March 24th, 1945, 22,000 feet above the German countryside near Castle, Oberlutinant France Stigler sat in the cockpit of his Messersmid BF 109, and he knew he was about to die. The fuel gauge showed empty. The engines sputtered, coughed, fighting for every last drop of aviation fuel that was not there.

Below him stretched 50 mi of territory controlled by the Americans. Behind him, his own airfield was unreachable, and all around him the sky belonged to the enemy. Fronz’s hands trembled on the control stick. Not from the cold, though. It was brutally cold at this altitude. He trembled because he knew what came next. He had heard the stories.

Every Luftwaffa pilot had American fighters did not just shoot you down. They strafed you in your parachute. They circled overhead while you dangled helplessly. Easy target practice. The Americans were barbarians, his commander said. They showed no mercy to down German pilots. If you bailed out over Allied territory, you were as good as dead.

Fron looked down at the patchwork of fields and villages below. Somewhere down there were American troops, American tanks, American soldiers who had been fighting their way across Europe for months. Men who had seen their friends die. Men who had every reason to hate them. The engine coughed again and this time it did not recover.

The propeller windmilled uselessly in the slipstream. Dead stick. No power. He was gliding now. Nothing but a 30foot wingspan and gravity. He could see an American airfield ahead. A captured Lufafa base now bristling with American aircraft. He had maybe 2 minutes before he would have to bail out or attempt a forced landing. Fron thought about his family in Bavaria.

His mother, his younger sister. They would receive a telegram missing in action. They would never know what happened to him, whether he burned alive in the cockpit or was shot while hanging from his parachute or was beaten to death by angry American soldiers on the ground. Then he saw them.

Two silver specks in his mirror, closing fast. P-51 Mustangs, American fighters, the most lethal aircraft in the European theater. Fron’s mouth went dry. This was it. They would shoot him out of the sky before he even had a chance to bail out. At least it would be quick. But what happened next would change everything he thought he knew about Americans.

The lead Mustang pulled alongside Fron’s dying Messor Schmidt. Close. Dangerously close. Maybe 50 ft off his wing tip. Fron could see the pilot’s face clearly through the canopy. an American, young, probably his own age, mid20s. The pilot was not reaching for his gun trigger. He was looking at Fron, making eye contact. Then the American did something Fron could not comprehend.

He pointed down, not aggressively, almost helpfully, pointing toward the airfield below. Fron stared. Was this a trick? Some kind of cruel game before they shot him down? The second Mustang took position on Fran’s other wing. Now he had American fighters on both sides, boxing him in. His Messor Schmidt was gliding down through 18,000 ft, losing altitude steadily.

He had no power, no options, no way to fight or flee. The lead American pilot pointed down again, more insistently this time. Then he made a gesture, palms down, pushing motion. Slow down. Land. Fron’s mind reeled. They were helping him, escorting him to an emergency landing. That could not be right. Nothing in his training, nothing he had been told about the Americans prepared him for this.

His altimeter unwound through 15,000 ft. The airfield was directly ahead now. He could see the runways clearly. American aircraft parked in neat rows. Crews working on the flight line. If he tried to land there, he would be captured. a prisoner of war at the mercy of the Americans. Every propaganda film he had ever watched flashed through his mind.

Stories of torture, of summary executions, of prisoners worked to death in labor camps. His commanding officer had told them it was better to die in combat than to surrender to the Americans. But he was out of options. The ground was coming up fast. The American pilots stayed with him, one on each wing, escorting him down like he was one of their own, through 10,000 ft.

8,000 5,000. Fronz’s hands were slick with sweat inside his leather gloves, his heart hammered against his ribs. He kept waiting for the burst of machine gun fire that would tear his aircraft apart. It never came. At 3,000 ft, the lead American pilot rocked his wings a signal.

Then he peeled off, giving Fron room to maneuver for landing. The second Mustang stayed with him, shephering him toward the runway like a border collie guiding a lost sheep. Fron lowered his landing gear manually. The hydraulics were useless without engine power. The wheels locked down with a reassuring thunk. He lined up on the runway, fighting the controls of the dead aircraft, using every bit of his training to stretch the glide.

