It was just a portrait of a mother and her daughters, but look more closely at their hands. Dr. James Mitchell had spent 15 years studying photographic archives at the New York Historical Society, but he had never seen anything quite like this. The portrait arrived in a donation box from an estate sale in Brooklyn.

Dozens of glass plate negatives wrapped in yellowed newspaper from 1923. Most showed typical late 19th century scenes, stern-faced merchants, wedding parties, children in Sunday clothes. But one image stopped him cold. Three women stared back through time. A mother, perhaps 40 years old, sat centered in an ornate wooden chair.

Her daughters, who appeared to be in their late teens or early 20s, stood on either side. All three were African-American, dressed in their finest clothes, high-colored dresses with intricate lace work, their hair styled with obvious care. The formal studio backdrop showed a painted garden scene, common for the era.

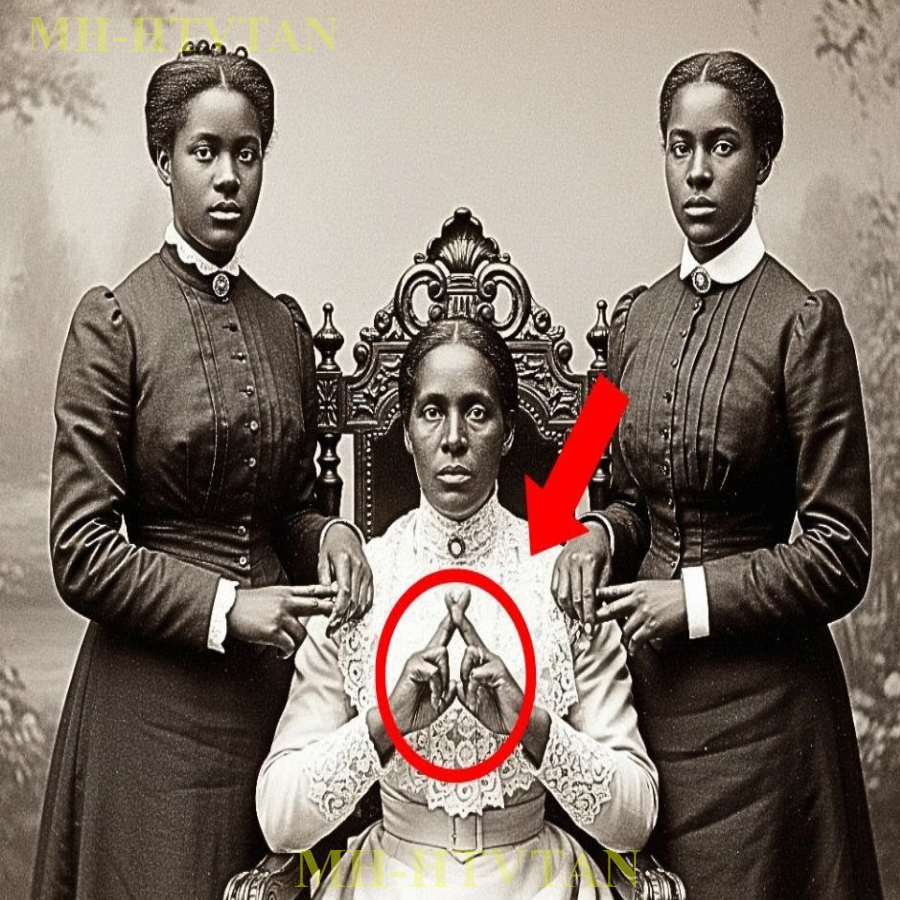

What struck James wasn’t the composition or the subject’s dignified expressions. It was their hands. The mother’s hands rested in her lap, fingers interlaced in an unusual pattern. her right thumb crossed over her left with her index and middle fingers extended while the others curled inward. The daughters each placed one hand on their mother’s shoulders, their fingers arranged in similar deliberate configurations.

James had examined thousands of Victorian era portraits. Subjects typically kept their hands still, folded naturally or resting on props. Photographers of that period demanded absolute stillness during the long exposure time. Every detail was intentional. These hand positions looked too specific, too purposeful to be coincidental.

He lifted the magnifying glass, studying the negative more carefully. In the bottom right corner, barely visible, someone had etched tiny numbers into the glass. NY892247. James couldn’t shake the image from his mind. That evening, he returned to his apartment in the Upper West Side and spread his research materials across the dining table.

