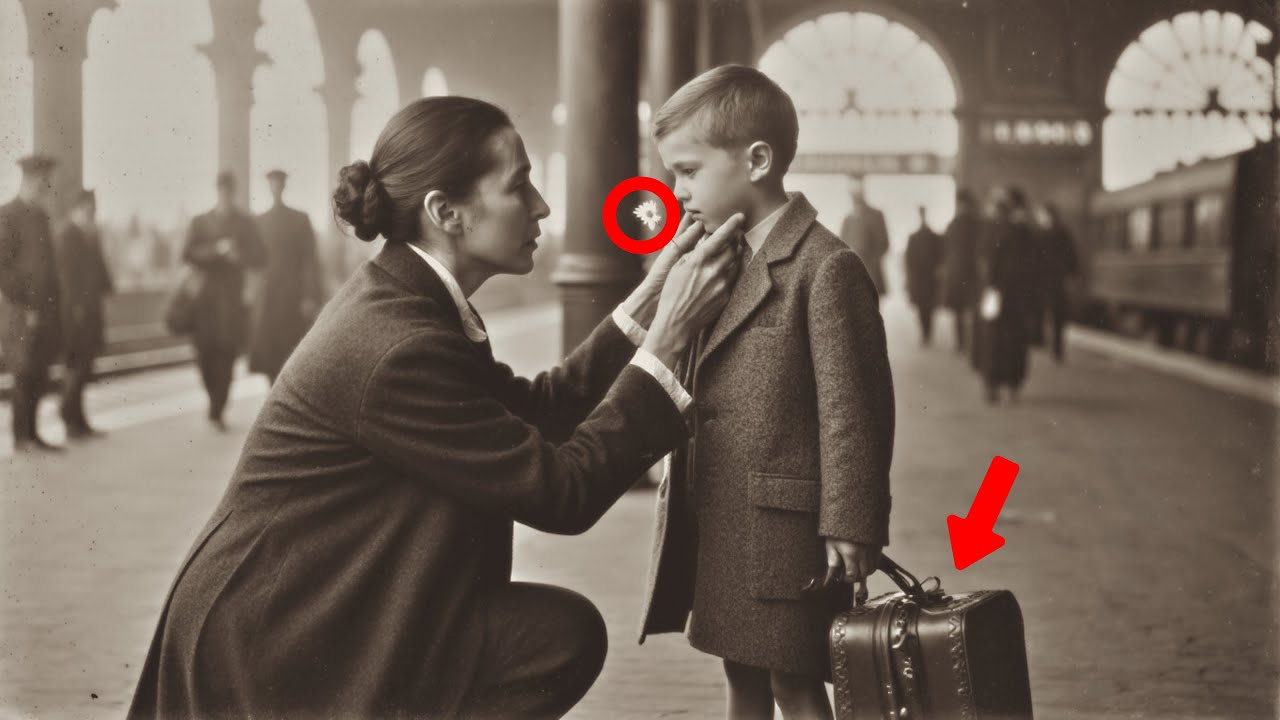

Have you ever wondered what it would feel like to say goodbye to someone you love, not realizing it would be the last time you ever saw them? In 1913, at Union Station in St. Louis, a widowed mother named Margaret O’Donnell held her son’s face in her trembling hands.

She believed she was sending him away for a better life. But what happened on that platform changed everything. Decades later, a simple photograph tucked inside a Bible would reveal the heartbreaking truth. And tonight you will hear this dramatized story inspired by real history with every detail that time almost erased.

They remind us of the sacrifices our ancestors made and the hidden costs of survival. Your voice helps keep these memories alive. March 14th, 1913, Union Station, St. Louis.

A mother held her son’s face in her hands, not knowing she was touching him for the last time. Margaret O’Donnell, 33 years old, widow, mother of three, was about to make a decision that would haunt two lives forever. In exactly 47 seconds, according to the photographer who captured the moment, she would let go of 11-year-old James and watch him board a train to Chicago. Neither of them knew that fate had already written a different ending to their story.

If you stay until the end of this story, you’ll discover why Margaret kept returning to this exact spot every March 14th until the day she died, and why her son James carried a piece of homemade soap in his pocket for the next 68 years. This is the story of a mother who sacrificed everything for a future that would never come and a son who learned to read just to find his way back home only to discover that some journeys can never be completed.

