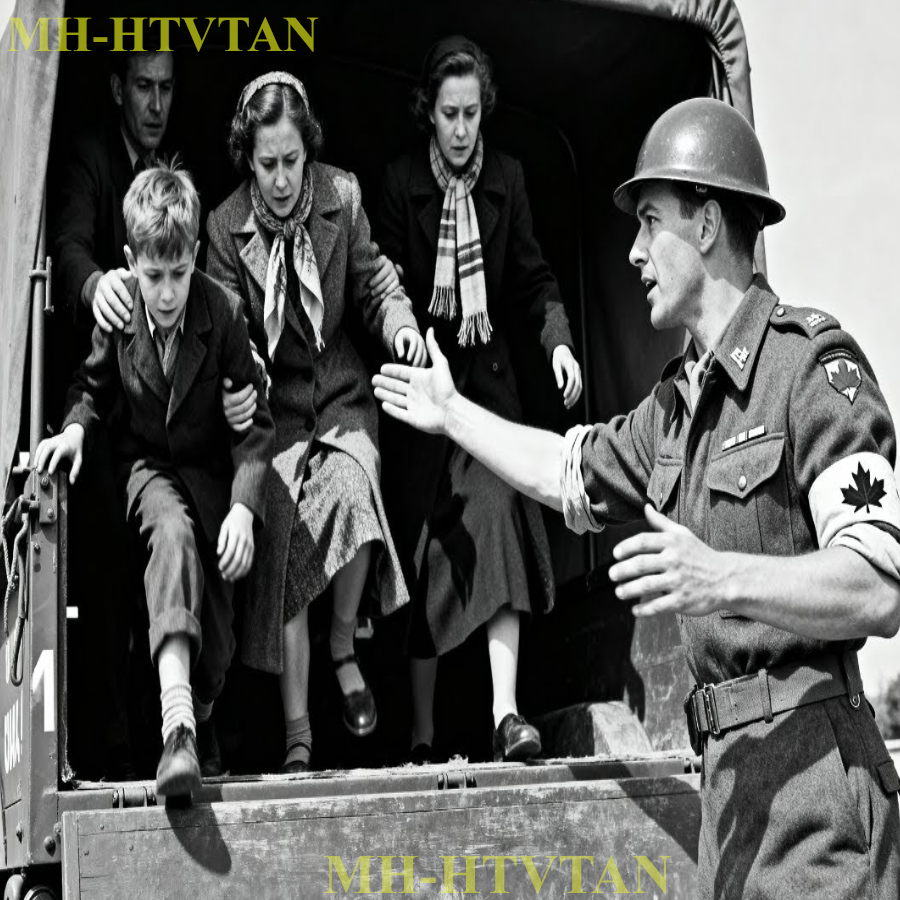

April 1945, Bergen Bellson camp, Germany. British tanks rolled through the gates, finding thousands of Jews and prisoners who had survived Nazi extermination and concentration camps across Europe. Instead of liberation, they found hell on earth.

The smell hit the soldiers first, a thick wall of death and disease that made grown men fall to their knees and vomit. Bodies lay stacked like firewood between the barracks. 60,000 people, more skeleton than human, stumbled through mud mixed with human waste. This was Bergen Bellson, and this was liberation. The numbers told a story that words could not. In the first week after British and Canadian forces arrived, 400 people died every single day. Not from Nazi bullets, not from gas chambers.

They died after being saved. They died in the arms of their rescuers. Medical teams worked around the clock, following every protocol, doing everything right according to their training. Yet each morning brought wagons full of fresh corpses. The death count climbed past 2,000, then 3,000, then 4,000. At this rate, British commanders made a dark calculation.

30,000 more would die within the next 2 months, even with the best medical care the Allied forces could provide. The conventional approach seemed obvious to every trained doctor in the camp. Feed the starving slowly, give them clean water, treat their diseases, keep them warm and comfortable, let their bodies recover at a natural pace.

This was medical science proven over decades of practice. Army doctors had saved thousands of wounded soldiers using these exact methods. There was no reason it should not work here. But it was not working. Prisoners who ate their first real meal in months died within hours. Their shrunken stomachs unable to handle the food.

