gun nests. But the Germans had a blind spot. They were watching the river banks for boats. They were watching the tracks for mines. They weren’t watching the limestone cliffs 300 m

away. 300 m. It was an insane distance. At that range, the focal point of his lens would be fragile. A gust of wind could diffuse it. A cloud could ruin it. But Yseph had done the math. The angle of the sun at $2 p.m. would hit the cliff face perfectly. May 12th, 1943. Ysef climbed the cliff. It took him 2 hours to inch his way up the rock face, carrying his lens in a padded sock.

He wedged himself into a crevice. He was invisible from below, a speck of dust on the landscape. Below him, the river churned. The bridge looked like a toy. At 2:14 p.m., the vibration started. It was a heavy transport. Flatbeds loaded with Tiger tanks, and in the middle, five fuel tankers to keep them running.

Ysef set his log mount. He inserted the lens. The sun was a hammer on the back of his neck. He found his target, the second tanker. At 300 m, the physics changed. The atmosphere itself became a barrier. Dust, pollen, moisture, everything scattered the light. Ysef had to be patient.

He had to wait for the air to settle. The train crawled onto the bridge. The guards in the towers were smoking, looking down at the water. Yseph focused the beam. It was faint, much fainter than before. It wasn’t a blinding dot. It was a soft, shimmering coin of light. He held it on the valve. 10 seconds. Nothing. 20 seconds.

The train was halfway across. 30 seconds. His eyes were watering from the glare. Burn, he whispered. Please. The shimmering coin of light stayed locked on the black metal. The heat was building molecule by molecule, fighting the wind, fighting the distance. 40 seconds. The tanker was almost at the end of the bridge. He had failed. The distance was too great.

And then the physics tipped the scale. The valve seal melted. A jet of pressurized gas hissed out. It hit the concentrated beam of photons. Ignition. It wasn’t a fire. This time it was a detonation. The tanker exploded while still inside the steel truss of the bridge. The force of the blast was contained by the girders, amplifying the shock wave.

The sound was like the earth cracking open. Ysef watched in awe as the steel truss buckled. The heat from the burning fuel melted the structural rivets with a groan that echoed across the valley. The center span of the bridge gave way. The burning train, the tanks, the fuel. It all plunged 50 m down into the river.

A massive plume of steam and smoke rose up, hiding the destruction. Ysef didn’t stay to watch. He scrambled back down the cliff, scraping his hands raw. He ran through the forest, his heart pounding a rhythm of pure victory. He had destroyed a bridge. He had dropped tanks into a river. He was a god. He returned to the village just as the sun was setting. He expected to feel triumphant.

He expected to feel like a hero. Instead, he walked into a nightmare. The village square was full of soldiers. Trucks were idling. Reinhardt was there. But Reinhardt wasn’t looking at twisted metal today. He was looking at a list. The explosion at the bridge had been too much. The Germans couldn’t find the sabotur, so they did what they always did. They took the cost out of the locals.

Ysef stood in the crowd, hidden behind the legs of adults. He watched as soldiers dragged 10 men out of their homes. the baker, the school teacher, the blacksmith, men Ysef had known his whole life, men who had given him apples when he was hungry. Reinhardt stood on the steps of the town hall. He adjusted his glasses.

He spoke calmly. “Sabotage has a price,” he said. “If the criminal will not step forward, the community will pay his debt.” They didn’t shoot them. They hanged them right there in front of everyone, in front of Yseph. The silence of the village was broken by the sound of weeping women. Ysef stood frozen. He couldn’t breathe. He couldn’t blink. He looked at the baker’s swinging body.

And then he looked at his own hands, the hands that had held the lens. These were not the hands of a hero. These were the hands of a murderer. He ran home. He vomited in the garden. He crawled into his bed and pulled the blanket over his head, shaking uncontrollably. He wanted to smash the lens. He wanted to throw it into the river. He wanted to scream at the Germans. It was me.

Take me. But he couldn’t because if he confessed, they wouldn’t just kill him. They would kill his grandmother. They would burn the village. He was trapped. For 3 weeks, Yseph didn’t leave the house. He sat in the dark. The guilt was a physical weight, pressing on his chest. He stopped eating. He saw the baker’s face every time he closed his eyes.

But outside, the trains kept coming. He heard them at night. The rumble, the whistle, the sound of the Nazi war machine feeding on his country. and he realized something terrifying. The Germans had killed 10 men to stop him. If he stopped now, those 10 men died for nothing. If he stopped now, the fear worked. Reinhardt had made a calculation. He traded 10 Polish lives for the safety of his trains.