He had photographed the glass negative with a high resolution camera, and now the portrait filled his laptop screen in startling clarity. The detail was remarkable for 1892. He could see the texture of the fabric, the small brooch pinned to the mother’s collar, even the subtle differences in the daughter’s features.

But it was the hands that held his attention. He zoomed in until each finger filled the frame. The positioning was unmistakable. Now, this wasn’t random. The mother’s right thumb crossed deliberately over her left, a gesture that required conscious effort to maintain during the exposure. Her extended fingers created a specific shape.

The daughter’s hands on her shoulders mirrored variations of the same theme, fingers bent at precise angles, thumbs positioned with clear intention. James had studied Civil War photography, reconstruction era documentation, and early 20th century social reform movements. He knew that activists and underground networks often used visual signals, specific poses, objects placed in photographs.

Even the way people stood could convey hidden messages to those who knew how to read them. He opened his database of abolitionist and post-emancipation activist networks. The Underground Railroad had used quilts, songs, and symbols. But this was 1892, almost 30 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, 15 years after Reconstruction ended.

What networks still needed secret codes? His phone buzzed. His colleague, Dr. Sarah Chen, a specialist in African-American history, responded to his earlier text, “Free tomorrow morning. What did you find?” James typed back. Something that might rewrite what we know about postreonstruction activism in New York. Bring your sources on property rights and documentation struggles.

Sarah arrived at the historical society at 9 sharp, carrying a worn leather satchel filled with research materials. James had the portrait projected on the wall of the research room, larger than life. The three women gazed down at them with quiet dignity. “Look at their hands,” James said, pointing with a laser pointer, every finger positioned deliberately.

Sarah approached the projection, her eyes narrowing. She set down her bag and pulled out a thick folder. After reconstruction collapsed in 1877, African-American families in the North faced a different kind of battle. Not slavery, but systematic exclusion. Property rights, inheritance, even proof of identity became weapons used against them.

She spread documents across the table. Legal papers, city records, newspaper clippings from the 1880s and 1890s. New York wasn’t the progressive haven people imagine. Black families struggled to maintain property ownership, establish businesses, prove legal marriages. Many had fled the South with nothing but their word.

No birth certificates, no marriage licenses, no documentation. James picked up a yellowed newspaper from 1891. The headline read, “Property dispute in Harlem. Family claims ownership without documentation.” “Exactly,” Sarah continued. “I’ve been researching mutual aid societies from this period. African-American communities created networks to help each other navigate these systems.

They pulled resources to hire lawyers, shared information about sympathetic officials, created their own verification systems when the official ones excluded them. Secret networks, James said quietly. Not secret in the sense of hidden, Sarah corrected. Secret in the sense of parallel, operating alongside official systems using methods that white authorities either didn’t notice or didn’t understand.

James turned back to the portrait. What if this isn’t just a family photograph? What if it’s documentation? The etched numbers in the corner, NY1892247, proved to be the breakthrough. After two days of searching through city directories and business records, James found a reference. Studio 247 belonged to a photographer named Thomas Wright, who operated from a building on 8th Avenue between 1888 and 1896.

The address still existed, though the building had been converted into apartments decades ago. James stood on the sidewalk, looking up at the brick facade, imagining it as it had been. Wright’s studio would have been on the second floor with large north-facing windows to capture the soft, even light preferred for portraits.

Research into Wright himself revealed something unexpected. Thomas Wright was white, born in Massachusetts in 1851, trained as a photographer in Boston. He moved to New York in 1887 and established his studio in a neighborhood that was becoming increasingly diverse. Irish immigrants, Italian families, and a growing African-American community migrating from the south.

But Wright’s clientele was unusual for the era. While most white photographers either refused to photograph black clients or charged them significantly more, Wright’s advertisements appeared in African-American newspapers. His studio welcomed all customers at equal rates. Sarah found an interview Wright gave to a small progressive newspaper in 1894.

He spoke about photography as a tool for dignity and documentation, arguing that every person deserved a quality portrait regardless of their background. Between the lines, James sensed something more, a quiet activism, a deliberate choice to serve a community that others excluded. He was an ally, Sarah said, reading over James’ shoulder.

And if these hand positions are codes, he would have been the one who helped create them, documented them, distributed them. James contacted Dr. Marcus Thompson, a cryptography historian at Columbia University, who specialized in visual communication systems. Marcus arrived at the historical society that afternoon. His curiosity peaked by James’ cryptic phone call.

Victorian era codes often seem impossibly complex to us now, Marcus explained, examining the portrait, but they were usually quite practical for their users. The key is understanding the context, who needed to communicate, what information they needed to convey, and who they needed to hide it from. He photographed the hand positions from multiple angles, then opened his laptop and began creating digital tracings.

