It was a portrait of love until you look closely at the mother’s hands. The afternoon light filtered through dusty windows of Morrison’s antique auction house in downtown Portland, casting long shadows across tables cluttered with forgotten relics.

Elizabeth Morgan moved slowly between the displays, her practiced eye scanning porcelain figurines, tarnished silverware, and stacks of yellowed photographs. At 63, she had spent four decades behind a camera, capturing weddings, graduations, and family portraits across Oregon. Now retired, she found herself drawn to these sales, searching for fragments of lives once lived.

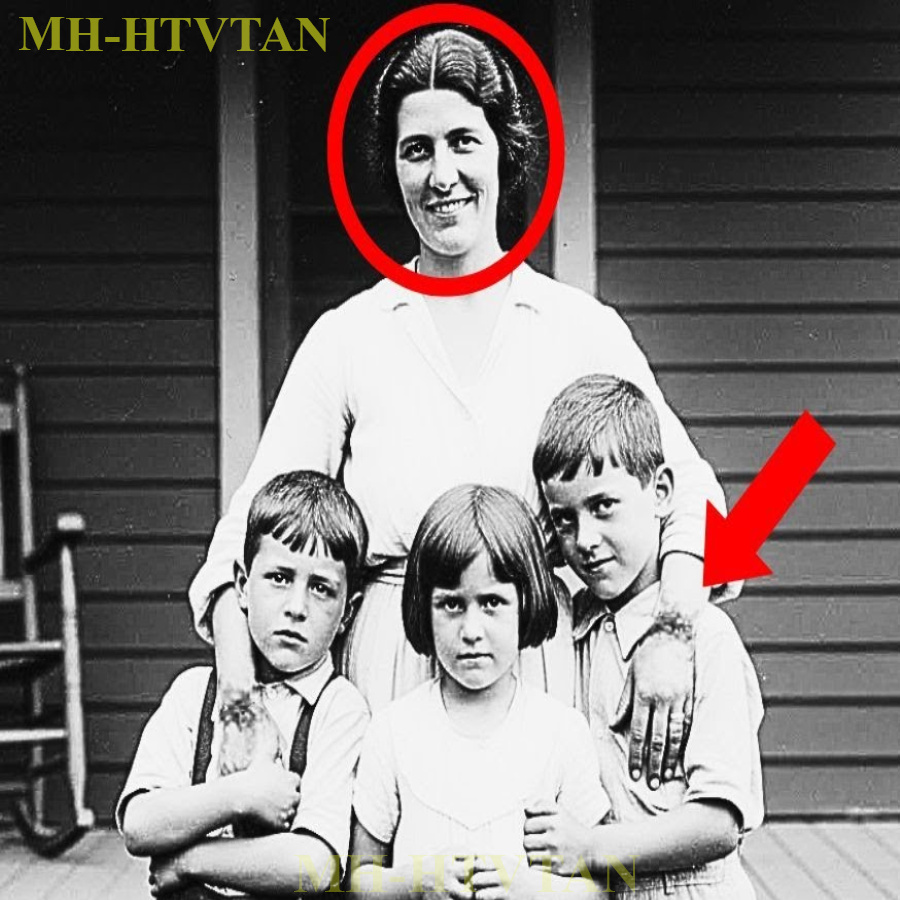

She paused at a cardboard box labeled mixed ephemera, $5. Inside lay a jumble of postcards, letters, and loose photographs. Elizabeth lifted them carefully until her fingers touched a larger print, roughly 8 by 10 in, mounted on thick cardboard. She pulled it free and held it toward the window light. The photograph showed a woman, perhaps 30 years old, standing on the porch of a modest wooden house.

Three children clustered around her, two boys and a girl, their ages ranging from about four to nine. The woman’s face was striking, high cheekbones, dark hair pulled back in the style of the 1920s, and a radiant smile that seemed to light up the entire composition. Her arms wrapped protectively around the children, pulling them close against her simple cotton dress.

Elizabeth felt something catch in her chest, that instinct she developed over thousands of sessions, the sense that a photograph held more than its surface revealed. She studied the woman’s expression more closely. The smile was genuine, reaching her eyes, crinkling the corners with authentic joy.

The children looked happy, relaxed, their small hands resting trustingly against their mother. Yet something felt wrong. Elizabeth turned the photograph over on the back written in faded pencil. Mom and us, Seattle, June 1926. Nothing more. No names, no address, no photographers mark. She flipped it back and brought it closer, squinting in the dim light.

