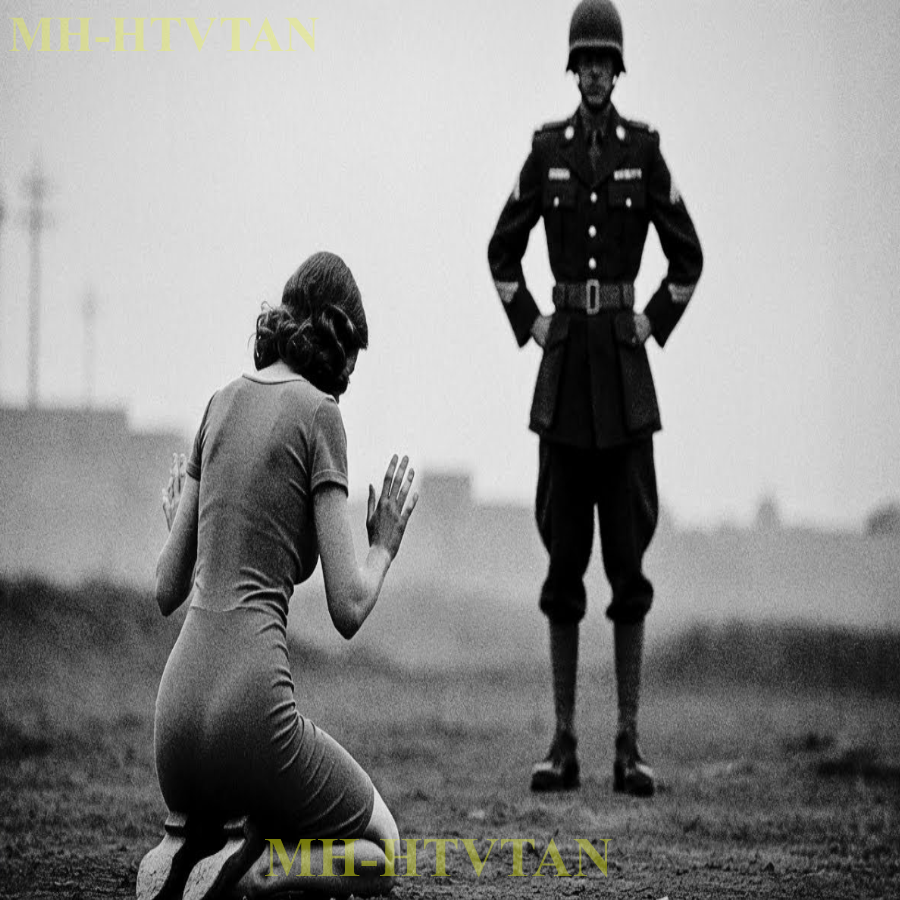

June 10th, 1945. A cold, gray morning over a barbed wire camp outside Castle, Germany. The air smelled of thin soup, wet canvas, and diesel, while boots scraped in the mud that had seen too many marches. On one side of the wire, a young German woman prisoner clutched a metal cup, sure the enemy would spit on her, or worse.

Across from her, an American soldier poured coffee and tried not to shiver in the wind. She opened her mouth to curse the man she had been trained to hate, but instead she heard herself say, “I was told to hate you.” What he answered next would stay with her for the rest of her life. This was not a story from a poster or a speech.

It was real life, and it broke everything they thought they knew about war and enemies. The war was over, but it did not feel that way to Leisel.

On 10th June, 1945, she stood in a muddy field outside Castle with hundreds of other prisoners. The sky was low and gray. The air smelled of wet earth, sweat, and the sharp bite of diesel from idling American trucks. Her boots were soaked through. Her hands shook from cold and from something that was not quite fear and not quite exhaustion, but a mix of both.

Only weeks earlier, she had worn a headset in a signals unit taking messages for an army that no longer existed. Now her gray uniform blouse was torn. The eagle on her sleeve had been ripped away by an American sergeant who spoke no German, but made his meaning clear. The symbol was gone. The power behind it was gone. She was no one’s soldier now, only a prisoner.

