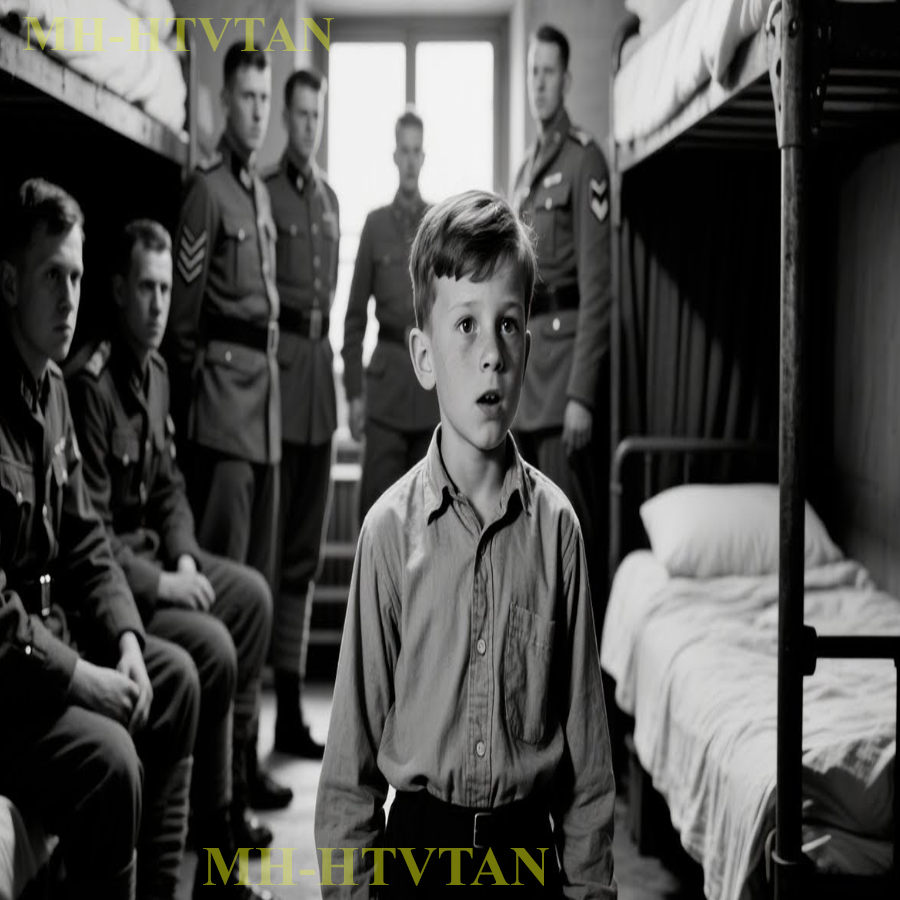

Camp McCain, Mississippi. June 1945. The afternoon sun hung heavy over the processing center where 73 German boys stood in uneven lines, dust coating their shoes and the hems of trousers that had been worn too long. Sergeant Robert Hayes was conducting intake interviews, routine questions translated through an interpreter.

When he reached a boy who looked maybe 14, but could have been older, hunger-aged faces in ways that were hard to measure. The question was simple. Any medical conditions we should know about? The boy’s answer stopped Hayes midnote. I haven’t slept in a bed in 2 years. Then Hayes opened the barracks door. They came by train from New York.

These 73 German boys, aged 12 to 16, who had been swept up in the final chaos of Germany as collapse. Not soldiers exactly, though some had been pressed into auxiliary service in the war, as desperate final months, but not quite civilians either. They existed in the gray space that wars create, too young to be fully culpable, but old enough to have participated in their nation’s catastrophe.

A journey from Europe had taken 3 weeks. Ship across an Atlantic that was finally safe from submarines. Processed through Ellis Island with the same bureaucratic thoroughess applied to all prisoners. Then trained south through an America that seemed impossibly intact. Buildings standing, lights working, people who looked fed and whole.

Wernern Muller was 15 years old and had spent the last two years surviving rather than living. His father had died at Stalingrad. His mother and two sisters had vanished during the firebombing of Hamburg in 1943. He had drifted through the war s final year, attaching himself to retreating military units, sleeping in rubble, eating whatever could be scavenged or stolen, staying ahead of the Soviet advance that consumed Germany from the east.

