November 1943, Morrow River, Valley, Italy. Captain Ernst Vber pressed his back against the cold stone wall of the farmhouse, his breath coming in short bursts that clouded in the freezing air. Three of his men were dead. Not from artillery, not from machine gun fire, just dead.

One moment they were alive, talking about letters from home, and the next moment they simply dropped. No warning, no sound of a shot until after the bullet had already done its work. Weber had been a soldier since Poland in 1939. He knew what combat sounded like. This was different. This was something else entirely.

The first man died at dawn while lighting a cigarette near the observation post. The second fell 3 hours later, killed while carrying ammunition across what should have been safe ground 200 m behind the front line. The third man, Sergeant Klaus Hoffman, a veteran who survived Stalenrad, died while looking through binoculars at the Canadian positions across the valley. The bullet went through his right eye.

Weber found the binoculars later, one lens shattered, blood frozen on the metal frame. The shot had come from somewhere in the hills to the north, but Weber couldn’t see anything there except fog and bare trees. No muzzle flash, no smoke, nothing. His men wouldn’t move now.

12 soldiers huddled in the farmhouse basement, rifles loaded but useless against an enemy they couldn’t see. Young Private Schneider, barely 18 years old, kept whispering the same word over and over. Hexeray, witchcraft. Weber wanted to slap him to restore order, but he wasn’t sure the boy was wrong. How else could you explain it? The Canadians were killing his men from distances that shouldn’t be possible through weather conditions that made normal shooting impossible, with accuracy that seemed to break every rule of warfare. Weber had ever learned. Across the valley, in a shallow

depression hidden among dead grape vines and rocks, Sergeant Harold Marshall lay perfectly still. He had been in this exact position for 6 hours. The cold had stopped bothering him around hour three. That was normal. In Manitoba, where he came from, you learned to ignore cold or you died.

He had spent entire winters tracking wolves through forests where the temperature dropped to 40 below zero. You learned patience. You learned that movement meant death. That the hunter who moved first usually lost. The German soldiers across the valley didn’t understand this yet, but they would. Marshall was 32 years old, which made him ancient compared to most of the men in his unit.

Before the war, he guided hunting parties through the wilderness north of Lake Winnipeg. Rich men from Toronto and New York paid him to help them find moose and bear. Most of them were terrible hunters. They talked too much. They moved too much. They expected the animals to simply appear because they wanted them to.

Marshall would watch them waste ammunition on shots they had no chance of making, then complain that the forest was empty. The forest was never empty. You just had to know how to look, how to wait. The Canadian Army didn’t know what to do with Marshall at first. He wasn’t a career soldier. He didn’t fit into the normal structure. He couldn’t march in formation without looking awkward.

Other sergeants made jokes about the quiet Indian guide from the frozen north. That’s what they called him. Even though Marshall was white and had never claimed to be anything else. But he had learned tracking methods from cre hunters who worked the trap lines near his cabin. He knew how to read wind and terrain.