Let’s start with the assumption that each hand position represents something specific, not letters. Too complex for a photograph? More likely, categories, confirmations, statuses. Sarah pulled out her research on documentation struggles. What if it’s about identity verification? These networks needed ways to confirm who people were, that they were legitimate members of the community, that they could be trusted with sensitive information. Marcus nodded slowly.

Right. So, the mother’s hand position might indicate her role, family head, network member, someone vouching for others. The daughter’s positions could indicate their status, documented, undocumented, seeking assistance. They worked through the afternoon comparing the portrait to other photographs James had found in the estate salebox.

Three more portraits showed similar hand positioning, always subtle, always deliberate. In one, a couple’s intertwined fingers created a pattern. In another, a man’s hand rested on a Bible with specific fingers extended. “It’s not just one code,” Marcus said finally. “It’s a system, multiple signals that could be combined to convey different meanings.

Someone trained these families how to pose. Someone photographed them deliberately. And someone else, other network members, knew how to read these images.” Sarah made the connection that broke everything open. While researching property rights cases in New York courts from the 1890s, she found a pattern. Dozens of African-American families successfully defended their property claims, obtained identity documents or proved legal marriages, often with the same lawyer representing them.

His name appeared again and again, Robert Hayes. Hayes had an office on West 34th Street. Court records showed he won an unusual number of cases for black clients during an era when such victories were rare. More significantly, he often submitted photographic evidence, portraits of families, documentation of their respectability, proof of their presence in the community.

He was using Wright’s photographs in court, James realized, not just as evidence of identity, but as verification of community standing. These families were photographed, their images were cataloged, and when they needed documentation, Hayes could present these portraits to judges. But there was more. In Hayes’s archived case files at the New York Public Library, Sarah found letters.

correspondence between Hayes and other activists, teachers, ministers, business owners, discussing verification protocols and community documentation systems. One letter dated March 1893 was particularly revealing. Hayes wrote to a minister in Brooklyn, “We have expanded our photographic documentation to include 73 families.” Mr.

Wright continues to provide his services at minimal cost. The hand positioning system allows us to encode essential information that can be verified later. Each portrait serves as both dignified representation and practical identification. James sat back, stunned. They built an entire parallel documentation system. When official channels failed these families, they created their own, and they hid it in plain sight, Sarah added.

These portraits looked like ordinary family photographs. No one examining them casually would see anything unusual. But to network members who knew the code, each portrait contained vital information. With the network structure emerging, James became obsessed with identifying the three women in the original portrait.

The estate sale had come from a brownstone in Bedford Stson, Brooklyn, a neighborhood with deep African-American roots. The historical society’s donor records provided the seller’s name, Patricia Johnson, who had inherited the property from her grandmother. James called Patricia that evening. She was 72 years old, sharpvoiced, and initially skeptical of his interest in old family photographs.

But when he described the portrait in detail, her tone changed. “My great-g grandandmother,” she said quietly. “That’s Elellaner. Elellanar Morrison. The daughters would be my grandmother Ruth and her sister Grace. Can you tell me about them? James asked. Patricia was silent for a moment. Ellaner was born enslaved in Virginia.

Came north after the war with Ruth who was just a baby. Grace was born here in New York. Ellaner worked as a seamstress. She was known for her skill with lace and fine embroidery. Supported the family that way. Did she ever mention being part of any organizations, community groups? She was involved in her church, Patricia said. And she helped people.

That’s what my grandmother always said. Ellaner helped families with paperwork. finding housing, connecting with lawyers. She seemed to know everyone, how to navigate every system. James’ pulse quickened. Patricia, I think your great-grandmother was part of something significant, a network that helped African-American families document their identities and protect their rights after reconstruction.

Patricia was quiet again. When she spoke, her voice was thick with emotion. I always knew she was special, but we lost so much history. After she died in 1919, the family scattered. My grandmother rarely talked about those early years. With Patricia’s permission, James and Sarah began tracing Elellanar Morrison’s connections.

Church records from Bethl Church in Brooklyn showed Elellanar as a member from 1879 until her death. She served on the Ladies Aid Society, which officially provided charity to needy families. But the meeting minutes revealed something more structured. The society kept careful records of families they assisted, names, ages, circumstances, needs, but certain entries included notations that made no sense in context, numbers, and letter codes that seemed arbitrary until Sarah realized they corresponded to Thomas Wright’s numbering system. They were

cross- referencing, she explained to James. The Church Society identified families who needed documentation. Wright photographed them with the appropriate handcodes. Hayes used the photographs in legal proceedings. And the church records kept track of everything hidden in plain sight within charity work documentation.