Captured near Berlin in April, he had been processed through British custody and transferred to American authority, then shipped across the ocean to this place called Mississippi, where the heat felt different from European heat heavier weather, pressing down like a physical weight.

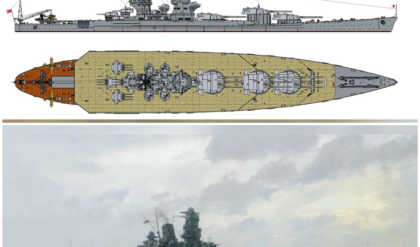

Camp McCain occupied over 40,000 acres of pine forest and red clay. Established in 1942 as a training facility for infantry divisions, it had been partially converted by 1945 to house German hoes. The adult prisoners worked in forests, on farms, in facilities that supported the camp’s operations. But these boys presented a different challenge.

They were prisoners, technically, children of the enemy nation, swept up in the machinery of defeat. But they were also children underfed and traumatized and displaced. The military had protocols for managing adult poise, but few were clear guidelines for managing minors who had no families to repatriate them to. No homes waiting in Germany that hadn’t been reduced to ash and brick fragments.

Sergeant Robert Hayes had been assigned to the youth section of Camp McCain 3 months earlier. He was 34 years old from Minnesota, a high school teacher before the war who had expected to teach again when it ended. Instead, he found himself managing a facility for German boys who spoke no English and carried trauma in their eyes like physical scars.

The processing procedure was routine. Medical examination, documentation of personal history, assessment of any special needs or concerns. Most boys moved through it with blank efficiency, answering questions in monotone German that the interpreter translated into equally monotone English. Wernern reached the processing desk midafter afternoon.

Hayes looked at the boyin to the point of skeletal, wearing clothes that were clean but ill-fitting, eyes that were older than his face. Name: Wernner Mueller. Age 15. Hometown Hamburg. Gone now, family, dead or disappeared. Hayes had heard variations of this story dozens of times? It didn’t get easier. He continued down the form.

Any medical conditions we should know about? Wernern considered the question then in careful German that the interpreter translated. I haven’t slept in a bed in 2 years. Hayes stopped writing, looked up. The interpreter repeated the statement, thinking perhaps Hayes hadn’t heard. Two years? Hayes asked. Yes, Warner confirmed through translation.

Since Hamburg burned floor, rubble, ditches, bunkers, no beds, Hayes set down his pen. What he felt was complicated pity for what this kid had endured. Anger at the war that had done it. uncertainty about how to respond to a statement that was simultaneously devastating and matter of fact. Well, Hayes said finally, “You’ll sleep in a bed tonight.” Wernern’s expression suggested he didn’t quite believe this.

The youth barracks had been modified from standard military housing. Bunk beds instead of cotss. Closer spacing to maximize capacity. Windows fitted with wire mesh that provided ventilation while maintaining security. The walls were bare wood, recently whitewashed. The floor was concrete, swept clean. Each bed had two wool blankets, one pillow with a cotton case, and a foot locker for personal possessions.

By American military standards, it was basic. By the standards of boys who had spent years in war zones, it was luxury verging on incomprehensible. Hayes led Werner’s group 12 boys assigned to barracks 7 through the door. The interior was dim after the bright Mississippi afternoon, dust moes hanging in shafts of light from the windows.

This is your housing, Hayes explained through the interpreter. You’ll be assigned beds, given supplies, and briefed on camp rules. Choose a bunk. The boys stood frozen, staring at rows of beds like they were viewing artifacts in a museum objects from another life. Another reality where people slept on mattresses rather than concrete. Wernern approached the nearest bunk slowly.

He touched the blanket. Wool thick clean. No holes, no stains, no evidence of previous use. He pressed his hand against the mattress. springs gave slightly under pressure. It was real, soft, designed for human comfort rather than just preventing bodies from touching cold ground. Go ahead, Hay said. Sit down. Test it.

Wernern sat carefully as if the bed might collapse or vanish. The mattress supported his weight. The springs creaked slightly. It felt impossible. He laid back, arms at his sides, staring at the ceiling. The other boys watched. Then one by one they began choosing monks, testing mattresses, experiencing the strangeness of furniture designed for rest.

One boy, Otto, 13, from Berlin, began crying. Silent tears running down his face while he gripped the blanket in both hands. He didn’t explain, and no one asked. They all understood. This simple object, a bed, blankets, the promise of sleeping without cold, seeping through from whatever surface you collapsed, unrepresented.