The image quality was remarkable for its era. Sharp focus, good exposure, professional composition. But it was the woman’s hands that drew Elizabeth’s attention. The left hand rested on the older boy’s shoulder, but even in the grainy resolution, Elizabeth could see darkness circling the wrist where the sleeve pulled back slightly.

The right hand curved around the little girl’s waist, and there, barely visible, but unmistakable once noticed. The same unshadowing, the same marks. Elizabeth’s breath caught. She knew bruising when she saw it. She’d photographed enough domestic violence survivors in her later career, working with women’s shelters, documenting injuries for court cases. These weren’t shadows from poor lighting.

These were injuries deliberately hidden by long sleeves on what appeared to be a warm summer day. But the woman’s face showed no trace of suffering. Only love, only that brilliant protective smile. You buying that box, ma’am? The auctioneer’s assistant appeared beside her, clipboard in hand. Elizabeth looked up, the photograph still gripped in her fingers.

Yes, she said quietly. Yes, I am. Elizabeth drove home through the evening traffic, the photograph resting on the passenger seat beside her. She kept glancing at it at red lights, unable to shake the feeling that the woman in the picture was trying to tell her something across 31 years of silence. Her Craftsman house in the Alama neighborhood welcomed her with familiar creeks as she unlocked the door.

Without bothering to remove her coat, Elizabeth went straight to her study, a converted bedroom lined with filing cabinets and shelves holding decades of negatives and prints. She cleared space on her workt and positioned her professional magnifying lamp over the photograph. Under the bright focused light, the details emerged with painful clarity.

The marks on both wrists were definitely bruises, dark and extensive, forming rings that suggested restraint or repeated gripping. The woman’s knuckles on her right hand showed swelling, and what Elizabeth had initially taken for shadows along her forearms now revealed themselves as additional contusions poorly concealed by the fabric of her dress. Elizabeth pulled out her notebook and began documenting everything she observed.

The house behind the family appeared to be a typical Seattle working-class home from the period. Wooden siding, simple porch, no ornate details. The climbing rose bush suggested someone cared for the property. The lace curtains in the windows indicated modest domesticity, an attempt at beauty despite limited means.

The children’s clothing was clean and well-maintained, though clearly not expensive. The older boy wore knickers and a white shirt. The younger boy had on overalls. The little girl’s dress, while simple, showed careful mending at the hem. These were love children, cared for despite what appeared to be financial constraints. But it was the mother who commanded attention.

Her dress was long sleeved despite the season. June and Seattle could be warm. Her posture was upright, almost defiant, as if she were claiming this moment, insisting on this record of her love for her children. The smile never wavered, never showed cracks. But her eyes, when Elizabeth studied them under magnification, held something else.

Not sadness exactly, but determination, purpose. Elizabeth sat back and rubbed her tired eyes. The evening had deepened into night outside her window, and her stomach reminded her she’d skipped dinner. But she couldn’t stop looking at the photograph, couldn’t stop wondering about the story it concealed. She turned it over again, studying the faded pencil inscription.

Mama and us, Seattle, June 1926. The handwriting was careful, almost childlike, as if written by someone with limited education or perhaps by one of the children themselves years later, trying to preserve a memory. Seattle in 1926. Elizabeth did the math quickly. 31 years ago. If the woman was 30, then she’d be 61 now, almost Elizabeth’s own age.

Were any of those children still alive? Did they remember this day? This photograph? Their mother’s smile? Elizabeth made a decision. Tomorrow she would begin searching for answers. She had connections in Seattle, other photographers, historical societies, libraries with old city directories. Someone somewhere might remember this family, might know what happened in that house with the roses and lace curtains.

She owed it to the woman in the photograph, to those bruised hands holding her children so tenderly, to that smile that refused to break despite everything. Morning came cold and gray, typical for Portland in November. Elizabeth woke early, the photograph already occupying her thoughts before she’d fully opened her eyes.

Over coffee, she made a list of potential resources. The Seattle Public Libraryies historical archives, the Washington State Historical Society, old newspaper collections, and her colleague Thomas Chen, a retired photojournalist who had worked in Seattle during the 1940s. She called Thomas first. His voice was warm and curious when he answered.

Elizabeth, haven’t heard from you in months. What’s got you calling at 8:00 in the morning. I found something, Tom. A photograph from Seattle, 1926. I need your help tracking down the story behind it. There was a pause. You know, I can’t resist a mystery. Tell me what you’ve got. Elizabeth described the photograph in detail.

The woman, the children, the house, and most importantly, the bruises hidden beneath the loving composition. Thomas listened without interrupting, and when she finished, he was quiet for a long moment. 1926 was a hard time in Seattle. He finally said, “The economy was struggling. Labor disputes, a lot of violence in working-class neighborhoods, domestic situations.

