At 0700 on January 15th, 1944, First Lieutenant Frank Taxki walked through the brig at Marine Corps Base Camp Terawa in Hawaii. He was 29 years old, a combat veteran of Guadal Canal in Tarawa, and he was looking for the worst Marines in the Second Marine Division. He found them.

18 men locked in cells for fighting, assault charges, gross insubordination, destruction of military property, the kind of disciplinary problems that got Marines dishonorably discharged. Taxki was not there to punish them. He was there to recruit them. Why? Why would an officer, a combat veteran, walk into a prison, to build an elite military unit? Why would the Marine Corps allow him to recruit men who couldn’t even follow basic orders? The answer was not in Hawaii.

The answer was 2 years earlier in a green hell on an island called Guadal Canal, a place that had forced the United States Marines to break every rule just to survive. The story really begins at 0900 on September 27th, 1942. Lieutenant Colonel William Whailing stood on the churned earth perimeter of Henderson Field watching the jungle. It wasn’t a noble watch. It was a vigil.

He was watching four Marines, their shoulders straining, carry a stretcher draped in a poncho toward the aid station. The poncho was dark with everything. 22 years old. His third patrol this week. He was dead before his squad even found the Japanese position they were looking for. Three more stretchers followed. The jungle had swallowed a seven-man reconnaissance patrol that morning.

Only four came back and they came back broken. This was the fundamental terrifying truth of Guadal Canal in 1942. The Japanese owned the jungle and the jungle was eating the first marine division alive. Two months into the campaign, the situation was a catastrophic failure. American Marines trained for open warfare for frontal assaults on European fields were walking into a green hell they could not comprehend.

They were walking into ambushes they never saw coming. A seven-man patrol would leave the wire. An hour later, two men would crawl back, eyes wide with a terror no training manual had ever prepared them for. The other five vanished. 17 patrols had been erased in 3 weeks. Not defeated, erased. The Japanese soldier, by contrast, moved through the dense, suffocating vegetation like a phantom. They were ghosts. They wore leaves. They tied themselves to treetops.

They lived in spider holes for days. They could lie motionless, covered in mud and insects for 72 hours, waiting for a single marine boot to step in the wrong place. A marine patrol couldn’t see an enemy soldier standing 10 ft away. It was a complete tactical breakdown. Ted Mitsu, snipers, shadows in the canopy, picked off officers and radio operators with chilling precision.

Machine gun nests stayed completely invisible until an entire squad had walked past. And then they would open fire from behind, cutting the patrol in half, trapping them, annihilating them. This was not war. This was extermination. And Lieutenant Colonel William Whailing knew this pattern would kill them all.

The First Marine Division had lost 400 men to Japanese ambushes in September alone. Not in glorious battle, not in charges. They were bled out man by man, patrol by patrol. Standard infantry tactics did not work. Standard Marine doctrine was a death sentence. The Marines needed something different. something the Japanese feared, something invisible.

They needed something the Japanese did not expect. The man watching this disaster unfold was by all accounts a failure himself. Two days earlier, Lieutenant Colonel William Wild Bill Whailing had been relieved of his command as executive officer of the fifth Marine Regiment. There was no combat failure, no cowardice, just personality conflicts with his commanding officer. Whailing was a man who spoke the truth.

He saw the tactical failure. He named it and he was punished for it. He was a professional, an expert in an organization that was rewarding blind adherence to a rule book that was getting men killed. In any other circumstance, an officer in his position, sidelined, disgraced, would have been shipped back to the United States on the next available transport. A black mark on his record. His war over.

But Colonel Gerald Thomas, the divisional chief of staff, knew Whailing. He knew his reputation. This was not just any officer. This was Wild Bill Whailing, a veteran of the First World War. a man who earned a silver star at San Miguel. He was an expert marksman, a legend of precision who had competed for the United States in the 1924 Olympics. Think about that.

In an era before high-tech scopes, this was a man who understood ballistics, wind, and breathing better than perhaps any man on the entire island. Most importantly, whailing understood fieldcraft. He understood hunting. He understood the brutal, patient art of stalking an enemy better than any officer in the division. So, Colonel Thomas kept him on Guadal Canal.