Everything they had lost and thought they would never regain. Hayes watched these enemy children crying over armyisssue bedding and felt something shift in his understanding of what victory meant and what responsibilities it created. That first night, Wernner laid in his assigned bunk and couldn’t sleep. Not because the bed was uncomfortable.

It was the most comfortable surface he had experienced in 2 years, but because comfort felt alien, suspicious, too good to trust. Around him, other boys rustled and shifted. Some slept immediately, exhausted bodies overriding mental resistance. Others lay awake like word, processing the disconnect between expectation and reality. The propaganda had been clear. Americans were enemies, occupiers, people who would starve and humiliate defeated Germans.

Wernern had been prepared for punishment, for deprivation, approximating what Germany had inflicted on others. Instead, beds, blankets, food that was bland but sufficient, guards who seemed more bored than cruel. He thought about Hamburg, the apartment where he had grown up, destroyed in firebombing.

The bed he had slept in as a child, with its thick feather mattress his grandmother had made, burned to nothing in a single night of incendiary destruction. He thought about his mother and sisters, last seen running toward an air raid shelter that had taken a direct hit.

He thought about the two years that followed, sleeping in basement, in destroyed buildings, under bridges, in ditches when there was nothing else. The American bed beneath him felt like mockery and grace in equal measure. Mockery because it revealed how far he had fallen. Grace because it suggested falling could be survived. That basic human dignity could be restored even to enemies.

He finally fell asleep near dawn. His body making the decision his mind couldn’t. When he woke to Revy at 060, he had slept six continuous hours in the same position. more rest than he’d gotten in weeks of fitful shelter sleeping. The days at Camp McCain followed military structure adapted for juvenile detainees.

Morning roll call, breakfast in the messaul, work details that were educational rather than punitive. Afternoon recreation time, dinner, evening study period, lights out at 2,100. The work details included English language instruction, basic mathematics, vocational training in carpentry, and farming. The goal, never explicitly stated, but obvious, was to prepare these boys for repatriation to a Germany that would need rebuilding and would need skilled workers to do it. Wernern was assigned to the carpentry workshop.

The instructor was Corporal James Mitchell, a 30-year-old from Tennessee who had learned woodworking from his grandfather and taught it with patient precision. Mitchell spoke no German. His students spoke no English. Communication happened through demonstration, gesture, and the universal language of showing someone how to properly hold a saw.

On Wer’s third day, Mitchell was demonstrating dovetail joints. Wernern watched, fascinated. Before the war, his father had been a furniture maker. Wernern remembered being very young, watching his father work in the small shop attached to their apartment, the smell of wood shavings and varnish. Mitchell noticed Wernner’s particular attention.

He handed the boy a piece of scrap wood and a handsaw. Show me what you can do. Wernern took the tools with hands that remembered holding similar implements in another life. He measured, marked, cut. The motion came back like muscle, memory surviving trauma. The cut wasn’t perfect.

He was out of practice and working with unfamiliar tools, but it was competent. Mitchell examined the work, nodded approval. Your father teach you this? Wernern didn’t understand the English words, but he understood the tone and gesture. He nodded. Yeah, he said. Vader. Then realizing Mitchell didn’t speak German. Father, Carpenter. Mitchell smiled. Mine too.

He pointed at Wernner, then at himself. Same. We are the same. It was a small moment, barely worth noting in the vast machinery of postwar processing. But Worler felt something shift the first recognition that he and his capttors might share more than their differences. That craft and skill transcended nationality, that a love of woodworking created connection across the gap of enmity. Over weeks, Wernern began to change.

Not traumatically, trauma didn’t heal in neat timelines, but in increments in the accumulation of small securities that created space for something beyond survival. He gained weight. The messaul food was institutional and bland, but it was regular and sufficient. His body began remembering what adequate nutrition felt like, began rebuilding what hunger had stripped away.

He slept every night in the same bed with the same blankets in the same space. No waking to bombing, no needing to relocate because the building was collapsing. No sleeping in shifts to watch for danger. Just sleep 6 to 8 hours nightly. The kind of deep rest that allowed brains to process trauma instead of just filing it away for later.