Castle had already fallen long before her capture. The city behind her was in ruins. More than 80% of its center had been destroyed by bombing. Whole streets were just blackened stone and twisted iron. When she closed her eyes, she could still see the red glow of burning houses and taste the grit of dust on her tongue. She had been told many stories about Americans.

Officers and party officials had warned them that capture meant shame and pain. Women, they said, would be dragged away, beaten, used. Prisoners would be starved, shot for sport, or sent to slave labor until they dropped. Surrender, they were told, was worse than death. Now she watched the men with the white stars on their helmets move among the line of prisoners.

They did not point rifles at heads for fun. They did not shout insults in broken German. One young American with a tired face and a week’s worth of stubble walked down the row with a water can. He paused at each person and filled dented cups as best he could. Drink slowly, he said in careful German when he reached her. His accent was rough, but his voice was calm. Leisel took the cup.

The water was warm and tasted of metal, but it was water. Her throat achd as it went down. She waited for the blow that never came. Later, she would think this was the first. By June 1945, more than 3 million German soldiers were in American hands in Europe.

They were counted, sorted, and guarded in hundreds of temporary camps. The system was huge, almost industrial, but inside it was single faces and small human acts like this one cup of water. One former prisoner later wrote in her diary, “We expected to be shot or cursed at once.” Instead, the first American I met said, “Are you hurt?” and tried to make me understand with his hands.

Leisel did not write that line, but it could have been hers. The column began to move. Boots sucked at the mud. Chains on the trucks clinkedked softly. Somewhere a man coughed again and again. A dry, painful sound that did not stop. An American jeep rolled slowly beside them, the engine low and steady. A guard sat in the back with his rifle across his knees, watching but not aiming. Leisel walked with her eyes on the ground.

Now and then she glanced up at the men in front of her. Some still wore pieces of uniform, others had civilian coats over army trousers. The war had mixed everything. Ranks did not matter much here. No one saluted. She tried to remember the words from the radio, from speeches in the town square. The enemy is brutal. The enemy will destroy us.

Better to fight to the last bullet. Those sentences now sounded thin in her mind, like posters left out in the rain. As they neared the camp, she saw the wire first. It rose in three tall lines shining wet with wooden posts like bare trees. Watchtowers stood at the corners, dark shapes against the gray sky.

She braced herself. This, she thought, is where the real horror begins. But even here, things did not look quite like the stories. Near the gate, a painted sign showed a red cross on a white field. There were tents marked for the sick. American medics moved among a small group of stumbling prisoners, checking bandages and taking temperatures with quick practiced hands.

She smelled disinfectant under the odor of sweat and damp boots. A cler at a rough wooden table took names and birth dates. Leisel spoke hers in a low voice, expecting a slap if she was too slow. The cler only nodded and wrote it down. To him she was another line in a list that already held thousands.

“This wasn’t propaganda,” she would think later. “This was reality, and it did not match anything we had been told.” When she stepped through the gate, and the wire closed behind her with a dull metallic rattle, she did not know that the greatest shock was still to come. The real test would not be the fences or the hunger, but the moment when the enemy spoke to her as if she were simply a person.

That moment was waiting for her on the other side of the compound. Inside the wire, life was strange and strict, but not what Leisel had feared. The compound near castle covered several fields. Rows of army tents and a few long wooden huts stood in lines with paths of crushed stone between them. The gravel crunched under boots all day. A generator hummed somewhere, a steady low sound that never quite stopped. The first thing the Americans did was count them.

They stood in rows while a sergeant walked along tapping his clipboard. Each group had a number. Each tent had a number. One officer explained in careful German that there were more than 4,000 prisoners in this camp and only about 150 guards. Order, he seemed to say, was not cruelty.

It was how everyone would stay alive. Early the next morning, a whistle blew in the cold light. The air cut like a knife. Breath rose in white clouds. Leisel pulled her thin blanket tighter around her shoulders as she stepped out of the tent. The ground was still wet. The mud now hard and stiff like rough leather after a night of wind. They lined up for food.

