At 6:12 a.m. on October 11th, 1943, in a stretch of occupied forest 20 km south of Lublin, the morning fog clung to the treetops like wet wool and turned the dirt road into a pale gray corridor. A pair of German BMW R75 motorcycles broke through the mist at 45 mph.

engines roaring at 4200 revolutions per minute followed by a third and fourth spaced in perfect convoy intervals of 7 seconds. These patrols ran the same route every Dawn 558 65612 precision drilled into them because the Vermach relied on motorcycle couriers for almost half of its field communication traffic in this sector. Every order, every map, every casualty report moved on two wheels.

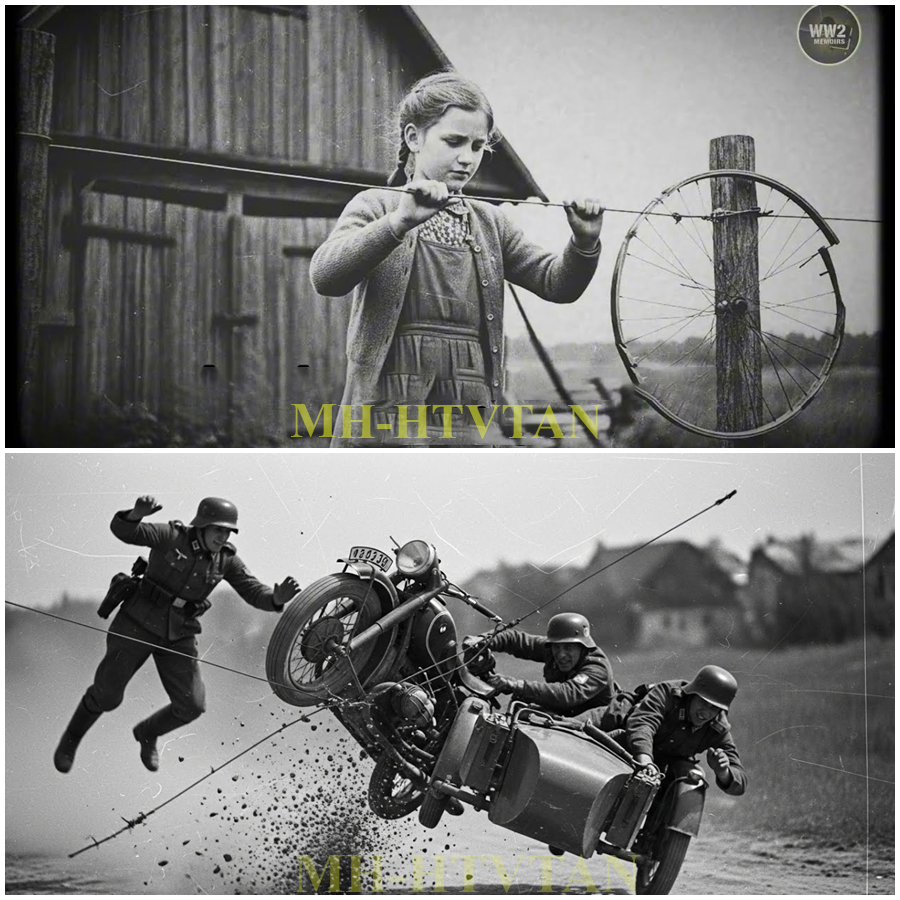

And in the past six weeks, at least 19 civilians had died for being on the wrong road at the wrong moment. What none of the writers knew was that 30 minutes earlier in the dark before sunrise, an 18-year-old farm girl named Hannah Weissaka had knelt beside a ditch with a coil of steel wire no thicker than a knitting needle, a rusted fence spike, and her father’s old pliers.

She measured the height of the first fence post by memory, 51 cm, the exact axle height she had observed when a German mechanic had lifted an R75 wheel to change a brake shoe 3 days prior. She had watched the mechanic work for less than 9 seconds, but it was enough to fix the number in her mind. 51, not 50, not 55. Axle center line, the number that mattered. The first motorcycle hit the wire at 61209. Not a sound beforehand.

No glint of metal in the fog, just impact. The front wheel locked instantly. At 45 mph, that meant a forward momentum of roughly 20 m/s, enough force to turn a 200 kg machine into a flailing projectile. The moment the wheel seized, the R75, pitched up as if yanked by an invisible hand, lifted clean off the ground, rotated 90 degrees, then slammed sideways into the gravel, throwing the rider into the ditch with a crack that cut through the fog like a snapped branch.

The second motorcycle swerved, break too late, skidded on a patch of wet clay, and tumbled after it. The third tried to pull wide, hit the fallen machines, and folded its front fork like cardboard three motorcycles down in under four seconds. The reports later said it must have been sabotaged with explosives or a mine.

