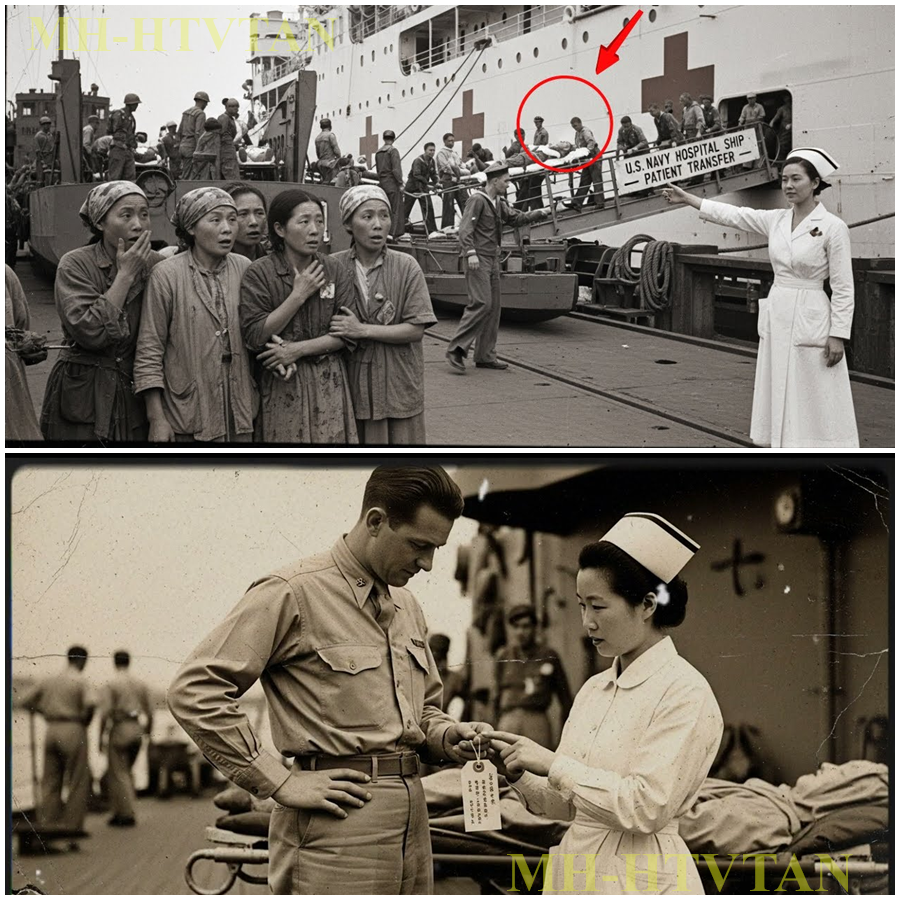

October 15th, 1945. Port of Tanipog, Saipan. The world was a dizzying blur of gray steel and blinding white enamel. Kiko Tanaka, formerly a nurse with the Imperial Army’s 43rd Division, felt her stomach lurch as the wire basket swung out over the dark, oily water.

She was suspended 30 ft in the air, trapped inside a rigid metal cage, a Stokes llitter hoisted by a winch that groaned with the rhythmic mechanical indifference of American industry. Below her, the diesel fumes of the landing craft LCT were suffocating, mixing with the rot of the harbor. Above the hull of the USS benevolence rose like a man-made cliff face, an expanse of white so pure it hurt her eyes, broken only by the colossal red cross painted on the side.

To her exhausted mind, shaped by months of propaganda, it looked less like a sanctuary and more like a sacrificial altar. Steady on the winch, watch the swing, a voice bellowed from the deck above. the English words sharp and percussive. Ko gripped the wire mesh until her knuckles turned white.

She wasn’t wounded, but she was being lifted with the invalids, a translator for the dying. As the basket cleared the rail, a gust of wind caught them. The litter twisted violently. For a second, she stared directly down into the churn of the propeller wash. This was it, the rumored execution. The Americans didn’t shoot you. They simply dropped you into the sea. Shikari Shiro, she whispered to herself.

Hold on. The basket jerked, then settled with a surprisingly gentle clank onto the deck. A face appeared above the mesh. A young man with a white sailor’s cap and blue eyes that held no hate, only professional urgency. “Welcome aboard, ma’am,” he said, unbuckling the straps.