He gave him a simple, desperate order. Think about our jungle problem. Whailing did more than think. He watched. For 3 days, he sat at the edge of the perimeter. He watched patrols leave, confident, loud, heavy with equipment. He counted them. And then he counted how many returned. The mathematics were brutal.

At this rate, the First Marine Division would run out of infantry men. Before the Japanese ran out of jungle, he needed men who could do the impossible. He needed men who could hunt the hunters. Men who understood stalking. Men who could read a bent twig, a disturbed patch of mud, men who could move silently, men who could kill without ever being seen.

On September 29th, Whailing, the disgraced officer, walked into General Alexander Vandergri’s command tent with a proposal that would change the course of the Pacific War. It was not a request. It was a necessity. He said, “General, give me 100 volunteers. Let me organize a specialist scout sniper unit. He wanted men handpicked from marines with hunting backgrounds, outdoorsmen, poachers, even men who were already skilled marksmen. He would not train them for frontal assaults.

He would train them in reconnaissance, in ambush tactics, in invisibility. He would send them into the black heart of the jungle in small two or threeman teams. Their mission not to fight the Japanese. Their mission was to dismantle them, gather intelligence, eliminate officers, locate machine gun nests before the regular patrols advanced.

Vandergrift, a student of history, approved it immediately. The general had studied Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rogers and his Rangers tactics from the French and Indian War. small mobile units operating independently deep behind enemy lines. The idea fit perfectly with their desperate situation on Guadal Canal.

Whailing had one week, one week to find his men and start training. The hunt was on. He started reading service records that night. He wasn’t looking for Marines with perfect discipline. He was looking for specific markers, expert rifle qualification. Obviously rural backgrounds, men from Appalachia, from Montana, from the swamps of Louisiana, men who had hunted deer and boore to put food on the table.

Hunting experience, essential. And then a fourth category, the one that made other officers nervous. Disciplinary records. He looked for records that showed independence, not cowardice. Men who thought for themselves. The kind of Marines who got in trouble for questioning a stupid order, but always completed the mission.

Men who weren’t afraid to be alone. By October 1st, Whailing had identified 43 candidates. He called them to a briefing at Oro 600 on October 2nd. The air was thick, hot. He told them the assignment was 100% voluntary. He told them the casualty rate for this kind of reconnaissance work ran above 50%. He told them they would operate in teams of two or three, sometimes for days behind Japanese lines. No backup, no extraction if things went wrong.

If you were caught, you would die alone. If you were lucky, the Japanese would make it quick. He finished speaking. The silence was heavy. 41 men volunteered immediately. Two men walked away and no one blamed them. Whailing looked at the 41 men standing in front of him. Most were 20 years old or younger. Half had been in combat, less than 2 months.

But they had something. The regular infantry did not. They wanted to hunt. And William Whailing was about to teach them how to become the most feared unit the Japanese would ever face in the Pacific War. His training would create a template, a lethal blueprint, a blueprint that two years later, another Marine officer would discover.

An officer who would take Whailing’s methods and add an even more unusual, more shocking requirement to his recruitment process. a requirement that would forge a legend. But first, the prototype had to be built and it had to be built in blood. Whailing started training on October 3rd.

No manuals existed for what he was building. The Marine Corps had officially disbanded its scout sniper program after World War I. It was considered ungentlemanly. The Japanese had no such illusions. Everything Whailing knew came from experience. 24 years in the core, jungle patrols in Nicaragua, the brutal trench scarred battlefields of France, where he learned a simple, profound lesson.

Invisible soldiers live longer than brave ones. The first lesson was silence. He took his 41 volunteers into the jungle west of Henderson Field. He pointed 100 yards through the dense dripping vegetation. His order, walk from here to there without making a sound. Every single man failed miserably. Equipment rattled. Boots cracked branches. Cantens clinkedked against rifles.

The jungle, which seemed so loud with insects and birds, acted as an amplifier for human sound. A Japanese soldier could hear that clink from 300 yards away. He made them do it again. He made them unlearn how to be a soldier. They removed everything that made noise. They taped down metal dog tags. They taped down sling swivels.

They wrapped cloth around canteen hooks and bayonet handles. They walked in soft sold boots or even barefoot instead of their standardisssue leather heeled boots. After 3 days, three agonizing days of moving one foot per minute, half the men could finally move through the densest vegetation without alerting a Japanese position 200 yd away.