Nothing else could have upended three German military motorcycles with trained riders on a dry weather route. But the truth was simpler and more humiliating. A single strand of salvaged hay barn wire stretched between two half-roed fence posts tightened until it hummed when Hannah plucked it with her thumb.

She had planted the posts 12 minutes before the convoy arrived, wedged the bases deep into the soft soil, and pulled the wire until her palms stung. She had timed everything off the sound of distant engines, the same engines that haunted her village every dawn. One detail made this morning different. Hannah was still there.

She should have left as soon as she finished tightening the line, but she froze when she heard the first engine, unable to tear herself away. She watched from behind an oak trunk, heart pounding against her ribs. Breath held until her vision blurred. The crash made her flinch, but she did not move. Not even when the fourth motorcycle skidded to a halt 40 meters ahead and the rider began shouting into the fog.

She counted 18 seconds before he reached for his flare pistol. She knew exactly how long it took for a flare to bring reinforcements from the checkpoint 600 m north, 50 to 60 seconds less if they had their truck idling.

She slipped backward through the underbrush, her boots nearly silent in the wet moss and vanished into the trees as the flare burst overhead in a sharp white bloom. When the German recovery team arrived at 614, they found two men wounded, one unconscious, one dead from a cervical fracture and three wrecked R75s sprawled across the road like broken toys. They searched for mines. They searched for tire spikes.

They found nothing. The wire was gone. Hannah had pulled it free as she ran, wrapped it around her waist beneath her coat, and disappeared into the forest path that only locals knew. Total material cost of her operation, one length of wire worth less than a loaf of bread and two fence staples she had pried off her family’s barn door.

Total damage inflicted three disabled couriers, one dead corporal, two wounded Lance corporals, and a torn hole in the morning schedule of a German garrison that prided itself on never missing a dispatch window. Viewers who believe that a detail as small as a single number 51 cm can shift the course of an entire patrol week should comment the number seven.

Those who think it is exaggerated should press like. Either way, ask yourself the question the Germans asked at 6:15 a.m. that morning. How could something this stupid work so perfectly? At 16, Hannah could lift a 50 lb sack of potatoes onto her shoulder without pausing for breath, rake a field faster than her older brothers and splice a broken fence line so cleanly her father said the cows would never know it had snapped.

The Weissaka farm sat 3 mi east of the forest road the Germans had converted into a courier artery, a route they used because radio sets in this region failed nearly 40% of the time thanks to distance terrain and constant Allied jamming. In 1943, the Vermacht recorded an average of 47 motorcycle dispatch runs per day between Krnik and Lublin.

Each one carrying orders that determined who lived, who starved, who vanished. Hannah had never seen a military map, but she understood the rhythm of those engines the way other girls understood music. The Germans came every dawn, every dusk. Same gears, same intervals, same impatience. Her father had been a blacksmith before the war.

Not a master craftsman, but good enough to shoe horses, straighten wagon axles, and repair farm tools with whatever metal scrap he could scavenge. Hannah grew up watching him twist wire test tension with two fingers. check hardness by the sound it made against the anvil. He could tell the difference between mild steel and highcarbon stock by tapping them together once. He never imagined those lessons would be used against an occupying army.

But after 1941, nothing in the village resembled the life they knew. The Germans confiscated half the harvest every season, took their mule for military requisition, and placed a checkpoint on the road where an officer once beat Hannah’s 14-year-old brother because he carried water after curfew. Two neighbors disappeared.

Three were shot. 19 were detained for aiding partisans. The pattern was obvious to anyone who bothered to count. It was the 19th disappearance that changed the way Hannah saw her world. A woman named Teresa, 43 years old, mother of two, vanished during a routine identity check. She had been carrying a small parcel of bread to her sister’s house.

Witnesses later learned she had been taken because a German corporal claimed she glanced suspiciously at an R75 patrol. Suspicion was enough to kill a person in 1943. The next morning, Hannah watched a convoy of five motorcycles roar down the same road at exactly 6:5 a.m. Exhaust echoing through the valley. The corporal who arrested Teresa leading the group.

That was the moment the constant drone of engines stopped being background noise and became a countdown. On September 14th, Hannah was delivering eggs to a German outpost, forced labor she could not refuse, when she saw two soldiers repair a courier motorcycle behind the stable. She kept her head down, pretending to sweep the walkway, but her eyes never left their hands.

She noticed the jack height, the wheel height, the brake drum markings, the way the mechanic leveraged the suspension to lift the front fork by a centimeter. He cursed because the bike sagged too low on the left, so he added a wooden block under the lower arm to center it.