He learned English slowly, frustratingly, but consistently. Corporal Mitchell taught woodworking terms: saw, hammer, nail, joint, grain, measure. Other guards taught other words. The boys taught each other vocabulary like rations. By August, Wer could construct simple sentences, could ask for things instead of just pointing, could express thoughts beyond immediate needs, and he worked with his hands.

The carpentry workshop became his refuge. Mitchell had recognized Werner’s talent and given him increasingly complex projects. By September, Wernern was building furniture, simple pieces, benches, and tables, but functional and well-made. Each project felt like reclaiming something his father had taught him, like preserving a connection that Hamburg’s destruction had tried to sever. One afternoon, Mitchell called Wernern over to examine a rocking chair.

Wernern had spent 3 weeks constructing. The proportions were right. The joints were sound. The finish was smooth. Mitchell sat in it, rocked gently, nodded approval. This is good work, professional quality. Your father would be proud. Wernern understood enough English now to catch the meaning. He felt his throat tighten.

Father is dead, he said in careful English. Mitchell stood, placed a hand on Wernern’s shoulder. But his teaching isn’t dead. You carry it forward. That matters. Wernern nodded, not trusting his voice. He thought about his father’s workshop in Hamburg, about watching him work, about the future he had imagined where he would learn the trade properly and maybe take over the business someday. That future had been incinerated.

But here, in an American prison camp in Mississippi, something of it survived. In October, Sergeant Hayes called Wernern to his office. Wernern entered nervously, being summoned by authority usually meant trouble. Even in this relatively benign captivity, Hayes gestured to a chair. Sit. No trouble. Just wanted to talk.

Wernern sat, hands folded in his lap, waiting. Hayes had a folder open on his desk. Wernern could see his name on the label, documents filled with information he had provided during processing. Hayes studied the papers, then looked at Wernner. Repatriation is being organized, Hayes said slowly, speaking simply for Warner’s English. You will go back to Germany soon. Probably December.

You understand? Warner understood. Yeah, I understand. Back to Germany. The question is, what will you do there? You have no family. Hamburg is destroyed. You’re 15 years old. What’s your plan? Wernern had no plan. He had been surviving dayto-day for so long that planning felt impossible. Germany, rubble, chaos, no family, no home, no clear path forward. I don’t know, he admitted in English. Just dot dot go.

See what is there? Hayes leans back in his chair. Here’s what I’m thinking. You’re talented. Mitchell says, “You’re the best carpenter he’s seen in years, including adults. That’s a skill Germany will need. Everything is destroyed. They’ll need people who can build.” Wernern nodded. This was true, but overwhelming.

The scale of destruction, the magnitude of rebuilding, it was too large to contemplate. Hayes continued, “Before you go back, we can help you. More training, more practice. We can give you tools to take with you proper carpenters tools. We can provide documentation of your training here. It won’t be much, but it might help you find work when you return. Why? Warner asked.

Why help enemy? Hayes was quiet for a moment. Because the war is over. Because you’re a kid who lost everything. Because teaching you a trade that helps you survive isn’t weakness? It asked what decent people do regardless of what flag someone fought under. Wernern processed this. The logic made sense but contradicted everything he had been taught.

Enemies were supposed to be cruel, punishing, vindictive. These Americans were teaching him skills, feeding him, preparing him for a future. Thank you, Warner said finally. It was inadequate, but all he could manage in English. Hayes waved off the gratitude. Just learn, work hard, build good things when you go home. That’s thanks enough.

November brought cooler weather and preparations for repatriation. The first group of boys was scheduled to ship out in mid December. Wernern was on the manifest, assigned to a transport that would take him back to occupied Germany and whatever awaited there. The carpentry workshop had become his home in ways the barracks never fully did.

Here he felt competent, useful, connected to something larger than just survival. Here he was Wernern the carpenter, not Werner the displaced war orphan. Mitchell had been working on something during Wernern’s off hours. A week before Wernner’s scheduled departure, Mitchell called him over to a workbench where something large sat covered with a tarp. made something for you, Mitchell said. Going away present.

He pulled off the tarp. Underneath a wooden toolbox. Not just any toolbox, a masterpiece of carpentry. Dovetailed corners, smooth finish, fitted interior with specific spaces for specific tools. and inside a complete set of hand tools. Saws, chisels, planes, hammers, measuring tools, everything a carpenter needed to work. Wernern stared. This was impossibly generous.