They were learning to be ghosts. Marksmanship came next. Most Marines could hit a man-sized target at 300 yd on a sunny, clear rifle range. But rifle ranges did not have 90° humidity. Rifle ranges did not have driving torrential rain. Rifle ranges did not have wind that gusted through trees, and rifle ranges did not have targets that shot back.

Whailing taught them to read the jungle. He taught them to estimate distance by the size of a known terrain feature like a fern. He taught them to judge wind by watching the speed of the vegetation. He taught them to account for how tropical humidity would affect the trajectory of their bullet, pulling it down over long distances.

He made them fire from uncomfortable positions, lying in thick mud, uphill, downhill. A shot that almost always went high, crouched behind cover that barely concealed them, their hearts pounding. By October 10th, his best shooters, the men who truly listened, could kill a Japanese soldier at 400 yardds with iron sights. It was superhuman and it was exactly what was needed.

But the hard part, the truly hard part was teaching them to think differently. The Marine Corps was built on the squad. 12 men, a clear chain of command. Orders flowed down from officers. Initiative was discouraged. Whailing needed the exact opposite.

He needed teams of two or three, operating independently for days, making life ordeath tactical decisions without asking permission. He needed soldiers who could adapt. When the plan inevitably failed, he trained them in map reading and terrain analysis. Not just how to read a map, but how to see the terrain through the enemy’s eyes.

Where would you put a machine gun? Where is the best ambush position? He taught them how to sketch enemy fortifications from memory, how to estimate troop strength, from the color of campfire smoke or the amount of foot traffic on a trail. These were skills that regular infantry never learned because officers did that thinking for them. Whailing wasn’t just training snipers. He was training 41 new officers.

He was creating 41 independent lethal hunters who could think, move, and kill all on their own. On October 13th, the training ended. Whailing received new orders from General Vandergrift. The division was planning a major offensive across the Matanaka River. Japanese forces had dug in on the western side.

Dug in deep, machine gun nests covered every possible approach. Artillery positions sat hidden, invisible in the jungle canopy. Regular patrols kept getting slaughtered trying to find them. Vandergrift’s order was simple. He wanted whailing to take his new partially trained unproven unit and locate those Japanese positions before the main offensive started. This was it, the test.

Whailing picked his eight best men, the best hunters, the best thinkers. He split them into four twoman teams. He gave each team a specific sector of the riverfront to scout. His orders were precise. Avoid contact if possible. Gather intelligence, sketch the positions, count the guns, count the men, and return.

Then he gave the final order, the one that cemented the reality of their new war. If you get pinned down, you are on your own. There will be no rescue missions. The division cannot afford to lose more men looking for lost scouts. They were expendable and every man knew it. The first team left at 4400 on October 14th.

Two Marines, both from Montana, both had grown up hunting elk in high mountain forests. They moved west along the Matanaka River in total darkness. They didn’t use flashlights. They moved by field, by the sound of the water. For 3 hours, they were ghosts at 071 FEM. They found it, a Japanese artillery position. Four type 92 Howitzers hidden perfectly under camouflage netting. They counted 60 soldiers. They sketched the position.

They counted the ammunition crates and by noon they had returned undetected. The second team found a machine gun nest, a Namboo heavy machine gun overlooking a critical river crossing. They mapped it. The third team mapped the Japanese patrol routes. The fourth team ran into trouble.

They were mapping a trail network when a Japanese patrol appeared. Five soldiers 50 yards away. Walking right at them. The two Marines froze. The two Marines froze. Waited for the patrol to pass. But one Japanese soldier stopped, looked directly at the patch of vegetation where the Marines were hiding, and raised his rifle. The Marine closest to him fired first. A single deafening shot.

The Japanese soldier dropped. His four companions scattered, shouting, disappearing into the jungle. Within 30 seconds, whistles echoed through the trees. Enemy troops, hundreds of them, converging on the sound. The two Marines ran. They ran east back toward marine lines, crashing through vegetation they had moved through silently just hours before.

The Japanese followed. The chase lasted for 40 agonizing minutes. The Marines reached friendly positions, diving over the parapet with 11 enemy soldiers just 200 yd behind them. They were exhausted. They were terrified. But they brought back critical intelligence.