Yoseph sat up in bed. He looked at the moon. He couldn’t bring the dead back, but he could make the calculation too expensive for the Germans to pay. He wasn’t fighting for victory anymore. He was fighting for revenge. He took the lens out from under his mattress. He cleaned it. “I won’t miss,” he whispered to the dark. “And I won’t stop.

” But Reinhardt was waiting. The investigator had realized that random reprisals weren’t working. He needed to catch the ghost in the act. Reinhardt had brought in new equipment, high-powered binoculars, sound ranging microphones, and he had a theory. He had noticed something in the reports. The bridge attack happened at 2:14 p.m.

The curve attack happened at 11:42 a.m. Both times, the sun was at a specific azimuth. Reinhardt sat in his office drawing lines on a map. He traced the angle of the sunlight. He looked at the topography. “He’s not using explosives,” Reinhardt muttered to himself, lighting a cigarette. “He’s using the light.

” It sounded insane, but it was the only thing that fit, Reinhardt circled a spot on the map, a high ridge overlooking the Black Forest Straight. It was the only spot with the right elevation and sun angle for the next scheduled fuel transport. Tomorrow, Reinhardt said, “We will be watching the sun.” Ysef was already packing his bag. He didn’t know Reinhardt was waiting.

He didn’t know he was walking into a trap. He only knew that tomorrow was a clear day. And the trains had to burn. June 21st, 1943. The summer solstice, the longest day of the year. For Obertorm Furer Reinhardt, it was the perfect day for a trap. He had deployed his men not along the tracks, but in the forest itself.

He had placed snipers in the trees, camouflaged in green netting. He had set up a command post on a hill opposite the black forest straight. He wasn’t watching the train. He was watching the ridges. He was watching the sun. Wait for the glint, he told his best marksman, a veteran named Müller. You are looking for a reflection.

Glass, a mirror, anything that catches the light. At 100 p.m., the sun was high and cruel. The heat shimmerred off the rails. Reinhardt checked his watch. The fuel convoy was due in 14 minutes. 400 m away on the opposite ridge, Ysef was already in position. He was tired. His eyes were sunken. He hadn’t slept in two days.

The image of the hanging baker was burned into his retinas. But he was here because he had to be. This wasn’t about winning anymore. It was about defiance. It was about proving that they couldn’t kill his spirit, even if they killed his neighbors. He wedged the lens into the log. He checked the angle.

This was the longest shot he had ever attempted, 450 m. At this distance, the focal point was microscopic. The margin for error was zero. He heard the train. It was a monster. Double locomotive. 20 cars. 12 of them were tankers. It was heading for the Corsk salient, the site of the biggest tank battle in history. If this fuel didn’t arrive, German panzers would run dry in the middle of the fight. Ysef took a breath.

He steadied his hand. Reinhardt raised his binoculars. He scanned the ridge. “Anything?” “Nothing, sir,” Müller replied, his eye pressed to his telescopic sight. “Just rocks.” The train roared into the straightaway. Ysef caught the sun. He focused the beam. It was a tiny trembling needle of light. He walked it onto the third tanker.

“Come on,” he whispered. “Burn!” Reinhardt saw it. It was a flash. A split-second glint of light on the ridge line. It wasn’t natural. It was too sharp, too bright. Contact! Reinhardt screamed. Sector 4, the gray rocks, fire. Müller didn’t hesitate. He pulled the trigger. Crack. The bullet slammed into the rock 6 in from Ysef’s face.

Stone shards sprayed into his eyes. Yseph flinched. He jerked back. The lens slipped. I see him, Müller yelled. It’s a child. He’s running. Kill him. Reinhardt roared. Ysef grabbed the lens and rolled. Bullets chewed up the dirt where he had been lying a second ago. Zip, zip, zip. They were hunting him.

He scrambled on his hands and knees, sliding down the back of the ridge. But he had left something behind. The beam. For those three seconds before the first bullet hit, the beam had been locked on the tanker. The heat had already done its work. The vapor was already boiling.

Just as Müller chambered his second round, the physics took over. The explosion wasn’t a sound. It was a pressure wave that knocked Reinhardt flat on his back. The third tanker didn’t just explode, it vaporized. The blast wave derailed the locomotive at full speed. The entire train, thousands of tons of steel and fuel, jack knifed into a wall of fire that stretched for half a kilometer. The shock wave tore through the trees.

It shook the sniper out of his nest. It shattered the windows of Reinhardt’s staff car. Ysef didn’t look back. He ran. He ran through the chaos, through the smoke that was suddenly filling the valley, hiding him from the scopes. He ran until his legs gave out.