These were professional tools, expensive, carefully selected. The toolbox alone represented dozens of hours of skilled labor. I can’t, started, too much. I am prisoner. enemy. Mitchell shook his head firmly. You’re a carpenter. I’m a carpenter. We take care of our own. When you get back to Germany, you’ll need tools to work.

Can’t rebuild a country without tools. But no butts. Mitchell’s voice was firm but kind. You earned this. Your work here, your dedication, your talent, you earned it. Take the tools. Build good things. That’s all I ask. Wernern ran his hands over the toolbox, feeling the smooth wood, the precise joints.

His father had owned a toolbox similar to this. It had burned in Hamburg along with everything else. This wasn’t a replacement. Nothing could replace what had been lost. But it was a continuation, a passing of craft from one generation to another across the impossible divide of war.

Thank you, Wernner said in English, then repeated it in German because the English felt insufficient. Danka vand dank Mitchell gripped his shoulder. Go build Germany better than it was. Build it without the hatred that destroyed it. You understand? Wernern understood or was beginning to that craft could be moral. That rebuilding could be redemption. that the opposite of destruction wasn’t just survival but creation.

December 15th, 1945. The morning was cold by Mississippi standards. Frost coating the grass near the barracks. Wernern and 43 other boys prepared for transport. They had been issued travel clothes, American military surplus, adapted for civilian use, clean and warm. Each boy had a small bag for personal possessions.

Wernern’s bag was nearly empty. He owned almost nothing. A few photographs salvaged from Hamburg. A letter from the Red Cross confirming his mother and sister’s presumed deaths. His documentation from Camp McCain. But he carried Mitchell’s toolbox separately, holding it with both hands like the treasure it was.

The boys assembled in the central yard. Guards who had overseen them for months stood at attention. Sergeants Hayes stood at the front preparing to lead them to the trucks that would begin their journey home. Before they left, Hayes addressed them through the interpreter. Short speech translated sentence by sentence. You came here as prisoners. You leave as young men with skills and training.

Germany needs rebuilding. You can be part of that. Take what you learned here, English, carpentry, farming, whatever you studied, and use it to build something better than what was destroyed. He paused, choosing words carefully. This war happened because of hatred and lies. Don’t carry that forward. You’re young enough to create new Germany without old poisons.

Remember that Americans treated you with fairness when they could have chosen cruelty. Remember that enemies can become something else when the fighting stops. The interpreter translated. Some boys nodded. Others stared at the ground. All were processing complicated feelings about leaving captivity that had been unexpectedly humane.

Returning to a homeland that existed only as rubble and memory. Corporal Mitchell appeared beside Wernern. Handed him an envelope. Open it on the ship, he said. Not before. Wernern took it, tucked it carefully into his jacket pocket. Thank you for everything, he said in English. It had improved dramatically over 6 months.

Thank you for learning, Mitchell replied. For showing that teaching matters. Now go teach someone else. The trucks pulled away at 090 hours. Wernern sat in the back, toolbox on his lap, watching Camp McCain disappear into Mississippi pines. He thought about Hamburg, about his father’s workshop, about sleeping in rubble and ditches and believing that beds were luxuries he would never experience again.

He thought about the American bed in Eric’s 7, about Mitchell’s workshop, about Sergeant Hayes treating enemy children with basic decency, because doing so was right rather than required. The war had taken everything. These Americans had given back not everything that was impossible, but something. Tools, skills, the understanding that he could build instead of just survive.

It wasn’t redemption, wasn’t compensation for loss, but it was possibility. And for a 15-year-old who had spent 2 years without hope, possibility felt like grace. On the ship crossing the Atlantic, Wernern remembered the envelope. He opened it carefully, found a letter written in simple English that he could now read with modest comprehension.

Wernern, by the time you read this, you’ll be heading back to Germany. I want you to know something that’s important. My father taught me carpentry. He was patient and skilled and he believed that craft mattered, that building good things was how you contributed to the world. He died in 1938 before this war started, before everything went to hell.

When you came to my workshop, you reminded me why he taught me why skills matter. Why passing knowledge forward is how we survive as people, not just as individuals. You’ve been through things no kid should experience. You’ve lost people in places that can never be replaced. I know the tools I gave you don’t fix that, but maybe they help you build something new.