If you enjoy deep dives into history’s forgotten perspectives, consider subscribing and commenting which country’s history we should explore next. Two weeks earlier, the civilian internment camp, Suzupe. The heat in the Suzupe internment camp was not a temperature. It was a physical weight pressing down on the corrugated tin roofs and the bowed backs of the defeated.

It smelled of coral dust, unwashed bodies, and the cloying sweetness of rotting sugar cane. Kiko Tanaka wiped sweat from her forehead with the back of a grime streaked hand. She knelt beside Mrs. Sato on the dirt floor of the medical tent. “Satosan,” Ko whispered, dipping a rag into a helmet filled with tepid water. “Drink a little.” Mrs.

Sato, a civilian whose leg had been shattered by mortar fire during the invasion, barely opened her eyes. The wound was wrapped in bandages made from torn parachute silk, now stiff with dried fluid. “Is it time?” the older woman rasped, her voice thin as paper. “Are they coming to finish us?” “No,” Ko lied, though her own heart hammered a frantic rhythm against her ribs. “Just a checkup.

” Outside the tent, the camp hummed with the nervous energy of a disturbed hive. The rumors had started at dawn. The American doctors, the tall men with hairy arms and loud voices, had been walking the roads, pointing not at the healthy workers, but at the broken ones, the burdens. In the Imperial Army, the weak were expected to die with dignity to save resources for the fighters.

Ko knew this logic intimately. It was the logic of survival. Now looking at the Americans, she feared their logic was even colder. Efficiency. Why feed mouths that could not work? A cloud of dust heralded the arrival. A US Army truck, a six behemoth painted in olive drab, groan to a halt near the perimeter wire.

Two MPs hopped out, their boots striking the earth with a sound of absolute authority. They wore white gators and polished helmets that caught the brutal sun. “All right, let’s move him out,” one of the Americans shouted. He held a clipboard, a weapon of bureaucracy more terrifying to Ko than a rifle. He didn’t look at the prisoners as people.

He looked at them as inventory. A Ni translator, a Japanese American whose face looked like a brother but whose uniform marked him as an alien, stepped forward. Attention. Those named will assemble for transport. Medical transfer. Do not resist. Medical transfer. The euphemism chilled Ko’s blood. The translator began reading names. Sado Mori Yamamoto.

Mrs. Sato tried to sit up. panic flaring in her cloudy eyes. Ko, don’t let them take me alone. Ko looked at the MPs, then at the helpless woman. She stood up, brushing the dirt from her tattered MP trousers. She was a nurse. She had failed to die for the emperor, but she would not fail her patient.

She walked toward the clipboard, her chin raised, trembling only slightly. I go,” she said in broken English, pointing to the Red Cross brasard, still pinned to her arm. “I, nurse, I go with them.” The MP looked her up and down, chewing gum with an indifference that was almost insulting. He shrugged. “Load them up. Need someone to wipe their faces anyway.

” The world shrank to a twilight box of olive drab canvas and the smell of hot transmission oil. Inside the rear of the GMC CCKW truck, 12 women were packed on wooden bench seats, sliding dangerously with every lurch of the vehicle. The truck didn’t drive so much as it hammered the earth.

The suspension was built for hauling ammunition crates, not shattered human bodies. Every pothole in the coral road sent a shock wave through the frame, eliciting groans from the patients on the floor stretchers. Ko braced her legs against the tailgate, using her own body as a wedge to keep Mrs. Sto from rolling.

“They’re taking us to the cliffs,” a woman whispered from the darkness near the cab. “It was Tanaka, a school teacher who had lost an arm.” “Like at Mpy Point, to throw us over.” “Quiet,” Ko hissed, though the vibration of the engine rattled her own teeth. “It is a hospital,” they said. Hospital. Since when do demons build hospitals for the damned to knock a shot back? Ko had no answer.

The air inside the canvas tunnel was thick with dust and the sour of unwashed wounds. Through the small gap in the front canvas, she could see the back of the driver’s neck. Thick, sunburned, and relaxed. He was smoking a cigarette, the blue smoke drifting back to mix with the exhaust. That casualness was more terrifying than anger.