The American fighter stayed with him until he was 50 ft off the runway, then pulled up and away. Fron’s wheels touched concrete. The Messor Schmidt bounced once, settled, rolled. He had no brakes, no power for the hydraulic system. The aircraft rolled and rolled, finally shuttering to a stop at the far end of the runway.

For a moment, France just sat there, hands still gripping the control stick, breathing hard. Then he saw the jeeps racing toward him. American soldiers. This was it, the moment of capture. He thought about reaching for his sidearm, making a last stand. Dying as a German officer should die, but something stopped him. Those American pilots had just saved his life.

They could have shot him down easily. Instead, they had helped him land safely. Fron unbuckled his harness, pushed open the canopy, and raised his hands. The first American soldier to reach Fron’s aircraft was a sergeant named Robert Hayes from Oklahoma. He climbed up on the wing, pistol drawn, but pointed down, not at Fron.

Out, Hayes said in English. Then, surprisingly in broken German, “Rouse Langom.” Slowly, Fron climbed out of the cockpit, legs shaking from adrenaline and exhaustion. He had been flying for 3 hours. His flight suit was soaked with sweat despite the cold. He stood on the wing, hands raised, waiting for what? A rifle butt to the face. Rough handling.

Immediate interrogation. Hayes holstered his pistol. He reached out and steadied Fron as he climbed down from the wing. “Easy there, buddy,” Hayes said. “You okay? Verlet injured.” Fron stared at him. The American sergeant was checking if he was hurt with genuine concern in his voice.

Nine, Fron managed, not injured. Good. Come on then. Hayes gestured toward the jeep. Not roughly, almost casually. Like Fron was a visiting pilot who had made an emergency landing. Not an enemy combatant who had been bombing Allied positions for years. In the jeep, Fron sat between two American soldiers. Neither pointed a weapon at him.

They just sat there, human beings in olive drab uniforms, smelling of cigarette smoke and army coffee. One of them offered Fron a canteen water. Fron hesitated, then took it. His throat was raw with thirst. The water was cold and clean and possibly the best thing he had ever tasted. “Danky,” he said quietly. The soldier grinned. “You are welcome, pal.

” At the base operations building, they brought Fron inside into warmth out of the March cold. An intelligence officer was waiting. Captain James Mitchell, a former college professor from Massachusetts who spoke fluent German. Sit down, Mitchell said in German, pointing to a chair. Not a hard wooden chair in an interrogation room.

A comfortable office chair. There was coffee on the desk. Real coffee. And the smell of it made Fran’s head spin. You want some?” Mitchell asked, already pouring a cup. Fron nodded, not trusting himself to speak. Mitchell handed him the coffee hot black with two sugar cubes on the saucer. Sugar. Real sugar. France had not seen real sugar in months.

Germany was starving, rationing everything. And here the Americans were giving sugar to a prisoner. Those were good pilots who brought you in, Mitchell said conversationally, sitting down across from Fron. Captain Joe Henderson and Lieutenant Charlie Brennan, 357th Fighter Group. They saw your engine was out and figured you might want to live through the day. Fron sipped the coffee.

It burned his tongue. He did not care. Why? The word came out before he could stop it. Mitchell looked at him curiously. Why? What? Why did they not shoot me down? Why did they help me? Mitchell seemed genuinely puzzled by the question. Because you were defenseless. What kind of men do you think we are? Over the next hour, Fran’s entire world view began to crumble.

They took him to the P holding area. Not a cage or a cell, but a converted barracks building with bunks, blankets, and a working stove. There were a dozen other German prisoners there, all recently captured, all with the same stunned expression Fron felt on his own face. An American medic examined him anyway, despite Fran’s insistence he was not injured, the medic checked his blood pressure, looked in his eyes, listened to his heart.

“You are dehydrated,” the medic said through an interpreter. “And you have got some frost bites starting on your fingers. We will get you fixed up.” They gave him ointment for his hands, a wool blanket, a package of American Krations, canned meat, crackers, chocolate, cigarettes. The chocolate was dark and rich and tasted like childhood, like before the war.

Fron ate it slowly, savoring every bite. That evening, Captain Henderson, the pilot who had escorted Fron down, came to visit. He brought cigarettes and a thermos of hot soup. “Thought you might be hungry,” Henderson said through the interpreter. That was some nice flying, by the way. Dead stick landing in a Mi 109 on an unfamiliar runway. Impressive.

