On January 16th, 1943, the SS Skanky was docked quietly in Portland, Oregon. Just 10 weeks old, the brand new Liberty ship had come straight from the Kaiser shipyards. The weather was calm. There was no storm, no threat. Everything seemed normal. Then, out of nowhere, a loud crack echoed across the harbor.

The ship split completely in half. The hole tore from top to bottom like it had been sliced clean through. Crew members rush around as the front and back sections bent away from each other. The ship had broken apart while tied up at the dock. It wasn’t the only one. That same winter, the SS John P gains fell apart in calm waters.

Another ship, the T2 tanker SS Genkity, cracked so badly that the crew jumped overboard in fear. Between 1943 and 1944, over 2,500 Liberty ships reported serious structural problems, cracks, splits, even full-on breakups. At least 19 ships broke in, too, and three completely vanished without sending a single distress call.

These weren’t wartime losses. These were ships failing all on their own. The US had taken a big risk on the Liberty ship program. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, America needed cargo ships. fast. Traditional methods took about 8 months to build just one. That wouldn’t cut it. Industrialist Henry Kaiser, who had never built a ship before, stepped in with a bold promise.

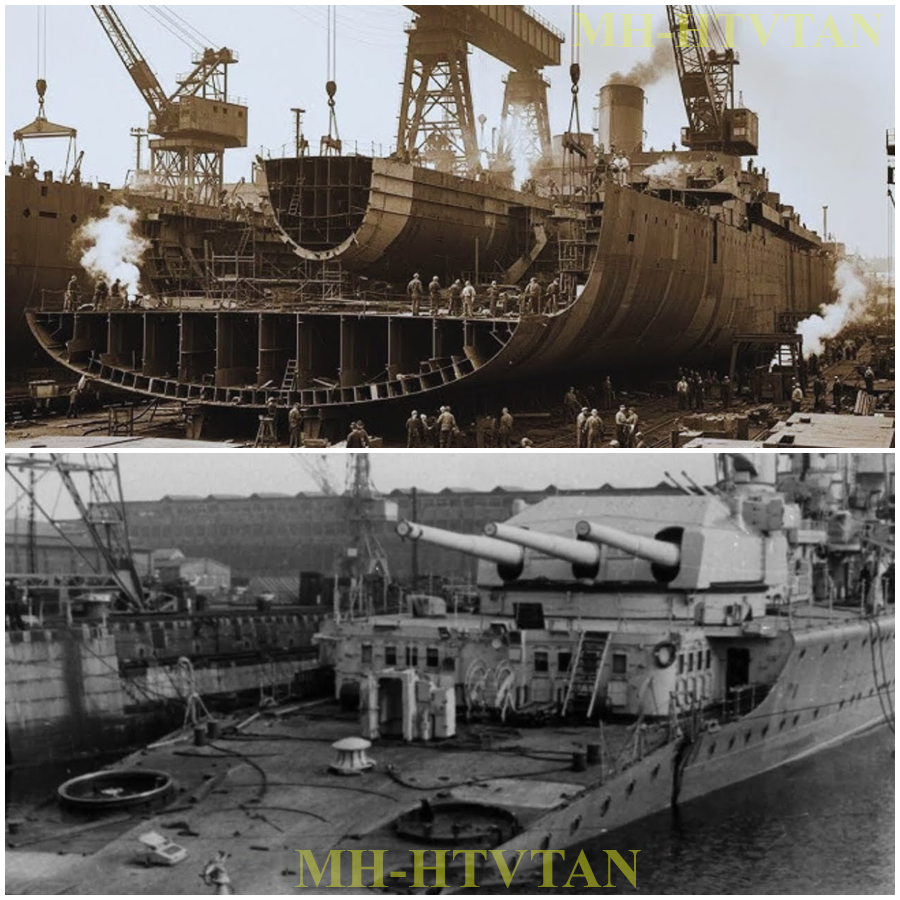

Build cargo ships as quickly as cars on assembly line in weeks, not months. His shipyards in Richmond, California, used new methods. Welding instead of riveting, assembling pre-made parts instead of building everything piece by piece. The process borrowed heavily from car factories in Detroit.

By late 1942, Kaiser shipyards were producing Liberty ships in just 42 days. News reels praised as industrial feet workers, including thousands of women now called Rosie the Riveters, though they were actually welders, were shown rapidly turning steel into ships. One ship, the SS Robert E. Perry, set a record built in just 4 and 1/2 days from start to finish.

These ships help replace losses from German yubot, bringing badly needed cargo back into the Atlantic. But then things started going wrong. Not from enemy attacks, but from sudden unexplained failures. Ships were breaking in calm seas under normal conditions. Experts were puzzled. The welds look fine. The steel pass inspection.

The designs were based on proven British models. Still, Liberty ships were cracking like they were made of glass. Cracks often started at sharp corners around hatches and gun mounts and then spread quickly through the welded steel holes. Once a crack started, it could raise the entire length of ship in seconds. Investigations began.