While nobody talked about those things back then, women had no real recourse.” “I know,” Elizabeth said quietly. “That’s why I need to find out what happened. This woman was trying to tell someone something. I can feel it. Send me a copy of the photo. I’ll make some calls to the historical society.

I know a woman there, Sarah Bennett, who specializes in Seattle’s social history from that era. If anyone can help, it’s her. Elizabeth spent the morning in her dark room, making careful prints of the photograph. She created enlargements of specific sections, the woman’s hands, the house’s facade, the children’s faces. Each detail might hold a clue.

By noon, she’d packaged everything and driven to the post office, sending copies to Thomas in Seattle and keeping sets for herself. Back home, she turned to the Seattle City directories. Elizabeth had collected several volumes over the years, finding them invaluable for tracking down families and old photographs.

She pulled the 1926 edition from her shelf and began the tedious work of searching street by street, looking for houses that might match the one in the photograph. The directory listed thousands of residents organized by address without a name or specific location. It was like searching for a particular grain of sand on a beach. But Elizabeth had patience developed through years of meticulous dark room work.

She made notes on neighborhoods that had similar housing stock. Ballard, Georgetown, parts of Capitol Hill. The phone rang late in the afternoon. It was Thomas, his voice tight with excitement. Sarah found something. There was a photographer in Seattle during the 20s, a woman named Dorothy Hayes.

She specialized in family portraits for working-class clients, traveled doortodoor with a portable camera setup. Sarah says Hayes kept detailed ledgers of her work, and they’re preserved in the historical society’s collection. Elizabeth’s heart raced. Can we access them? Sarah’s pulling them now. She’ll go through the entries from June 1926. See if anything matches. But Elizabeth, Thomas paused.

She also said to prepare yourself. If this family went through something traumatic, the records might be hard to read. I understand, Elizabeth said, though her hands trembled slightly as she hung up. She looked at the photograph on her desk at the woman’s determined smile. At those hands that had endured so much, yet still held her children with such gentleness.

I’m going to find your story, Elizabeth whispered to the image. I promise you that. 3 days later, a thick envelope arrived from Seattle. Elizabeth’s hands shook slightly as she opened it, pulling out photocopied pages from Dorothy Hayes’s ledger books. Sarah Bennett had included a note. Found 17 entries from June 1926.

One might be your family. Call me after you read these. The ledger entries were meticulously detailed. Hayes had recorded not just names and addresses, but also brief descriptions of each session, payments received, and often personal observations. Elizabeth spread the pages across her dining table, reading each entry carefully. Most were unremarkable.

Families celebrating new babies, anniversary portraits, children’s birthday photographs, but the 14th entry made Elizabeth’s breath catch. June 18th, 1926. Called to residence on Dawson Street, Georgetown. Client paid in advance, $3. Woman requested portrait with her three children. Noted extensive bruising on arms and wrists.

Client insisted on long sleeves despite warm weather. Husband not present. Woman very specific about wanting copies made quickly. Took extra care with lighting to capture her smile. She wanted the children to remember her happy. Left feeling deeply troubled. Delivered Prince, June 20th. Woman seemed relieved, almost peaceful.

Elizabeth read the entry three times, her chest tight. The address was there. 1247 Dawson Street, Georgetown. And though Hayes hadn’t recorded the name, the description matched perfectly. The timing, the bruises, the urgent request for quick delivery, the specific desire to be remembered as happy. She immediately called Thomas. I found it.

Georgetown, Dawson Street, June 18th, 1926. Sarah’s already ahead of you, Thomas replied. She pulled property records. The house was rented by a family. Woman named Helen, husband named Robert, three children, William, James, and Mary. But Elizabeth, there’s more. His voice dropped. Sarah found newspaper archives.

3 days after that photograph was taken, there was an incident at that address. Elizabeth’s stomach nodded. What kind of incident? Robert was found dead in the house, the official report said he fell down the basement stairs, struck his head, but there were questions. Neighbors had reported hearing arguments, sounds of violence.

Helen claimed he’d been drinking, lost his balance. The police investigated, but couldn’t prove anything else. The case was closed as an accidental death. Elizabeth sat down heavily. The photograph suddenly took on new dimensions. Helen had posed with her children just 3 days before her husband died.

She’d insisted on capturing her smile, on being remembered as happy, those bruises, that determination in her eyes. This wasn’t just a family portrait. This was testimony. This was evidence of survival. What happened to Helen and the children afterward? Elizabeth asked. That’s where it gets harder to track, Thomas said. The family left Seattle within weeks.