Others drank too much water too fast and their heart simply stopped. Typhus spread through the barracks faster than doctors could treat it. The medicine was right. The food was right. The water was clean. Everything was being done correctly. Yet, people kept dying in numbers that shocked even hardened combat veterans.

Senior medical officers held meeting after meeting in their command tents. They reviewed charts and discussed treatment plans. They brought in more supplies, more doctors, more nurses. Nothing changed. A British colonel stood before his staff and said the words nobody wanted to hear. These losses are inevitable.

Given the condition these people are in, we should consider ourselves fortunate if half of them survive. We are doing all we can do. The experts had spoken. The best minds in military medicine had reached their conclusion. 30,000 more deaths were simply the price of liberation. A tragic but unavoidable outcome. The doctors would continue their work, follow their training, and accept what they could not change.

Lieutenant Colonel Ben Dunkelman stood in the mud of Bergen Bellson and refused to accept it. He was 28 years old, a Canadian officer who had fought his way across Europe from D-Day to this miserable place. He was not a doctor. He had no medical training whatsoever. He was a soldier, nothing more. But he was also Jewish, and the people dying in front of him were his people.

Every face reminded him of his grandmother, his cousins, the families he knew back home in Toronto. He watched them die, and something inside him broke. Dunkelman walked through the camp for hours, ignoring the smell, forcing himself to look at everything. He saw the barracks where 50 people shared space meant for 10. He saw the single water pump serving thousands.

He saw the medical tent where doctors treated patients one by one carefully and slowly while hundreds waited outside in the cold. He saw the system and he saw why it was failing. That night he sat in his tent and wrote notes by lamplight. His hand shook, not from cold, but from anger. The military was trying to save individuals when they needed to save a population.

Every protocol, every procedure, every rule in the medical handbook was designed for normal situations. This was not normal. This was 30,000 people dying because the rule book did not have a chapter for hell. The idea came to him fully formed, so simple and so dangerous that he almost dismissed it himself. Move them, all of them.

Get them out of this death trap and spread them across a dozen locations where they could be properly cared for. Move the sickest first, the ones most likely to die if they stayed another day in these conditions. Move them fast. Move them now. Move them even if the moving itself was risky. He knew what the doctors would say. Moving critically ill patients was dangerous. The stress of transport could kill them.

Better to keep them stable and treat them where they were. This was basic medical knowledge taught to every firstear nursing student. Dunlman looked at his notes. 400 deaths per day. That was the cost of keeping them stable. That was the price of following the rules. He made his decision. tomorrow. He would present his plan to the senior officers.

He expected them to laugh at him, maybe threaten him with discipline for wasting their time. He was just a combat officer with a crazy idea, going up against trained medical experts who had forgotten more about medicine than he would ever know. But he had one advantage the experts did not have. He had nothing to lose.

The doctors had their reputations, their protocols, their professional pride. Dunkelman had only the faces of the dying and the unshakable belief that watching people die while following the rules was not medicine. It was just slow murder with paperwork. The lamp flickered in his tent. Outside another night fell on Bergen Bellson. In the morning, 400 more would be dead unless someone did something impossible.

The next morning, Dunkelman walked into the command meeting with a folder full of numbers and a plan that would get him court marshaled. The tent was packed with British officers, medical staff, and logistics commanders. Maps covered every table.

Charts showed death rates climbing like a fever that would not break. He waited for his turn to speak, watching seasoned doctors shake their heads at problems that had no solutions. When he stood up, the room went quiet. He was the junior officer here, the Canadian with no medical background trying to talk to experts. He opened his folder and began, “We need to move 34,000 people out of this camp within 72 hours.

” The silence broke into laughter, then angry murmurss, then outright dismissal. A British medical colonel stood up, his face red. You want to move dying patients? You will kill them faster than the typhus. Sit down, Lieutenant Colonel. Leave medicine to the doctors. Dunkelman did not sit down. He pulled out his first page of calculations. Right now, 400 people die here every day. That is a 12% daily death rate.

If we move them to clean facilities with proper spacing, even if we lose 3% during transport, we still save 9%. That is 360 lives per day. Every day we wait, we lose those lives. His voice was steady, but his hands gripped the folder tight enough to crumple the pages. The medical staff pushed back hard.