Fron did not know what to say. This American pilot was complimenting his flying skills. They had been trying to kill each other for years, and now Henderson was treating him like a colleague who had had some bad luck. Henderson pulled out a photograph from his wallet. A woman and two small children. “My wife Betty and my kids,” he said.

“Donna is five. Little Joe just turned three. You’ve got family. Fron nodded slowly. My mother, my sister. They will be glad to know you made it down safe, Henderson said. Red Cross will notify them. You are a P. Better than missing an action, right? They sat in silence for a moment. Two fighter pilots on opposite sides of a war looking at family photos in the dim light of a P barracks.

Listen, Henderson said finally. I know what they told you about us. Probably said we would torture you, shoot prisoners, all that garbage. But that is not who we are. You are going to be treated according to the Geneva Convention. You will get medical care, food, mail privileges, and when this war is over, and it will be over soon, you will go home.

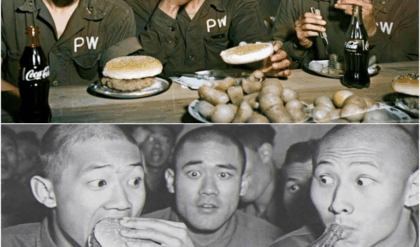

France felt something break inside him. Not break, crack open, like ice thawing. In Germany, he said carefully in broken English. They tell us Americans are animals. Henderson laughed, but not unkindly. Yeah, well, they told us you guys eat babies for breakfast. Propaganda is a hell of a thing, is it not? Over the next 3 weeks at the temporary P camp, Fron witnessed something that challenged everything he thought he knew about America and Americans.

The food was adequate. Not luxurious, but consistent. K rations, powdered eggs, canned meat. The same food American soldiers ate. When the Red Cross parcels arrived, prisoners got first pick. Chocolate, cigarettes, coffee, soap, little luxuries that felt like miracles to men who had been living on war rations for years.

Medical care was provided without hesitation. One of the German prisoners, a young pilot named Verer, had been shot in the leg before capture. The American doctors treated him the same way they treated their own wounded. Sulfa drugs, clean bandages, surgery to remove the bullet. Verer walked with a limp, but he walked.

In a German P camp, he probably would have lost the leg. Fron watched the American guards carefully, waiting for the cruelty to emerge. It never did. They were professional, sometimes bored, occasionally friendly. One guard, a kid from Nebraska named Tommy, taught Fron’s American baseball terms. Fron taught Tommy some German curse words.

They laughed together. The prisoners were allowed to write letters home censored, but aloud. The Red Cross facilitated it. Fron wrote to his mother telling her he was alive, uninjured, and being treated well. He did not know if she would believe him. France began to understand something fundamental.

The Americans were not being kind out of weakness or naivity. They were being decent because they believed in rules in the Geneva Convention in treating prisoners humanely even when their own soldiers were dying on the front lines. It was not soft. It was strong. It took strength to treat your enemies with dignity.

One afternoon in early April, France was sitting outside the barracks. They were allowed to move around the compound freely when he heard music. American music. Someone had set up a radio and Glenn Miller’s orchestra was playing in the mood. France found himself tapping his foot. He had loved swing music before the war, before it was banned as degenerate American culture. One of the guards noticed.

You like swing? The guard asked. Bronze nodded. Before the war, I listened to it. No kidding. Hold on. The guard disappeared and came back with a record player and a small stack of 78s. Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Arty Shaw. He set it up in the barracks common room. There you go, the guard said. Enjoy. That night, German PS and American guards sat in the same room listening to jazz, tapping their feet to the same rhythm. The war had not ended.

Men were still dying. But in that moment, they were just people who liked music. Another incident, a new prisoner arrived, a Luftwafa pilot named Klouse, who had been badly burned when his plane was hit. His hands were wrapped in bandages, his face scarred. He was bitter, angry, still full of Nazi propaganda.

“They will kill us all eventually,” Klouse said darkly in German. “They are just fattening us up first.” Fron shook his head. “No, they will not. They are not like that. You have been brainwashed. I have been treated like a human being, Fran corrected. Maybe for the first time in 5 years. Klouse did not believe him. Not until the American doctor spent weeks treating his burns, changing his bandages daily, giving him morphine for the pain.