Sarah is trying to trace them through census records and city directories from other Washington towns, but it’ll take time. People moved around a lot back then, especially if they were trying to start over. Elizabeth thanked Thomas and spent the rest of the evening studying the photograph with new understanding.

Helen had known she was creating a record, something her children could keep, something that showed love rather than violence. Whether Robert’s death was truly an accident or something else, Helen had ensured her children would remember her not as a victim, but as their protector, smiling and strong. The question now was, where had Helen and her children gone? And had she found the peace and safety she so clearly deserved? Elizabeth couldn’t let it rest.

Over the following week, she threw herself into research with an intensity that surprised her. She contacted census record offices, wrote letters to county clerks across Washington state, and spent hours at the Portland Library reviewing microfilm of old newspapers from surrounding areas. The 1930 census provided the first breakthrough. Sarah Bennett called with excitement in her voice. Found them.

Helen and the three children, William, James, and Mary, living in Tacoma in 1930. She’s listed as a widow working as a seamstress. The children are in school. An address? Elizabeth asked hopefully. Just the ward number, but it’s something. They were living in a working-class neighborhood near the waterfront.

I’m checking Tacoma City directories now. While Sarah worked the Tacoma angle, Elizabeth pursued another lead. She’d noticed something in Dorothy Hayes’s ledger entry, and the photographer had written that Helen seemed relieved, almost peaceful, when she picked up the prince.

That specific language suggested Hayes had intuited something profound about Helen’s state of mind. Elizabeth wondered if Hayes had kept any personal diaries or correspondence. She called the historical society and spoke with Sarah about it. “Actually, yes,” Sarah said. Hayes donated her papers before she died in 1952. “Most of it is business records, but there are some personal letters and a few diary entries.

I can look through them. Two days later, Sarah called back. Elizabeth, you need to come to Seattle. I found Hayes’s diary from June 1926, and there’s an entry about your Helen, but it’s it’s something you should read in person. Elizabeth packed a bag that afternoon and drove north through rain that hammered her windshield all the way to Seattle.

She arrived late evening and checked into a modest hotel near the historical society building. Sleep came fitfully, her dreams filled with that photograph, with Helen’s determined smile and damaged hands. The next morning, Sarah met her in the society’s research room. She was a woman in her 50s with kind eyes and careful hands, the kind of person who understood the weight of historical documents. She laid a leatherbound journal on the table between them.

A juny 1st, 1926, Sarah said, opening to a marked page. Hayes wrote this the day after she delivered Helen’s photographs. Elizabeth leaned forward and read the flowing handwriting. I cannot stop thinking about the woman on Dawson Street. When I returned with her portraits yesterday, she opened the door with such relief in her eyes.

She paid me the remainder, carefully counted coins, and held the photographs as if they were precious treasures. She said, “Now my children will remember me smiling.” Not remember me happy or remember this day, but remember me smiling and as if she were already becoming a memory. I asked if she was well, if she needed help.

She smiled, that same radiant smile from the portrait, and said, “I will be very soon. I’ll be free. Then she closed the door. I stood on that porch feeling I’d witnessed something I couldn’t name. That woman has decided something. Whatever happens in that house, she’s made her choice. I pray she and her children find safety. Elizabeth’s eyes filled with tears. Helen had planned it.

She documented her injuries through that photograph, created a record of her love for her children, and then somehow freed herself from Robert. Whether his death was accident or defense, Helen had known she needed evidence, needed proof of what she’d endured. “There’s more,” Sarah said gently, turning pages. “The 1940 census.

Helen’s still in Tacoma, still working as a seamstress, but all three children are listed with occupations. Williams a mechanic. James is in the Navy. Mary’s a teacher. They made it, Elizabeth. They survived and built lives.” Elizabeth wiped her eyes and looked at the photograph she’d brought with her, now encased in protective plastic.

Helen’s smile seemed different now. Not just loving, but triumphant, defiant. A declaration that she would not let her children remember her as broken. I need to find them, Elizabeth said. The children. They’d be adults now. William would be about 41, James, 39, Mary, 36. They might still be alive.

They deserve to know how their mother protected them, how brave she was. Sarah nodded. Then let’s keep digging. The Tacoma Public Libraryies local history room smelled of old paper and floor polish. Elizabeth and Sarah sat at a corner table surrounded by city directories from the 1930s and 40s, tracing Helen’s family through the years.

The work was painstaking, matching names, addresses, occupations, trying to piece together lives from fragmentaryary records. Here, Sarah said, pointing to a 1938 directory. Mary, she’s listed as a student at the College of Puet Sound. That’s significant for a working-class girl in the 30s to attend college, especially with a widowed mother. Helen made it possible, Elizabeth finished. She worked as a seamstress for years to give her children opportunities.