It implied that transporting dying women was just a job, no different from hauling scrap metal. The truck gears ground down, the engine roaring as they descended a steep grade. Gravity pulled them forward, a collective pile of misery. Then the brakes squealled, metal biting metal, and the beast lurched to a halt. The sudden silence was deafening, broken only by the distant cry of seagulls and the heavy thrum of machinery.

The rear canvas flap was thrown open. Light, blinding, tropical, merciless light flooded the compartment. Ko squinted, shielding her eyes as an MP banged on the tailgate with a baton. Everybody out. Let’s go. Let’s go. Ko scrambled down first to help lift the stretchers.

As her boots hit the ground, the view stole the breath from her lungs. They were at Tanipag Harbor, but the landscape she remembered was gone. The sea was no longer visible. It was paved over with steel. Dozens of gray Liberty ships sat low in the water, their cranes swinging like the arms of giant insects, offloading crates faster than she could count.

Amphibious tractors churned the water and jeeps buzzed like flies along the pier. But it was the ship in the center that froze her blood. It was colossal, painted a white so pristine it looked like a tear in reality against the grimy gray of the harbor. A red cross three stories high was emlazed on its side. It didn’t look like a ship of war. It looked like a temple of the future, floating on the oil sllicked water.

“Move it!” the MP shouted, gesturing toward the water’s edge where a flatbottomed boat waited. Ko gripped the handle of Mrs. Sad’s stretcher. The rumors of the cliffs were wrong. This was something else entirely. They were being fed into a machine.

The gap between the concrete pier and the rusting steel gunnel of the landing craft was only 2 ft wide, but it churned with black oily water. The LCT, repurposed as a harbor ferry, heaved rhythmically on the swell, grinding against the tire bumpers of the dock with a sound like a dying animal screaming, “Watch the timing. Wait for the rise.

” A boatin bellowed from the deck of the craft, his voice barely audible over the coughing roar of the twin diesel engines. The air was blue with exhaust smoke, thick and greasy, coating the back of Ko’s throat. Ko stood at the edge of the pier, gripping the foot of Mrs. Sad’s stretcher. Her palms were slick with sweat. Opposite her, a terrified young girl from the camp held the head. They had to jump.

If they mistimed it, the steel hull would rise up and crush their legs, or worse, they would drop Mrs. Sato into the dark water below. “On three,” Ko shouted in Japanese, trying to pitch her voice below the mechanical den. “One, two,” they lunged. Ko’s boots hit the steel deck of the LCT with a heavy clang.

She stumbled, the wet metal treacherous as ice. The stretcher listed violently to the right. Mrs. Sato let out a low moan of pain as she began to slide toward the edge. Suddenly, a pair of thick haircovered arms shot out from the shadows of the wheelhouse.

Ko gasped and flinched, ducking her head and squeezing her eyes shut, waiting for the blow. She had been taught that American sailors were undisiplined brutes who took pleasure in cruelty. She braced for the impact of a fist or a boot. It never came. Instead, she felt the weight of the stretcher lighten. She opened her eyes.

An American sailor, shirtless and glistening with grime, had caught the frame of the litter. He wasn’t looking at her. He was looking at the patient. His face was a mask of concentration as he expertly leveled the load, absorbing the roll of the boat with his knees. Easy, Mac, he grunted to no one in particular.

He nodded at Ko, a sharp upward jerk of the chin, and pointed to a spot near the bulkhead. Stow it there. Keep the gang way clear. Ko stared at him, her breath caught in her throat. He didn’t smile, but there was no malice in his eyes, only a bored professional competence. He turned his back on her immediately to grab the next stretcher. He had saved her from dropping the patient. The realization sat uncomfortably in her stomach.

It was easier to hate a monster than to understand a man who did his job. She dragged Mrs. S’s stretcher to the indicated spot, huddling against the cold steel wall. The ramp slammed shut, and the diesel engines throttled up to a deafening scream. The LCT shuttered and pulled away from the pier, turning its blunt nose toward the open harbor.

Ahead of them, the white hospital ship grew larger, blocking out the sun. It was no longer a ship. It was a white wall of iron, 500 ft long, casting a long, cool shadow over their small, trembling boat. The LCT drifted into the lee of the hospital ship, and the sun vanished.