Hannah memorized that block, 12 cm wide, 8 thick, 51 tall. She had seen her father stack identical blocks every winter to keep firewood off the mud. She did not understand torque curves, rotational inertia, or mechanical impulse. But she understood that if a front wheel caught something rigid at exactly the wrong height, at exactly the wrong speed, the rider would be thrown. She had seen it happen when her oldest brother hit a fallen branch on their field path.

The bicycle flipped. He broke his collarbone. If a small branch could do that at 12 mph, what could a taunt steel line do at 40? The village had whispered for months about sabotage attempts in nearby towns. Wires stretched across back roads, nails scattered in mud. Two cases had ended in executions.

One in Zamosi resulted in 14 people shot in the market square. Hannah heard every warning, absorbed every threat, but none of them outweighed the memory of her brother bleeding in the dust or Teresa’s empty kitchen table. When you are 18 in an occupied valley, the line between caution and paralysis is thin. She chose not to be paralyzed. She began testing in secret.

A broken bicycle wheel behind the barn. A piece of fencing wire stretched between two posts. She set the wire at 40 cm, too low. The wheel rolled over it. She set it at 60, too high. The wheel rattled but didn’t catch. She adjusted again and again until finally she found the height where the rim bit hard and stopped dead. 51. All was 51.

The number became an obsession. She carved it into a piece of scrap wood. She whispered it under her breath as she washed potatoes. She traced it in the dust when she was sure no one was watching. Her father noticed her studying the barn posts one afternoon. He asked what she was doing.

She lied and said she was fixing a sag in the gate line. He nodded unconvinced. People in wartime notice when a girl watches soldiers too closely when she counts their boots, their rifles, their motorcycles, but he said nothing. He simply told her that good wire hums when it’s tight and that bad wire hums only once. She carried that sentence with her for weeks, turning it over in her mind until it became a rule.

By late September, the Germans changed their courier schedule. More patrols, more urgency. Two new units passed through, raising the roads daily traffic to almost 60 motorcycle runs. Every engine that roared past the Wisaka fields tightened a knot in Hannah’s stomach. In 6 weeks, 19 villagers had been taken or killed.

The Germans were no longer a force of order. They were a clock ticking towards someone else’s disappearance. That was the catalyst. Not ideology, not orders, not grand strategy. Just a girl who had spent her entire life memorizing sounds, distances, angles, and the way metal behaves under stress. A girl who knew that on this road at this hour with these riders, a length of steel pulled to the right tension at the right height could do what rifles and partisans could not. Only she had noticed the number.

Only she cared enough to test it. And only she understood that sometimes an entire machine of war can be slowed by the smallest sound in the forest, a wire vibrating under a pair of worn pliers. At first, it was nothing more than a number in her head 51. But numbers in wartime become weapons when paired with the right mind.

Hannah tested the height again two days later by balancing a broom handle against the barn wall and marking the point where the wheel from the broken bicycle seized. All was the same mark. She dropped a plum line. Same result. Even the family’s old wheelbarrow wobbling on a bent axle locked against the wire at that height with a violent jolt.

She measured the distance with her fingers, then with a scrap of string, then finally with an offcut of oak from her father’s workbench. That oak piece became her gauge, her secret instrument, 8 in long, with a charcoal mark with a 51cm point lined up exactly. She hid it in her coat pocket like a talisman, and carried it everywhere she went. What she lacked in formal training, she made up for instinct, sharpened by survival.

She understood the terrain around her village as precisely as a surveyor. She knew which sections of road sloped half a degree toward the drainage ditch, which corners forced riders to lean left, which sections were shaded long enough for dew to linger past sunrise.

The Germans treated the forest road like a straight corridor. Hannah knew it was a trap waiting to be triggered. She began studying the daily courier rhythm with a precision that would rival a signals officer. The first patrol passed the field edge at 5:58 a.m. The second at 6:05, the third at 6:12.

A larger detachment rolled through at 7:30, then silence until noon. She logged these mentally noting variations of 30 seconds to a minute, depending on weather engine conditions and which non-commissioned officer led the route. She could identify half the riders by engine tone alone.

One morning she watched an R75 hit a pothole hidden beneath rainwater and nearly flip. The writer corrected at the last second, but the wobble told her everything her testing could not. A front wheel at speed is a fragile thing. The forces balancing it were precise, delicate. The Germans relied on discipline, uniformity, and routine. Machines did, too.

She began calculating not in formulas but in cause and effect at 40 mph. The front wheel completes nine full rotations per second. One instant of obstruction is enough to snap equilibrium. The rers’s weight becomes leverage against him. The motorcycle’s mass becomes a hammer. A wire, if tight enough, could force that instant.

What she needed was tension. Weak wire would sag and bend. Strong wire would cut bark but not stop metal. She walked the outskirts of the farm looking for options. Barbed wire was everywhere, but barbs snagged grass and drew attention. She rejected it. Snares used by trappers worked only on animals and snapped under heavy load.