She felt a deep respect for this woman she’d never met, whose story she was slowly uncovering. They found Williams announcement in a 1941 newspaper. He’d married a local girl named Patricia and settled in Tacoma, working at the shipyards. James’ Navy Service records showed he’d served in the Pacific during the war and returned to Washington in 1946.

Mary had indeed become a teacher, working at Franklin Elementary School in Tacoma through the late 40s. But tracking them into the 1950s proved harder. Postwar mobility made people difficult to follow. Families moved for jobs, for better housing, for fresh starts. The trail seemed to fade. Elizabeth refused to give up.

She spent a week in Seattle and Tacoma visiting churches, schools, veterans organizations. She placed advertisements in local newspapers. Seeking information about Helen and her children, William, James, and Mary, who lived in Tacoma in the 1930s and 40s. Family history research, please contact Elizabeth Morgan. She included her Portland phone number.

The call started coming within days. Most were dead ends, people who’d known different families with similar names. But on the sixth day, a woman named Ruth called. I think I knew Mary, Ruth said, her elderly voice wavering slightly. We taught together at Franklin Elementary in the late 40s.

Is this the Mary you’re looking for? She would have been in her late 20s then, dark hair, very dedicated to her students. Elizabeth’s heart raced. Yes, that could be her. Do you remember anything about her family, her background? Ruth was quiet for a moment, and Elizabeth could hear the rustle of memory being sorted through decades. She was private about her past.

But I remember one day we were talking about our mothers. Mary said hers had been the strongest person she’d ever known, that she’d saved them from something terrible when they were young. She had a photograph of her mother she kept in her desk drawer. She’d look at it sometimes between classes. Said it reminded her what love and courage looked like. Elizabeth felt tears sting her eyes.

Did Mary ever say what happened to her mother? She said Helen died in 1949. Heart trouble. I think Mary took it very hard. Said her mother had worked herself into the grave trying to give them better lives. Ruth paused. Mary left teaching around 1950, moved away.

I lost touch with her after that, but I remember she was a wonderful teacher, especially with the troubled children. She seemed to understand what it was like to be scared, to need protection. After thanking Ruth, Elizabeth sat in her hotel room holding the photograph. Looking at young Mary’s face, maybe six years old in the picture, pressed against her mother’s side, safe in Helen’s protective embrace.

That little girl had grown up to be a teacher who helped frighten children, carrying her mother’s legacy of protection and love forward. But where was Mary now? Where were William and James? They would be in their early 40s, possibly with children of their own, carrying Helen’s story without fully knowing how remarkable it was. Elizabeth returned to Portland, discouraged, but not defeated.

She’d left contact information with dozens of organizations in Washington, placed more advertisements, and asked everyone she’d met to spread the word. Somewhere Helen’s children or their children existed. someone had to remember. Three weeks passed.

Elizabeth returned to her normal routines, developing prints for local clients, teaching occasional photography workshops at the community center, but the photograph remained on her desk, and every evening she found herself studying it, thinking about Helen’s courage, wondering if she’d ever find the family to share what she’d learned. Then, on a Tuesday morning in late December, a letter arrived.

The envelope was postmarked from Eugene, Oregon, with careful handwriting addressing it to Elizabeth Morgan. Inside was a single page written in the same careful script. Dear Mrs. Morgan, my name is William. I saw your advertisement in the Tacoma newspaper. My cousin sent it to me. You’re looking for information about my mother, Helen, and my siblings in me.

I’m not sure why you’re searching for us or what you found, but your ad mentioned family history research. My mother passed away in 1949. My brother, James, died in Korea in 1951. My sister Mary lives in Sacramento with her family. If you found something about our mother, I’d like to know what it is. She was a remarkable woman who gave everything to protect us and give us better lives.

Whatever you’ve discovered, I’m ready to hear it. Please write back or call if you’d like to speak. Yours sincerely, William. He’d included a phone number. Elizabeth’s hands shook as she read the letter three times. She’d found them. After weeks of searching, one of Helen’s children had found her. She looked at the clock, 9:30 a.m., and picked up the phone.

A man answered on the third ring, his voice deep and cautious. Hello. Is this William? This is Elizabeth Morgan from Portland. I just received your letter. There was a pause. Then that was fast. I only mailed it three days ago. I’ve been waiting for this call since I found your mother’s photograph in November. Elizabeth said gently.