They were floating in an artificial twilight created by the sheer vertical expanse of the USS Benevolence. To Ko, looking up from the waterline, the ship did not look like a vessel. It looked like a white cliff face that had severed itself from the land and drifted out to sea. The hull was an endless wall of riveted steel painted a glossy, blinding white that seemed to repel the grime of the war.

Dominating the center of this steel cliff was a red cross. It was three stories tall, a geometric scream of crimson against the white. In the Geneva Convention manuals she had studied briefly, this symbol meant neutrality and mercy. But here, looming over their tiny diesel choked boat, it felt like a target marker or a warning. The LCT bobbed helplessly in the ship’s wake.

The women on the stretchers fell silent. The immensity of the American machine silenced even their pain. They were ants floating beside a whale. “Stand by for transfer,” a voice crackled from a loudspeaker high above. A mechanical wine pierced the air, sharp and grinding. Far above, a boom crane swung out from the upper deck. Cables unspooled, whistling as they cut through the humid air. “What is that?” Mrs.

Sad whispered, her hand clutching Ko’s wrist with a grip of iron. What are they dropping? Ko watched as the objects descended. They weren’t stretchers. They were rigid baskets made of heavy wire mesh and tubular steel shaped like sarcophagy. Stokes litters. To Ko’s exhausted mind, they didn’t look like medical devices. They looked like cages.

the kind used to trap wild boores in the mountains of Okinawa or lobster pots used by fishermen. The baskets hit the deck of the LCT with a heavy metallic clatter. “Load them up!” the boats on the LCT yelled, gesturing impatiently. “One per basket. Strap them tight. We got a sea running.

” Ko stared at the wire cage. They wanted her to strap these terrified, broken women into metal cocoons and dangle them over the ocean. It felt like a final humiliation. You do not cure people in cages. You transport livestock. Tanakasan, Mrs. S whimpered, trying to pull away. Don’t put me in the box, please.

Ko swallowed the bile rising in her throat. She looked at the American sailors waiting by the winch cables. They were indifferent, checking their watches. If she hesitated, they would do it themselves, and they would not be gentle. “It is for safety,” Satosan, Kiko said, forcing her voice to be steady, slipping back into the role of the officer she once was.

She knelt by the basket, unbuckling the heavy canvas straps. “It is the only way up. Close your eyes. I will be right behind you.” She began to tighten the straps across Mrs. S’s chest, effectively binding her prisoner to the machine. Hoist away. The command was followed by the shrill blast of a boatman’s mate’s whistle.

The cable snapped taut, vibrating with the immense tension of the load. Mrs. Sad’s wire basket jerked upward, clearing the deck of the LCT by inches before ascending into the empty air. Ko craned her neck, shielding her eyes against the glare of the white hull.

Two sailors on the LCT held tag lines, heavy manila ropes attached to the bottom of the basket to keep it from spinning in the wind. They played the lines out carefully, their muscles coiling like snakes under their wet dungarees. For the first 20 ft, the ascent was smooth. Then a gust of wind channeled between the ship and the boat hit the basket like a physical blow. The litter twisted violently.

It began to pendulum, swinging in a wide arc toward the solid steel wall of the benevolence. Mrs. Sato screamed a thin high-pitched sound that was swallowed by the wind. Hold her. Check the swing. The chief petty officer roared. The sailor nearest Ko, a red head with a face full of freckles, planted his feet on the slick steel deck.

He hauled back on his tagline with everything he had. But the wet deck betrayed him. His boot slipped on a patch of oil. He went down hard on one knee, losing his footing. The heavy rope began to tear through his grip, sizzling as it picked up speed. If he let go, Mrs. Sato would smash into the rivets of the hull. He didn’t let go.

Ko watched in frozen horror as the sailor, instead of releasing the burning line, whipped it around his forearm to create a friction break. The rope bit deep into his flesh. She saw the skin tear, saw the raw red line appear instantly as the coarse hemp burned him. He gritted his teeth, his face turning crimson with effort, but he anchored the line with his body weight.

The basket jerked to a halt just inches from the white steel. It stabilized, swaying gently now. “Clear! Take her up!” the sailor gasped, unwinding the rope from his bleeding arm. He didn’t look at his wound. He looked up at the basket, checking the patient. Ko stared at the sailor’s arm. A strip of skin was peeled back. Weeping blood mixed with grease.