The photograph was discovered in 1967 tucked inside a Bible at the St. Patrick’s Church rectory in Kerry Patch, the Irish neighborhood where the O’Donnell’s once lived. But look closely at Margaret’s hands in that image. See how they tremble slightly, blurred despite the photographers’s steady tripod.

Those hands had developed early arthritis from washing clothes in freezing water every winter morning since her husband died. Those hands that could barely close into fists anymore were holding their most precious thing one last time. Station records from that day, preserved in the Missouri Historical Society archives, show that the Chicago and Alton Railroad departure was scheduled for 10:47 a.m.

Ticket number 1247 was purchased a week prior after Margaret O’Donnell sold her wedding ring to Goldstein’s Pawn Shop on North Grand Avenue. The receipt found decades later among church donation records showed she received $12.70, just enough for one child’s passage to Chicago. But Margaret was keeping a terrible secret from her son. A secret that would only be revealed when Mary Flanigan, their neighbor, gave her testimony to a local historian in 1967.

Margaret hadn’t eaten a full meal in 3 weeks. Every morning she gave her portion to the children, claiming she’d already eaten while preparing breakfast. The morning of March 14th, their last breakfast together was hot water with sugar. Nothing else. James didn’t know his mother had already chosen which child would have the best chance of survival.

This is James O’Donnell, 11 years old, oldest of three children. That small suitcase he’s carrying, almost bigger than his thin frame, contained everything he owned. Two shirts, one pair of pants, a piece of homemade soap that smelled like his mother, and hidden in the lining, a harmonica. Margaret had saved pennies for 6 months to buy that harmonica from Woolworth’s five and dime.

She knew James loved music, would hum Irish songs while working. What she didn’t know was that James had wet his bed the night before. Too ashamed to tell her, too scared about leaving to sleep properly. Notice the scar on his chin, barely visible in the photograph, but mentioned in his work registration papers years later.

That scar came from his father’s fist 2 years earlier, the night before Patrick O’Donnell died in a bar fight on the docks. James had tried to stop his drunk father from hitting Margaret. The boy was 9 years old. The scar would follow him forever, but on this morning, Margaret kept touching it gently, as if she could heal old wounds with goodbye kisses.

The conductor, Thomas Mitchell, wrote in his personal diary, discovered in 1962, about that particular morning run. He remembered the Irish woman who couldn’t read the signs, who kept asking other passengers to confirm this was the Chicago train. He remembered how she counted the money three times before handing it over.

He remembered the boy with the stutter who couldn’t properly say goodbye, whose words kept catching in his throat like stones because that’s what no one talks about in the official records. James had developed a nervous stutter after his father died. It got worse when he was scared and on that platform trying to tell his mother he loved her, trying to promise he’d write even though he could barely form letters, trying to be brave like she’d asked him to be. The words wouldn’t come.

They just stood there, mother and son, understanding everything through silence. What James didn’t know was that his 5-year-old brother, Timothy, was angry at him. The night before, James had eaten an apple that Margaret had saved for the youngest child. She had screamed at James, called himself, said he was just like his father.

Those words hung between them now, unforgivable and unforgiven. Margaret would replay that moment every night for the rest of her life. Her last harsh words to her oldest son were about an apple. The photographer, an Italian immigrant named Juspe Romano, later testified that he’d never seen a mother hold a child’s face that way.

Like she was trying to memorize every detail, like she was storing up enough love to last a lifetime. He gave them the photograph for free. Couldn’t bring himself to charge for documenting that kind of goodbye. But even he didn’t know the full truth. To understand what happened next, we need to go back 6 months to September 1912.

Carrie Patch St. Louis was a neighborhood where hope and despair lived in the same tenement buildings. The Irish who’d fled the potato famine had built a community here, but by 1912, it was a community under siege. The men were dying in industrial accidents or drinking themselves to death.

The women were raising children alone, washing clothes for pennies, watching their babies die of diseases that money could cure. Margaret O’Donnell’s life changed the day she received a letter she couldn’t read. Mrs. Benadeti, the Italian widow next door, who’d secretly been teaching James to make bread, read it aloud.