Germany is going to be hard. Rebuilding will take decades. You’ll see things that make you want to give up. When that happens, remember every building, every chair, every table starts with a single cut, one piece at a time. That’s how you rebuild countries and lives. I’m proud of you. Your father would be proud of you. Go build good things.

Corporal James Mitchell Wormer read the letter three times. Then he folded it carefully and placed it in the toolbox in the special compartment Mitchell had built. He would keep it there for the rest of his life. Bremen, Germany. January 1946. The city was a wasteland. Rubble piled higher than buildings had stood.

Civilians moving through destruction like ghosts, their faces carrying the same hollow exhaustion Wernner recognized from mirrors. Processing through British occupation zones, Wernern presented his papers. The officer reviewing them noticed the American camp documentation. The letter from Mitchell describing Wur’s carpentry training. You have skills, the officer noted. That’s valuable.

We’re setting up trade schools, reconstruction programs. Report to the labor ministry office in Munich. Wernern made his way south. The journey took days, hitching rides with military convoys, walking when no transport was available. everywhere. Destruction.

Cities that had been bombed into submission, infrastructure destroyed, people surviving in basement and ruins. In Munich, the labor ministry office occupied a damaged building that had been partially restored. Wernern presented his documentation. An official reviewed it typed papers from Camp McCain, Mitchell’s letter of recommendation, photos of Warner’s work. You’re 15, the official said.

Where’s your family? Dead or disappeared? The official nodded. This was common enough not to require further discussion. You have housing? No. No. The official made notes. We can assign you to a youth housing facility. You’ll work during the day on reconstruction projects. Attend trade school in the evenings. Pay is minimal but includes housing and food.

Interested? Yes. Warner was assigned to a crew rebuilding apartment blocks in Munich’s destroyed center. The work was hard, the pace relentless. Germany needed housing desperately. Millions were homeless, displaced, living in temporary shelters. Every building reconstructed meant families moving from basement to actual apartments.

Wernern worked with tools Mitchell had given him. The other workers noticed the quality Americanmade, professional grade, better than the salvaged and improvised tools most Germans were using. Where did you get these? His foreman asked. American prison camp, Warner replied. My teacher gave them to me. The foreman examined the toolbox, noted the craftsmanship.

Your teacher was good carpenter. The best, Wernner agreed. Over years, Wernern established himself as a skilled carpenter. By 1950 and 19, he was leading reconstruction crews. By 1955, he had his own small construction company. By 1960, his firm had built over 300 housing units in Munich and surrounding areas. He never forgot Mitchell’s letter.

When hiring apprentices, he looked for boys like he had been displaced, traumatized, without clear futures. He taught them carpentry the way Mitchell had taught him, with patience and precision and the understanding that craft could be redemption. In 1965, Wernern traveled to the United States for a construction trade conference. He detoured to Mississippi. Camp McCain had been deactivated in 1946.

The land returned to civilian use, but he found the approximate location, stood in pine forest where barracks had once been, remembered sleeping in a bed for the first time in 2 years. He tried to locate Mitchell. Military records led him to Tennessee. James Mitchell had returned to carpentry after the war, taught shop class at the same high school he had attended as a boy.

Wernern called, introduced himself, asked if they could meet. Mitchell, now 59, remembered immediately. Wernern, the German kid who could dovetailed joints blind. Of course, I remember. They met in Mitchell’s workshop attached to his house, smelling of wood shavings and varnish, looking remarkably similar to what Wernern remembered from Camp McCain.

Mitchell had aged, hair gray now, hands showing arthritis, but his eyes still held the same patient intelligence. “You kept the tools,” Mitchell observed, seeing Werner’s toolbox. “Use them everyday for 20 years,” Wernern replied in English that was now fluent. “Built over 5,000 housing units with these tools. Taught 50 apprentices, still using them.” Mitchell smiled.

That’s what tools are for, to be used, to be passed forward. They spent the day together talking about carpentry, about the years since the war, about what it meant to teach craft across generations. Mitchell showed Werner current projects.

Wernern showed Mitchell photographs of buildings his company had constructed, apartment blocks, schools, community centers in Munich. Before Worer left, Mitchell said, “I’ve thought about you over the years.” Wondered if the tools helped if teaching you made any difference. You saved my life, Wernner replied. “Not by feeding me or giving me a bed, though that mattered, but by teaching me that I could build. That destruction isn’t permanent.

