October 24th, 1944. The Philippine Sea. Lieutenant Koshi Ogawa was drowning. His Zero fighter shot down by an American Hellcat had disappeared beneath the waves 30 seconds ago. Now he floated in burning oil, watching the USS Lexington. The massive American carrier he had been trying to destroy steaming straight toward him.

He knew what came next. They would mack gun him in the water. That is what you did to enemy pilots. He had done it himself. Off Guadal Canal, quick burst, bubbles, over. But here is what happened instead. Something that would haunt Kioshi for the next 47 years of his life. The deck crew threw him life rings.

While the battle was still raging, while Japanese aircraft were still attacking their carrier group, while his wingman somewhere in the smoke-filled sky above was trying to kill these same Americans who were now trying to save his life. This moment shattered everything Koshi’s instructors had told him about Americans.

To understand why, we need to go back 6 hours to the morning he climbed into his zero for what he believed would be a glorious death. Kioshi had been awake since 0400 hours at Mabalacat Air Base in the Philippines. 26 years old, three years of combat experience, 73 missions, zero ace with six confirmed kills. But this morning was different.

His squadron commander had gathered them in the briefing hut and spoken the words every naval aviator had been trained to hear. Today, some of you may be asked to make the ultimate sacrifice. The Americans had returned to the Philippines with over a hundred ships. The Imperial Japanese Navy was throwing everything at them, including tactics that six months ago would have been unthinkable.

Koshi had heard the rumors about the kamicazi units. Pilots deliberately crashing into American ships. But this morning’s mission was conventional. Attack the American carrier group. Spotted 200 m northeast. Return to base. Rm. Repeat until you died. or the Americans went home. At 0645 hours, 12 zeros lifted off.

Koshi flew wing position to his close friend, another ace with steady hands and good instincts. They had flown together for 18 months, saved each other’s lives three times between them. His wingman’s last words over the radio, “If I go down, do not try to rescue me. Just kill as many as you can.” Standard warrior sentiment. Death before dishonor. Never surrender.

Now 6 hours later, floating in burning oil and seawater, Koshi wondered if his friend had known something he did not. The attack had started well. They had found the American carrier group at 10:34 hours, four fleet carriers, six escort carriers, dozens of destroyers and cruisers. The sky was a chaos of anti-aircraft fire.

Black puffs of flack filled the air. Koshi had picked his target, the Lexington, the biggest carrier, steaming at the center of the formation. He pushed his Zero into a steep dive, throttle full, the airframe screaming, tracers from the carrier’s guns reaching up toward him, and that is when the American Hellcat found him. He never saw it coming.

One moment, he was diving toward his target. The next, his engine was dying, oil spraying across his windscreen. His left aileron shot away. Kioshi tried to pull up, failed. The Zero shuddered, stalled, and began its final spiral toward the water. He yanked the canopy release. The wind ripped at his face. His parachute deployed barely.

