March 17th, 1945. San Francisco Harbor. Dawn broke cold and gray over the water. Fog thick enough to blur the line between sea and sky. Below the deck of a rusted transport ship, 47 Japanese women huddled in darkness, listening to American voices above. Their scalps bled from 18 months of scratching.

They could feel things crawling through their hair even now in this final moment before whatever came next. They had been told what Americans did to Japanese prisoners. They had been warned about the cruelty, the torture, the humiliation that awaited captured women. When the hatch opened and light poured down into the hold, they braced for the worst.

What they saw instead was a young American nurse with kind eyes who spoke five words through a transl.

We’re going to help you. And in that moment, as American hands reached down, not to strike, but to assist. Each woman realized something more terrifying than any beating could ever be. The enemy wasn’t behaving like an enemy at all. The propaganda had been so clear, so certain.

Americans were demons with blue eyes who delighted in Japanese suffering. Every poster in Tokyo, every radio broadcast, every military briefing had reinforced this truth. Japanese soldiers captured by Americans faced torture and death. Japanese women faced worse. It was why so many had chosen suicide over surrender. It was why mothers on Saipan had thrown their children from cliffs rather than let them fall into American hands.

The entire nation had been taught that Americans were monsters wearing human skin. But the soldier standing before nurse Yoko Tanaka as she climbed onto the deck wasn’t a monster. He was a boy, 19 at most, with red hair and freckles and hands that trembled as he held out a wool blanket. His eyes weren’t cruel. They were nervous, uncertain, almost apologetic, as if he knew how terrifying this moment was for her.

As if her fear mattered to him. Yoko had served as a military nurse in Manila when the city fell. She had been 23 years old, trained in modern medicine, fluent in English, proud to serve the Empire. She remembered the chaos of the collapse, the desperate evacuation attempts, the moment when she realized there was nowhere left to run.

She had been captured along with dozens of other women nurses, clerks, radio operators, teachers who had followed the Japanese military across the Pacific. For 18 months they had been moved from camp to camp, each one worse than the last. 18 months of hunger and cold, and the constant crawling horror of life that no amount of scratching could eliminate.

They had expected to die far from home. They had made peace with it. What they had not expected was to be brought to America itself, to the enemy’s homeland, where surely the worst torments awaited them. The 47 women clustered together on the deck like frightened birds, skeletal frames draped in ragged uniforms that hung loose on bodies that had forgotten what it meant to be full.

Some could barely walk. Others shook with fever. All of them waited for the cruelty to begin. But the smell that drifted across the water from the port facilities wasn’t the smell of torture or death. It was coffee, fresh bread, frying bacon, aroma so rich and impossible that several women whimpered. One began to cry.

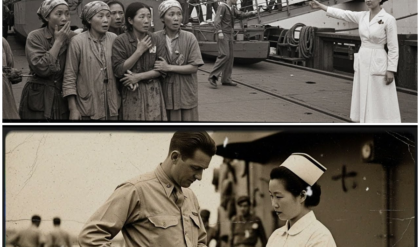

They hadn’t smelled real food in so long that their minds struggled to identify each scent, struggled to believe such abundance could exist in a world that had been nothing but scarcity for so long. Lieutenant Sarah Williams approached with a clipboard, 26 years old, from a small town in Ohio, where she had worked as a school teacher before the war, turned her into something harder.

She looked at Yuko’s matted hair and bleeding scalp, and saw the lice visible, even from 3 ft away, tiny dark specks crawling through tangles that had become solid masses of filth and despair. Sarah’s eyes filled with something Yoko had never expected to see in an enemy’s face. Not hatred, not contempt, compassion. Through a Japanese American transl, Sarah spoke in a voice that was firm, but gentle.

Welcome to the United States. You’re safe now. We’re going to take care of you. Yoko didn’t understand all the words, but she understood the tone. It was the same tone she had once used with frightened patients in Manila, back before the war had turned her into something less than human, back when healing had still seemed to matter.

They were loaded onto buses, clean buses with intact windows and cushioned seats. No chains, no ropes. No guards with bayonets pointed at their backs. Just American soldiers who helped them climb aboard, who steadied those who stumbled, who closed the doors gently as if violence had never occurred to them. The women sat in stunned silence as the buses rolled through San Francisco streets, and what they saw through those windows made no sense at all.

Buildings stood whole. Windows gleamed in the pale morning sunlight. People walked on sidewalks carrying packages, shopping as if there was no war, as if the Pacific wasn’t burning, as if the world hadn’t been torn apart. Cars filled the streets. Shop windows displayed goods behind clean glass. Neon signs advertised products with names Yoko couldn’t read.

Children played in a small park. A woman pushed a baby carriage. Two men laughed at some shared joke. Life. Normal life. Impossible life. Yoko pressed her face to the glass and felt something crack inside her chest. In Japan, cities were burning. Her mother’s last letter received a year ago and read until the paper fell apart had described food shortages and blackouts and neighbors who had stopped smiling.

Tokyo was being bombed night after night. People were eating grass and tree bark. Children were being evacuated to the countryside to escape the firestorms. Her country was dying. But here on the enemy’s soil, the war seemed like something happening on another planet. Here there was abundance. Here there was peace. Here the American people lived as if victory was so certain they didn’t even need to think about it.