The smell of cooking drifted across the camp. Cabbage, some kind of meat and coffee. It was not rich food. The soup was watery and the bread was coarse and dry, but it was more than many had eaten in days at the front. Later, she heard a rumor from a Red Cross worker. By summer 1945, Americanrun camps tried to give prisoners at least 2,000 calories a day as the Geneva rules demanded, even when supplies were tight.

One older man in her tent, a former teacher from Bremen, shook his head over his tin plate. In the papers, he said quietly, “They told us the Americans would let us starve. Today I had more to eat than in the last week of the war.” His name was Otto, and his voice was tired rather than grateful. The paradox sat heavy between his words.

The enemy was feeding him better than his own army had at the end. Leisel felt it, too. Everywhere she looked, she saw contrasts. Outside the wire, castle lay in ruins with blocks where 90 out of 100 houses were gone. Inside the wire there were straight rows rations stacked in crates, medical stations with clean bandages.

She did not confuse this with kindness. It felt more like a machine working as planned, but it was still not the chaos and cruelty she had been warned of. She was sent with a group to a medical check. An American doctor, gay-haired and calm, moved from one prisoner to the next. A German-speaking medic translated, “They checked weight, listened to lungs, inspected old wounds.

The smell of carbolic soap and alcohol was sharp, almost painful in her nose. When the doctor reached her, he pointed at a thin scar along her arm.” “Bullet?” he asked. “Shrapnel,” she answered. He nodded and wrote a note. Then he said something to the medic who turned to her. “If you get fever, you come back.” The medic translated. We don’t need sickness here.

It was a practical reason, but the effect was the same. The enemy was telling her to take care of herself, not to die. Later, sitting on her bunk of rough boards with straw mattress, Leisel ran her fingers over the small vaccination mark they had given her. The skin around it was sore and hot. The idea that American hands had done this to stop disease, not to cause harm, felt upside down. This wasn’t propaganda, she thought slowly. This was reality.

At night, the camp was full of sounds. Men coughed, talked in low voices, sometimes cried out in their sleep. The wind pulled at the tent canvas, making it snap and sigh. Now and then a guard’s footsteps passed outside, steady on the stones. Flood lights washed the wire in pale light, turning raindrops into a thin silver curtain.

One former prisoner from another camp later wrote, “We were enemies in name, but they counted our rations and checked our fevers as if we were their own. It confused us more than any leaflet ever did. His words could have been spoken here.” Confusion spread like a quiet fog through the rows of prisoners.

Leisel did not stop distrusting the Americans. She remembered the bombs. She remembered the dead. But the picture in her head grew more complex. The faces on the other side of the wire were no longer only the ones from posters and speeches. They were tired boys with chapped hands, medics with lined faces, clerks who wrote too slowly when their fingers were cold.

Days settled into a pattern, roll call, food, work details, checks, long hours of waiting. The real battle now was not with weapons, but with thoughts. What do you do when the enemy does not act like an enemy? The answer began to form one afternoon when an American soldier stopped near her work detail and instead of shouting asked her a simple question.

It was in that brief awkward conversation that she finally said the words that had been burning inside her. I was told to hate you. The talk began with a splintered board and a clumsy knot. It was late afternoon. The sun hung low, throwing long shadows across the compound. The air was cool with the dry smell of dust and old wood.

Leisel stood near the inner fence with a small work party trying to repair a broken section of railing. Her fingers were numb. The rough rope burned her skin as she pulled it tight. An American soldier stepped closer. He was not much older than she was, maybe 23. His helmet sat back on his head, showing light brown hair, damp with sweat. A patch on his sleeve read Miller.

His rifle hung from his shoulder, pointing at the ground, not at them. Here, he said in simple German, “You do it like this.” He took the rope from her hands and showed her how to loop and pull so the knot would hold. His fingers moved quickly, like someone used to tying things down on trucks or farm wagons.

When he finished, he stepped back and let her try. She copied his movements. The rope creaked as it tightened. “Good,” he said. better than me. His German was slow but clear. He smiled a little, then looked almost shy, as if he had done something wrong by speaking kindly. For a moment they stood there in silence, with the fence between them and the low murmur of the camp behind.