Moving critical patients required ambulances, trained transport teams, proper equipment. They had none of that. The roads were damaged from war. The weather was cold and wet. Patients would die in the backs of trucks, bouncing over rough roads, bleeding out or going into shock before reaching any destination. It was madness. It was logistically impossible.

It was medically irresponsible. Dunkelman asked for one chance to prove his theory. Give me 500 of the sickest patients. Give me whatever trucks you can spare. Let me move them 15 km to the nearest town with intact buildings. If I am wrong, I will never question medical decisions again.

The room erupted in arguments. Finally, a single voice cut through the noise. Brigadier Glenn Hughes, deputy director of medical services, stepped forward. He was a career military doctor who had seen every kind of battlefield horror. He looked at Dunlman, then at the death rate charts, then back at Dunlman. You get your test, 500 patients, 24 hours to show results.

If your death rate is higher than ours, this conversation ends forever. The next morning, Dunkelman commandeered every vehicle he could find. German army trucks, abandoned ambulances, even a few civilian buses left behind in the chaos. He gathered medical orderlys, nurses, and volunteers who were willing to try something insane. The plan was precise.

Each patient would get exactly 1,200 calories of food before transport spread over six small meals. Water would be rationed at half a liter every two hours. No exceptions. Bodies needed fuel before they could handle the stress of movement. They loaded the first truck at dawn. Patients so thin their bones showed through skin-like shadows. Many could not walk.

Volunteers carried them on stretchers, moving as gently as possible over ground that offered no gentleness. Each truck held 20 people packed with blankets and hot water bottles. Medical staff rode along, monitoring vital signs, ready to stop if anyone crashed. The 15 km journey took 3 hours. Trucks moved at walking speed over roads cratered by bombs and tanks.

Every bump brought gasps of pain from the cargo beds. Twice they had to stop when patients needed emergency care. Dunkelman rode in the lead vehicle, checking his watch every few minutes, calculating mortality rates in his head like a man counting down to his own execution. They reached the town by noon. Empty German barracks became instant hospitals.

The buildings were cold but dry with real floors and real roofs. Space. That was the miracle Dunkelman was betting everything on. In Bergen Bellson, 50 people shared rooms meant for 10. Here, each patient got their own bed with 3 ft of space on every side, room for air to move, room for disease to not spread like wildfire.

The test results came in after 24 hours. Of the 500 patients moved, 15 had died during or shortly after transport. That was 3% mortality. Back at Bergen Bellson main camp, 60 patients had died from the same starting group of 500 who stayed behind. 12% exactly as the statistics predicted. Dunkelman had just proven that moving dying people was safer than leaving them to die in place. Brigadier Hughes reviewed the numbers three times.

He walked through the new facility, checking on patients, talking to medical staff. The survivors were not healthy, not by any measure, but they were alive. More importantly, they were improving away from the contaminated hell of the main camp. Basic medicine actually worked. Wounds started healing. Fevers broke. Bodies remembered how to fight. Hughes made his decision.

Dunkelman would get his full operation. 200 vehicles, whatever he could grab from German P camps. 2,000 German prisoners of war would be put to work as labor, hauling supplies and setting up facilities. 400 medical personnel would be reassigned to support the operation. The British high command would be informed after it was already happening because asking permission would mean delays and delays meant death.

The logistics were staggering. Dunlman needed to move 34,000 people to 12 different locations within 8 days. That meant over 4,000 people per day. Every location needed beds, food, water, medicine, and staff. They had to convert German barracks, school houses, factories, and warehouses into functioning hospitals overnight.

Supplies had to be tracked down, trucks had to run constantly, and every single patient needed individual care plans. Dunlman worked 20our days sleeping in trucks between convoy runs. He created a system where medical care continued during transport. Nurses rode in every vehicle. Food and water were administered on schedule. Patients were monitored constantly.

The trucks became moving hospitals, keeping people alive during the journey to places where they could actually recover. The first full day of operations moved 8,000 patients. The death rate dropped to 3% across all facilities. Compared to the 12% dying daily in the main camp, this was a revolution. A simple, brutal, beautiful revolution built on the radical idea that sometimes saving lives meant risking lives.