She tested two different fence lines, pulling them with her father’s pliers until her hands blistered. The first wire sagged before humming. The second hummed almost immediately. She chose the second. It was cold drawn steel 3 mm thick, scavenged from a collapsed hay barn, abandoned the previous winter.

Its surface was pale with oxidation, but the core was still hard. She cut a 6 m length using a hacksaw that had three good teeth left. This was her ammunition. She practiced tying anchors without leaving obvious marks. She learned that knots weakened the wire by up to 30% and adjusted by looping around each fence post twice.

Instead, she tested tension by plucking the line the way her father plucked a balikica string, listening for the sharp metallic vibration that meant she was close to maximum load. When it vibrated too long, she loosened it. When it vibrated too little, she tightened it. In time, she learned that the wire’s perfect tension point produced a brief two-note hum, low, then high, like a voice clearing its throat. That was the sound of danger made visible.

She needed to know how to place the trap without being seen. German patrols changed patterns unpredictably. Some mornings they sent a single motorcycle first. Other days they sent four. She shadowed them from the treeine, memorizing gaps. On October 3rd, a courier team stopped near the bend to repair a loose muffler bracket.

She watched from behind an oak trunk, silent as a corporal hammered the bracket into place. The corporal cursed because the bolt thread was stripped. He tightened it anyway and left. Hannah noted the exact spot where he knelt. The bend was tight visibility, poor foliage thick. That location was ideal, a natural choke point. A rider approaching too quickly would be forced to adjust in a/4-second window.

A wire at axle height placed there would be invisible until the moment it bit. She practiced the entire sequence in her mind. Walk to the bend, drop to one knee, drive a st soil, loop the wire, cross the road, drive the second stake, pull, check height with the oak gauge, tighten until the line vibrated with the correct hum, brush soil back over the bootprints, step into the ditch to avoid leaving tracks.

retreat along the animal path that only locals knew. She rehearsed it again and again until she could do the motions without thinking. Time mattered. The window between patrols was narrow. She needed 90 seconds at most. On October 7th, she performed a full trial run in darkness. No wire yet, only the stakes and the timing. 93 seconds. Too slow.

She practiced again. 81 seconds. Better. She shaved seconds by carrying each stake under her arm instead of in her hands. She tied the wire in a coil she could unspool with one motion. She cut slits in her coat pockets so the pliers could hang inside, ready to grip. Every detail mattered. Small changes produced large effects.

The hallmark of all good engineering is simplicity under pressure. By October 10th, the decision was no longer a question of nerve, but inevitability. 19 villagers gone, more patrols, more arrests. The courier route had become a blade at the village’s throat. Hannah walked the road at dusk, touching the bark of the trees, counting the paces between trunks, memorizing how the shadows fell as the light faded.

She whispered the number again, 51. She pressed her fingers to the wire hidden beneath her coat. Tomorrow at dawn, she would make the road speak. At 4:59 a.m., the forest was a single unmoving shape, black and silent, except for the faint drip of condensation sliding from leaf to leaf.

Hannah crouched beside the ditch with the wire coiled around her waist like a second spine, the two stakes tucked beneath her coat, and the pliers hanging from her pocket slit where she could grab them without looking. She had rehearsed this moment so many times that her muscles moved before her thoughts did.

She stepped onto the road boot, sinking half an inch into the soft clay, and counted her strides to the bend. 23 to the first tree, nine more to the exact patch of soil where the corporal had knelt the week before. She could feel the cold rising through the ground as she pressed her weight onto one knee.

She drove the first stake in one motion, angled slightly toward the ditch to hold tension 16 cm deep, just enough to resist lateral pull, but not so deep that the Germans could spot disturbed soil later. The stake slid into place with a muted thud that blended into the wet earth. She looped the wire twice, pulled, once, felt the metal bite the wood. She crossed the road quickly, exactly the same 48 in she had marked in her mind, using the shadow of the leaning birch tree as her guide.

She drove the second stake, twisting her wrist hard enough to feel the tendons strain, then arked the wire across and pulled until her palm stung. She tied no knots. Only tension wraps the way her father had taught her. Wire weakens where it is bent. She checked the height with her oak gauge, too low by a centimeter.

She tightened again, the wire rising just enough to match the 51 cm mark. It hummed faintly as she tested it. A short, sharp vibration that died almost instantly. Perfect. She plucked it one more time. Two note hum. Even better. The entire process took 84 seconds. She had aimed for 90, but adrenaline shaved the extra seconds away.