The buses carried them past factories with smoke stacks pumping out production, past warehouses stacked with goods, past rail yards filled with freight cars. The industrial capacity was staggering, overwhelming. In that moment, watching America’s wealth roll past the windows, Yoko understood something that made her stomach turn. Japan had already lost.

Maybe Japan had always been going to lose. The propaganda had lied about American weakness the same way it had lied about American cruelty. The facility sat on the city’s outskirts, low buildings surrounded by wire fencing. But even this was different from anything Yoko had experienced. The buildings were painted.

Gardens grew near the entrance. flowers and bright spots of color that seemed almost defensive in their cheerfulness. One of the guards was chewing gum. He blew a small bubble as they passed, then grinned at his own foolishness. Yoko had never seen a soldier do anything so casual while on duty. In the Japanese military, such behavior would have earned a beating.

Inside they were divided into groups of eight and led to a large room that smelled of disinfectant and soap. Dr. Emily Yamamoto stepped forward. A Japanese American woman in a crisp medical uniform and her very presence was itself a shock. A Japanese face speaking with American authority. A woman wearing an American officer’s insignia.

a person who moved between both worlds as if such a thing were possible, as if loyalty could exist without betraying one side or the other. Dr. Yamamoto explained in perfect Japanese what would happen next. The lice infestation was severe. They would need to cut the women’s hair. For some, complete shaving would be necessary. The room fell silent.

Every woman understood what this meant. In Japanese culture, a woman’s hair was sacred. A shaved head meant shame, punishment, the mark of an adulteress or a criminal. Yoko touched her matted hair protectively, her fingers finding the rough tangles, the scabs beneath, the lice that scattered at her touch. So this was the cruelty.

This was how the Americans would break them, not through violence, but through humiliation. But then Lieutenant Williams entered, carrying a wicker basket. She began removing items one by one, placing them on a metal table where everyone could see. Soft white towels, bars of soap and paper wrappers, small bottles that smelled like medicine and flowers, and then something that made several women gasp.

Cotton robes, white and clean, folded neatly like gifts. William spoke through Dr. Yamamoto. Her voice apologetic. These are for you to wear afterward. We have undergarments, too. We want you to be comfortable. We want you to feel human again. The first woman sat in the chair. Her name was Hana, a former school teacher from Osaka.

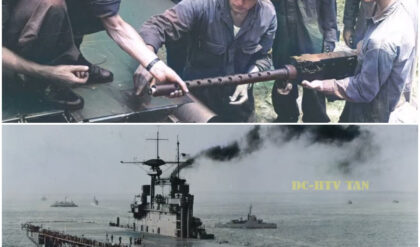

And she trembled so violently the chair shook beneath her. The American nurse moved slowly, explaining each action through the transl before she did it, showing Hana the electric clippers, demonstrating how they worked, asking permission before she touched Hana’s hair. The clippers hummed to life. The first clump of matted hair fell to the white tile floor.

With it fell dozens of lice, visible, scattering, desperate. Hannah let out a sob that came from somewhere deep and broken. The American nurse paused immediately. She placed one hand on Hannah’s shoulder and waited, not impatiently, not with irritation, just waited until the trembling subsided, until Hannah could breathe again, until she nodded for the nurse to continue.

When the clippers nicked the scalp and a small bead of blood appeared, the nurse stopped completely. She cleaned the cut with gentle pressure. She applied a bandage. She apologized through the transl. She apologized for causing pain. The enemy had apologized. Yoko watched from across the room, her turn approaching with each woman who sat in the chair.

She had prepared herself for rough hands and mocking laughter. She had steeled herself to endure whatever came. But what she saw instead was care, methodical, professional care. Each nurse worked as if the woman in her chair mattered, as if her dignity was worth preserving, even in this moment of profound loss.

When Yoko’s turn came, she sat with eyes closed and hands clenched in her lap. She felt gentle fingers assessing the damage to her scalp. Felt the nurse paused to examine the worst of the bleeding sores. “It’s very bad,” the nurse said in English. And Yoko understood enough to grasp the meaning. “We’ll need to take it all. I’m sorry.” The clippers touched her scalp.

The vibration traveled through her skull. The first lock of hair fell away, black and matted and crawling with tiny horrors. And with it something broke inside her, not from shame, from relief. The lice had been her constant torment for 18 months. every waking moment, every restless night.

Crawling, biting, breeding in the tangles she couldn’t comb out, driving her to scratch until her scalp bled and the blood dried and the lice bred in the scabs. She had dreamed of being clean, had fantasized about it the way starving people fantasize about food. And now, with each pass of the Clippers, the nightmare was ending.

The nurse worked methodically, carefully, as if Yoko’s comfort mattered more than efficiency. When a tangle proved stubborn, she didn’t yank. She applied something from a bottle that smelled like kerosene and flowers. She waited for it to work. She tried again with gentler pressure. When she accidentally pulled too hard and Yoko flinched, the nurse stopped.

She murmured something soft in English. She continued more slowly, more carefully, her fingers light against Yoko’s damaged skin. Yoko opened her eyes and looked up. The American woman had blue eyes, a color Yoko had rarely seen, the color of the propaganda demons. But those eyes held no hatred, no contempt, only concentration and………next