The medical establishment watched in stunned silence as an untrained soldier did what they said could not be done. Dunkelman did not celebrate. He was too busy planning tomorrow’s roots. 34,000 lives were counting on a crazy idea working perfectly for eight days straight. The clock was ticking. The numbers told a story that changed everything. Before Dunlman’s evacuation, Bergen Bellson Main Camp recorded 400 to 500 deaths every single day.

The bodies were stacked outside the medical tents each morning, a grim count that never seemed to shrink no matter how hard the doctors worked. After the evacuation began, deaths across all 12 facilities dropped to 50 to 80 per day, an 85% reduction in mortality. 3,400 lives that would have been lost in just the first week were instead saved by trucks, German barracks, and one man’s refusal to accept the inevitable.

Over 8 days, 187 vehicles made countless trips between Bergen Bellson and the scattered network of improvised hospitals. Dunkelman used every German truck, bus, and ambulance he could commandeer from the defeated army. 2,000 German prisoners of war, men who weeks earlier had been fighting against the Allies now carried Jewish survivors on stretchers and built beds in empty warehouses.

400 medical personnel worked in shifts that blurred together into one endless day of triage, transport, and treatment. The operation moved 34,000 people, the equivalent of emptying a small city in just over a week. British high command did not react with praise. 3 days into the operation, Dunlman received an urgent message to report to headquarters.

He walked into a room full of senior officers who looked at him like he had committed a crime. A general slammed his hand on a desk and demanded to know by what authority Dunkelman had commandeered enemy vehicles, used enemy prisoners for labor, and moved patients against the explicit advice of medical professionals.

“You are not a doctor,” the general said, his voice sharp as broken glass. “You have endangered lives, wasted resources, and created a logistical nightmare. We are considering court marshall for unauthorized use of enemy resources and reckless endangerment. Dunlman stood at attention and said nothing. There was nothing to say.

He had broken rules, ignored chains of command, and made decisions far above his authority. By every military standard, he deserved punishment. But by every human standard, he had saved 28,000 lives compared to the projected death toll. The math was simple, even if the military protocol was not.

Brigadier Hughes arrived at the hearing uninvited and stood beside Dunkelman. He carried a folder thick with medical reports, death certificates, and survival statistics. Hughes was a respected career officer, someone the generals could not easily dismiss. He opened his folder and read the numbers aloud. 12% daily mortality before evacuation, 3% during and after. Projected loss of 30,000 lives by end of May.

Actual loss fewer than 2,000 so far. He looked up from his papers. Court marshall him if you want, but do it after you explain to the world why you punished the man who saved Bergen Bellson. The threat of court marshal faded, but did not disappear. Dunlman continued his work under a cloud of official disapproval, knowing that one major mistake would end not just the operation, but his entire military career. The opposition came from all sides.

Traditional military hospitals and hospital ships sat waiting in ports in rear areas designed to receive stable patients who could survive standard evacuation procedures. These facilities had proper equipment, trained staff, and full medical supplies. They sat mostly empty while Duncle man’s field hospitals operated at 300% capacity in buildings that barely had running water. Medical officers wrote formal complaints.

Dunkelman’s methods were dangerous. They said he was guessing, not practicing medicine. His high survival rates were luck, not skill. Sooner or later, a truck would crash or a facility would be hit with an outbreak, and hundreds would die all at once. Then everyone would see that the proper, slower, more careful approach had been right all along. But the crashes did not come. The outbreaks did not spread.

The death rate kept dropping. The alternative approaches proved less effective in ways that could not be argued away. Hospital ships designed for 200 patients received maybe 50 from Burgon Bellson. All in stable condition, all requiring minimal care. Traditional evacuation to rear area hospitals took weeks to arrange, required extensive paperwork, and could only handle small numbers.

By the time the proper channels processed requests and approved transports, the patients were already dead. Dunkelman’s system was crude and chaotic, but it was fast and it worked. One survivor named Hadasa Rosenoft, who would later become a prominent voice for Holocaust survivors, said years afterward that the difference between the main camp and the evacuation sites was the difference between death and life.