She brushed soil over her knee prints, scattered a few leaves to mask disturbed patches, and stepped backward into the ditch where the fog was thickest. She pressed her back to the trunk every breath, slow, shallow, controlled. At 558, right on schedule, she heard the first engine, a low, distant rumble that grew into the familiar throb of an R75 running somewhere around 3800 revolutions per minute. She knew this one.

The lead rider used a richer fuel mix, probably to compensate for a worn carburetor needle jet. He always rode slightly faster than the others. She had counted at least eight times when he arrived 10 to 15 seconds ahead of the scheduled gap. Today, he came even faster.

The fog swallowed him until the moment he broke through it, riding low shoulders forward, head tucked, pushing at least 45 mph as he cleared the rise. Hannah forced herself not to flinch. At that speed, he would hit the wire in less than two seconds. She could hear the engine straining as he leaned into the curve. If he break at the wrong moment, the entire plan would fail. If he swerved wide, he might miss the line completely. Her heart hammered so hard she felt each pulse in her throat.

Then the moment happened. The R75’s front wheel met the wire exactly at axle height. There was no spark, no snap, no visible movement at first, just an abrupt, brutal halt. The wheel froze as if welded in place. The motorcycle’s momentum pitched the chassis upward, lifting the rear tire off the ground in a perfect arc.

The rider had no time to react. The machine flipped forward in a tight half rotation, slammed down sideways, and skidded 15 ft across the gravel before rolling into the ditch with a metallic crunch. The rider’s helmet hit the ground with a hollow crack. He didn’t move. The second motorcycle came 5 seconds later. He saw the crash too late.

He break hard, the tires shrieking against the clay, but the bike slid into the wreckage and toppled sideways. The third rider angled too far left to see clearly through the fog, attempted to swerve, but caught the edge of the fallen machine and flipped end over end. Hannah ducked lower into the ditch as debris scattered across the road shards of metal skittering over the surface like fleeing insects.

She waited exactly 18 seconds, the time she had learned it took for surviving riders to fire a flare. But no flare went up. The lone conscious rider was dragging himself out of the mud, coughing, reaching for his pistol. Hannah slipped backward into the underbrush, moving only when his face turned away, her steps muffled by the damp moss.

She felt the wire tug against her waist, where she had already begun pulling it free from the stakes. She wrapped it twice, three times, yanked until it came loose, coiled it beneath her coat, and vanished into the animal trail that wound behind the birch stands.

Behind her, the road was a ruin of steel wood spilled fuel and broken discipline. Three motorcycles disabled, one rider dead, two injured. A courier route paused for the first time in months. The Germans would not know what hit them. And even if they suspected sabotage, they would find no mines, no nails, no explosives. Only a mystery they couldn’t solve. Speed had trapped them. Routine had blinded them.

A single number had undone them. Hannah did not run. She walked steady and silent until the sound of the engines faded behind her. When she reached the ridge overlooking the fields near her home, she finally allowed herself to exhale. She glanced back once at the line of fog. She knew the pattern now. She knew the intervals. She knew the height. Today was only the beginning.

At 7:30 a.m., the recovery truck finally arrived. A two-axxle opal blitz rattling down the road with four armed soldiers riding on the side rails. The fog had thinned into streaks enough for them to see the wreckage scattered across the curve. Three R75 lay in a broken triangle frames bent forks. Twisted side cars crushed.

The corporal in charge, Reinhard Voss, 26 years old veteran of the Eastern Front, jumped off the truck before it fully stopped. He circled the scene with short angry strides, boots splashing through the clay jaw, clenched so hard the muscles twitched.

He had seen motorcycle crashes caused by potholes, by ice, by driver error. But three in the same spot in dry conditions on a known route impossible. His first instinct was mines. It was always mines. He barked orders. Two soldiers swept the verge for pressure plates, probing with bayonets. Another walked the ditch, looking for debt cord residue.

A fourth knelt beside the first wreck and inspected the brake drums. No scorching, no impact pattern from an explosion. nothing that matched previous sabotage reports. By 7:18, they had flagged 10 points on the road surface for inspection skid marks, gouges, fragments of headlamp glass. Voss walked the road with the confidence of a man accustomed to finding answers in details.

But today, every detail betrayed him. The skid marks began too late. There were no impact craters, no scorch rings, no fragmentation pattern, just three motorcycles that had toppled simultaneously as if struck by the same invisible force. He grabbed the limp front wheel of one R75 and twisted it.

The wheel rotated freely, bearings intact, no evidence of seizure. Yet the writer’s body position, thrown forward and to the right, suggested a violent stop. He called for the flare casings. None were fired. That bothered him more than the Rex. Riders trained to fire a signal within 10 seconds of danger. The absence of a flare meant they were taken by surprise so fast they never had time.