Why? The question hammered in her skull. Why bleed for us? Why burn your flesh for a broken woman of the enemy? The Americans were supposed to be Kitiku beasts. Beasts did not sacrifice their bodies for their prey. The dissonance made her dizzy more than the rocking of the boat.

The map of her world, drawn in the ink of propaganda, was dissolving. The empty basket came back down a minute later. The sailor, still nursing his arm, looked at Ko. “You’re next, ma’am,” he said, his voice tight with pain, but steady. “Step in.” Ko’s basket touched the teak deck of the USS Benevolence with a solid thump. The wire mesh was instantly unbuckled by efficient hands.

As she was helped out, the world tilted, not from the waves, but from the sensory overload. The quarter deck was a hive of controlled chaos. It didn’t smell like the ocean anymore. It smelled of rubbing alcohol, fresh paint, and the sharp chemical tang of DDT. Everything was aggressively clean.

The sailors wore blinding white uniforms that seemed impossible to keep spotless in a war zone. Line them up. Walking wounded over here. Litter cases to the bulkheads. A petty officer shouted, his voice cutting through the wind. The women from Suzupe huddled together like frightened sheep clutching their rags. A corman approached them with a metal canister that looked ominously like a weapon. “Dusting,” he said flatly.

Before anyone could scream, he pumped a plunger, blasting a cloud of white powder down the back of Ko’s neck and into her hair. DDT. Mrs. Sato, lying on her stretcher nearby, began to weep, thinking it was poison. It is just for lice, Satosan, Ko said, coughing as the powder settled on her skin. It is hygiene.

A tall American officer, a lieutenant commander with a stethoscope around his neck, was moving down the line of stretchers, flipping through attached notes, and tying manila tags to the patients clothing. He stopped at a young girl, my who was clutching her stomach. He reached for her abdomen, his fingers probing deep. My screamed, “Acendicitis,” the doctor muttered to his scribe. Prep O3. No.

Ko stepped forward, breaking the invisible barrier between prisoner and captor. Her heart hammered, but her training took over. Not appendix, please. She has dysentery. Severe cramping. No surgery. The deck went silent. The MP standing guard took a step toward Ko, his hand resting on his baton. A prisoner did not correct an officer.

The lieutenant commander held up a hand to stop the guard. He looked at Ko, really looked at her for the first time. He didn’t see a dirty enemy. He saw the way she stood, the way her eyes tracked the patients symptoms. He turned back to my palpating the stomach again, gentler this time. He checked the hydration of her gums.

He stood up and nodded. “You’re right,” he said, his voice neutral. Dehydration, cramping, good catch. He scratched out the note on the tag and wrote, “Gastrointeritis.” Then he looked at Ko. “You a nurse?” “Yes,” Ko whispered. “Imperial Army.” “Stick with this group,” the doctor ordered, pointing his pen at her. “We need the histories.

Don’t let them get separated.” He didn’t bow, and he didn’t smile. But he had just granted her a rank she thought she had lost forever. She was no longer just a number to be guarded. She was a resource to be used. “Move them to the elevator,” the boatsman called out. The group was marshaled toward a large square platform in the deck.

The aircraft elevator, now used for mass casualties. The elevator platform was large enough to hold a jeep, but with 20 people and six litters crowded onto it, the air felt thin. The heavy steel safety gates rattled shut with a final jail cell clang. Going down, the operator ined. The floor dropped out from under them. The sudden sensation of falling triggered the break.

They are sealing us in. It was Tanaka, the teacher with the amputated arm. She scrambled up from her sitting position, her eyes wide with a feral terror. It is the gas. Like they said, don’t let the doors close. She lunged toward the metal grate, flailing her remaining arm.

She collided with the MP, clawing at his uniform. The guard, startled, raised his baton reflexively. “Hey, back off. Get back.” Tanakasan. “Stop!” Ko screamed, pushing through the press of bodies. But the panic was contagious. Mrs. Sato began to thrash on her stretcher, her movements tearing at the bandages on her shattered leg.

Fresh blood began to bloom through the white gauze. “She’s ripping her sutures!” A corman yelled, trying to pin Mrs. Sto’s shoulders down. “She’s going to bleed out. I need a seditive.” The elevator groaned, the mechanical hum vibrating through the steel floor plates, amplifying the chaos. The MP raised his baton higher, ready to strike Tanaka to restore order.