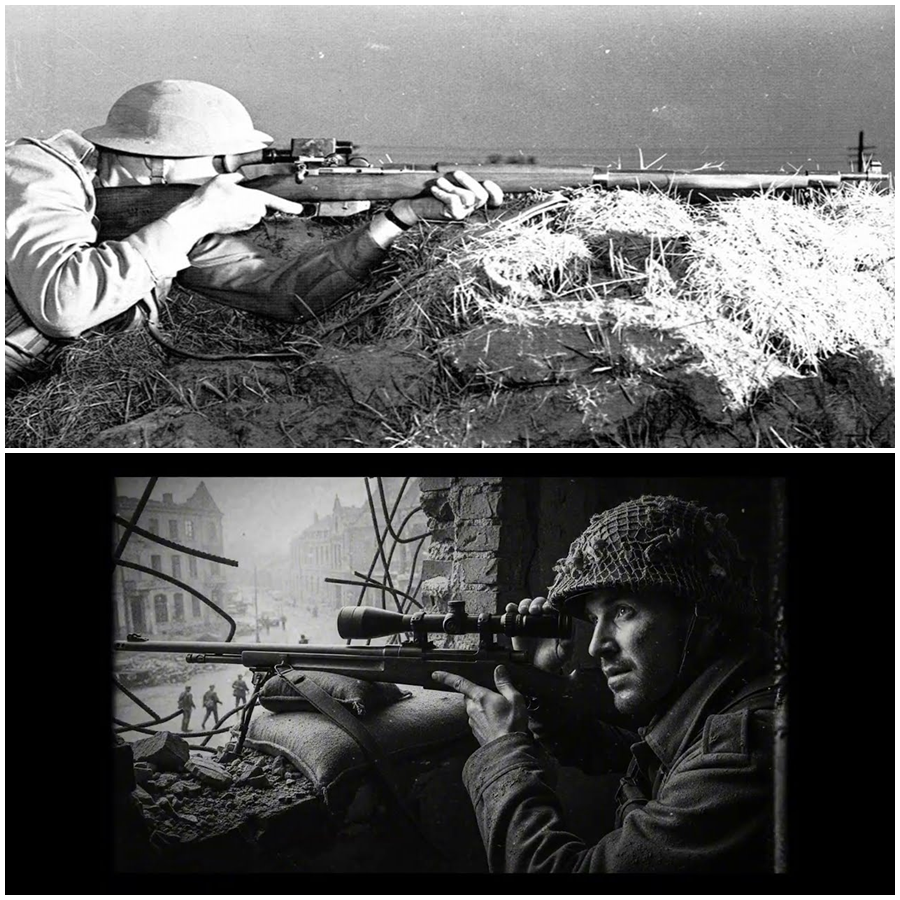

He knew how to become invisible. Then someone gave him a rifle and asked him to shoot. Marshall put five bullets through the center of a target at 400 m. The range officer assumed it was luck. Marshall did it again and again. He never missed. Not because he was naturally talented, though he was, but because he never took a shot unless he was absolutely certain.

In the woods, ammunition was expensive and heavy. You didn’t waste bullets. You waited for the perfect moment, and then you made it count. The British army had sniper programs, but they were small and disorganized. The Americans were still figuring out what a sniper even was. Most commanders thought of sniping as something scouts did when they had extra time, not as a real military strategy.

When Marshall suggested using snipers differently as a weapon of terror rather than just reconnaissance, his first company commander laughed at him. Why waste a trained soldier on single targets when you could use artillery to kill dozens? Why spend hours setting up one shot when you could fire a 100 bullets from a machine gun? Marshall tried to explain. A machine gun made noise.

Artillery made even more noise. The enemy knew where you were and could shoot back. But a sniper, a patient sniper who took one perfect shot and then disappeared created fear. Not just fear of dying, but fear of the unknown. Fear of an enemy you couldn’t see, couldn’t hear, couldn’t fight. That kind of fear changed how soldiers behaved. It made them hesitant. It made them slow.

It made them easy targets for everyone else. Most officers didn’t listen. But Lieutenant General Guy Simons did. Simons commanded the Canadian forces in Italy, and he understood that this war would be won by whoever adapted fastest to new problems. The Germans were dug into defensive positions that were nearly impossible to attack directly. Every assault cost hundreds of lives.

Traditional tactics weren’t working. Canadian casualties were climbing. Something had to change. So Simons gave Marshall permission to try something new. He authorized the creation of specialized sniper sections trained in extreme patience and long range shooting.

He provided modified Ross rifles, the same weapons Canadian soldiers used in the First World War, weapons that were more accurate than the standard issue Lee Enfield at long distances. He let Marshall choose his own men, hunters, and trappers, and quiet farm boys who understood how to wait. Now, 6 hours into his vigil, Marshall finally saw what he was waiting for.

A German officer appeared at the edge of the farmhouse window, just for a moment, checking on his men, 780 m away, through morning fog, through cold air that made everything shimmer and dance, an impossible shot by every standard measure. Marshall exhaled slowly, let his heartbeat settle, calculated windage based on how the fog moved through the valley, and squeezed the trigger.