He crouched beside the lead bike and examined the axle housing. A faint thin scrape curved across the metal, almost too light to notice, unless the sun hit at the correct angle. He leaned closer. The mark ran straight and clean for 7 cm. It was not from a stone or branch. It was from something harder, something taut, something that struck the axle at a perfect height.

But the Germans found no wire, no anchors, no posts, only soil disturbed by the crash and the frantic bootprints of injured riders stumbling for footing. Voss rubbed the scrape with his thumb and frowned. He had seen marks like this once before on the Eastern Front near Smalinsk, where partisans had strung piano wire across a frozen road to maim dispatch riders. But that wire had left deep, violent cuts.

This scrape was light, almost delicate, as if the obstacle had been removed before anyone arrived. It made no sense. It contradicted every field manual he trusted. He ordered a 10-man search of the surrounding forest. They fanned out in a half kilometer ring rifles ready eyes sweeping the underbrush. They found nothing. No footprints except those from the crash. No broken branches. No trampled grass.

Whoever had done this understood exactly how to move through the forest without leaving a trail. By 8:0 a.m., frustration had turned to humiliation. They loaded the damaged R75s onto the Blitz truck and drove them back to the outpost. Voss wrote the first draft of his incident report at 8:42. He listed possible mechanical failure driver in attention and unknown environmental hazard.

He did not write the truth he suspected. If he wrote wire sabotage division headquarters would demand proof. He had none. By noon, the entire courier network had heard rumors. A patrol wiped out without gunfire. A bend in the road that flipped motorcycles without warning. Some said the road was cursed. Others said partisans had planted invisible traps.

For the first time in months, riders approached the forest curve at barely 20 mph. Eyes darting across the fog fingers hovering over their flare pistols. Delays cascaded up the chain of command. A dispatch that normally took 18 minutes now took 43. A ration order arrived 90 minutes late. An ammunition request never reached the forward platoon at all.

Every minute lost was a fracture in the machine that kept occupation power functioning. Division command reviewed the wreck photos at 200 p.m. and issued a directive. Increased patrols inspect the road. Hourly punish any failure to maintain schedule. But increased patrols meant more noise, more tension, more fear. Soldiers marched with fingers on triggers.

Civilians learned to hide sooner. The whole valley felt the shift, and Hannah, from the ridge behind her family’s pasture, watched the Germans move like ants over a kicked nest. They were agitated, uncertain, slower. That night, at 6:11 p.m., a squad of seven German soldiers patrol the same stretch of road, scanning the trees with flashlights.

Hannah watched from 50 m away, lying flat in tall grass. Her wire was gone coiled under a loose floorboard in the barn. She saw how they searched every ditch, every root, every scrap of bark. She saw their nerves jump each time a twig snapped. She understood something vital in that moment. Sabotage was not only about the damage done.

It was about the pressure it applied, the doubt it seeded, the time it stole. On October 12th, the Germans began setting checkpoints every half kilometer on the Courier route. On the 13th, they deployed a K9 unit from Lublin. On the 14th, they questioned 15 villagers from the area, including two boys no older than 12.

Three men were detained for suspicious behavior. All were released 12 hours later when the commanding officer realized the trap had required precise skill, not random resistance. He assumed partisans. He never once considered a farm girl. By the 15th, the courier officers altered doctrine. They ordered riders to travel in pairs, not alone reducing delivery speed by nearly 40%.

They mandated flare checks, brake checks, wheel checks. They formed a new rule approach all forest curves under 20 m hour. Every adjustment cost time. Every delay weakened the grip the Germans held on the valley. And all of it, every single change, came from a piece of wire worth less than a loaf of stale bread. Hannah saw the pattern forming.

She saw how a single disruption had multiplied into dozens. She saw how the Germans feared what they could not see or understand. She also saw something else. The road was no longer vulnerable in just one place. It was vulnerable everywhere. At 6:42 a.m. on October 16th, 5 days after the first crash, the German Courier Command logged an entry that should never have appeared in a system built on precision dispatch delayed. Cause unknown.

By noon, there were three more. By dusk 7, no mines reported, no combat activity, no weather obstruction, just a creeping invisible slowdown radiating outward from one forest curve. For an occupying army that depended on speed, this was not an inconvenience. It was a systemic failure. The region’s courier network normally processed an average of 40 to 60 motorcycle runs per day, moving everything from fuel tallies to troop repositioning orders. But now, riders crawled through the forest like hunted animals, stopping to inspect tree

trunks, probing the soil with bayonets, firing flares at shadows. A route that once took 18 minutes stretched to 40, then 50, then more than an hour. Under normal conditions, the Vermach expected a 97% dispatch completion rate. In the 72 hours following Hannah’s sabotage, that number dropped to 61.