Somewhere metal clanged on metal. A truck started with a coughing roar. The smells of the evening meal drifted across. boiled potatoes, coffee, and the faint bitter taste of burned fat. Leisel felt anger rise in her chest, unexpected and hot. She thought of her bombed street, of bodies under stone, of knights in the cellar, while the house shook.

Here stood one of the men from the planes and the guns, teaching her how to tie a knot. She heard herself speak before she had fully chosen the words. “I was told to hate you,” she said. Her voice came out flat, almost calm, but her heart was beating hard. The soldier’s head jerked slightly. His eyes met hers. For a second, something like fear passed over his face, as if he thought this might be a trap. Then he nodded.

We were told to hate you, too, he answered slowly. “All of you, all Germans.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out a pack of cigarettes. He hesitated, then held one out to her through the space in the boards. It was a simple American brand, the paper a little crumpled. The offer itself was against every picture she had ever been given of the enemy.

By summer 1945, more than 2 million German prisoners were in American hands in Europe. Training films and briefings had told the guards that these men and women came from a nation of fanatics. In turn, German propaganda had shown Americans as rich, cruel, and hungry for revenge. Now, at this broken fence, those two images stood face to face and did not match. Leisel did not take the cigarette. She kept her hands at her sides.

On the radio, she said, “They told us you would shoot prisoners, that you would do uh other things to women.” Her cheeks burned as she spoke. She did not look away. Miller shifted his weight. In the news reels, he replied. They showed us you bombing cities, marching children in uniforms. They said all of you believed in it.

They said you would fight to the last boy. He looked at her again, taking in her hollow cheeks, her thin coat. You don’t look like those films, he said. You look like the girls in my town when the harvest failed. A former American guard later wrote in a letter home. We had been trained to expect hard, cruel faces. Instead, we got tired kids and old men who shook when you raised your voice.

It was hard to keep thinking of them as monsters. His words could have been written about this moment. Leisel’s anger wavered, turned into something more like confusion. “You dropped bombs on us,” she said quietly. “Yes,” Miller answered. “We did. He did not defend it. He did not say it was necessary or deserved. His voice was flat, too, carrying its own weight.

For a while they just stood, each on their own side of the boards. The sky above the wire was turning orange at the edges. In the distance a whistle blew for the evening roll call. This wasn’t propaganda, Leisel thought, though she did not speak it. This was reality, and reality was harder to judge. around them.

Talk grew louder as prisoners lined up, boots scraping on gravel. The rope she had tied held firm when the wind came up, humming slightly against the wood. Miller adjusted the strap of his rifle. I don’t know what to think about all of it, he said at last. I just know I don’t hate you not standing here. It was a simple sentence, but it shocked her more than shouting would have.

Hate, she had been taught, was solid. Now it sounded like something that could crack. Their brief exchange ended when another guard called Miller away. He gave her a small nod and walked off, his boots clicking on the stones. Leisel watched him go, the words, “I was told to hate you.” Still hanging in the air between them. The knot in the fence stayed tight. The knot in her thoughts tightened, too.

If the enemy did not fit the old picture, what did that make her? Who had believed it? The question did not leave her, and it only grew sharper when new reports began to reach the camp. Numbers of dead, news of trials and stories that forced every prisoner to face the gray space between guilt and innocence.

After that short talk at the fence, nothing around Lizel changed, but everything inside her felt different. Days grew warmer. Dust rose from the paths with every step, dry and bitter in the nose. At night, the tents were hot and close, thick with the smell of sweat and damp straw.

Men and women lay awake, turning on hardboards, their thoughts noisier than the camp itself. News began to seep in. At first, it came as rumors. Someone said they had heard an American officer talking about camps in the east. Someone else said whole towns had seen films of dead bodies. No one wanted to believe it. They spoke in half sentences, then fell silent.

One morning, a group of prisoners was called to the edge of the compound. Leisel went with them. An American officer stood by the back of a truck. He held a thin stack of papers in one hand. His face was tight, as if he had not slept. A German interpreter spoke. “They want us to see what their soldiers found,” he said.