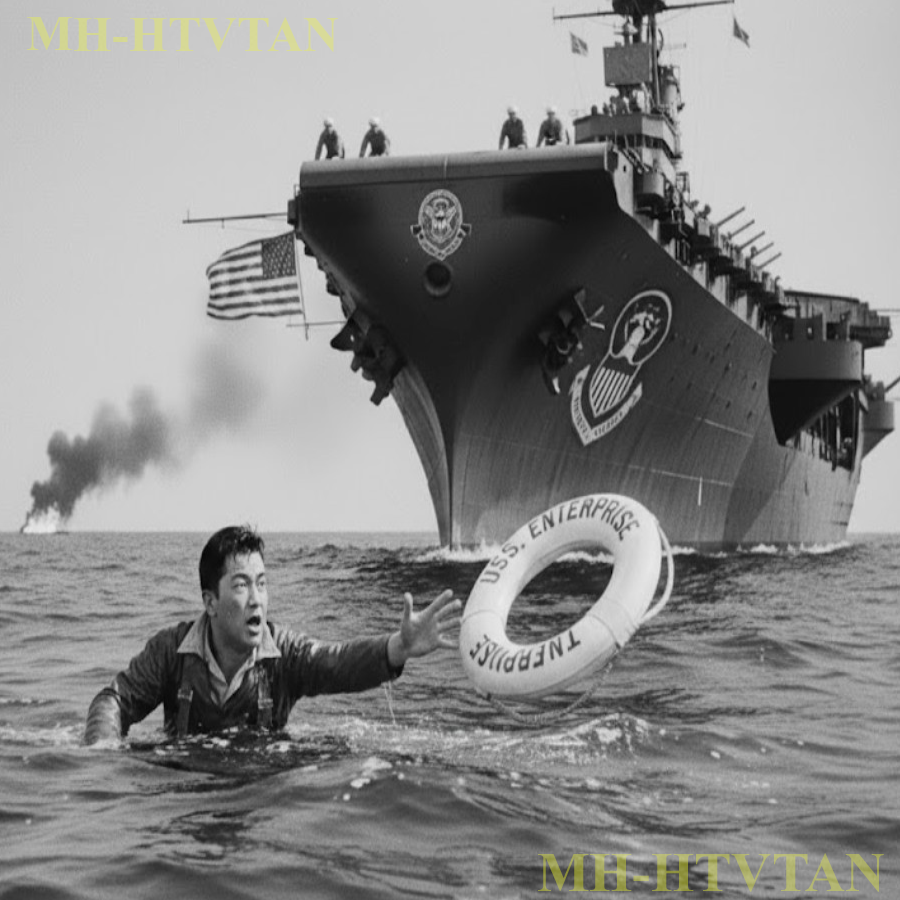

Two panels were shredded. The descent was too fast. The water hit him like concrete. Seaman first class Tommy Morrison from Tulsa, Oklahoma was manning his station on the portside catwalk when he saw the zero pilot hit the water about 400 yards off the bow. Tommy was 19 years old. This was his first major naval battle until 5 seconds ago his job had been loading ammunition for the gun crews trying to kill enemy pilots.

Now he was watching one of those pilots struggle in the water. And Tommy did something that could have gotten him court marshaled. He grabbed two life rings from the catwalk railing and he threw them. One fell short. The other landed 10 ft from the Japanese pilot. Morrison, what the hell are you doing? Chief Petty Officer Daniel Kowalsski appeared beside him, red-faced, shouting over the guns.

He is going to drown, Chief. He is the enemy. He is not shooting at us anymore. For three seconds, Kowalsski stared at Morrison. Then at the Japanese pilot weakly swimming toward the life ring, then back at Morrison. Then Chief Kowalsski did something that would define the rest of his 20-year naval career.

He grabbed another life ring and threw it, too. If you are going to do something stupid, Morrison, do it right. Somebody get a rope. Koshi could not believe what he was seeing. The orange life ring floated 3 m away. American markings. USS Lexington stencileled in black letters. This had to be a trick. They would let him grab it, then machine gun him for sport.

He had heard stories about American cruelty. How they tortured prisoners. How they took no prisoners at all in the Pacific. But he was drowning. His flight suit was dragging him down. Blood from a gash on his forehead ran into his eyes. His left arm was not working. Dislocated shoulder from the bailout. Koshi made his decision. He swam for the life ring.

His working hand closed around it. He hugged it to his chest and waited for the bullets. They never came. Instead, a rope splashed into the water beside him. Then voices, American voices, shouting something he could not understand. But the tone was not angry. It was urgent, encouraging.

They were telling him to grab the rope. Koshi looked up at the carrier deck. At least 30 Americans lined the railing. Some were still manning the anti-aircraft guns. The battle was not over, but others had stopped to watch. A Japanese pilot holding an American life ring while American sailors tried to pull him to safety while the battle still raged.

This made no sense. No sense at all. But Koshi grabbed the rope. They hauled him up the side of the carrier. His shoulders screamed the dislocated one especially, but he held on. Hands grabbed him as he reached the deck. strong hands pulling him over the railing, setting him down. He collapsed immediately and waited for the beating.

It did not come. Instead, someone cut his flight suit away. Someone else wrapped a blanket around his shoulders. A young sailor with red hair pressed a canteen to his lips. Fresh water. Actual drinking water. Koshi was so shocked he forgot to drink. The red-haired sailor Morrison tilted the canteen more insistently. Come on, buddy.

You have got to drink. You are in shock, buddy. Around him, the battle continued. The 40mm guns were still firing. Somewhere overhead, a zero streaked past. So close Koshi could see the rising sun painted on its fuselage. So close he recognized it. His wingman, still alive, still fighting, still trying to kill these people who were saving Kioshi’s life.

The cognitive dissonance was overwhelming. Chief Kowalsski knelt beside him. The older man’s face was weathered. Serious but not cruel. He gestured to his own shoulder, then pointed at Kioshi’s. Shoulder is dislocated. Doc is coming. It is going to hurt. Koshi understood the gesture. He nodded.