The German officer dropped without a sound. Marshall didn’t watch him fall. He was already moving, sliding backward through the grape vines, keeping his body flat against the frozen ground. The first rule of sniping was simple. One shot, then disappear. Never take a second shot from the same position. Never give the enemy a chance to find you.

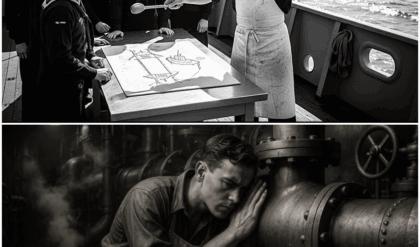

He crawled 30 meters before standing up, then walked calmly back toward Canadian lines like he was taking a morning stroll. His spotter, Private Tommy Chen from Vancouver, followed 10 meters behind, carrying their gear. Back at the forward command post, Marshall cleaned his rifle while Chen recorded the shot in their log book. Distance 780 m.

Conditions: heavy fog with light wind from the northwest. Result: confirmed kill. Enemy officer. Time and position 6 hours and 12 minutes. The log book was Marshall’s idea. Every shot had to be documented with exact measurements. Every condition had to be recorded. This wasn’t guesswork.

This was science married to hunting instinct. You had to know exactly what worked and what didn’t so you could teach others to do the same thing. The rifle Marshall used was a Ross Mark III, a weapon most Canadian soldiers hated. In the First World War, the Ross rifle jammed constantly in muddy trenches.

Soldiers died because their weapons failed at critical moments. The Canadian Army switched to British Lee Enfield rifles after that disaster and the Ross became a symbol of failed Canadian equipment. But Marshall knew something other soldiers didn’t. The Ross rifle was incredibly accurate at long distances.

Its straight pullbolt action was faster and smoother than the Lee Enfield. In clean conditions with proper maintenance, it was probably the most precise rifle in the entire war. Marshall modified his Ross even further. He adjusted the trigger pull to exactly three pounds of pressure. He handloaded his ammunition, measuring each powder charge to the exact grain, ensuring every bullet left the barrel at the same velocity.

He mounted a Canadian-made telescopic site, 3.5 power magnification, and spent hours adjusting it until the crosshairs aligned perfectly at 800 m. Other soldiers thought he was crazy, spending entire afternoon shooting at targets, writing down every detail in his notebook. But Marshall understood that precision required preparation.

In the wilderness, the difference between eating and starving often came down to tiny details most people never noticed. The windage calculations were the hardest part. Wind pushed bullets off course, especially at extreme distances. A bullet traveling 800 m took more than a full second to reach its target. In that second, wind could move the bullet several feet left or right.

Marshall learned to read wind by watching how fog moved through valleys, how grass bent on hillsides, how snow drifted around rocks. He created charts showing wind speed and direction for every hour of the day in different types of terrain. Italian mountains had different wind patterns than French fields, which were different from Dutch boulders.

Every location required new calculations. The patient’s doctrine was Marshall’s most important innovation. Most soldiers, when they saw an enemy, wanted to shoot immediately. That’s what training taught them. See the target, acquire the target, eliminate the target fast and aggressive. But Marshall taught his snipers to wait.

Sometimes for hours, sometimes for entire days. You found a good position with clear sight lines and natural camouflage. Then you became part of the landscape. You didn’t move. You barely breathed. You waited until the perfect target appeared at the perfect moment, and only then did you take your shot.

This technique came from hunting predators in Canada. Wolves were smart. If they saw movement, they disappeared. You couldn’t chase them through the forest. You had to find their trails, figure out their patterns, and wait along their path. Sometimes you waited all day and saw nothing. Sometimes you waited 3 days.

But when a wolf finally appeared, walking calmly because it didn’t know you were there, that’s when you took your shot. One bullet, one kill. Then the wolf pack would avoid that area for months, remembering the danger. Marshall wanted the same thing to happen with German soldiers.