James found more photographs in Wright’s archive. The historical society had acquired his entire collection in 1923 after his death, but no one had properly cataloged it. Dozens of portraits showed the hand positioning system. Families photographed between 1890 and 1896. Each image carefully numbered, each one documenting people who had been systematically excluded from official records.

They identified other network members. A teacher named Samuel Brooks who helped families obtain school records for their children. A clerk in the city property office named Mary Chen who processed deeds and made sure paperwork was properly filed. A minister named Reverend James Washington who performed marriages and provided certificates when official channels refused.

Each person had taken quiet risks, used their position to help, operated within a system designed to exclude the people they served. Together they had created something power a shadow archive that preserved dignity and protection when official America offered neither. Three months into their research, James and Sarah organized an exhibition at the historical society.

They displayed 20 portraits from Wright’s collection, each showing the hand positioning system, each accompanied by the story they had uncovered about the family photographed. Patricia Johnson attended, seeing her great-g grandandmother’s portrait properly honored for the first time. She brought her daughter and granddaughter.

Four generations of Elellanar Morrison’s descendants standing before the image that had started everything. But the exhibition’s most powerful moment came when other descendants arrived. James and Sarah had located families connected to 12 of the photographed individuals. Each had pieces of the story, fragments of oral history, old letters, faded documents that suddenly made sense within the network’s context.

An elderly man named Thomas Hayes stood before a portrait of his great-grandfather, the lawyer Robert Hayes, photographed with his hands positioned in the same deliberate code. “I always heard he helped people,” Thomas said quietly. “But I never knew the extent. Never knew he was part of something this organized. A woman named Grace Brooks examined a portrait of Samuel Brooks, the teacher.

My family said he was arrested once in 1895 for helping a family obtain false documents, but the charges were dropped. And looking at this now, I don’t think the documents were false. I think he was helping people get the documentation they deserve, but were denied. The New York Times covered the exhibition.

The article ran with the headline, “Hidden in plain sight, how postreonstruction activists built a secret documentation network.” Within days, historians from across the country contacted James, sharing similar findings from their regions. parallel networks in Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, all operating during the same period, all using subtle codes and photographs to document and protect African-American families navigating hostile systems.

6 months after discovering the portrait, James stood in the historical society’s conservation lab, carefully handling the glass plate negative. They had digitally restored dozens of Wright’s photographs, each image now preserved and accessible to descendants and researchers. The mother and daughter’s portrait had become iconic, reproduced in textbooks, featured in documentaries, displayed in museums.

But for James, its power remained personal. He thought of Eleanor Morrison, born enslaved, who had built a life of dignity and purpose in New York, who had helped countless families navigate a system designed to exclude them, who had posed for this photograph with her daughters, their hands carefully positioned in a code that would preserve their place in history.

Patricia Johnson had donated Elellanar’s personal papers to the historical society, letters, a diary, business records from her seamstress work. In the diary, Elellanar wrote about the photograph, had our portrait made today. Mr. Wright is a kind man, understands what we are building. The girls were nervous, but I told them this picture will matter.

Someday people will see what we did here. She had been right. The photograph had mattered. It had preserved not just their images, but evidence of their resistance, their ingenuity, their refusal to be erased. Sarah had traced 63 families through the network, documenting how they had obtained property deeds, legal marriages, business licenses, and school records, fundamental rights that should have been automatic, but required elaborate workarounds to achieve.

The network had operated from approximately 1888 to 1897, helping hundreds of families before gradually dissolving as some activists died, others moved and new systems emerged. Thomas Wright had died in 1923, his contribution largely forgotten. Robert Hayes had continued practicing law until 1910. Elellanar Morrison had lived to see her daughters married and established, her work continued by others.

The network hadn’t solved systemic injustice, but it had provided practical help to people who needed it desperately. James met regularly with descendants now, collecting oral histories, connecting families who shared this hidden heritage. The portrait had become more than historical evidence. It was a bridge between generations, proof that their ancestors had been resourceful, connected, and determined to create justice when official America denied it.

He thought of Ellanar’s hands, positioned deliberately in that Brooklyn studio in 1892, her fingers creating a code that would outlive her, that would carry her story across more than a century. In the end, the simplest gestures could hold the most profound truths. Sometimes you just needed to look closely enough to see