At Bergen Bellson, we were dying with full stomachs because the disease was everywhere. In the satellite camps, we were sick but healing because we could breathe clean air. The young Canadian officer understood what the doctors did not. We needed space more than we needed medicine. The scale of the operation became clear only when someone tried to map all 12 locations and track the supply lines.

Dunlman had created a medical network spanning 50 kilometers connected by dirt roads and staffed by whoever was available. Some facilities were in abandoned German barracks with intact kitchens and showers. Others were in school buildings where children’s desks had been pushed aside to make room for hospital beds. One site was a former factory where machines were moved out and CS were moved in.

Each location received daily deliveries of food, water, medicine, and clean linens, all coordinated through a command post that Dunlman ran from the back of a truck. The morning mist rolled across these improvised hospitals like a soft blanket, carrying the smell of disinfectant and boiled potatoes.

Truck engines rumbled in the distance, bringing the next load of patients or supplies. Yiddish prayers mixed with German commands as PS hauled crates of medicine and survivors strong enough to stand helped care for those still too weak to move. emaciated hands clutched British Army blankets. The rough wool, the first real warmth many had felt in years.

The smell of death slowly, impossibly, began to fade, replaced by the sharp, clean scent of antiseptic, and the earthy smell of real food cooking in real kitchens. Official British reports filed in May 1945 described improved medical coordination and enhanced treatment protocols at Bergen Bellson. They mentioned new satellite facilities and better supply distribution.

They credited senior medical staff with innovative approaches to typhus control and nutritional recovery. Dunlman’s name appeared nowhere in the official record. A junior Canadian officer with no medical training did not fit the narrative of professional military medicine solving an unprecedented crisis. But the survivors knew.

They knew the trucks that came when the doctors said moving them would kill them. They knew the young officer who walked through the facilities every day, checking on patients, yelling at supply sergeants, making sure the food arrived on time. They knew that someone had refused to let them die quietly according to the rules and had instead broken every rule to let them live loudly and stubbornly and against all odds.

34,000 people knew the truth, even if the official reports did not. Weeks later, the war ended and Dunkelman went home to Canada. He did not talk about Bergen Bellson. When people asked about his service, he spoke of combat operations, of D-Day beaches and German towns liberated.

He did not mention the trucks or the dying or the 8 days that saved 34,000 lives. It was not modesty that kept him quiet. It was something deeper, something that happens when a person sees the absolute worst of humanity and then has to live in a world that wants to forget. But the military did not forget what he had proven, even if they forgot his name.

By 1950, NATO adopted mass casualty evacuation protocols based directly on Dunkelman’s methods. The idea was simple but revolutionary. When dealing with catastrophic situations where traditional medicine was failing, move people first and treat them second. Create distance between patients and the source of their suffering. Spread them out. Give them space to heal.

The protocols included specific guidelines. Move the sickest first. Maintain medical care during transport. Establish multiple small facilities instead of one large hospital. These were Dunlman’s innovations now written into official military doctrine. The Korean War tested these new protocols within months of their adoption.

When UN forces retreated south in winter 1950, they faced thousands of wounded soldiers and refugees in desperate conditions. Medical officers remembered Bergen Bellson even if they did not remember who had solved it. They evacuated in mass, moving entire field hospitals overnight, treating patients in vehicles and trains and ships.

The survival rates shocked traditional military doctors who still believed that moving the critically ill was a death sentence. Dunlman’s approach had become standard practice. The new orthodoxy replacing the old. Vietnam saw the same methods applied with helicopters instead of trucks. Wounded soldiers were pulled from jungles and evacuated within minutes to facilities far from combat zones.

MASH units became mobile by design, ready to pack up and relocate whenever the tactical situation demanded. The population health approach, treating groups instead of individuals, saving lives through logistics instead of just medicine, became the foundation of modern combat medicine. Every medevac helicopter, every mobile surgical unit, every rapid evacuation protocol carried echoes of eight days in April 1945 when a Canadian officer proved that sometimes the best medicine is a fast truck and an empty building. Modern

refugee crises adopted the same framework. When camps became overcrowded and disease spread faster than treatment, aid organizations learned to create satellite facilities and spread populations across wider areas. The World Health Organization published guidelines for epidemic response that emphasized rapid patient movement away from contamination sources.