Whailing now had detailed maps of Japanese positions along a two-mile front. Information that regular patrols had failed to gather in two months of trying. Information that had cost dozens of Marine lives. General Vandergrift looked at the maps on October 15th and immediately decisively changed his entire offensive plan. Instead of a suicidal frontal assault into the teeth of those machine guns, he would use the scout teams whailing ghosts to guide flanking maneuvers around the Japanese strong points. Whailing’s unit had proven the concept worked.

It had proven its lethality in just 24 hours. Now Vandergrift wanted more. He told whailing to expand, find another 60 volunteers, form a full company, and prepare for the largest marine offensive of the Guadal Canal campaign. The battle for the Matanaka was coming, and Whailing’s scout snipers would lead the way into the deadliest jungle, fighting the Pacific War had yet seen.

The Matanaka offensive began at Oro 600. Whailing’s scouts moved out 30 minutes before the main assault. Their mission was simple. Infiltrate Japanese lines. Locate command posts and artillery positions. Eliminate officers and radio operators. Create chaos before the main marine infantry even cross the river.

Whailing organized his scouts into a special task force. The unit was officially called the composite battalion. Everyone else called it the whailing group. They crossed the Matanaka River 3 mi upstream from the known Japanese positions. They moved through jungles so dense that visibility dropped to 20 ft. No trails, no maps, just compass bearings and whailings training.

By Oro 800, they had penetrated 2 m behind Japanese lines undetected. The first engagement happened at 092. A whailing group scout team spotted a Japanese command post, a tent, radio equipment, six officers studying maps, 15 soldiers providing security. The scouts waited. They waited until all six officers gathered for their briefing. Then they opened fire from 200 yards.

They killed four officers in the first volley. The remaining Japanese soldiers scattered into the jungle. never finding who shot them. 30 minutes later, another scout team eliminated a forward observer, a man who was calling in deadly artillery strikes on the advancing marine positions. A single shot from 300 yd. The observer dropped.

The Japanese artillery fire stopped instantly. Marine infantry advanced 600 yd before the Japanese gunners even realized their spotter was dead. By noon, the whailing group had effectively encircled the Japanese positions west of the Matanakau. Regular marine battalions attacked from the east while whailing scouts cut off all routes of retreat.

The Japanese forces found themselves trapped between two forces. No escape, no reinforcements. The fighting lasted 4 days. Between October 6th and October 9th, approximately 750 Japanese soldiers died in that encirclement. The Japanese Fourth Infantry Regiment, effectively ceased to exist as a combat unit.

Marine casualties, by contrast, were lighter than in any previous offensive. General Vandergrift credited the scout snipers with changing the entire tactical situation. small teams gathering intelligence, eliminating key targets, disrupting command and control. The Japanese had not expected Marines to fight like this.

They expected frontal assaults, not infiltration, not ambush, not ghosts. Whailing’s methods worked, but they came with a price. On October 8th, Whailing himself took shrapnel from a mortar round. He was evacuated and would spend the next four months recovering. But his program, his legacy survived.

The First Marine Division formally established scout sniper platoon in each infantry regiment. The training became standardized. The selection criteria formalized. Everything William Whailing had created from scratch, from failure, from desperation became official Marine Corps doctrine. His legacy was not just a victory. It was a concept, a template for how Marines could fight differently.

His program became the foundation for all Marine Scout sniper operations through World War II, through Korea, through Vietnam. Two years later, another Marine officer preparing for another bloody invasion read Whailing’s afteraction reports. He studied his training methods.

He studied the success at the Matanakaco and he decided to build something even more aggressive. An elite platoon that would take Whailing’s ideas and add one controversial shocking twist. This officer did not want disciplined marines. He did not want hunters and outdoorsmen. He wanted fighters. He wanted troublemakers. He wanted men who won brawls and ended up in the brig. He was about to create the most legendary and notorious scout sniper unit of the entire Pacific War.