I have so much to tell you about her, about what I’ve discovered. But first, I need to ask, do you remember the photograph? June 1926, Seattle. You and your brothers and sister with your mother on the porch. Another pause, longer this time. When William spoke again, his voice was thick with emotion. I remember I was 9 years old.

It’s one of the few photographs we had of Mama. Mary has the original now. She always said it was the most important thing she owned because Mama looked so happy in it. Why? What did you find? Elizabeth took a breath. This wasn’t a conversation to have over the phone. William, I’d like to meet you in person. And there’s a story in that photograph. A story about your mother’s courage that I think you need to hear.

Can I drive to Eugene? Would you be willing to meet with me? Yes, he said immediately. Yes, I want to know. When can you come? They arranged to meet that Saturday at a cafe in downtown Eugene. Elizabeth spent the next three days preparing, making careful prints of the photograph with annotations pointing out the bruises, copies of Dorothy Hayes’s ledger entry and diary, newspaper clippings about Robert’s death, and census records showing how Helen had built a life for her children after Seattle.

She wanted William to understand not just what had happened, but who his mother had been. A woman who’d endured unimaginable pain, yet had posed for a photograph, smiling, had documented her love while quietly planning her freedom, had worked herself to exhaustion to give her children opportunities she’d never had. A Saturday morning dawned clear and cold.

Elizabeth drove south through the Willilamett Valley, the winter landscape, bare but beautiful, and thought about the conversation ahead. How do you tell a man that his mother’s love was even more powerful than he’d known? How do you reveal pain while honoring strength? She’d know when she saw his face.

The cafe was warm and quiet when Elizabeth arrived, just a few customers scattered at tables. She recognized William immediately. He had Helen’s eyes, that same determined look she’d seen in the photograph. He stood when she entered, a tall man in his early 40s, with graying hair and worn hands that suggested manual labor. “Mrs. Morgan?” he asked, extending his hand.

“Elizabeth, please.” She shook his hand firmly, feeling the calluses of someone who worked with his hands. Thank you for meeting me. They sat at a corner table with coffee, and Elizabeth carefully laid out the photograph between them. Not the original, but a high-quality print she’d made. William stared at it, his finger tracing the edge gently.

“I haven’t seen this in years,” he said quietly. “Mary treasures the original. Keeps it in a frame by her bedside. We always thought it captured how much Mama loved us.” He looked up at Elizabeth. “But you found something else, didn’t you?” Elizabeth nodded. She pulled out her folder and began walking him through everything.

Dorothy Hayes’s ledger entry, the diary passage, the dates, the newspaper reports about Robert’s death. She showed him the enlargements she’d made of Helen’s wrists, the visible bruising, the evidence of violence hidden beneath that radiant smile. William’s face went through several transformations as she spoke.

Confusion, then recognition, then a deep, painful understanding. When she finished, he sat back heavily, his eyes fixed on the photograph. “I remember him,” William said finally. his voice barely above a whisper. My father. I remember being afraid of him. Of the sounds of arguing at night, of trying to keep James and Mary quiet so we wouldn’t make him angry.

But the specific details I was so young and mama never talked about those days. She always said we were going to have better lives, that the past was behind us. She protected you, Elizabeth said gently. That’s what this photograph was for. She documented what she’d endured, but she made sure you would remember her smiling, remember her love instead of the violence. William’s eyes filled with tears.

She posed for this 3 days before he died. She was planning something. I think so, Elizabeth said carefully. The police report said it was an accident. Your father fell down the basement stairs. Whether that’s exactly what happened or something else. Your mother made sure she’d created a record first. She was documenting her injuries while showing you her love.

She was incredibly brave, William. He wiped his eyes roughly with his hand. She worked so hard after we moved to Tacoma. Seamstress work, taking in laundry, anything to keep us fed and housed and in school. I never understood where that strength came from. Why she pushed herself so relentlessly. Now I know.

She was making up for lost time, giving us the life she couldn’t give us in Seattle. Elizabeth showed him the census records, the timeline of Helen’s life in Tacoma, years of work, of sacrificing her health so her children could have educations, opportunities, futures. William read through everything, his face a mixture of grief and pride. She died when I was 30, he said.

Heart gave out. The doctor said she’d worn herself down with work, with stress. I blamed myself for not helping more, for not seeing how tired she was. But she always said she was fine, that seeing us succeed was all she needed. She gave you the gift of not knowing how much she’d suffered. Elizabeth said, “That was deliberate.

She wanted you to grow up without that burden, without knowing the depths of what she’d endured and overcome.” “Uh” William looked at the photograph again at his mother’s smile at her hands holding him and his siblings close. Can I Can I get copies of everything you found? I need to show this to Mary. She needs to know. And his voice broke.