Not until an American nurse sat with him during the worst nights when the pain was unbearable, just talking to him in broken German to distract him. Klaus’s hatred crumbled slowly, like a fortress undermined from within. Perhaps the most powerful moment came 3 days before the German surrender. Captain Mitchell, the intelligence officer, gathered the PS together.

The war is almost over, he said in German. You will be going home soon, but I want you to understand something. When you get home, Germany is going to need rebuilding. It is going to need men who understand that the Nazi way was wrong, who can help build something better. I hope you will be those men.” Fron realized then that the Americans were not just winning the war.

They were thinking about the peace, about what came after, about rebuilding their enemies into allies. It was a longer vision than any German general had ever shown. The treatment France received was not accidental. It was not even exceptional. It was American military policy flowing from the top down. General Eisenhower had made it clear PS would be treated according to the Geneva Convention, period.

Not because German P camps did the same. They often did not, but because Americans believed in a code that transcended the immediate brutality of war. This was not naivity. It was strategy. American leadership understood that how you treat defeated enemies determines what kind of peace you can build.

Every well-treated German P was a potential ally in the reconstruction. Every act of American decency was a counterweight to Nazi propaganda. The numbers tell the story of the approximately 380,000 German PS held in the United States during World War II. The survival rate was over 99%. In German P camps holding Soviet prisoners, the survival rate was around 40%.

In Japanese P camps, it was even worse. This was not because Americans were soft. American soldiers died liberating Europe. They saw the concentration camps. They had every reason to hate, but they followed a different code. It came from American culture, the belief that even enemies have rights, that the rules apply even in war, that how you fight matters as much as whether you win.

France kept a diary during his captivity. It is preserved now in a German military archive. The entries chart his transformation. March 24th. Captured by Americans, expected death. Received coffee and blankets instead. cannot understand this. March 30th. The guards treat us like soldiers, not animals. One shared his cigarettes with me. His name is Tommy.

He has a farm in Nebraska. April 10th. We listen to American music tonight. I had forgotten what it felt like to simply be young, to enjoy something beautiful. The war seems very far away. April 28th. Germany has surrendered. We will go home soon. I do not know what I will find there, but I know now that everything they told us about the Americans was a lie.

They are not monsters. They are men who believe in something larger than themselves. Decades later, in interviews, Fron would say, “Those American pilots saved my life twice. Once when they escorted me down and once when they showed me that not all of humanity had been consumed by the war.

They gave me hope that the world could be better.” He was not alone. Thousands of German PS came home with similar stories. In the years after the war, they became voices for reconciliation, for democracy, for building bridges between former enemies. Between 1943 and 1945, American forces captured approximately 3.8 million German soldiers.

The vast majority were treated according to Geneva Convention standards. P camps in the United States even offered educational programs. German prisoners could take classes, learn trades, prepare for life after the war. Compare this to the Eastern Front, where Soviet and German forces fought with apocalyptic brutality, or the Pacific theater, where surrender was often not an option on either side.

The difference was not just moral, it was strategic. By 1946, the United States was already thinking about the Cold War, about building Western Europe into a bull work against Soviet expansion. Germany, West Germany, needed to be an ally, not a defeated enemy, nursing grievances. Every German P who came home saying, “The Americans treated me fairly,” was a brick in that foundation.

Fran Stigler was repatriated to Germany in August 1945. He found his mother and sister alive in Bavaria, living in a half-destroyed house but alive. His father had died on the Eastern front. His hometown was rubble. He used his skills as a pilot to work for a commercial airline in the 1950s flying for Lufansza as Germany rebuilt.

He never forgot those three weeks as a P or the American pilots who had saved his life. In 1961, Fron immigrated to Canada. He became a successful businessman. He raised a family. He lived a long peaceful life. But he never stopped thinking about that moment at 22,000 ft when the American Mustangs pulled alongside his dying aircraft.

He tried for years to find Captain Joe Henderson, the pilot who had escorted him down. He wrote letters to American veteran organizations, searching. Finally, in 1989, they connected. Henderson was retired, living in Florida. They arranged to meet. When Fran saw Henderson for the first time in 44 years, he wept. Two old men, former enemies, embracing in an airport terminal. “Thank you,” Fran said.