Margaret’s brother-in-law in Chicago, Thomas O’Donnell, was offering to take James as an apprentice in his furniture workshop. The boy would learn a trade, attend school, have three meals a day. All Margaret had to do was put him on a train.

The Saint Vincent Depal Society records show that the O’Donnell family had been receiving charity assistance since Patrick’s death in 1911. 2 lb of flour weekly, occasional vegetables cast off clothing. But by winter of 1912, even that wasn’t enough. Margaret was washing clothes for five different families. her hands bleeding from the lie soap, working 18 hours a day. Still, she couldn’t feed three children.

James had been helping however he could without telling his mother he’d been watching the watch maker on Grand Avenue, studying how the tiny gears fit together through the shop window. When Mr. Hoffman’s pocket watch broke, James fixed it with a hairpin and a needle. Word spread through the neighborhood.

The Irish boy had clever fingers, but clever fingers couldn’t fill empty stomachs. The decision of which child to send away broke Margaret’s mind a little. Timothy was too young at 5, would die without his mother. Catherine, at seven, was sickly, needed constant care. James was the strongest, the smartest, the one with the best chance. But he was also the one who looked most like his father.

The one who reminded her of everything she’d lost and everything she’d endured. Some nights when whiskey blurred the edges of hunger, she hated him for that resemblance. Other nights she held him so tight he could barely breathe. The neighborhood knew something the odds didn’t. The week before James left, Margaret had been seen at Dr. Morrison’s clinic.

The charitable doctor who treated the poor had given her news she never shared with her children. The persistent cough that kept her awake, the blood on her handkerchiefs, the weight loss she blamed on giving her food to the children. The early stages were already there. She might have 2 years, maybe three if she was lucky. Sending James away wasn’t just about his future. It was about ensuring at least one child would survive what was coming.

James knew none of this, but he knew other things. He knew his mother had started drinking his father’s hidden whiskey bottle, the one she’d sworn never to touch. He knew she cried when she thought he was asleep. He knew that despite the promise of Chicago, part of him was relieved to be leaving. The guilt of that relief would follow him forever.

What kind of son feels grateful to escape his mother’s suffering? The train ticket to Chicago came with conditions nobody talked about. Thomas O’Donnell’s letter preserved in church records mentioned that James would work without wages for the first year, room and board in exchange for labor. It was legal, commonplace, and exactly what happened to thousands of immigrant children. They called it opportunity.

Today, we’d call it something else. March 13th, 1913, the night before departure. The St. Lewis Post Dispatch would later report this as one of the coldest March nights on record. In the O’Donnell’s tenement apartment, the four of them huddled together for warmth.

Margaret had saved one last surprise, a luxury beyond imagination. Four apples from the market, one for each of them, a farewell feast. But Timothy was sick with hunger, crying for more. James, trying to be the man of the house, gave Timothy his apple. Then when everyone was asleep, his stomach screaming, James ate the apple Margaret had saved for Catherine’s breakfast. His mother caught him, apple juice still on his chin. The slap came hard and fast.

The words came harder. Selfish like your father taking food from your sister’s mouth. Is this who you are? James ran to the corner of the room, the one where his father used to make him stand as punishment. Margaret didn’t call him back. She sat at the table, head in and her hands, shoulders shaking. Neither of them slept that night. Neither of them apologized.

The apple core stayed on the table between them like an accusation until morning. Mrs. Benadeti would later tell investigators that she heard Margaret praying in Gaelic that night. The old prayers her own mother had taught her. Prayers for forgiveness, for strength, for time she didn’t have.

But most of all, prayers that James would forget this night. Forget her cruelty. Remember only the good moments that were getting harder to find. March 14th, 1913. 64 a.m. Margaret woke James with a gentle shake, so different from the anger of the night before.

She’d already prepared his traveling clothes, the ones she’d mended so many times, the original fabric was barely there. In his small suitcase, between the two shirts and spare pants, she’d hidden something James wouldn’t discover until that night. A note she’d asked Mrs. Benadeti to write for her. Five words that would haunt him forever. Forgive me. Love you always.