He wanted them to fear every open space, every window, every moment of exposure. He wanted them to remember that death could arrive from nowhere at any time without warning. This wasn’t just about killing enemy soldiers. This was about breaking their will to fight. Not everyone agreed with this approach.

Major Richard Thompson, Marshall’s battalion commander, thought the whole program was wasteful. Thompson was a career officer from Halifax who believed in traditional military doctrine, overwhelming firepower, coordinated attacks. Artillery preparation followed by infantry assault. He looked at Marshall’s log book and saw one kill per day, sometimes one kill every two days.

Meanwhile, a single artillery barrage might kill 20 Germans. A machine gun section might kill 50 in a single engagement. Why dedicate trained soldiers to a method that produced such small numbers? Marshall tried to explain the psychological effect. One artillery shell was scary, but soldiers got used to artillery.

They learned to take cover, wait for the barrage to end, then return to their positions. A sniper was different. A sniper meant that nowhere was safe. Standing up could kill you. Looking out a window could kill you. Walking from one building to another could kill you. That kind of constant fear wore down soldiers faster than any amount of artillery. Thompson didn’t buy it.

He wanted to reassign Marshall sniper sections back to regular infantry duty. The argument went up the chain of command until it reached Lieutenant General Simons. Simons asked to see the German intelligence reports that Canadian scouts had captured. The reports told an interesting story. German units facing Canadian sectors were requesting transfers.

Officers were reporting discipline problems and reluctance to man observation posts. Soldiers were wearing their helmets, even in supposedly safe rear areas. Some units were refusing to send out patrols unless absolutely necessary. Simons read these reports and smiled. He authorized expansion of the sniper program. Marshall would train more men. Every Canadian battalion would have dedicated sniper sections.

The program would get priority for equipment and ammunition. Thompson was furious, but orders were orders. The real proof came during the Battle of Ortona in December 1943. The town was a maze of stone buildings and narrow streets, perfect for German defenders.

Canadian infantry was taking heavy casualties, trying to clear houses one by one. Marshall’s sniper section. Just three men positioned themselves in a church bell tower overlooking the main square. For 16 hours, they controlled the entire area. Any German soldier who tried to cross the square died. Any officer who looked out a window died. The Germans couldn’t advance. They couldn’t retreat. They were trapped by three men with rifles.

A captured German lieutenant later told interrogators that his company refused to leave their building because of the ghost in the tower. They couldn’t see the shooter. They couldn’t hear the shots until after bullets had already passed. Men just fell down dead. Some soldiers claimed the Canadians had invented invisible bullets.

Others said it was impossible for anyone to shoot that accurately, that the Canadians must have some kind of new secret weapon. A few, the lieutenant said quietly, believed it was magic. By spring of 1944, German intelligence officers were compiling strange reports from the Italian front. The documents, later captured by Allied forces, told a disturbing story.

In sectors facing British troops, German officer casualties ran about 12% of total deaths. In sectors facing American troops, officer casualties were around 15%. But in sectors facing Canadian troops, officer casualties jumped to 38%. Even stranger, most of these deaths happened at distances beyond 600 m, ranges where normal infantry combat almost never occurred.

The reports called it an anomaly that required investigation. Vermocked commanders began noticing behavioral changes in their troops. Soldiers who transferred from other fronts to face Canadian units quickly adopted new habits. They stopped standing upright, even in rear areas supposedly safe from enemy fire. They refused to use binoculars near windows.

They wore their helmets at all times, even while sleeping. Patrol frequencies in Canadian sectors dropped by more than half compared to other areas of the front. Some units simply refused to send out reconnaissance patrols unless directly ordered by officers. And even then, soldiers volunteered reluctantly. One German, private, captured near Casino in March 1944, told his interrogators a story that seemed impossible.

His squad had been pinned down in a farm building for 2 days by a single Canadian shooter they never saw. The shooter killed their sergeant on the first morning from somewhere across a valley filled with morning fog so thick the private couldn’t see 50 m. 3 hours later another man died while trying to reach their radio. The bullet came through a window opening barely 30 cm wide.