Dunlman’s fingerprints were on every page, though his name appeared nowhere in the citations. Back in Toronto, Dunlman built a successful business career, and raised a family. He was active in the Jewish community, supported Israel, lived a quiet, prosperous life. For nearly 40 years, he barely mentioned Bergen Bellson. When he did speak of it, his voice was flat and factual, describing logistics and death rates as if reading from a distant report about someone else’s life.

The emotional weight of those 8 days stayed locked inside, too heavy to share with people who had not been there. In the 1980s, Holocaust survivors began organizing reunions and memorial events. Some who had been at Bergen Bellson started asking questions. Who was the young Canadian officer who had organized the evacuation? Who had commandeered the trucks and set up the satellite camps? Who had fought with the British command to save them when the doctors said they could not be saved? The search led them to Dunkelman, now an elderly man who seemed surprised that anyone remembered

or cared. The survivors remembered everything. They remembered being carried to trucks when they could not walk. They remembered blankets and warm food and the miracle of clean air in buildings that did not wreak of death. They remembered a young officer with dark circles under his eyes who checked on them personally, who yelled at supply sergeants in multiple languages, who treated them like human beings worth saving instead of problems too difficult to solve.

They wanted to thank him. They wanted the world to know his name. Dunkelman agreed to speak at Holocaust Remembrance events. His talks were brief and uncomfortable, a soldier’s report rather than a speaker’s performance. He spoke of numbers and logistics, of trucks and barracks, and food rations. He avoided drama, refused to make himself a hero, deflected praise back to the medical staff, and volunteers who had done the actual work of caring for patients.

But the survivors knew better. The medical staff had been there before Dunlman arrived, following protocols while 400 people died daily. The change, the revolution, the salvation had come from one man’s refusal to accept expert opinion. When expert opinion meant death, Israel honored him in 1997, long after most of the world had moved on to other stories.

The recognition came quietly without the fanfare given to military heroes or famous rescuers. Canada took even longer to acknowledge what one of its soldiers had accomplished. The official military history mentioned Bergen Bellson’s liberation, but gave Dunkelman a single sentence, a footnote in someone else’s story.

The lesson of Bergen Bellson was not about one man’s heroism. It was about the deadly comfort of orthodoxy. The British doctors who said moving patients would kill them were not wrong because they were bad doctors. They were wrong because they were good doctors following good protocols in a situation where good was not good enough.

They had textbooks and training and decades of medical science supporting their position. Dunkelman had only the evidence of his own eyes and the willingness to be spectacularly wrong if it meant a chance to be miraculously right. Sometimes the rules that exist to save lives become the barriers that prevent saving lives. Sometimes expertise becomes a prison where new ideas cannot breathe.

Sometimes the most important thing a person can do is look at the impossible situation, ignore everyone who explains why nothing can be done and do it anyway. Dunkelman was not smarter than the medical experts. He was not braver than the soldiers who had fought across Europe.

He was simply willing to be called crazy if crazy was what it took to keep 34,000 people alive. History loves to remember the dramatic moments. The gates opening, the camps liberated, the prisoners freed. These are the images that fill textbooks and documentaries. But liberation is not a moment. It is a process. It is trucks and barracks and food rations and medical care and a thousand small logistical decisions that mean the difference between surviving freedom and dying from it.

Dunlman understood that opening the gates was not enough. Someone had to make sure the people who walked through those gates lived long enough to have a future. 34,000 futures were built on the foundation of 8 days in April when conventional wisdom met unconventional action and lost. That is the story Bergen Bellson teaches.

That is the legacy one Canadian soldier left behind. Not that heroes save people, but that sometimes saving people requires the courage to be wrong by every measure except the one that matters most. The measure of lives continuing instead of ending, of hearts beating instead of stopping, of bodies healing in clean spaces instead of dying in contaminated ones.

By that measure, Dunlman was not crazy at all. He was the only sane man in a world that had forgotten what sanity looked