The walk to Union Station took 47 minutes, according to the police report filed later that year, when Margaret first reported James missing. She’d measured the distance, timed it, as if knowing these details could somehow bring him back. They passed the butcher shop where James had stolen a sausage the previous winter, desperate with hunger.

They passed the church where his father was buried in a popper’s grave. They passed the watchmaker shop where James had learned that broken things could sometimes be fixed. Timothy, the 5-year-old, didn’t understand what was happening. He kept asking when James would be back for supper. Catherine, seven and always sickly, understood too well.

She walked in silence, holding James’s hand so tight it hurt. At the corner of Market Street, she suddenly stopped and gave James her most precious possession, a button from their father’s coat, the only thing she had of his. James would carry that button for the rest of his life, sewn into every jacket he ever owned.

The crowds at Union Station were overwhelming. Irish families sending sons to factories. Italian families reuniting after years apart. German families heading west for farmland. Among all these dreams and desperations, the O’Donnell’s were just another poor family making an impossible choice. The ticket agent barely looked up when Margaret, unable to read, asked three times if this was the correct platform for Chicago. Then came the moment that changed everything.

Thomas O’Donnell, the uncle who was supposed to meet James in Chicago, had sent a telegram that morning. But Margaret couldn’t read it. And in the chaos of departure, no one offered to help. The telegram found years later in station records contained five words that would have changed everything. Workshop closed.

Don’t send boy. At 10:15 a.m., 32 minutes before departure, James found a penny on the platform. In his world, this was fortune beyond measure. He could buy candy or a pencil or save it for Chicago. Instead, he ran to the station’s flower seller and bought a single wilted daisy for his mother.

Margaret would press this daisy in her Bible where it would be found 54 years later, still wrapped in the tissue paper James had carefully preserved. The photographer, Josephe Romano, was setting up his camera, offering portraits for travelers. Margaret had no money for such luxury, but Romano saw something in her face. Later, he would tell his own children that he’d never seen such desperate love. He offered to take their picture for free.

Just one, a memory to hold on to. The exposure would take several seconds. They would need to be perfectly still. This is when James’ stutter became unbearable. He wanted to tell his mother so many things. That he was sorry about the apple. that he would write every week even though he could barely form letters, that he would send money as soon as he could.

That he was scared of dogs and what if Uncle Thomas had dogs? But the words wouldn’t come. They caught in his throat like the sob he was trying not to release. Margaret pulled him close, kneeling despite the pain in her arthritic knees. She held his face, that beautiful face that looked so much like the man who’d hurt her and loved her and left her alone with three children and no hope.

She whispered in Gaelic, the language of her mother, words James only half understood. Later, with the help of other Irish immigrants, he would translate these words, “You are my heart walking outside my body.” The whistle blew for the first boarding call. Families began moving toward the train. Margaret’s hands shook as she pulled out the harmonica, her last surprise.

6 months of saving pennies, of going without lunch, of mending other people’s clothes by candle light when she could barely see. James clutched it like a lifeline. This proof that his mother knew him, loved him, believed he deserved beautiful things. But then Margaret saw something that made her blood freeze.

Standing near the Chicago train was Michael Sullivan, a known labor contractor who recruited children for the coal mines. He was watching James had already marked him as a likely candidate. Strong enough to work, young enough to manipulate, poor enough to disappear without much fuss. The Chicago and Alton Railroad often had these recruiters looking for unaccompanied children whose families wouldn’t have the means to search for them. Margaret grabbed James tighter. suddenly uncertain.

The saint Vincent Depal Society would later document her visit that afternoon after James was gone, begging them to check on Thomas O’Donnell’s workshop in Chicago. But by then it was too late. The train was pulling away and James was pressing his face against the window, watching his mother grow smaller and smaller, not knowing that Michael Sullivan had already telegraphed ahead to his associates in Springfield. 10:47 a.m.

The exact moment of departure was recorded in the station log, a routine entry that would later become evidence in a desperate search. Margaret stood on the platform until the train disappeared completely until other travelers complained she was blocking their way until a station guard gently told her she needed to leave. But she didn’t leave.

She walked to a bench, the one with a clear view of arriving trains, and sat down. This would become her ritual, her religion, her reason to keep living. On the train, James clutched his harmonica and the piece of soap that smelled like home. Next to him sat a German family heading to Chicago. The parents trying to quiet a crying baby.

