You’re just a girl, sweetheart. Go home. The words came with a shove that sent Staff Sergeant Kira Vance stumbling backward into the bar railing. The marine who said it, broad-shouldered, drunk, grinning, had no idea he just put his hands on someone who’d spent the last four years hunting targets in places the Pentagon pretended didn’t exist.

When his fist came next, splitting her lip open, she made a choice that would cost him everything he thought he knew about war. Kira Vance was 28 years old and invisible by design. She sat alone at a corner table in a bar just inside the edge of Camp Pendleton, nursing a ginger ale and trying to remember what normal felt like.

The bar smelled like stale beer and fried food. Country music played too loud from a jukebox that looked older than she was. Marines filled the room, loud and young, fresh from deployment or about to ship out. None of them looked at her twice. That was the point. She’d been back stateside for 6 weeks after a rotation that officially never happened.

Her last posting had been with a joint task force operating out of East Africa, providing intelligence support for operations that would never appear in any briefing. Now she worked a desk job at Marsok headquarters, filing reports and keeping her head down while her paperwork processed for the next rotation.

The bleeding from her lip had mostly stopped, but her jaw still achd where his ring had caught bone. Kira grew up in Duth, Minnesota, the middle daughter of a longhaul trucker and a registered nurse who worked night shifts at the VA hospital.

Her mother brought home stories, not the dramatic ones, but the quiet kind. veterans who couldn’t sleep, who startled at loud noises, who carried weight no one else could see. Kira learned early that service meant sacrifice, and that some people carried more than others. She enlisted at 19, scored high enough on the ASVAB to choose her path, and selected intelligence.

The core sent her to language school in Mterrey, where she picked up Arabic and Pashto, then to Fort Huka for advanced interrogation and intelligence analysis training. She was good at languages because her father had taught her to listen. Really listen to what people weren’t saying. On the road, he’d explained, “You learn to read a situation by watching body language, hearing tone shifts, noticing what changed in a room when certain words got spoken.

” That skill kept her alive through three deployments. Her first rotation took her to Afghanistan as a human intelligence collector attached to a Marine expeditionary unit. She spent 14 months building rapport with local informants, processing intelligence that led to 17 high-v value target captures. The second deployment put her in Iraq during the fight against ISIS, running sources in Mosul while the city burned.

The third brought her to East Africa with a special operations task force she still couldn’t name in official conversation. She worked as a non-operator intelligence staff NCO attached to Marsok, not a raider herself, but essential support running source networks and analysis that enabled direct action missions. She’d been promoted to staff sergeant 2 months before this last rotation ended.

Now she was stateside, waiting, trying to blend back into a world that felt too bright and too loud. The Marine’s name was Corporal Hayes. She didn’t know that yet, but she’d learn it later when the MPs showed up. He’d started with looks from across the bar, the kind that lasted too long that carried assumption rather than interest.

When she didn’t respond, he came over, asked if she was waiting for someone. She said no. He sat down anyway. The conversation went wrong fast. Hayes asked what she did. She said she worked on base. He asked what I was doing. She kept it vague. He pushed. She stayed polite. Then he asked if she was one of those civilian contractors, the kind who got paid too much to do paperwork while real Marines did the bleeding.

She told him she was active duty. He laughed loud enough that two of his buddies at the bar turned to watch. He asked what her MOS was, clearly expecting something administrative. When she said intelligence, he laughed again. Said intelligence. Marines didn’t look like her. said the women he knew in intel were hard, serious, built differently.

She looked too soft, too civilian. One of his friends joined the table, then another. They weren’t aggressive yet, just loud and dismissive in the way drunk men get when they think they found something funny. Hayes told his buddies she claimed to be a marine. They asked where she deployed. She said she couldn’t discuss it.