A Navy corman arrived, maybe 22 years old, with gentle hands. He examined Kyoshi’s shoulder, then looked at Kowalsski. I can pop it back in here or we can take him to sick bay. Here we are still at battle stations. The corman positioned himself behind Koshi, gripped his arm, and said, “On three, one, two.” He did it on two.

The pain was extraordinary. Koshi screamed, but then it vanished, replaced by a deep ache that was somehow better. The corman wrapped it with remarkable gentleness. Then he cleaned the gash on Koshi’s forehead and bandaged it. Professional, competent, exactly as careful as he would be with an American sailor. You are going to be okay, the corman said, patting Koshi’s good shoulder.

You are safe now. Koshi understood the tone, if not the words. These men were not going to kill him. The realization made him weep. They moved him below deck as soon as the battle ended. Two sailors supported him, Morrison on one side, another young sailor on the other. They took him to Sick Bay where Lieutenant Commander James Hutchinson, the ship’s senior medical officer, examined him thoroughly.

Hutchinson was maybe 40 with gray at his temples and crows feet around his eyes. He reminded Koshi of his own father. Same careful hands, same focused expression, the examination revealed. Dislocated shoulder now reset. Three cracked ribs, multiple contusions, minor burns, and significant dehydration. Hutchinson gave orders, and Corman jumped to execute them.

They gave Koshi morphine for the pain, put him in a clean bunk with actual sheets, gave him more water, then soup, chicken soup, hot and salty, with actual pieces of chicken. Koshi had been eating rice balls and dried fish for 3 months. This soup was a revelation. He ate three bowls. Nobody stopped him.

That evening, Morrison returned with something wrapped in wax paper. He sat on the edge of Koshi’s bunk and unwrapped it. A Hershey chocolate bar. “For you,” Morrison said, pantoiming eating. Koshi took the chocolate. He had never seen an American chocolate bar before. He broke off a square and ate it slowly.

It was sweeter than any Japanese confection. Creamy, rich. He closed his eyes. Morrison grinned. Good, right? My mom sends me a box every month. I have got plenty. Koshi did not understand the words, but he understood the gesture. He bowed his head. Ariato goas. Morrison’s grin widened. Hey, you are welcome, pal. They sat together in companionable silence while Kioshi finished the chocolate.

Above them, the ship’s engines hummed. Around them, American sailors went about their duties. Nobody glared at Koshi. Nobody spat at him. Several nodded respectfully as they passed. This was not what Tokyo had promised him. Over the next 3 days aboard the Lexington, Koshi’s physical condition improved rapidly, but his mental state was in turmoil.

Everything he had been taught about Americans was a lie. They were not cruel. They were not barbarians. They did not torture prisoners or execute them. They followed rules something called the Geneva Convention that the coremen kept mentioning. They treated wounded enemies the same as wounded Americans. One afternoon, Dr. Hutchinson sat beside his bunk with a translator, a Japanese American Navy interpreter named George Suzuki, who had grown up in California.

Through Suzuki, Hutchinson explained, “Under the Geneva Convention, prisoners of war must be treated humanely. You will receive the same medical care as our own wounded. You will be fed the same rations as our sailors. You will not be tortured or mistreated. Do you understand? Koshi nodded slowly, then asked, “Why?” Hutchinson considered the question.

“Because that is what civilization means, son. We are at war with your government, not with you personally. You are a combatant who is now out of action. You deserve dignity. The word hit Koshi like a physical blow. When had anyone in the Imperial Japanese Navy used that word about an enemy? On the fourth day, Suzuki brought Koshi paper and a pen. You can write to your family.

Let them know you are alive. The International Red Cross will deliver it. Koshi stared at the blank paper. You would let me do this. Geneva Convention requires it. Your family has a right to know your status. Koshi wrote carefully, “Honored mother and father, I am alive and uninjured.

I am a prisoner of war aboard an American ship. They are treating me well. I am receiving medical care and adequate food. Please do not worry for my safety.” “Your son, Koshi.” He folded the letter and gave it to Suzuki, certain it would never be delivered. The letter reached his parents 3 months later. His mother kept it for the rest of her life.

Morrison visited frequently, bringing chocolate or cookies or just conversation. He would sit on the bunk and talk, even though Koshi understood maybe one word in 20. One afternoon, Morrison pulled out his wallet and showed Koshi a photograph. A pretty girl with dark curls standing beside a 1938 Ford. “Betty,” Morrison said, pointing to the girl. “My girl back in Tulsa.