James, remembering how his mother used to calm Catherine, began playing a soft Irish lullabi on his harmonica. The mother smiled at him, offered him a piece of bread. It was the first kindness he’d received from a stranger, and it made him cry harder than he had at the station. The train stopped in Springfield, Illinois at 2:23 p.m. for a routine coal and water break. Passengers could stretch their legs, buy food if they had money.

James had nothing but the penny he’d found earlier, now tucked in his shoe for safekeeping. This is when Michael Sullivan’s associates made their move. They approached James with an official looking document, claimed there was a problem with his ticket that his uncle had sent word to redirect him to temporary work while the workshop was being repaired.

James, 11 years old, unable to read, terrified of authority, went with them. The German family who’d shared their bread noticed too late. The mother would later write to the St. Louis Post Dispatch about the thin Irish boy with the harmonica who disappeared in Springfield. But by then, James was already in a wagon heading to the Sangaman County coal fields, where boys his age worked 14-hour shifts for room and board, where asking about Chicago earned you a beating, where the only music was the sound of pickaxes and dying dreams. Back in St. Louis, Margaret waited at the

station until closing. She returned home to find the telegram from Thomas O’Donnell pushed under her door. Mrs. Benedetti read it to her, watched her face crumble, held her as she screamed. The workshop had closed 2 days ago. Thomas was looking for work himself. He never received James. He never even knew the boy had been sent.

What followed was 11 years of searching. The police report filed on March 16th, 1913 described James O’Donnell, 11 years old, brown hair, blue eyes, scar on chin, slight stutter, carrying a harmonica. The case was assigned to detective Patrick Murphy, who took special interest because he was Irish himself, had seen too many Irish boys disappear into America’s industrial machine.

But there were hundreds of missing children, limited resources, and no witnesses who’d seen what happened in Springfield. Margaret learned to write her son’s name just so she could make missing person posters. She paid a student 5 cents to write the rest. Missing James O’Donnell. Last seen Chicago train. Mother searching any information to Margaret O’Donnell. Carrie patch.

She posted them at every train station within a 100 miles. She wrote to every church, every charity organization, every Irish society in Illinois. The responses were always the same. No information. Many prayers. Keep faith. Meanwhile, in the coal fields of Sangaman County, James was becoming someone else.

The overseers called him Jimmy. Sometimes boy, sometimes nothing at all. He worked in the sorting rooms at first, separating coal from rock until his fingers bled. Later, when he was stronger, they sent him into the mines. The contract he couldn’t read bound him for 3 years of unpaid labor.

Other boys had been there longer, had given up hope of leaving, but James had his harmonica hidden in his mattress, and at night, very quietly, he would play his mother’s songs and remember her face. The moment that would define both their fates came on November 9th, 1919. James, now 17, had finally learned basic reading at a workers’s education meeting held secretly in a barn.

Socialist organizers were teaching minors to read so they could understand their contracts, their rights. James wrote his first letter home, addressing it simply to Margaret O’Donnell, Carrie Patch, St. Louis. He didn’t know street numbers, didn’t know if she was still alive.

didn’t know that she’d moved three times trying to afford rent, always leaving forwarding addresses with neighbors in case James returned. The letter took 8 days to reach St. Louis. It arrived at the old apartment on November 17th, 1919. The new tenant, not knowing any O’Donnell’s, marked it, returned to sender. That same morning at 6:47 a.m., Margaret O’Donnell died of pneumonia at the city hospital charity ward.

She’d been fighting the infection for 2 weeks, refusing to die, telling nurses she needed to wait for her son. Her last coherent words recorded by nurse Patricia Walsh. Tell James I waited. Tell him about the apple. Tell him I’m sorry. She died holding an envelope with $127. Every penny she’d saved for 6 years for James’s return ticket. In her other hand was the dried daisy he bought her with his found penny.

Around her neck on a string because she’d sold the chain was a locket with a photograph. Not the station photograph which she’d given to Mrs. Benadeti for safekeeping, but an earlier one. James at 9 before his father died, before the scar, before the stutter when he still smiled without reservation.