“In the camps, the officer handed out photographs, black and white images on cheap paper. The smell of ink and fresh print mixed with the usual diesel and sweat. Leisel took one with careful fingers. At first her mind would not accept what she saw. Rows of bodies thin as sticks piled like firewood. A striped sleeve over a bone arm.

A woman’s face with eyes that were open but saw nothing. Behind them buildings with watchtowers and wire not so different from the fence around her. Now these are lies. Someone beside her muttered, his voice shook. They are made to trick us. But the officer spoke again, his words slow. He said that more than 10,000 prisoners had been found dead in one camp alone when American troops arrived.

He said that across Europe, an estimated 6 million Jews had been murdered along with millions of others. Prisoners of war, Roma, disabled people, opponents of the regime. The interpreter repeated the numbers in German. They hung heavy in the air. Later, a former prisoner from another camp wrote, “We stared at the photos and wanted to say they were fakes, but the details were too sharp. You could see dirt under fingernails, tears in clothing. No one would invent that.

” His words matched what Leisel felt. A cold, creeping sense that the ground under her thoughts was breaking. Leisel remembered sitting in her signals room, headphones tight on her ears, passing messages along. She had not seen camps. She had not shot anyone. Yet she had worn the uniform, said the slogans, laughed at the wrong jokes.

She had listened when the radio called for faith and never asked where that path led. Inside the tent that night, she lay awake. Men whispered in the dark. Some said the Americans were lying. Others said they had heard things before, but had not wanted to know. A few wept quietly. Anger and shame twisted together. One older sergeant, who often sat alone, spoke at last.

“I fought in Poland,” he said into the darkness. “We cleared villages. They told us it was for security. I saw things I did not tell even my wife. I thought if I did not speak, maybe it was not real.” He let out a long breath. Now they show us the pictures. It was real. No one answered him. The paradox pressed on all of them. They were prisoners of the side that had bombed their cities.

Yet it was that same side now feeding them and forcing them to look at the crimes of their own leaders. They were both damaged and in some way responsible. Outside the war moved on without them. By late 1945, trials began in places like Nuremberg. Leisel heard numbers in fragments. 22 top leaders in the first trial. Millions killed in bombing and battle.

60 million dead worldwide, one American chaplain said quietly one day, his voice tired as he spoke to a small group at the edge of the camp. God will judge, the chaplain said. But so must men. Still, even in judgment there can be mercy. His German was rough, but the word mercy was clear. Leisel did not know if mercy was possible for herself, for anyone.

She thought of Miller at the fence, saying he did not hate her. She thought of the photos in her hands, the stiff, thin bodies. She thought of the teacher Otto, who had once marched his students to party rallies, now staring at his tin cup as if it held all his mistakes. This is the gray place, she realized.

Not guilt or innocence, but something in between. In that gray place, the old simple picture of the enemy could not survive. To move at all, she would have to decide what to do with that broken image. Cling to it or let it go. The choice became real on the day an object passed from one side of the fence to the other, small enough to fit in a pocket heavy enough to change how she carried the past. The days after the photographs felt heavier.

Work, roll calls, and meal times were the same, but Leisel’s thoughts were not. The dust still rose from the paths. The same generator still hummed. The smell of boiled potatoes and thin coffee still drifted from the field kitchen. Yet now, when she lay down at night, she saw two sets of images, the bodies in the pictures, and Miller’s face at the fence when he said he did not hate her.

One late afternoon, she was again sent to repair the inner rail. The wood was dry and splintered under her hands. The air was warm and full of tiny flies. Somewhere nearby, men were stacking supply crates. The thud of wood on wood came in a slow rhythm. Miller walked up, rifle on his shoulder.

“You saw the photos?” he asked in his rough German. Leisel nodded. Her throat felt tight. “Yes,” she said. Did you? He looked away for a moment. They made us watch a film, he answered. Bergenbellson, piles of dead men with no strength left. I thought I had seen war in Normandy in the Ardens, but this he shook his head. I did not know it could go that far. He did not shout.