She needs to know that every time she looks at this photograph, she’s seeing Mama’s greatest act of love, choosing to be remembered happy instead of broken. Of course, Elizabeth said, pushing the folder toward him. I made these copies for you. The photograph, the documents, everything. Your mother’s story deserves to be known and honored. They sat together for another hour.

William sharing memories of Helen, her laugh, her fierce protectiveness, her insistence that they treat others with kindness, her pride when he learned a trade, when James enlisted, when Mary graduated college. Each memory now took on new depth, new meaning, understood through the lens of what Helen had survived and overcome.

When they finally stood to leave, William embraced Elizabeth tightly. “Thank you,” he whispered. “Thank you for seeing what no one else saw. For caring enough to find us, for giving us back a part of our mother we never knew we’d lost. Elizabeth drove back to Portland that evening with a lighter heart, but also a profound sadness.

She’d given William answers, but also reopened wounds that had never fully healed. 2 days later, her phone rang. It was a woman’s voice thick with emotion. Mrs. Morgan, this is Mary. William called me yesterday and told me everything you found. I’m driving up from Sacramento tomorrow. Can I meet with you? They met at Elizabeth’s house in Portland.

Mary was in her late 30s with Helen’s dark hair and that same intensity in her eyes. She carried a leather portfolio, and when Elizabeth opened her door, Mary was already crying. “I’ve looked at that photograph every day for 28 years,” Mary said as they sat in Elizabeth’s study. The original photograph now carefully laid on the desk between them under proper archival lighting.

“Every single day since Mama died. I thought I knew everything it meant.” But William told me about the bruises, about what you found, and I realized I’d been looking at it wrong my entire life. Elizabeth handed her the magnifying lamp. Look at her hands now, knowing what you know.

Mary bent over the photograph and as the bruises came into sharp focus under the magnification, she let out a sob. How did I never see this? How did I never notice? You weren’t meant to, Elizabeth said gently. Your mother made sure of that. She wanted you to see the smile, the love, the protection.

The bruises were there for someone else to find, for someone in the future who might need to understand what she’d been through. Mary studied every detail. her mother’s wrists, her swollen knuckles, the way the sleeves were carefully positioned. Then she looked up at Elizabeth with red- rimmed eyes. I remember that day now. I was 6 years old.

Mama woke us up early, dressed us in our best clothes, and told us a lady was coming to take our picture. She said it was important that we all looked happy, that we remembered how much we loved each other. “I remember thinking she seemed different that day, scared, but also determined about something.” “Three days later, your father died,” Elizabeth said carefully. Mary nodded slowly.

I barely remember him. William was old enough to have clear memories. James, too, but I only have feelings. Fear, tension, the sense that we had to be very quiet and careful all the time. After we moved to Tacoma, Mama never spoke about him. Never explained what happened. She just said we were going to have a better life, and we did. She worked herself to death to give us that life.

Elizabeth showed Mary the Dorothy Hayes diary entry, the census records, Ruth’s memories of Mary as a young teacher. Mary read everything with tears streaming down her face. I became a teacher because of her, Mary said. Because she taught me that protecting children was the most important thing in the world.

I specialized in working with troubled students, kids from difficult homes. I always seemed to know which ones were scared, which ones needed extra gentleness. Now I understand why. I’d been one of those children, and Mama had shown me how to save them. They talked for hours. Mary sharing memories of Helen that now made heartbreaking sense. Her mother’s nightmares.

her fierce insistence that Mary learn to be independent, her warnings about choosing partners carefully, her relief when Mary married a gentleman who treated her with respect. She was teaching me from her own experience, Mary realized. Every piece of advice, every warning, every conversation about being strong and choosing wisely, she was making sure I’d never end up like she did.

As evening approached, Mary carefully photographed all of Elizabeth’s documentation with a small camera she’d brought. “I want my children to know this story,” she said. My daughter is 14 now. She needs to understand where she comes from, what her grandmother survived, what real strength looks like. Before leaving, Mary took Elizabeth’s hands and hers.

And Elizabeth couldn’t help but notice how similar they were to Helen’s hands in the photograph. Strong and gentle at once. “You gave me my mother back,” Mary said. Not the saint I’d created in my memory, but the real woman. Flawed, hurt, terrified, but brave enough to save us anyway. That’s worth more than you could ever know.

Spring came to Portland with cherry blossoms and rain that washed the city clean. Elizabeth stood in her study preparing for an exhibition at the local historical society. The show was titled Hidden Stories: Women’s Lives and Photographs, and Helen’s portrait would be its centerpiece.