He ran until he collapsed in a ditch, gasping for air, clutching the lens to his chest. He was alive. The train was gone. Reinhardt stood up, dusting off his uniform. He looked at the inferno burning on the tracks. He looked at the empty ridge. He knew he had lost. He knew the sabotur had escaped. But he also knew something else. He had seen the boy. He knew the size of the enemy. “Sweep the villages,” Reinhardt ordered, his voice cold.

“Look for a boy, 12 or 13 years old. Look for burns on his hands. Look for glass. The hunt was on, but nature had one final card to play. 2 days later, the clouds rolled in. Thick, gray, heavy clouds from the Baltic Sea. The temperature dropped. The first snows of 1943 began to fall. The sun disappeared.

Without the sun, Yseph was disarmed. He was just a boy again. He sat by the window, watching the gray sky. He waited for a break in the clouds. It never came. November turned to December. The winter settled in. A brutal freezing blanket that covered Poland in darkness. Reinhardt spent three months searching. He interrogated hundreds of children. He checked every house.

But without new attacks to track, the trail went cold. The German high command grew impatient. They needed Reinhardt on the Eastern Front where the real war was being lost. In January 1944, Reinhardt was reassigned. He left the village, leaving the case file open, marked unsolved. The ghost had vanished into the winter mist.

Ysef never struck again. The war rolled over them. The Soviets came in 1944. The Germans retreated. The occupation ended. Yseph’s grandmother died that spring in her sleep. She never saw peace, but she died knowing her grandson was alive. Ysef buried the lens with her.

He wrapped it in the same dirty rag he had used on the ridges, and he placed it in her cold hands. It was her weapon. It belonged to her. He stood over the grave. He was 14 years old. He was alone. He had killed dozens of men. He had destroyed millions of dollars in equipment. He had changed history. And he walked away into silence. Detroit, Michigan. 1987. A hospital room.

The hum of a ventilator. The smell of antiseptic. An old man lies in the bed. His name is Joseph. He is a retired machinist from the Ford plant. He has three children, seven grandchildren. He loves baseball. He hates fireworks. A young graduate student sits next to him holding a microphone. Tell me about the war, Joseph.

The student asks, “Did you fight?” Joseph coughs. He looks at the ceiling. “For 40 years, he hasn’t said a word.” “Not to his wife. Not to his kids. Who would believe him?” “I didn’t have a gun,” Joseph whispers. His voice is raspy. I had glass. The student frowns. Glass. The sun. Joseph says, closing his eyes. I used the sun. He tells the story.

He talks about the trains, the curve, the bridge, the baker who hanged, the investigator who almost caught him, the student records it all. But later when he transcribes the tape, he shakes his head. Scenile, he writes in his notes. Subject is confusing fantasy with memory. The tape is filed in a box in the university archives.

It collects dust for 30 years. 2018. Dr. Helena Zimmerman, a military historian, is digging through the archives of the German 9th Army. She is looking for logistics reports. She finds a file. Gestapo case Yanadu Saffraven 7B. The phantom sabotur of Zacles. She reads Reinhardt’s notes. Attacks occur only on sunny days.

Evidence suggests focused thermal energy. Suspect is small, possibly a child. Dr. Zimmerman freezes. She remembers a story she heard once. An oral history tape from Detroit. She pulls the records. She cross-references the dates. October 14th, 1942. Train 7 alpha destroyed. Joseph’s tape. I hit the first one in October. It was a Tuesday.

October fid 14th, 1942 was a Tuesday. She checks the weather reports for that day. Clear skies, high visibility. She checks the bridge collapse. May 12th, confirmed. She checks the final attack. June 21st confirmed. Tears prick her eyes. It wasn’t sility. It wasn’t a fantasy. It was the truth. She publishes her paper.

The world finally learns the name of the boy who fought the son. But Joseph is gone. He died two weeks after that interview in 1987. His grave is simple. No medal, no monument, just a name. But if you go to that village in Poland today, if you hike up the ridge overlooking the old railway line, you can still find them. scorched rocks, stones that were burned black, not by fire, but by a heat so intense it vitrified the granite. They are the only witnesses left.

We are taught that war is won by the biggest bombs, by the strongest tanks, by the loudest generals. But history is full of ghosts. It is full of people like Ysef. people who are too small to be seen, too weak to be feared, and too desperate to surrender. Yseph proved that you don’t need an army to stop an empire.

You don’t need a weapon to kill a monster. You just need a piece of broken glass. You need the patience of a stone. And you need the courage to stand in the dark and catch the light. This was the story of the sun gun. The impossible true story of the boy who burned the Reich. If you enjoyed this deep dive into the hidden history of World War II, make sure to hit that like button.