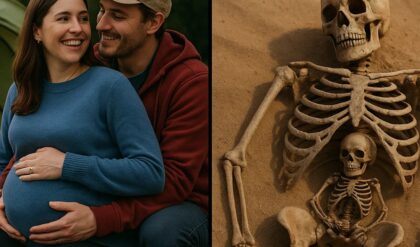

We are getting married when I get home.” Koshi understood Betty and Tulsa and something about marriage. He smiled and nodded. Then Morrison asked through gestures, “Did Koshi have anyone?” Koshi thought of his sweetheart back home, his childhood friend. They had talked about marriage before he enlisted, but he had not seen her in 3 years.

Did not even know if she was still alive. He shook his head sadly. Morrison squeezed his shoulder sympathetically. Just a simple gesture of human connection, but it meant everything. On Koshi’s sixth day aboard, something remarkable happened. Morrison helped him up to the mess deck where maybe 40 American sailors were relaxing, some playing cards, some writing letters, some just talking, and nobody stopped him from sitting down with them.

He sat in a corner, Japanese pilot in American prisoner of war denims, while sailors who had been shooting at him a week ago played poker three feet away. One sailor, a kid from Nebraska, offered him a hand of cards. They played gin rummy for an hour, communicating entirely through gestures and laughter. Koshi won twice. The sailor won three times.

Neither cared about the score. It was the most normal Koshi had felt in 3 years of war. The American military’s treatment of prisoners did not happen by accident. It was doctrine drilled into every service member from day one. General Dwight Eisenhower had made it explicit. The Allied forces serve under our standards of conduct.

We respect the rules of warfare and we respect the dignity of enemy prisoners because that is what separates us from the regimes we are fighting. General George Marshall had been even more direct. How we treat enemy prisoners will determine how enemy forces treat our prisoners. Moreover, it will determine what kind of peace we can build after victory.

They understood something prophetic. The war would end eventually. What mattered was what came after. But beyond strategy, there was something deeper American cultural values. Morrison had not thrown that first life ring because of the Geneva Convention. He had thrown it because his mother had raised him to believe that human life had value, even enemy life.

Chief Kowalsski had backed him up because 20 years in the Navy had taught him that discipline meant following the rules even when it was hard, especially when it was hard. Dr. Hutchinson had treated Koshi’s wounds with care because that is what doctors did. The oath said, “Do no harm.

” It did not specify except enemies. Years later, interviewed for a documentary, Koshi would say, “In seven days aboard that American ship, I learned more about the United States than three years of propaganda had taught me. Tokyo told us Americans were weak, decadent, cowardly. But I watched men throw me life rings while their ship was under attack.

I watched a doctor treat my wounds as carefully as he would treat his own crew. I watched a farm boy from Oklahoma share his mother’s chocolate with someone who had been trying to kill him an hour earlier. That is not weakness. That is the strongest thing I have ever seen. Koshi was not alone. Thousands of Japanese PS in American custody experienced similar treatment.

They were held in camps that provided adequate food, medical care, and shelter. They were allowed to write home. They were not beaten or executed. The contrast with Japanese treatment of allied PSWs was stark and deliberate. American survival rate in Japanese custody 63%. Japanese survival rate in American custody 96%. Those numbers told a story about values.

By war’s end, the United States held approximately 425,000 enemy prisoners from all theaters, German, Italian, and Japanese. The vast majority survived captivity and returned home. Many of them, like Koshi, received better medical care as prisoners than they had received from their own militaries.

Many gained weight in captivity. Many learned English through education programs offered in the camps and many decades later would return to the United States as immigrants or visitors would bring their children and grandchildren to see the country that had treated them with dignity when they had expected death.

One German P held at Camp Richie in Maryland later said, “I became a prisoner of war in 1944. I became a friend of America that same year.” That friendship would reshape the post-war world. After seven days aboard the Lexington, Koshi was transferred to a larger P facility on Guam, then eventually to a camp in Hawaii. He spent the rest of the war there almost 11 months working on agricultural details, attending English classes, and slowly rebuilding his understanding of the world.

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, Koshi wept, not from shame, though there was some of that, but from relief. The war was over. He could go home. Repatriation took another four months. In December 1945, Koshi Ogawa stepped off a transport ship in Yokohama and into a country he barely recognized. Japan was shattered, cities burned, economy destroyed, millions dead.

But Koshi came home healthy, well-fed, educated, and fundamentally changed. He found his sweetheart. She had survived, working in a textile factory in Osaka. They married in 1947, had three children. Koshi worked as a translator for the American occupation forces, then later for Japanese companies doing business with American firms.