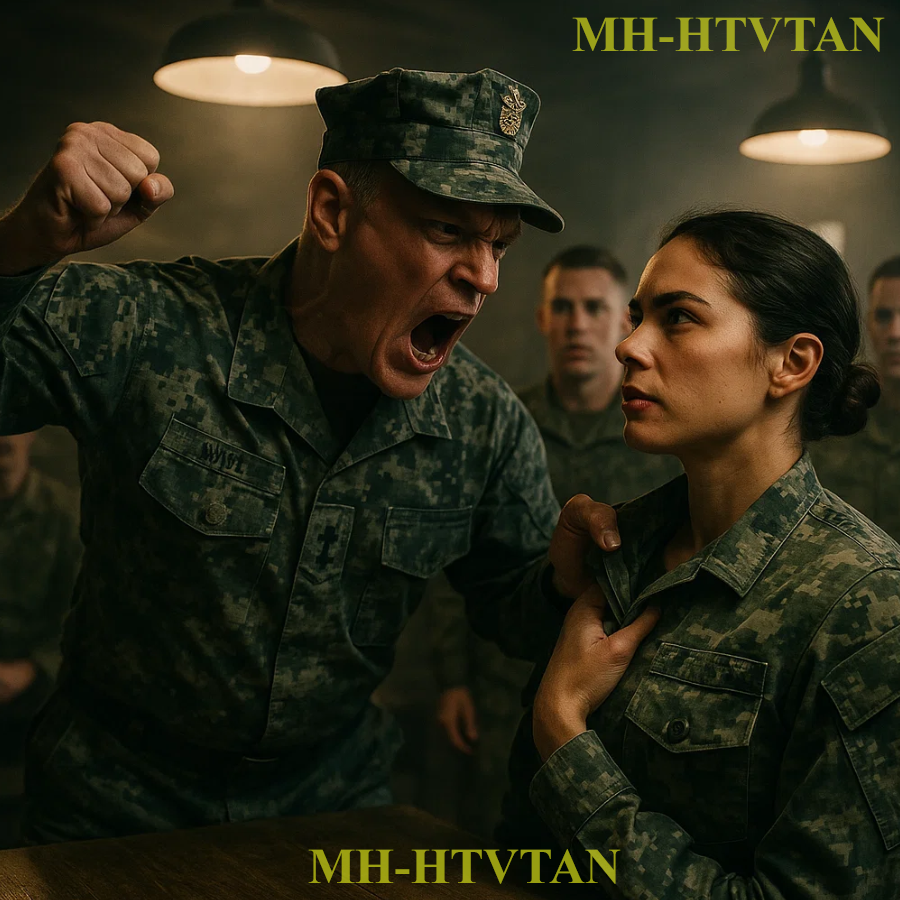

That made them laugh harder. Hayes leaned in close, told her stolen valor was a crime, said she should stop pretending before she embarrassed herself. She stood to leave. That’s when he grabbed her wrist. She pulled free easily, too easily with a control that came from muscle memory and training he didn’t recognize. That offended him.

He stood fast enough to knock his chair back. Told her she didn’t walk away when a marine was talking to her. Called her sweetheart. Told her to go home. Then he shoved her. She caught herself on the railing, tasted blood where her teeth cut into her lip. The bar went quiet. Hayes stood there, chest out, waiting for her to back down the way he expected women to back down. She didn’t.

Kira’s hands didn’t shake. That was the first thing she noticed. 4 years ago, they would have. Four years ago, she would have felt the adrenaline spike, the fear response, the fight orflight panic that untrained people experience when violence appears. Now there was just clarity. Cold mechanical assessment. Hayes outweighed her by 60 lb. He was drunk.

His balance was off. His friends were watching, which meant his ego was engaged. He’d already committed to aggression, which meant deescalation wasn’t an option he’d accept. She thought about her mother. Not the nurse who worked night shifts, but the woman who’d sat with the veteran in the ER at 3:00 in the morning, holding his hand while he came down from a flashback, speaking low and steady until he remembered where he was.

Her mother had taught her that strength wasn’t about force. It was about control. About choosing your battles and knowing when the fight mattered. This one didn’t. But Hayes was already moving. His fist came in wild and telegraphed. The kind of punch someone throws when they’ve never been taught to fight.

just told they’re tough enough to win. She could have slipped it. Could have stepped inside his reach and put him on the ground with any of a dozen techniques the Marine Corps had drilled into her during combat training. Could have made him regret every assumption he’d made about her. Instead, she let it land. The punch caught her jaw, snapped her head to the side. Pain bloomed sharp and immediate.

She tasted more blood. The room tilted then steadied. Hayes stood over her, breathing hard, looking almost surprised that he’d actually done it. His friends were silent now. The bartender was already on the phone with base security. Kira stayed on the ground, one hand pressed to her jaw, watching Hayes realize what he’d just done.

His face shifted from anger to confusion to something that might have been fear. One of his buddies grabbed his shoulder, said they needed to leave now, but it was too late. Two military police vehicles pulled up outside, light bars flashing red and blue through the bar’s front windows. Four MPs came through the door with the kind of purpose that said they’d done this before.