He did not accuse her. His voice was low, carrying shame and anger of his own. An American infantryman later wrote home. We thought we knew why we were fighting. Then they marched us through a camp. After that, the war became something else. Miller could have written the same line. They stood in silence.

Beyond the fence, a truck’s gears grounded as it changed speed. Someone laughed harshly near the cookhouse. The sky above the wire was a clear pale blue that did not match the weight in their chests. Miller reached into his breast pocket. “I want to show you something,” he said.

He pulled out a small folded card, edges worn soft with time. On one side was a cartoon drawing, a German soldier with sharp teeth, tiny eyes, and a cruel smile holding a burning torch. The words beneath in English named the enemy. He tapped the picture. They gave us this in training back in 43.

He explained, “Said this is what you are, that you only understand force, that you enjoy cruelty.” He gave a short, humorless laugh. “I kept it. I thought it helped me stay hard. Now he pushed the card through a gap in the boards. I don’t want it anymore,” he said. “You can see it or burn it or throw it away, but I can’t carry it after this camp. It lies to me every time I look at it.

” Leisel took the card carefully. The paper felt thin and slightly greasy from years in a pocket. The cartoon eyes stared up at her, empty and strange. She did not see herself in it at all. Slowly, she reached into her own coat. She pulled out a small metal badge she had hidden when they first took her uniform.

It showed an eagle with folded wings, clutching a crooked cross. Once it had filled her with pride when she polished it. Now it seemed heavier than its size. They gave me this when I joined the women’s signals, she said. They said it meant honor and duty. I wore it and did not ask what else it stood for. She looked at the badge, then at the pictures in her memory.

I don’t want it either, she said plainly. She held it out through the boards. Miller hesitated, then took it in his palm. For a moment, the symbol of her old belief sat in the hand of the man she had once been ordered to hate. “This is also a lie,” she said. “Not the metal. The idea behind it.

” He closed his fingers around it, then opened them again. “I’ll get rid of it,” he said. Somewhere it can’t hurt anyone, even in their head. “Later,” he would drop it into a deep trash pit behind the kitchens where spoiled food and broken crates went. It would rust there, out of sight. They had traded scrap objects, but it felt like more.

She now held a picture of what his army had been told she was. He now held briefly the sign of what her leaders had promised she should be. Both chose to let those objects go. This wasn’t propaganda, Leisel thought, feeling the soft edge of the card in her hand. This was reality. Two people deciding what to keep and what to release.

They talked a little more. Miller told her he came from a small town in Iowa where his family farmed corn and hogs. He said that out of 16 million Americans who served in uniform during the war, his little town had sent almost 200 men. 10 did not come back. He named a brother, a neighbor, a school friend.

Leisel spoke of her village school, of her brother missing on the eastern front, of rallies in the town square, where flags had looked bright and clean against the old stone houses. The paradox was clear. Two young people from villages raised on different flags and different fears, now learning each other’s stories through a fence meant to keep them apart. A guard’s shout ended their talk.

Work time was over. That night in her tent, Leisel slid the cartoon card under her straw mattress. She did not yet burn it or throw it away. She kept it as a reminder of how easy it was to draw monsters instead of people. She did not know that this small exchange at the fence would stay in her memory long after the wire was taken down, shaping how she spoke of the war to those who had never seen a camp at all.

The camp did not last forever. By the spring of 1946, the fences were still there, but the crowd inside had grown thinner. Transport lists were read out more often. Trucks came and went in clouds of dust, carrying men and women back to cities that were now broken sketches of their old selves.

Across Europe, more than 11 million German soldiers had been prisoners of war. At some point, about 3.4 million were held by the Americans. By 1948, almost all of them had been sent home. Leisel became one of those numbers on a list. The morning her name was called, the sky was clear and sharp. The air smelled of wet grass and cold smoke from the cook house.

She stood in line with a small bundle of clothes. Her heart beat hard, though the guard at the gate looked bored, not dangerous. Miller was there. He had lost weight. His uniform hung a little loose on his shoulders. There were lines around his eyes that had not been there the first day. She saw him at the fence.