“No!” Ko threw herself between the guard and the teacher. She turned to the corman, her eyes locking onto his. Give it to me. She knows me. She will fight you. The corman hesitated. He looked at the frantic woman, then at Ko. In that split second, the war hung in the balance. Giving a prisoner a needle was against protocol. It was a weapon.

He reached into his webbing and pulled out a small squashed metal tube with a needle attached. A morphine curette. He didn’t administer it. He handed it to Ko. Do it. He snapped. Half dose. Ko grabbed the tube. She felt the cold metal against her sweating palm. She broke the seal with the wire pin just as she had been trained and turned to Mrs. Sato.

Satosan, look at me. Ko’s voice was sharp, the voice of a head nurse, not a prisoner. It is medicine. Only medicine. Mrs. Sato froze, her eyes finding Ko’s face. Ko jammed the needle into the woman’s thigh and squeezed the collapsible tube. “Sleep!” Ko whispered. “It is over!” Mrs.

Sato’s thrashing slowed, her breathing hitched, then deepened. The tension in the elevator broke as the drug took hold. Tanaka, seeing her friend calm down, slumped against the wall, weeping silently. The MP lowered his baton, exhaling a long breath. The corman looked at Ko. He gave a single curt nod. It wasn’t friendly, but it was respectful.

With a pneumatic hiss, the elevator jolted to a halt. The heavy gates slid open. The elevator gates opened and the heat of Saipan vanished. It was replaced by a sensation Ko had forgotten existed. Cool, dry air. The USS Benevolence was airond conditioned.

To women who had spent months rotting in the humid filth of the jungle and the dusty camp, the sudden drop in temperature felt like walking onto another planet. They were wheeled intoward sea. It was a cathedral of stainless steel and white enamel. There were no flies. There was no smell of gang green or excrement. The air smelled faintly of floor wax, rubbing alcohol, and brewing coffee. Ko walked beside Mrs. S’s stretcher, her boots squeaking on the polished lenolium. She felt dirty.

Her presence seemed to stain the pristine room. Nurses in crisp white uniforms. Women with curled hair and bright red lipstick moved with efficient grace. They didn’t scream orders. They whispered. They transferred the Japanese patients onto beds with mattresses so thick they looked like clouds.

Sheets impossibly white and smelling of laundry soap were drawn up over the women’s soores. This is a trick, Mrs. Sato murmured, touching the sheet with a trembling hand. They make us comfortable before they kill us. No, Ko said, though her own voice lacked conviction. She watched a nurse adjust a pillow for Tanaka. The nurse smiled, a genuine tired smile, and patted Tanaka’s shoulder.

Then the metal carts arrived. The smell hit Ko first, not the smell of rice or watery fish soup, but the rich, heavy scent of meat and animal fat. A young sailor placed a stainless steel tray on the bedside table next to Ko. She stared at it. There was a scoop of mashed potatoes swimming in brown gravy. There were green beans that were actually green, not gray.

There was a thick slice of meatloaf, and in a small corner section of the tray, a cup of orange gelatin that wobbled in the light. It was more calories on one tray than she had eaten in three days at the camp. Eat up,” the sailor said, moving to the next bed. Ko picked up a heavy metal spoon. It wasn’t tin. It was solid silver plate stamped with USN. She took a bite of the potatoes.

The salt and fat exploded on her tongue so intense it almost hurt. Tears pricricked her eyes, not from gratitude, but from a crushing sense of defeat. She looked around the ward. The other women were eating ravenously, weeping as they shoveled the food into their mouths. This was the true weapon of the Americans. It wasn’t the flamethrower or the B29.

It was this, the logistics, the ability to build a floating city of ice and steel, bring it across the ocean, and feed the enemy better than the emperor fed his own imperial guard. There was no fighting this. The war had been lost before the first shot was fired. Ko sat on the edge of an empty bed she had been assigned.

She felt the softness of the mattress give way under her weight. She thought back to the wire basket swinging over the water, the terror of the drop. She had been lifted out of the grave and placed in heaven, but it was a heaven built by the people she was sworn to hate. She lay back, the cool pillow cradling her head. The hum of the ventilation system was a steady mechanical lullabi.

For the first time in 2 years, she did not listen for the sound of airplanes. “The war is over,” she whispered to the white ceiling. And finally she slept.