That craft continues even when everything else is lost.” Mitchell gripped his shoulder the way he had in Camp McCain 20 years earlier. That’s what I hoped. Go keep building. Wernern Mueller died in 1998 at age 68. His construction company had become one of Munich’s most respected firms.

He had trained over 200 apprentices during his career, many of whom went on to establish their own businesses. He had built over 10,000 housing units, dozens of schools, three hospitals, and countless smaller structures that made up the physical infrastructure of rebuilt Germany. Among his possessions when he died, Mitchell’s toolbox, still functional, still used daily.

The letter Mitchell had written in 1945, now yellowed and fragile, but preserved carefully, and a journal Wormer had kept, documenting every building his company had constructed, every apprentice he had trained, every moment when he had chosen to pass craft forward the way Mitchell had passed it to him. His son named James after Mitchell inherited the construction company and the toolbox.

He continued his father’s tradition of training displaced youth, of treating craft as both practical skill and moral education. In 2015, James Muller traveled to Tennessee. Mitchell had died in 1987, but his family still lived in the same house with the same workshop. James brought his grandfather’s toolbox, showed it to Mitchell’s grandchildren, told them the story of how an American carpenter had given tools to a German prisoner, and set in motion a legacy of building that had spanned seven decades.

“Mitchell’s granddaughter, herself a carpenter, examined the toolbox with professional appreciation.” “These are beautiful,” she said. “Grandpa made good work.” “He did, James agreed. And he taught well. My father never forgot that. Never stopped trying to pass it forward. They spent the afternoon in Mitchell’s old workshop, surrounded by tools and wood shavings and the smell of varnish.

Talking about craft, about teaching, about the ways that skills connect people across time and nationality and the artificial divisions that war creates. The story of Warner Mueller and James Mitchell became part of the historical record. Researchers studying post-war reconstruction cite it as an example of how individual acts of teaching and generosity contributed to Germany s recovery.

Military historians reference it when discussing the long-term impacts of humane P treatment. But the deeper meaning isn’t in academic analysis. It’s in the 10,000 housing units built with Mitchell’s tools, in the 200 apprentices trained, in the ongoing work of James Mueller and his children, continuing the tradition of building and teaching.

It is in the simple fact that a 15-year-old boy who had slept in a bed in 2 years was given not just a bed but a future. Was taught not just to survive but to create. was shown that enemies could become teachers. That craft transcended nationality, that the opposite of destruction was the patient, skilled work of building something new. The barracks at Camp McCain are gone.

The bed Wernern slept in no longer exists. But the toolbox survives, functional after 70 years, still building, still teaching, still proving that the small acts of individual humans can echo across decades. Wernern Mueller arrived in Mississippi as a traumatized war orphan who hadn’t slept in a bed in two years.

He left as a carpenter with skills and tools and the understanding that he could build something from the ruins of everything he had lost. That transformation from destroyed child to skilled craftsman happened because one American sergeant saw an enemy kid and thought, “You ll sleep in a bed tonight.

” Because one American corporal saw a talented student and gave him professional tools. Because a system designed for punishment, chose instead occasionally to educate. The war took Werner’s family, his home, his childhood, 2 years of sleeping in beds. The Americans gave him back one of those things literally, and the others metaphorically.

Not the specific losses, but the possibility of building new versions, new futures, new meanings from the rubble of what had been destroyed. Sometimes the most powerful thing you can give someone is in material wealth or complete restoration of what was lost. Sometimes it’s just a bed, some tools, and the patient teaching that says you can build from here. You have skills. You have worth.

You have a future. Wernern built that future and in building it proved that Mitchell’s gift had been more than tools. It had been faith faith that a traumatized child could become a skilled craftsman, that an enemy could become a student, that the work of rebuilding was possible, even when everything seemed permanently broken.

A bed in Barrack 7 was just a bed. But to a boy who hadn’t slept in one for 2 years, it was the first evidence that normal life life with comfort, security, dignity still existed and could be reclaimed. And that evidence, that small restoration of basic human comfort, became the foundation for everything were built afterward.

One building at a time, one apprentice at a time, one tool passed forward at a time. The way Mitchell had taught him, the way his father had taught him before the war, destroyed everything. The way craft survives across generations, nations, and even the catastrophes that try to erase