“You’re going home,” he said in German that had grown smoother with practice. “So are you?” she asked. He nodded. “Soon,” he said. “The army says they will send us back. They talk about college money, jobs. They say 16 million of us served. Now they have to find places for us in peaceful life.” He gave a small crooked smile. “Peaceful,” he repeated, as if he still did not trust the word.

Around them, boots scraped on gravel. A truck engine coughed, then settled into a steady rumble. The metal gate clanged each time it opened and shut. The smells of the camp, sweat, smoke, boiled food, mixed with the faint scent of the fields beyond, where new grass was trying to grow.

Leisel reached into her bundle and pulled out the folded cartoon card. “I kept it,” she said. “Not because it is true, because it is not.” She showed him the picture one last time. The sharp-tothed enemy with empty eyes. The lie on paper. Sometimes in the tent, we passed it around, she said. We laughed, then we did not laugh.

It helped us remember what we had believed and how wrong it was. Miller took a slow breath. I threw away your badge, he told her. Deep pit, trash, and old cans. It felt right to put it there. He looked past the wire toward the ruined city. When I came, he said, “I thought I would teach you something about freedom, about right and wrong.” We all did. We thought we knew enough, but we did not.

We saw your cities, your dead, your camps, and also your fear. We had to learn again what our own words meant. The narrator could have spoken for many when he said this. One American sergeant later wrote, “We arrived as victors, sure of ourselves. We left asking questions about our country, their country, and what people will do when they are told to hate.

We came as conquerors. We left as students.” That line fits Miller standing by the gate with dust on his boots. A German woman prisoner years later said, “In the camp, I learned more about justice from the food line and the sick tent than from all the speeches in the square. It could have been Leisel’s voice.

” Beyond the camp, countries were changing. The United States poured money, more than $13 billion, into Europe through what they called the Marshall Plan. West Germany, the land that had once sent tanks across borders, now received grain, machines, and raw materials from its former enemies. By 1955, it even joined the NATO alliance.

The map of friend and foe had turned upside down. Leisel stepped forward. The guard checked her name off the list. The gate swung open. For the first time in a long while, there was no wire in front of her. “Will you remember this place?” she asked Miller. Yes, he said more than the battles. She thought of the card in her hand, of the photographs in her mind, of the sound of the generator at night, and the taste of thin soup on cold mornings. She thought of the simple sentence she had once spoken at the fence. “I was told to hate you,” she

said now, half to him, half to herself. “I do not anymore, but I will remember that I was told.” He nodded. “Maybe that is the lesson,” he said. to remember what we were told and then remember what we saw. The truck driver shouted, hurrying them along. Leisel climbed into the back with the others. The wooden boards were rough under her hands.

As the truck pulled away, the camp grew smaller behind her, tents, towers, and finally just a thin gray line of wire. She did not know where life would carry Miller back to Iowa, to a factory, to a college classroom. He did not know how she would rebuild her days among ruins that smelled of brick dust and new plaster.

But for both of them, the old easy story of enemies had broken. This was not propaganda. This was reality. Lived in mud, barbed wire, and quiet talks by a fence. Their brief meeting became part of something larger. nations that learned slowly and painfully that abundance could rebuild where bombs had destroyed and that former foes could stand side by side against new threats.

In the years ahead, there would be more wars, more walls, more speeches that tried to turn people into pictures. But there would also be memories like leasels and millers carried silently across oceans and decades. a reminder that even in the worst times, someone can choose to reach past the wire and see a human face.

In the decades after the war, Leisel lived in a rebuilt German town where the smell of fresh bread and factory smoke replaced the stench of rubble. She married, worked, raised children. On a high shelf in a small wooden box, she kept the cartoon card from the camp. Sometimes a grandchild would find it and ask, “Who is this supposed to be?” Then she would say, “That is what we were told an enemy looks like, but it is not what they really look like.” Cross the ocean.

Miller grew old, too. One of the millions of veterans who rarely spoke about the worst days. Yet when he did, he sometimes mentioned a German woman at a fence who said, “I was told to hate you.” In the end, the strongest weapon either of them carried was not a gun or a flag, but the simple choice to refuse that hate.