Experts studied fail holes under microscopes. Engineers recalculated stresses. Inspectors checked the ships from end to end. They considered everything. Steel quality, welding problems, design issues, quality control. Meanwhile, more ships kept breaking apart, and sailors became increasingly afraid of sailing on them. The very thing that made Liberty ships a wartime miracle was turning into a major problem, and nobody could explain why.

Then, a welder on the night shift noticed something no one else had. Bessie Hamill worked at Kaiser’s Richmond yard number three. Like thousands of other women, she had joined the workforce after men left for war. She had been welding for 8 months and started to see a pattern. Welders were doing things in ways that didn’t make sense.

Starting well to the edges and working inward or welding long seams from one end to the other. As the metal cooled, it pulled and warped, locking stress into the structure. Bessie noticed that each weld added stress and made the steel twist slightly. Welders were unintentionally building up tension in the ship’s frame, setting it up for failure later.

She raised her concerns, but her supervisor brushed her off. She wasn’t an engineer, just a welder. The instructions came from higher up, from trained professionals. Still, she didn’t back down. In November 1943, she went over her boss’s head and asked to meet with yard supervisors. That could have gotten her fired, but she came prepared on her own time.

She had welded test plates using different welding orders. The results were clear. Plates welded from the center outward stay flat. Others warped and twisted. The supervisors were skeptical at first, but one agreed to watch a team work. What he saw shock him. The welding process was creating huge amounts of built-in stress.

Every cooling weld added tension. And the way welds were sequenced meant that stress gathered at certain points, especially around hatches and other sharp corners. When these ships hit cold waters in the Atlantic, the steel became brittle. Combined with the locked in stress, that brness made cracks more likely and more dangerous. Bessie’s solution was simple.

Weld from the center out so the stress could spread evenly instead of building up. Alternate welding spots to avoid overheating any one area. Never do long straight welds in one go. Break them up to reduce tension. These weren’t advanced engineering theories. They were hands-on observations from someone who knew how the metal behaved while working with it daily.

By December 1943, her idea made it to Henry Kaiser himself. He faced a tough choice. The Liberty ship program was under scrutiny because of all the failures. Admitting the construction method was a problem, not the materials or welds, meant every ship built so far had a flaw. Fixing it would mean pausing production, retraining welders, and changing the bill process.

But ignoring it could keep putting lives and the war effort at risk. To his credit, Kaiser acted. He ordered testing based on Bessie’s recommendations. A full ship section was pulled from the line and rebuilt using her methods. Engineers who had been searching for answers were now taking cues from a night shift welder. The test confirmed everything.

Ships built with the original welding sequence showed internal stress over 30,000 lbs per square inch at key points. Bessie’s method reduced that stress to around 12,000. The steel and welds were exactly the same, only the sequence changed, yet the results were dramatically better. It finally made sense. Steel isn’t just a solid block.

It’s a material that reacts to heat and cold when it’s welded. It heats up to over 2,500° F, expands, and then contracts as it cools. But if it cools unevenly or is held in place by surrounding cold steel, it stays under stress in cold water. The steel used for Liberty ships lost its flexibility and turn brittle.

Normally, steel bends under pressure, but brittle steel breaks. When that stress met a sharp corner like a hatch, even a small crack could quickly turn into a massive split. These cracks could move at speeds faster than sound, tearing the ship apart in seconds. That’s what happened to the SS Skanky, built in winter, welded using poor sequencing and holding millions of pounds of internal stress.

Her hull couldn’t handle the cold. When the temperature dropped to 28° F, a small crack near a hatch corner turned into a full-blown fracture. The continuous welds gave the crack a clear path, and with no rivets to stop it, the ship split in two. Older ships use rivets, which actually helped. Riveted plates were separate.

If a crack started, it usually stopped at a rivet. Welded ships were different. The seamless welds allowed cracks to run all the way through. The Liberty ship’s square design made things worse. The sharp corners made loading easier, but they also concentrated stress. Kaiser knew what the test results meant. In January 1944, he made a huge decision.

He stopped production at Richmond Yard 2 and shifted focus to a new type of ship, the Victory Ship. This wasn’t just a tweak. It was a total redesign based on what Bessie Hamill had discovered and on the painful lessons learned from the many ships that had already failed. In early 1944, the Allied invasion of Europe was still being planned.

But one thing was already clear. It would need more ships than any operation in history. Every single one counted. Despite that, Henry Kaiser took a massive risk. He committed to using Bessie Hamill’s welding method, redesigning the ships to reduce stress points, improving the steel, and somehow keeping up his already record-breaking production speed.