The senior man, a sergeant with a name tape that read Morrison, took one look at the scene and started separating people. Hayes tried to explain. Said she provoked him. Said she was probably lying about being a Marine. Said he was just defending the core from someone disrespecting the uniform. Morrison told him to shut up and sit down.

Another MP, younger, helped Kira to her feet and asked if she needed medical treatment. She said no. He asked for her ID. She handed over her common access card. He swiped it through his handheld and waited for the screen to load. His expression changed. Morrison came over. I looked at the handheld. His jaw tightened.

He asked Hayes if he knew who he’d just hit. Hayes said it was just some girl claiming to be a Marine. Morrison turned the screen so Hayes could see it. Staff Sergeant, military intelligence. Current assignment. Maroch. Hayes went pale. Hayes went pale. One of his friends asked what Marco meant. Morrison didn’t answer. Instead, he asked Kira if she wanted to file a complaint. She could.

Assault under Article 28. The investigation would bury Hayes for months, possibly ending his career before it really started. She looked at Hayes, saw a kid who’d made a stupid mistake, who’d let ego and alcohol override judgment. Saw someone who’d learned this lesson one way or another. She told Morrison no complaint.

Hayes stared at her like he didn’t understand. Morrison told Hayes he was being detained pending investigation. Told his friends they were all going back to base for statements. told Kira she should go to the battalion aid station and get her injuries documented even if she wasn’t filing a complaint. It would matter later. She agreed.

The battalion aid station was quiet at 11 on a Thursday night. A Navy corman who looked barely old enough to shave took photos of her split lip and swelling jaw, logged the injuries in her service treatment record, and asked whether she wanted the clinic to notify law enforcement and command or keep this as a medical entry only.

She said medical only. He looked uncomfortable but didn’t push. While she sat in the exam room waiting for discharge paperwork, Morrison came in. He closed the door behind him, which meant this wasn’t official business. He asked if she was really planning to let this go. She said yes. He told her Hayes was a problem.

Third incident in 6 months. Prior counseling for alcohol-related misconduct. This was the first time he’d gotten physical, but Morrison had a feeling it wouldn’t be the last if someone didn’t stop it now. Kira understood what he wasn’t saying. Hayes needed consequences, but consequences delivered by an MP report felt different than consequences earned through command channels.

One looked like punishment, the other looked like leadership. She asked Morrison to arrange a meeting. 2 days later, she sat across from Hayes in a conference room at the base legal office. His command had been notified. His platoon sergeant was present. So was a captain from his battalion who looked at Hayes like he was deciding whether the paperwork was worth it.

A JAG officer sat quietly in the corner advising on options. Kira didn’t raise her voice. She told Hayes about her mother, about the veterans who came through the VA with injuries no one could see. About the Marines she’d worked with down reign she’d saved her life. Who trusted her with theirs. who’d never once questioned whether she belonged because they’d seen what she could do when it mattered.

She told him that respect wasn’t about size or strength. It was about competence, about showing up when it was difficult, about trusting your people to do their jobs regardless of what they looked like. She told him he’d embarrassed himself, embarrassed his uniform, and embarrassed the core by assuming someone wasn’t capable based on nothing but his own prejudice.

Then she told him what happened next was up to his command. After discussion with the captain and platoon sergeant, Hayes was offered a choice. His command could seek non-judicial punishment under article 15, loss of rank, loss of pay, restriction to base, or he could accept command directed corrective action, mandatory counseling, temporary removal from leadership duties, and a formal letter of apology to be placed in his file and delivered to Kira’s command.

Hayes chose the second option. The letter arrived 3 weeks later. It was stiff, formal, clearly written under supervision, but it was there. Kira never went back to that bar. The story had already spread through Camp Pendleton, the way stories always spread in the military, fast, distorted, but carrying a core of truth that people recognized.

Hayes completed his counseling and returned to his unit. Morrison told her later that he’d changed. Not dramatically, but enough. He asked more questions, listened more, stopped assuming. Kira’s clearance paperwork moved a month later. Two months after the incident, her orders came through for another rotation with a joint task force operating in the Pacific.

The work would be classified. The victories would go unrecorded. But the mission mattered. Her last night stateside, she called her mother. They didn’t talk about the incident. Instead, they talked about small things. her father’s new route schedule, her sister’s nursing school applications, the weather in Duth.

Before they hung up, her mother said something she’d said a hundred times before. Take care of yourself out there. Kira promised she would. Hayes had gotten his second chance. What he did with it would define the marine he became. Kira had already moved on to the next mission.