Delays piled up, orders arrived late. Platoons acted without updates. Units moved without synchronization. Chain of command began to feel the tremors. The German 443rd Security Battalion responsible for the Valley logged two missed ration transfers, a fuel shipment delayed by 3 hours, and a resupply column halted because its motorcycle outrider didn’t arrive on time.

In the span of one week, not a single ambush, not a single bomb, not a single partisan firefight had caused these failures. The catalyst was one length of wire removed minutes after impact, leaving no trace except three destroyed motorcycles and the paranoia now spreading through the entire communications grid.

The pressure intensified on October 17th when a courier carrying artillery adjustment orders for a battery near Th Mudly Boris reached his destination 52 minutes late. Because of that delay, the battery fired on outdated coordinates. Three shells landed off target, wounding two German infantrymen and obliterating an ox cart belonging to a local farmer.

The afteraction report blamed transmission failure. But internally, officers whispered that something was wrong in the forest, something they could not detect. The idea unsettled them more than any partisan rifle. By October 18th, the Germans implemented a staggered dispatch pattern, sending motorcycles at irregular intervals to prevent predictable targeting. The theory was sound. The result was chaos.

Riders accustomed to fixed schedules misinterpreted each other’s movements. Two convoys nearly collided near the southern ridge. A patrol fired warning shots after mistaking another courier team for an ambush. The fog thickened that morning and for the first time the Germans slowed to 15 mph through the entire valley.

Every document, every directive, every correction rippled outward with built-in delay. At 9:14 a.m. that same day, Courier headquarters registered a pattern no officer could ignore. The number of runs completed between 600 and 100 had fallen by 45% compared to the previous week. By 40 p.m., the reduction hit 58%. By nightfall, the Germans faced the worst communication lag in the sector since the winter storms of 1941.

Hannah had not touched another wire since the first attack. Yet, the disruption expanded on its own like a fracture in glass. Fear did the work for her. Doctrine failed where uncertainty succeeded. The impact reached beyond courier lines. Patrol units reliant on quick updates became hesitant, waiting longer for confirmation.

Two squads arrived late to a scheduled search operation, allowing a group of displaced villagers to escape before arrest. A requisition order for two 400 rounds of ammunition. us never arrived because its messenger turned back after misinterpreting a rustle in the underbrush as movement. Rumor replaced procedure. Paranoia replaced confidence.

The German command attempted to compensate by assigning footrunners between outposts, a method at least three times slower and far more exposed. That same day, a runner carrying a map case slipped on wet shale and fell into a ravine, destroying half the documents. Another fainted from exhaustion after sprinting nearly 2 miles to meet a deadline. The courier system was collapsing, and no one understood why.

The logistical logs tell the real story. Before Hannah’s sabotage, motorcycles completed roughly 300 dispatch miles per day in the valley. In the 6 days after that number fell to and 72. Fuel consumption dropped 19% not because the Germans conserved, but because their couriers spent more time idling, checking, hesitating.

Average speed through the forest plummeted from 38 mph to 14. A system designed for momentum had been forced into a crawl. And though the Germans blamed partisans, whether mechanical failure or discipline lapses, the truth was simpler.

Every delay, every stutter, every miscommunication stemmed from a single idea executed with absolute precision. A wire pulled tight to 51 cm. The fear of what could not be seen was more powerful than any explosive. It made every tree a potential trap, every corner a threat, every broken twig a warning. It taught the Germans the most dangerous lesson in occupied territory. When the occupier cannot predict the local mind, the occupier loses control.

Hannah did not know the full extent of what she had done. She only saw the couriers move slower. The convoys fall behind schedule, the patrols linger in confusion. She did not see the battalion logs, the delays, the frustration building at headquarters. She could not read the German reports describing the valley as unstable, but she sensed it.

She felt it in the tension of the air, in the way soldiers glanced over their shoulders as they passed her village, in how their voices rose when a distant engine misfired. Her sabotage had become a shadow cast over the entire region, stretching far beyond her intention. It had started as one strike.

Now it shaped the rhythm of occupation. and the Germans with all their machinery, discipline, and doctrine had no countermeasure for an enemy they could not see, predict, or understand. At dusk on October 22nd, a week after the first crash, the valley finally exhaled. The patrols thinned. The checkpoints relaxed.

The couriers rode slower, but no longer in convoys of four. Fear shifted from sharp panic to a dull, lingering caution. The Germans believed the danger had passed. The truth was simpler. The army had adjusted to its own paralysis. The disruption had become the new normal. Hannah, meanwhile, returned to her daily routines as if nothing had changed.

She carried water from the well- gathered potatoes from the frost hardened soil fed the hen’s chopped wood in the shed. But inside her barn, hidden beneath the floorboard where her father stored old horseshoes, lay the coiled wire. She touched it only once that week, not to use it, but to remind herself it was real.