Other ship builders thought he was out his mind. Congress was watching closely, ready to jump into production started falling behind. But Kaiser and his engineers went back to the drawing board, studying exactly where Liberty ships had failed. They replaced every square corner in the design with rounded ones. Hatch openings that caused so many cracks were redesigned with wide curves to spread out stress more evenly.

They also updated how thick certain parts of the hull and deck were, not to make the ship stronger, but to ensure the stress from welding would spread the right way. Frames inside the ship were moved around to better match the new welding patterns and reduce strain. The steel itself was upgraded.

Kaiser’s team picked a new type of alloy that stayed tough in cold water. They reduced the carbon, added more manganesees, and included just a small amount of nickel, normally reserved for armor. Tests showed even a tiny amount of nickel made the steel much more resistant to cracking. When Kaiser showed that avoiding just one ship loss would cover the extra cost of better steel in 50 ships, the Maritime Commission gave the green light in March 1944. Then came the real challenge.

Retraining tens of thousands of workers. By early 1944, over 90,000 people worked at the Richmond yards, including thousands of welders trained in quick courses that focus on speed. Now, they had to learn stress control, heat management, and exact welding sequences. Kaiser built training schools right inside the shipyards and brought in experienced workers like Hamill to teach others.

Each welder got a numbered card showing exactly where and what order to weld for each section. No guessing, no skipping steps. To make it even easier to control, the ship was broken down into smaller modules built separately in control conditions. A single bow section, for example, could contain 50-minute assemblies, each built to exact standards with heat treatment applied before final assembly to relieve stress.

This modular system allowed welders to follow Hamill center out method in each section without having to work around a full ship. When the first Victory ship ke was laid in February 1944, it took 18 days to build, slower than Liberty Records. Critics jumped on it, claiming the whole program had failed. Kaiser ignored them. He wasn’t watching the clock.

He was watching for cracks. The first two Victory ships had zero stress cracks after construction. Not fewer. None. By April 1944, Richmond Yard 2 looked more like a giant factory than a traditional shipyard. Everything was organized into zones. Each focused on a different part of the ship and brought together like pieces in a puzzle.

Instead of moving the ships, Kaiser used Ford’s assembly line ideas in reverse. The workers and tools moved through fixed stations and time shifts. In the prefab sheds, teams built sections no bigger than 30 ft. Each had its own welding plan with numbered and color-coded welds, always starting in the center and working outward. After every 10 welds, the section went into a special oven that slowly heated and cooled the metal to release stress.

All the steel parts arrived pre-shaped for mills set up just for victory ships. Curved sections came preformed. Bolt holes were already drilled, and frames were preassembled. No more cutting or reshaping on site. This factory prep meant more consistent quality and faster builds. The way the ships were put together also changed.

Instead of starting from the bottom and working up, the new ships were assembled from large modules built in parallel. Engine rooms, cargo holds, bow and stern were all prepared at the same time, then move into place with huge cranes. On May 12th, 1944, Richmond Yard 2 pulled off its biggest assembly yet. 17 major modules making up 85% of full ship were joined together in just 11 hours.

The welders followed the same center out method, but this time they were connecting stress relieve parts, not building stress into them. Through non-stop optimization, Kaiser’s team hit their 5-day target. Supplies were prepositioned during night shifts. Specialized teams handled inspections, alignment, and quality checks.

Cranes ran on tight schedules. Welders worked in time rotations to avoid fatigue. 30 minutes on, 10 minutes off. Kaiser used something called the critical path method to manage the build. He tracked which jobs were slowing others down and move people to keep everything on track. Every delay was recorded and reviewed in daily meetings.

Problems were fixed fast before they turned into bigger issues. Then on June 27th, 1944, Kaiser’s team set a new record. The SS Benjamin Warner victory ship hole number 23 was built from laying the keel to full sea trials in just 5 days and 11 hours. It wasn’t a stripped down prototype. It had weapons, electrical systems, engines, and every well done using Hamill’s stress reducing method.

It passed inspection with no ho cracks. All stress readings were within safe limits. On its first test voyage, it performed flawlessly in conditions that had broken Liberty ships. This ship wasn’t just fast. It was a proof of an entirely new way to build reliable ships quickly and safely. Bessie Hamill’s welding insight change house ships and later infrastructure worldwide were built.

Her idea to sequence welds from the center outward led to the creation of Victory Ships, which fixed the cracking failures that plagued Liberty ships. Stronger steel, curved corners, and crack stopping seams made victory ships faster, safer, and far more reliable. Not one suffered a catastrophic hole failure during the war.

They carried more cargo, survived mines, and boosted crew morale. Hamill’s method became official welding standards, later used in bridges, pipelines, nuclear reactors, and offshore rigs. Yet, she received no recognition, just a supervisor’s letter. Her name never made the textbooks, but her work lives on in every structure built with her techniques.

Hamill showed that how you build matters as much as what you build with, and that frontline workers often see what engineers miss. She asked why ships were breaking and refused. Except that’s just how it is.