That afternoon their corporal was hit while hiding behind a stone wall that should have provided complete cover. The private swore the bullet curved around the wall, which he knew was impossible, but he saw his corporal fall and couldn’t explain it any other way. The psychological impact was exactly what Marshall had predicted.

German soldiers in Canadian sectors began seeing snipers everywhere, even when no snipers were present. They fired at shadows. They wasted ammunition, shooting at suspicious bushes and abandoned buildings. They reported sniper positions that didn’t exist. Fear was contagious, spreading through units like disease. New replacements arrived at the front, already terrified, because veteran soldiers had told them stories about the Canadian ghosts who killed from impossible distances through impossible conditions.

The weather often made these fears worse. Italian winters brought heavy fog that rolled through valleys every morning, turning the landscape into gray soup where you couldn’t see beyond your outstretched hand. German soldiers knew that somewhere in that fog, Canadian snipers were watching, waiting, calculating their shots.

The fog would lift suddenly like a curtain being pulled back. And in that moment of exposure, death might arrive. A Lanzer named Otto Becker wrote in his diary about the morning routine in his unit. Nobody moved until the fog cleared completely. Nobody looked outside. Nobody made coffee or smoke cigarettes near windows.

They waited in darkness and silence until the sun burned away the mist, and only then did they risk movement. Even then they moved quickly, staying low, trusting nothing. By summer 1944, when Canadian forces moved to France for the Normandy campaign, their reputation preceded them.

German units receiving orders to face Canadian sectors knew what was coming. Divisional commanders requested extra counter sniper teams. Some units tried to develop their own long range shooting programs, training men to match Canadian techniques. But the German approach to sniping was fundamentally different.

German snipers were taught to take multiple shots, to keep pressure on enemy positions, to work in pairs and cover large areas. They were aggressive hunters. Canadian snipers were ambush predators. They took one perfect shot, then vanished like smoke. The difference showed in the numbers. German snipers in Normandy averaged 15 to 20 shots per day.

Canadian snipers averaged one to three shots per day, but German snipers gave away their positions and often died within 24 hours of deployment. Canadian snipers operated for weeks or months without being located. A single Canadian sniper section could control an area of several square kilometers, making entire roads unusable and forcing German units to move only at night.

Corporal James Wallace became something of a legend during the Normandy fighting. Wallace was a farm boy from Saskatchewan who could shoot the head off a gopher at 300 yards before he was 12 years old. He had eyes like a hawk and hands that never shook even under pressure. In June 1944, near the village of Norbisa, Wallace spotted a German artillery observer working from a church steeple 850 m away.

The observer was directing fire onto Canadian positions, calling in coordinates that were killing men with every shell. The steeple had a small opening, maybe 40 cm across, partially blocked by broken stones. The observer only appeared for seconds at a time, looking through binoculars, then ducking back into cover.

Wallace waited for 40 minutes. His rifle trained on that small opening, his breathing slow and steady. The morning was overcast with shifting winds that changed direction every few minutes. Finally, the observer appeared again, and in that instant, Wallace fired. The bullet traveled nearly a full kilometer, rising and falling in a perfect arc, pushed slightly left by the wind, then right as the wind shifted before entering the steeple opening and striking the observer in the chest. German records later captured from that

artillery unit noted that their forward observer was killed by enemy fire at 0940 hours. Range and method unknown. Shot described as impossible given weather and distance. The Germans tried to counter Canadian snipers with their own specialists.

They brought in experienced shooters from the Eastern Front, men who had survived years fighting in Russia. They equipped them with excellent scopes and gave them priority for ammunition. They set up elaborate camouflaged positions with multiple firing ports and escape routes. But it didn’t work. Canadian snipers had one crucial advantage that German training couldn’t replicate. Patience. Absolute inhuman patience.