The valley had slowed without additional sabotage. She did not need to strike again. The first act had done enough damage to echo outward into everything the Germans touched. Yet she could not forget what she saw the day after the crash. A German corporal limping from the wreck, interrogating an old man near the roadside.

The man couldn’t have been more than 65, shoulders bent, hands blistered from lifting sacks. The corporal shoved him twice, demanded he explain why the road had turned against them. The old man wept, stammering in broken German. The corporal struck him across the face, and stalked away. Fear moved through people like wind through wheat, silent, invisible, reshaping everything.

What Hannah never saw, what no one in her village saw, was the German meeting at the Lublin outpost on October the 24th. A conference room filled with maps, dispatch logs, and the smell of damp wool. The officers reviewed reports from the valley, 15 late dispatches, 12 incomplete runs, one missing courier, three unexplained crashes. The regional commander, Oburst Vilhelm Ratomacher, tapped his pen three times on the table before speaking.

Courier disruptions of this magnitude had occurred only twice before once in Bellarus, where partisans mined a 5m stretch of road, and once in Ukraine, where early winter ice crippled an entire regiment. But this, a temperate valley in October, no storms, no mines, no gunfire.

Yet the pattern resembled a textbook example of organized disruption. He asked a single question. How many partisans operated in the valley? The room answered with silence. Because intelligence had no names, no sightings, no weapons caches, no gunfire exchanges, nothing. That uncertainty alarmed Ratomacher more than any confirmed threat.

An enemy that could not be mapped was an enemy that could not be contained. His solution was predictable Titan patrol grids. Increase village surveillance. punish sabotage with severity, but his measures only hardened local resentment, which in turn created the very resistance he feared. It was a cycle he could neither detect nor break.

On October 26th, the valley recorded the first courier-free hour since the occupation began. Not a single engine passed along the forest bend between 600 and 700 a.m. unprecedented. Riders had started avoiding the route entirely, choosing the longer road through a marsh basin four kilometers east. That road took 40 extra minutes. It flooded easily.

It turned to muck after rainfall. Trucks bogged down, horses strained, yet the couriers preferred it. A bad road was safer than a haunted one. What Hannah didn’t know was that her strike had triggered an intelligence re-evaluation. The Germans now classified the forest bend as zone of special vulnerability, a designation normally reserved for mind bridges and partisan borderlands.

Division command drafted a memorandum advising future units to avoid the sector entirely. One girl had diverted an entire artery of movement without firing a shot. Winter pressed in early that year. By mid- November, the rains had turned to sleet, and the marsh road east became almost impassible.

Supplies moved slower. Patrols arrived wet and shivering. Soldiers complained about frozen fuel lines and swollen boots. Tension rose, discipline cracked. A junior officer struck a courier for arriving late. Another filed a report accusing a sergeant of hoarding fuel. Friction mounted between units forced to compensate for failures they couldn’t explain.

The valley groaned under the weight of problems that had one origin and no solution. Through it all, Hannah remained invisible. The Germans never searched her house, never questioned her family, never imagined that the architect of their disruption milked cows at dawn and mended shirts by the fire.

They looked for a partisan leader, a sabotur with military training, a man. They did not look for a girl who sharpened her knives on the same wet stone her father had used since before the war. But the valley remembered. In January 1944, when the Germans tightened their grip during a harsh winter crackdown, villagers whispered about a girl who had slowed the war. They didn’t know her name. They didn’t know she was 18.

They didn’t know the exact height of the wire or the careful planning that preceded it. They only knew that one morning the forest swallowed three German motorcycles and returned nothing but wreckage and something changed after that. Something subtle, something steady. Hannah lived to see the war end. The Germans withdrew. The Red Army arrived. New uniforms replaced old ones. New dangers replaced old fears.

She married in 1949, lived in a house 3 kilometers from the forest bend. raised two children, kept her father’s tools in a box beside the stove. She never spoke of the sabotage. Not to her husband, not to her children. The wire remained hidden under the barn floor until 1983 when her son dismantled the boards to repair a rotted beam.

He brought it to her confused, holding the coil of rusted steel. She only smiled and told him to leave it where he found it. When she died in 1991, local historians found fragments of her story through interviews, rumors, and one partially preserved German report describing the courier failures of October 1943.

The report mentioned no sabotur, no explanation, only the phrase unknown disruption in forest transit corridor. That was her legacy. Small cause, large effect. A line drawn through through the machinery of war by a girl who never sought recognition. A wire that hummed only once but echoed for weeks.

And somewhere in the valley, where the road still bends between the birch trees, local farmers say the fog sits thicker than anywhere else, as if it remembers the moment speed met silence.