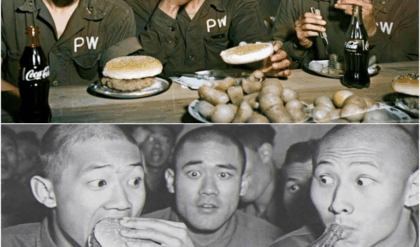

At Uro 700 on January 15th, 1944, First Lieutenant Frank Taxi walked through the brig at Marine Corps base camp Terawa in Hawaii. He was 29 years old. A combat veteran of Guadal Canal and Terawa and he was looking for the worst Marines in the Second Marine Division. He found them 18 men locked in cells for fighting, assault charges, gross insubordination, destruction of military property, the kind of disciplinary problems that got Marines dishonorably discharged.

Taxi was not there to punish them. He was there to recruit them. Three months earlier, Colonel James Rizley had given Taxki an unusual, almost insane order. Form an elite scout sniper platoon for the Sixth Marine regiment. Model it after the British commandos. Train 40 men in reconnaissance and long range killing, but do not recruit from the regular infantry.

Rizley wanted something different. He wanted men who could not follow orders. Men who thought for themselves, men who would survive deep behind enemy lines, where the rulebook tactics that Whailing rewrote still got you killed. Taxki understood the assignment perfectly. He had read William Whailing’s reports.

He knew that Whailing had recruited disciplined hunters, men who happened to have fieldcraft skills. Taxki wanted the opposite. He wanted fighters. His selection criteria was brutally simple. He told the skeptical officers, “When two Marines fight, one wins and one loses. The loser goes to the infirmary. The winner goes to the brrig for assault. Standard marine justice is punishing the wrong man.

The winner, he argued, proved he could handle himself. Proved he would not quit when things got violent.” That was the Marine Taxi wanted on his team. The Brig commander thought he was insane. He told him these men were troublemakers, criminals, the worst discipline cases in the division. Taxki replied, “That is exactly what I need.

” Over 3 weeks, Taxki interviewed 47 Marines with disciplinary records. He asked them why they fought, what they did before the core, whether they could kill a man silently with a knife. 23 of them volunteered. Another 17 came from regular infantry, Marines with expert marksman ratings who had already proven themselves at Terawa. By February 1st, Taxi had his 40 men.

He called them the scout sniper platoon of the sixth marine regiment. The nickname came later after they started stealing everything that wasn’t bolted down on the big island of Hawaii. They became the 40 thieves training began in the dense jungle highlands near Hyo. Taxki used whailing methods as a foundation. Silent movement, long range marksmanship, map reading.

Then he added his own brutal twist. He added British commando tactics, hand-to-hand combat, knife fighting, garota techniques, how to kill a sentry without ever making a sound. He trained them with piano wire garas, teaching them how to roll the wire in glue and crushed glass. The platoon learned to live off the land, hunt wild boar, catch fish, identify edible plants.

These were survival skills for operating for weeks behind enemy lines where resupply was impossible. Equipment was a problem. The Marine Corps issued them World War I era Springfield rifles, outdated rations, no proper camouflage, so they stole better gear. They raided army supply depots at night. They took newer weapons. They stole canned food and cases of whiskey.

They even stole an army captain’s jeep and repainted it marine green. The stealing became legendary. Other marine units called them the 40 thieves, not as an insult, but as a mark of respect. These men operated outside all normal military constraints. They took what they needed to survive.

and their officers looked the other way because Frank Taxki was building something unprecedented, a unit that could hunt Japanese soldiers in their own territory. By May 1944, the 40 thieves were ready and Saipen was coming. 15 square miles of volcanic rock, jagged caves, and dense jungle. 30,000 Japanese defenders dug in, waiting. This was the first invasion of Japanese home territory.

High command expected 70% casualties in the first week and the 40 thieves would go in first days before the main landing. Their mission was simple. scout enemy positions, map defenses, kill officers, and survive long enough to guide the main assault force through the bloodiest invasion of the Pacific War.

At 0530 on June 15th, 1944, Corporal Bill Cannipel crouched in a Higgins boat 300 yd off Saipan’s western shore. He was a member of the 40 Thieves, and he was watching naval bombardment tear apart the beach ahead. The noise was unbelievable. 16-in guns from battleships, 5-in destroyer batteries, rockets from landing craft.

The entire shoreline disappeared under smoke and fire. The Japanese were waiting anyway. The second and fourth marine divisions hit the beach at 040. 8,000 Marines in the first wave. Japanese artillery opened fire immediately. Mortars, machine guns, artillery zeroed in on the landing zones. Marines died before they ever left their boats.