A German sniper might wait 3 hours for a shot. A Canadian sniper would wait 3 days. German snipers worked on schedules with expectations about daily targets and results. Canadian snipers had no schedules. They took shots only when conditions were perfect and the target was worth the exposure.

This meant that German counter snipers often revealed themselves first, frustrated by waiting, eager to prove their worth. and when they revealed themselves, they died. The myth grew with each passing month. Soldiers told stories that became more elaborate with each retelling. They spoke of Canadian snipers who could shoot through solid walls, who could see in complete darkness, who knew where every German soldier was at all times.

Some stories claim the Canadians used magic learned from Indian tribes in the frozen north. Others said the British had given them experimental rifles that fired bullets controlled by radio signals. A few soldiers, usually late at night after too much schnops, whispered that the Canadians had made deals with something old and dark that lived in their endless forests, trading their souls for supernatural accuracy.

The truth was simpler, but somehow more frightening. The Canadians were just men. They used ordinary rifles with ordinary bullets. They followed laws of physics and mathematics. But they had mastered their craft with a completeness that seemed impossible to those who faced them. They had turned patience into a weapon sharper than any bayonet.

They had learned to become invisible by staying perfectly still. They had discovered that in modern warfare, the most terrifying thing wasn’t a machine gun or a tank or an airplane. It was a single man who could kill you from a distance so great you never knew he was there and who would wait forever for the perfect moment to pull the trigger.

The war ended in May 1945, but the Canadian sniper doctrine didn’t end with it. Officers from Britain and America requested access to Canadian training materials. They wanted to understand how a relatively small army had developed techniques that terrified one of the most professional military forces in history. The Canadian Army sent instructors to Britain and the United States.

Men like Marshall and Wallace who spent months teaching the patients doctrine to new generations of soldiers. The lessons learned in Italian fog and French hedros became the foundation for every modern sniper program that followed. By the time the Korean War started in 1950, every major military force had adopted some version of Canadian methods. The one shot, one kill philosophy replaced older ideas about volume of fire.

Training programs emphasized patience over aggression, precision over speed. Snipers were no longer treated as scouts with rifles, but as specialized weapons that could shape entire battles. A single well-trained sniper team could control a mountain pass or a city street, forcing enemy forces to change their plans or die trying to execute them.

The psychological warfare aspect, the creation of fear through invisible threat became standard military doctrine taught in every war college. Marshall himself never liked talking about the war. He returned to Manitoba in late 1945, received his discharge papers, and went back to guiding hunting parties through the wilderness. People in his town knew he had been a soldier, but most didn’t know the details.

He didn’t tell stories at the local bar. He didn’t attend veteran reunions. When people asked what he did during the war, he usually said he was a scout and changed the subject. His wife Margaret knew some of it because she held him during nightmares when he woke up gasping, seeing faces he had watched through his scope in that moment before he pulled the trigger.

But even she didn’t know the full count. Marshall never told anyone the total number, and he burned his log book in the woods stove one cold January morning in 1946. The Canadian government gave Marshall a medal for his service, the military medal for bravery and action. The citation mentioned extraordinary courage under fire and exceptional skill in reconnaissance operations.

It didn’t mention that he had personally killed more than 80 enemy soldiers or that German intelligence had offered a substantial reward for his capture or that some Vermach unit specifically requested transfer away from sectors where Marshall operated. The military kept those details classified for decades, not because they were embarrassed, but because they understood that what Marshall had done went beyond normal combat.

He had become something other than a soldier. He had become fear itself. Given form and purpose, Wallace had a different path after the war. He stayed in the military, becoming an instructor at Canadian Army sniper schools. He taught thousands of soldiers over 20 years, passing on the techniques he and Marshall had developed.

Wallace was patient with students who struggled, understanding that not everyone had the temperament for this kind of work. You couldn’t force someone to lie motionless for 10 hours. You couldn’t teach someone to ignore cold and hunger and the desperate need to move. Some people had it naturally, the same way some people could paint or sing or build things with their hands. Others never developed it, no matter how hard they tried.