James received his returned letter on December 3rd, 1919, marked with the stamp that would haunt him forever. address deceased. He was 17 years old, free from his contract, working in a Chicago factory, sleeping in a boarding house with 12 other men. He’d saved $43 to go home for Christmas, to surprise his mother, to finally play her songs on the harmonica in person.

Instead, he sat on his narrow bed holding the unopened letter, understanding that some words arrive too late to matter. But James went to St. Louis anyway. He arrived at Union Station on December 15th, 1919, carrying the same suitcase from 6 years ago, now held together with rope. The first person he met was Patrick Murphy, not the detective who’d searched for him, but the old ticket seller who’d been working that platform since 1900.

Patrick recognized something in James’s face, the ghost of the boy with the stutter, and told him what he’d witnessed. Margaret O’Donnell coming every March 14th, sitting on the same bench, holding two apples, waiting for a boy who never came. The walk to Carrie Patch took James past the same landmarks, now changed beyond recognition. The watchmaker’s shop was closed, Mr.

Hoffman dead from the influenza. The church had a new priest who’d never heard of the O’Donnell’s. The tenement where they’d lived had been condemned, but Mrs. Benadetti was still there, older, grayer, still making bread. When she saw James at her door, she crossed herself and whispered, “Madonna, Mia, the dead walk.

” She gave him everything she’d saved, the station photograph, Margaret’s Bible with the pressed daisy, the envelope with $127, and something unexpected, a box of letters. Every week for six years, Margaret had dictated letters to James, paying Mrs. Benadetti’s daughter a penny each to write them.

Letters about Timothy growing taller, about Catherine getting stronger, about the neighborhood changing, about her dreams for his future. Letters that were never sent because there was nowhere to send them. Love floating in limbo, waiting for an address. James learned that Timothy was working at the docks. Married young to escape poverty. Catherine had joined a convent, finding in faith what she couldn’t find in family.

Neither wanted to see him. To them, he was the chosen one who’d abandoned them, who’d left them to watch their mother die slowly, calling his name. The reunion James had imagined for 6 years would never happen. Some bridges, once burned by circumstance, can’t be rebuilt by regret. At St. Patrick’s Church, Father O’Brien showed James the registry of deaths. November 17th, 1919. 6:47 a.m.

Cause pneumonia. Age 39. Buried. Calvary Cemetery. Section 15. Unmarked grave. The priest knew to the parish had never met Margaret but had heard stories. The woman who washed clothes until her hands bled. The woman who saved pennies in a jar marked James’s return. The woman who died trying to stay alive for a ghost.

James used 50 of his mother’s saved dollars to buy a headstone. The inscription was simple. Margaret O’Donnell 18801919. Mother, she waited. The rest of the money, the remaining $77, he donated to create what he called the Margaret O’Donnell Fund at St. Patrick’s specifically for widowed mothers who needed to keep their children. The fund exists to this day, having helped hundreds of families stay together.

On March 14th, 1920, exactly 7 years after their goodbye, James returned to Union Station, he brought two apples, sat on Margaret’s bench, and waited, not for anyone to arrive, but to understand what waiting felt like. An old woman selling flowers told him about the Irish lady who used to sit there, who would tell anyone who’d listen about her boy, James, how smart he was, how he could fix watches, how he played the harmonica like an angel. The woman still had one of Margaret’s missing person posters, kept it because the desperation in the

simple words touched her heart. James stayed in Saint Lewis for three more days, searching for traces of his mother’s life. He found them in unexpected places. The grosser remembered how she’d count pennies three times, apologizing. The pharmacist recalled how she’d beg for credit for Catherine’s medicine, always paying back eventually.

The priest at the poor house knew her as the woman who volunteered to wash soiled linens when she could barely stand from exhaustion, saying, “Work was prayer. Prayer was hope. Hope was all she had.” What destroyed James most was discovering that his mother had died 8 days before his letter arrived. 8 days. If he’d learned to write one week earlier, if the mail had moved faster, if God had been slightly kinder, she would have known he was alive.

She would have died knowing her waiting had purpose. Instead, she died believing he’d forgotten her, or worse, that he’d chosen not to return. The cruelty of that timing would wake James in cold sweats for the next 60 years. Before leaving St. Louis forever, James visited the pawn shop where Margaret had sold her wedding ring.