William and Mary had both given permission for the photograph to be displayed along with the full story of what Elizabeth had uncovered. They’d even contributed their own memories and reflections, which would be displayed alongside the image. Mary had written a particularly moving piece about what the photograph meant to her. Now, this portrait was my mother’s way of saying goodbye to who she’d been and hello to who she was becoming. It’s not just a picture of love.

It’s a declaration of survival. The exhibition opened on a Saturday afternoon. Elizabeth was surprised by the turnout. Over 100 people came to see the photographs and hear the stories behind them. But the crowd around Helen’s portrait was especially large. People drawn to that smile, to the story of hidden pain and remarkable courage.

William attended with his wife and two teenage sons. Mary came up from Sacramento with her husband and daughter. They stood together in front of their mother’s photograph, seeing it now with full understanding, not just as a family portrait, but as evidence, testimony, and ultimately a love letter to her children. A young woman in her 20s approached them tentatively.

“Excuse me, are you the family in this photograph?” “Our mother,” Mary said, gesturing to Helen’s image. The young woman’s eyes filled with tears. “I just want you to know I’m in a situation similar to what your mother went through. I’ve been planning how to leave safely, how to protect my son.

This photograph, this story, it’s giving me courage. If she could do it in 1926 with no resources and three children, I can do it now with all the help that’s available today. Mary took the woman’s hand. You can, and if you need help, there are people who will support you. My mother taught me that protecting your child is worth any risk, any sacrifice.

You’re already doing the right thing by planning, by being smart about it. They talked for several minutes. Mary writing down phone numbers for women’s shelters and legal aid services. The young woman clutching the information as if it were a lifeline. Elizabeth watched from across the room, understanding in that moment why she’d been meant to find Helen’s photograph.

The story wasn’t just about one woman’s courage in 1926. It was about every woman who’d ever had to choose between staying in danger and risking everything for freedom. Helen’s decision to document her injuries while showing her love. to create a record that would one day tell her truth resonated across decades because the struggle she faced hadn’t ended.

It had just changed forms. As the exhibition continued over the following weeks, more women came forward with their own stories. Some were historians who’d found similar photographs in their research. Others were descendants of women who’ survived domestic violence in earlier eras.

And some, like the young woman who’d approached Mary, were currently living the reality that Helen had escaped. Elizabeth created a resource board at the exhibition listing modern support services, legal rights, emergency contacts. Helen’s photograph became not just a historical artifact, but a living call to action, a reminder that courage and love could overcome even the darkest circumstances.

3 months after the exhibition, Elizabeth received a letter from the young woman who’d spoken to Mary. She’d left her abusive partner, found safe housing through a women’s shelter, and was rebuilding her life with her son. She enclosed a photograph herself and her young son on the porch of their new apartment, both smiling. On the back, she’d written, “For my son to remember his mother was brave.

” Elizabeth pinned the photograph to her study wall next to Helen’s portrait. Two women separated by 71 years, connected by the same fierce love and determination to protect their children. Two photographs, each capturing not just a moment, but a transformation from victim to survivor, from fear to hope.

That evening, Elizabeth sat at her desk and looked at both photographs in the fading light. She thought about Dorothy Hayes, the photographer who’d intuited Helen’s situation and documented it with care. She thought about Sarah and the archivists who’d preserved records that made this story possible.

She thought about William and Mary carrying their mother’s legacy forward through their own lives and choices. And she thought about Helen herself, that woman with the radiant smile and damaged hands, who’ understood that photographs could be more than memories. They could be testimony, evidence, and ultimately inspiration. Helen had created a portrait of love that was also a portrait of survival.

And in doing so, she’d ensured that her courage would echo through generations. The photograph remained on display at the historical society for 6 months. And during that time, Elizabeth estimated that over 2,000 people saw it. Each person left with Helen’s smile imprinted in their memory, along with the knowledge that sometimes the most powerful act of love is simply refusing to let pain have the last word.

Helen had posed for that photograph knowing it might be the last image her children had of her. She’d chosen to make it a portrait of joy rather than suffering, of protection rather than victimhood. And in that choice, she created something that transcended her own story, a testament to every person who’d ever loved someone enough to be brave, to fight, to survive against impossible odds.

The portrait hung in the Historical Society’s permanent collection now, a small brass plaque beneath it reading, “Helen and her children, Seattle, 1926. Photographed by Dorothy Hayes, a portrait of love, courage, and survival. It was, Elizabeth thought, exactly what Helen would have wanted.

to be remembered not for what she’d endured, but for what she’d overcome.