“Thank you for giving me my life.” Henderson, characteristically modest, just shrugged. “It was the right thing to do.” They remained friends until Henderson’s death in 2001. Fran spoke at his funeral, telling the story of the day an enemy became a wingman, a captor became a savior, and propaganda crumbled in the face of simple human decency.

France’s story was one of thousands, but the cumulative effect was profound. By treating PS humanely, America did not just win the war, it won the peace. The Marshall Plan, which rebuilt Western Europe, only worked because Germans were willing to accept American help. And they were willing because their experience with Americans, even as enemies, had shown them that America could be trusted.

West Germany became a crucial cold war ally, a democracy, an economic powerhouse, a partner, not a defeated foe, nursing resentment. Japan followed a similar path. Italy too. The Axis powers of 1945 became the democratic allies of 1955. That transformation did not happen automatically. It happened because American policy from the infantry squad level to the Pentagon emphasized treating enemies with a baseline of human dignity.

It was strategic brilliance disguised as simple decency. In a 1995 interview, France reflected on what that experience taught him. I learned that propaganda is a poison. Both sides told lies about each other. But the difference was when I met Americans face to face, their actions contradicted their propaganda. They showed me through their behavior that human beings could choose to be decent even in the midst of terrible war.

That choice, that is what separates civilization from barbarism. Fran’s children and grandchildren grew up hearing the story. His grandson became a German Air Force pilot and later served alongside American pilots in NATO exercises. The cycle had come full circle. Enemies to capttors to allies to partners.

Before his death in 2008, Fron returned to the airfield in Germany where he had made that emergency landing. It was a civilian airport now peaceful. He stood on the runway and remembered that March day in 1945 when he thought his life was over. I died that day, he said quietly. The man who believed all the lies, who hated without knowing why he died.

And I was reborn as someone who understood that our common humanity is stronger than our temporary enmities. France Stigler’s story is not just history. It is a lesson about the long-term power of treating enemies with dignity. Think about it. Those American pilots had every reason to shoot Fr down.

They had lost friends to the Luftwaffa. They were in the middle of a brutal war. But they chose a different path. They chose to see a defenseless pilot, not a Nazi enemy. They chose to help him land safely before capturing him. That choice rippled outward. Fron became a voice for reconciliation. He raised children who grew up believing in German American friendship.

His story influenced how people thought about former enemies. Multiply that by thousands. Every German P who came home with a story of American fairness, of medical care, of simple respect. Each one was a seed planted for the post-war peace. This is what separates sustainable victory from temporary domination.

You can defeat enemies through force. But you can only build lasting peace by showing them a better way. The Americans understood this instinctively. It was not written in some grand strategy document. It flowed from American culture from the belief that all people have certain rights, that rules matter, that how you treat people in their most vulnerable moments defines who you are.

We live in a world of deep divisions, political, cultural, international. It is easy to dehumanize the other side, to reduce complex people to simple enemies. Fronz’s story reminds us what is possible when we refuse to do that. When we choose to see human beings instead of abstractions, when we treat even our adversaries with a baseline of respect, this does not mean weakness.

The Americans were not weak. They were winning the war. But they understood that strength includes restraint. That true power means following rules even when you do not have to. That building the future matters as much as winning the present. In our current conflicts, military, political, social, we could use more of that long-term thinking, more willingness to see that today’s enemy might be tomorrow’s partner.

More understanding that how we treat people in defeat determines what kind of world we build in victory. Fronz’s grandson, a German Air Force pilot, now flies alongside American pilots in NATO. Former enemies now allies. That is the legacy of treating a powerless enemy pilot with dignity. In March 1945, Fran Stigler climbed into his messmitt on March 24th, 1945, expecting to die as an enemy of America.

He landed as a prisoner, yes, but also as a man who had discovered that propaganda was lies, that enemies could be decent, and that even in the darkest moments of history, human beings could choose to be better than the worst in themselves. He did not find the monsters he had been promised.

He found men who believed that even in war, there are lines you do not cross, rules you follow, standards you maintain. That was not just American military doctrine. That was American character, and it changed the world. Do you have a family story of World War II, of moments when enemies showed unexpected humanity? Share it in the comments.

These stories matter. They remind us what is possible.