Goldstein’s son now ran it had records going back decades. $12.70 for a thin gold band. March 7th, 1913. The ring had been sold years ago, but the ledger entry remained. Margaret O’Donnell one ring claimed extreme need. paid in full, no return. James bought the ledger page for $5, framed it, kept it as evidence of a mother’s sacrifice that no photograph could capture.

The epilogue writes itself in small moments across six decades. James became a mechanic in Chicago, married a kind woman named Rose, who understood that some wounds don’t heal. They had four children, all given Irish names, all taught to play harmonica. Every March 14th until his death in 1981, James returned to Union Station with two apples.

He’d sit on the bench, now replaced many times, but always in the same spot, and tell strangers about Margaret O’Donnell, the strongest woman who ever lived, who waited for a son who couldn’t find his way home in time. The station photograph survives in the Missouri Historical Society cataloged simply as Irish immigration personal cost circa 1913.

But if you know where to look, if you understand what you’re seeing, you can observe the exact moment when love becomes loss, when hope becomes weight, when 47 seconds of holding on must last a lifetime. You can see Margaret memorizing her son’s face and James trying not to stutter. And between them, invisible but undeniable, the apple that would haunt them both forever.

James died on November 17th, 1981, exactly 62 years to the day after his mother. The nurses at Chicago Memorial said it wasn’t his cancer that chose the date. He simply decided it was time. In his pocket, they found three things. the button from his father’s coat that Catherine had given him, the returned letter he never opened, and a piece of soap worn down to almost nothing, that still somehow carried the faintest scent of home. His children donated his harmonica to the St.

Louis History Museum, where it’s displayed next to the station photograph. The placard reads, “Immigration often meant family separation.” This harmonica represents one such story. But that clinical description misses everything. The six months of Margaret’s saved pennies, the secret songs in the coal camps, the lifetime of playing Irish lullabies to remember a mother’s voice, the way music can hold what words cannot.

The last entry in James’ journal found after his death was dated March 14th, 1981. His final visit to Union Station. Went to mom’s bench today. Getting harder to walk there. Told her about the great grandchildren. About how Tommy looks just like her. About how I finally forgave myself for the apple. Forgive her, too. Though there was nothing to forgive. Love doesn’t need forgiveness.

It just needs to be remembered. Mom, if you’re listening somewhere, I remember. I never stopped remembering. Your boy came home. Just took the long way. the longest way, but I made it. I love you always. You’re Jamie. Perhaps that’s the real tragedy of Margaret and James O’Donnell.

Not that they were separated, not that they never reunited, but that they spent their lives loving each other across an impossible distance, each believing they’d failed the other. Margaret died thinking James had forgotten. James lived knowing he’d remembered too late. Between them stretched 6 years and 200 m that might as well have been eternity. But love, real love, the kind that makes a mother save pennies she doesn’t have and a son carry soap until it dissolves to nothing. That love doesn’t die with disappointment. It transforms.

It becomes the fun that helps other mothers. It becomes the bench where strangers hear about sacrifice. It becomes the harmonica in a museum that still, if you listen closely, carries the echo of Irish lullabibis and a mother’s endless hope. Every immigrant family has a Margaret, a James, a station where someone said goodbye, not knowing it was forever.

Every photograph in every archive contains a universe of waiting, of letters that arrived too late, of love that had nowhere to go but deeper into memory. This is just one story, but it’s also every story. It’s your story if you’ve ever loved someone across time and distance and terrible silence.

It’s all of our stories written in the space between holding on and letting go. In those 47 seconds when a mother memorizes her child’s face, not knowing she’s memorizing it forever. Before we close, let’s pause on what this dramatized story drawn from fragments of real immigrant lives in early 20th century America reminds us. Sometimes love is expressed not in perfect words or happy reunions, but in small sacrifices that echo across generations.

A ring sold, a piece of soap carried, a daisy pressed in a Bible. These things teach us that even when families are torn apart, love has ways of surviving, of transforming into memory, legacy, and lessons for those who come after. What about you? Have you ever thought about what a parents sacrifice might have meant for their children decades later? If you were James, what would you have wanted to tell Margaret in that final moment at the station? And if you were Margaret, how would you live with the weight of sending your child away for a chance at survival?