Bodies floated in the surf. Wounded men drowned in 3 ft of water. The 40 thieves landed in the fourth wave. Their mission was different from the regular infantry. While the line companies fought and died for every inch of sand, Taxki’s platoon moved inland. They were looking for Japanese command posts, artillery positions, supply dumps, targets that regular Marines would not reach for days. By noon, the thieves had penetrated half a mile in land.

They found themselves in dense sugarcane fields where visibility dropped to 10 ft. It was perfect terrain for an ambush. Japanese soldiers hid everywhere, in caves, in underground bunkers, in spider holes covered with vegetation. The first silent kill happened at 1300 hours.

Two thieves were scouting a trail when they spotted a Japanese radio operator alone. Setting up an antenna wire, they approached from behind. Piano wire Garote. The operator died without making a sound. They took his maps, his radio codes, and left his body hidden in the sugarcane. Two hours later, another team eliminated a three-man observation post. Knives, no gunfire.

Japanese officers never even knew their forward observers were dead. Their artillery fire became uncoordinated. Marines advanced through the gaps. This was what Taxki had trained them for. Silent killing, operating independently, making tactical decisions without orders. Regular infantry fought setpiece battles. The thieves hunted.

On June 16th, Taxki led a patrol to scout Mount Top Pale, a volcanic peak in central Saipan. Intelligence reports said the Japanese were using the mountain as an observation post. Someone up there was calling artillery strikes down on marine positions. Taxi needed to find them. The patrol reached the base of the mountain. They found a trail leading up the slope, fresh footprints, and bicycle tracks.

The Japanese were using bicycles to move supplies and troops down the mountain. Taxki positioned his best snipers along the trail. Five men with Springfield rifles mounted with unert. He told them to wait. By noon, Japanese soldiers started descending on their bicycles. Officers, couriers, supply runners. They made easy targets. The thieves killed 14 men that afternoon.

They never fired more than one shot per target. They never gave away their position. The Japanese response was predictable. They sent a patrol of 40 soldiers up the trail to find the snipers. Taxi pulled his men back before contact. They melted into the jungle. The Japanese patrol found nothing but empty firing positions and dead bodies. That night, Taxki received new orders.

Division intelligence had located a massive Japanese ammunition depot near Garapan, Saipan’s capital city. Command wanted the thieves to scout the depot, report on its security, and possibly destroy it if the opportunity presented itself. The mission was suicide. Gapan sat 2 miles behind Japanese lines.

Thousands of enemy soldiers were between the marine positions and the city. No support, no backup. If something went wrong, the thieves would be on their own. Taxki picked eight men. The best fighters in the platoon. He told them they would leave at 0200 on June 17th, move through the darkness, scout the depot, and return before dawn.

He did not tell them about the intelligence report he had read just that afternoon. the report that said Japanese commanders had ordered their troops to take no prisoners, that wounded Marines were being used as bait to ambush rescue parties. The thieves were walking into hell. The eight-man patrol left marine lines at 200. No moon, complete darkness.

They moved west through the sugarcane fields toward Gapan. Sergeant Bill Cannipel led the way, reading the terrain by feel, stopping whenever he sensed movement ahead. They reached the outskirts of Garrapan at41. The city had been flattened, but it was still a functioning military base. The ammunition depot sat on the northern edge of town.

Three concrete bunkers surrounded by barbed wire. Guards at each entrance. Taxki counted 16 soldiers. His orders were to scout and report, not to engage, but he saw an opportunity. The bunkers had ventilation shafts, narrow openings in the concrete, just large enough for a satchel charge. If they could place explosives without being detected, they could destroy the entire depot, eliminate tons of Japanese ammunition. He made the decision.

Corporal Rosco Mullins and Private Otto Heeble volunteered. They moved toward the bunker at 0430, crawling the last 100 yards. It took them 20 minutes. Japanese guards walked patrol routes just 30 ft away. Mullins waited until a guard turned his back, lifted the satchel charge, wedged it inside the ventilation opening, and set the timer for 15 minutes.