And every year without fail, Koshi tried to find the Americans who had saved his life. It took him until 1968, 24 years later, but he finally located Tommy Morrison. Morrison was living in Tulsa, working at an aircraft plant, married to his Betty with four kids. Koshi wrote him a letter. Morrison wrote back immediately.

In 1969, Koshi Ogawa flew to Oklahoma. Morrison met him at the airport. Two men, one who had been trying to kill the other shipmates, one who had thrown a life ring anyway, embraced like brothers. Koshi stayed with the Morrison family for 2 weeks. He met Betty, met the kids, ate Betty’s pot roast, watched American television, played with the Morrison grandchildren, and on the last night, sitting on Morrison’s back porch with beers in their hands, Koshi finally asked the question that had haunted him for 25 years. Why did you throw me that

life ring? You could have let me drown. Morrison thought about it for a long time. Finally said, I do not know, Kyoshi. It just seemed like the right thing to do. You were not shooting at us anymore. You were just a guy drowning, so I helped. It just seemed like the right thing to do. Koshi nodded. That answer said everything about America that needed to be said.

The American treatment of prisoners during World War II paid enormous dividends. Germany and Japan, America’s mortal enemies in 1945, became its strongest allies by 1955. The Marshall Plan rebuilt Europe. The American occupation of Japan created a democratic society. Former enemies became trading partners, then friends, then defenders of the same democratic values America had demonstrated even during wartime.

Chief Kowalsski was right, though he did not know it when he threw that second life ring. You win wars with weapons. You win peace with values. The Japanese soldiers who experienced American pow camps went home and told their families what they had seen. The German prisoners who worked on American farms and made friends went home and advocated for democracy.

The Italian soldiers who received care in American hospitals went home and helped rebuild democratic Italy. You cannot build those kinds of relationships with propaganda. You build them by treating people with dignity when you do not have to. In 1991, Koshi Ogawa was invited to speak at the USS Lexington Museum in Corpus Christi, Texas.

The carrier, the same one that had pulled him from the water, had been decommissioned and turned into a floating museum. Koshi, now 73 years old, stood on the same deck where Morrison had thrown him a life ring. He ran his hands along the railing, looked out at the water, and told the assembled crowd, “I came to this ship expecting to die in glory.

Instead, I learned to live in dignity. That education changed my life, changed my children’s lives, changed my grandchildren’s lives.” American sailors saved one Japanese pilot on one October day in 1944. But the lesson that pilot learned that even in war, human life has value. That lesson has echoed through three generations of my family.

My son studied in America. My daughter married an American. My grandchildren are American citizens. That is what Tommy Morrison and Chief Kowalsski and Dr. Hutchinson created when they threw those life rings. Not just one saved life. an entire family of people who believe in the American ideals of human dignity. That is the real victory of World War II.

The crowd gave him a standing ovation that lasted 3 minutes. Wars end. That is the fundamental truth. People forget when the shooting starts. The bullets stop, the treaties get signed, the soldiers go home, and then the real work begins. Building a peace that lasts longer than the war did. You cannot build that kind of peace through humiliation or revenge.

The Treaty of Versailles tried that after World War I harsh terms, crushing reparations, national humiliation. 20 years later, the world was burning again. But treating enemies with dignity, that creates something different. That creates former enemies who remember your values, not your vengeance. Who want to emulate your system rather than destroy it.

Tommy Morrison’s Throne Life Ring did not just save Koshi Ogawa. It created a Japanese translator who helped American occupation forces. A father who raised children to admire American values. A grandfather to American citizens who serve in the US military today. That is the long game of war. Not just defeating enemies, transforming them into allies.

And it starts with the simple decision in the middle of battle when you have every reason not to to recognize the humanity in someone trying to kill you. Koshi Ogawa climbed into his Zero Fighter on October 24th, 1944, expecting glory and death. He fell into the Philippine Sea expecting execution. He climbed aboard the USS Lexington expecting torture.

Instead, he found humanity. chocolate bars, gin rummy games, a life ring thrown by a farm kid from Oklahoma who just thought drowning men should be saved. That changed everything. Koshi died in 2003 at age 85, surrounded by his American grandchildren. Tommy Morrison died in 2007, still keeping Koshi’s letters in his desk drawer.

Both men spent their final decades telling the same story to anyone who would listen. War tests your values. when they are hardest to keep. And the side that keeps them wins more than battles. They win the peace. If your family has P stories from either side, share them in the comments. These stories matter.

They remind us that even in humanity’s darkest moments, someone can still throw a life ring. Thank you for watching.