The soldiers Wallace trained went to Korea, then Vietnam, then dozens of smaller conflicts around the world. They carried Canadian techniques into jungles and deserts and mountains, adapting Marshall’s core principles to new environments. The fundamentals never changed.

Patience, precision, one shot, then disappear. The technology improved over decades. Better scopes, better rifles, better ammunition. Modern snipers could make shots at distances Marshall never dreamed possible. But the mental discipline, the willingness to wait forever for the perfect moment that came directly from those cold Italian hillsides in 1943.

Marshall died in 1987 at age 76. His obituary in the Winnipeg Free Press mentioned that he had served in World War II and spent his life as a hunting guide. It said he was survived by his wife, three children, and seven grandchildren. It noted that he loved fishing and played fiddle at local dances.

The obituary was four paragraphs long and never mentioned that Harold Marshall had changed military history. The German soldiers who feared his name were mostly dead by then. Anyway, old men scattered across Europe who sometimes woke at night remembering the fog and the silence and the sudden incomprehensible death that arrived from nowhere.

The legend of Canadian snipers in World War II eventually became historical fact studied in militarymies and documented in official histories. Researchers found the German intelligence reports that spoke of supernatural accuracy and impossible shots. They interviewed veterans on both sides who confirmed the stories. They discovered that Canadian sniper sections had some of the highest killto casualty ratios of any military unit in the entire war.

The numbers were remarkable, almost unbelievable, but they were real. The myths that German soldiers whispered about in their trenches turned out to be true, just not supernatural. Modern military forces still use variations of Canadian doctrine. Special operation snipers train for months to develop the patience and precision that Marshall taught. They study wind and weather and terrain with the same obsessive detail.

They practice staying motionless for hours, learning to ignore pain and discomfort and boredom. They understand that sniping isn’t really about shooting. It’s about waiting. It’s about becoming part of the landscape so completely that you cease to exist as a separate thing. It’s about finding that perfect moment when the target appears and the conditions align and your breathing settles and your heartbeat slows and everything becomes simple and clear.

What the German soldiers faced in Italy and France wasn’t witchcraft. It was something more fundamental and somehow more terrifying. It was the result of taking ancient human skills, abilities that our ancestors used to survive in harsh environments where mistakes meant death, and applying them to modern warfare with industrial precision.

Marshall and the men he trained were hunters in the oldest and purest sense. They knew how to read landscapes that others looked at but didn’t truly see. They understood patience at a level most people never experience. They could turn themselves into extensions of their rifles.

Biological machines designed for a single perfect moment of violence. The lesson that story teaches us isn’t about military tactics or equipment or training programs. It’s about the fundamental nature of fear and how it shapes human behavior. The Germans weren’t afraid because Canadian bullets were bigger or faster. They were afraid because they couldn’t understand what they were facing.

They couldn’t see it, couldn’t predict it, couldn’t fight it with any method they knew. The fear came from helplessness, from the knowledge that all their training and experience and courage meant nothing against an enemy who refused to play by the rules they understood. In our modern world of satellite surveillance and drone strikes and guided missiles, there’s something almost haunting about remembering when warfare’s most feared weapon was a single human being with a rifle.

One man lying in frozen mud or behind a stone wall or in a church tower, waiting with infinite patience for one perfect shot. The technology we have now is more powerful, more precise, more deadly. But it’s not more frightening because machines don’t create myths. Machines don’t make enemy soldiers question reality.

Machines don’t force entire armies to change how they think about combat. What Harold Marshall and James Wallace and dozens of other quiet Canadian hunters did in World War II was prove that sometimes the oldest skills are still the most effective. Sometimes patience is more powerful than firepower.

Sometimes one perfectly aimed shot creates more fear than a thousand bullets fired in haste. The Germans called them ghosts and whispered about witchcraft because they couldn’t accept the simpler truth. They were facing men who had mastered their craft so completely that they seemed to exist outside normal human limitations. And that mastery, that absolute commitment to perfection in a single deadly skill was more terrifying than any magic could ever.