They were 10 yard from the bunker when a guard spotted them. The Japanese soldier shouted, raising his rifle. Mullins fired first. The guard dropped, but his shout had alerted the entire depot. Whistles echoed through the ruins. Soldiers poured out of buildings. The thieves opened fire from 200 yd away, covering Mullins and Heeble as they ran. The satchel charge detonated at Oro457.

3 minutes early. The explosion tore through the bunker. Secondary explosions followed. Artillery shells, mortar rounds, small arms ammunition. The entire dep depot chain reacted. Explosions continued for 5 minutes. The sky turned orange. Debris rained down across Garrapan. The thieves used the chaos to escape. By 0600, they had crossed back into marine lines.

All eight men. No casualties. They had destroyed the largest ammunition depot in northern Saipan. Division intelligence estimated the explosion eliminated 30% of Japanese artillery ammunition. But the mission had consequences. Japanese commanders now knew Marine scout units were operating deep behind their lines. They increased patrols.

They set ambushes. On June 19th, a thief patrol walked into an ambush near Mount Topo Pale. The Japanese had used two wounded Marines as bait, left them crying for help in an open clearing. When the thief patrol approached, the ambush triggered. The wounded Marines died in the crossfire.

That night, the 40 thieves held an unofficial meeting. No officers present. They voted unanimously. No thief would ever be taken alive. If a man was wounded and unable to escape, the other thieves would ensure his quick death rather than let him be captured and tortured. The war on Saipan had become personal. The next day brought the worst loss the thieves would suffer.

Corporal Martin Dyer led a five-man patrol to scout Japanese artillery. They found the guns, four Type 92s, perfectly hidden. As they began to withdraw, they were ambushed from three directions. Caught in a perfect kill zone, Dyier ordered his men to scatter, to run.

He stayed behind with a Browning automatic rifle, providing covering fire while his team escaped. Three men made it out. Dyier and one other Marine did not. Dyier’s body was never recovered. For his actions, he was postumously awarded the Navy Cross. He had sacrificed himself to ensure his patrol’s survival. By June 26th, news arrived that changed the tactical situation.

Japanese forces were preparing for a massive final banzai charge. Intelligence estimated 3,000 soldiers would attack Marine positions in a single suicidal assault. command wanted the thieves to infiltrate the Japanese assembly areas, locate the officers, and eliminate them before the attack began. It was the most dangerous mission the platoon had received. Taxki briefed his men. He told them the odds.

He told them casualties would be high. He asked for volunteers. All 20 men stepped forward. They moved out at midnight on June 27th. They split into five teams of four. The first officer died at 0230. A Japanese captain studying maps by lamplight. Taxki’s team approached within 50 yards. A single shot from a suppressed Springfield. The captain dropped onto his maps. His guards never even heard the shot.

Over the next 3 hours, the five thief teams eliminated 17 Japanese officers, majors, captains, lieutenants, the entire command structure for the banzai charge. By 5:30, all 20 thieves had returned to marine lines. Zero casualties. The bonsai charge came at 0400 on July 7th. 3,000 Japanese soldiers screaming, bayonets fixed. They hit the marine positions, but the Japanese attack lacked coordination.

Officers who should have directed the assault were dead. Units attacked without support. Communication broke down. What should have been an organized, overwhelming offensive became a chaotic, suicidal charge. Marines held their positions. Artillery and machine gun fire cut down wave after wave. By 0800, the Banszai charge had failed. The battle for Saipan was effectively over.

The 40 thieves had done their job. The platoon finished the Saipan campaign with 27 men, 13 casualties over 21 days of combat. Four dead, nine wounded. They returned to Hawaii in August. The platoon was disbanded in October. The men were distributed to regular infantry units.

The Marine Corps had decided that specialized scout sniper platoon were too expensive in casualties, but their legacy lived. Frank Taxki received the Silver Star. What William Whailing created on Guadal Canal. The 40 thieves perfected on Saipan. Modern Marine Scout snipers trace their lineage directly to these men.

Whailing’s training methods, taxk selection criteria, the fieldcraft, the silent killing, the independence. The scout sniper military occupational specialty was retired in December 2023 after 81 years, but the legacy remains in reconnaissance platoon, in tactics manuals, and in the stories passed down. Stories of Marines who learned that sometimes the deadliest warriors are invisible.