At 6:12 in the morning on August 27th, 1944, a sound rolled across the eastern districts of Warsaw that survivors would later describe as a metallic thunderclap sharper than any artillery round they had heard in four years of occupation. It came from the railway line near Praga, a seemingly routine stretch of M49 steel that had survived air raids demolitions, and sabotage attempts.

But at that exact second, a charge no heavier than a family loaf of bread tore open the joint between two rails, snapped the four hardened bolts of the fish plate, and sent a 400 ton armored train lifting off its tracks as if an invisible hand had struck it from beneath. Witnesses said the first explosion was quick. A single violent crack followed by a deeper roar as ammunition inside the front cars ignited.

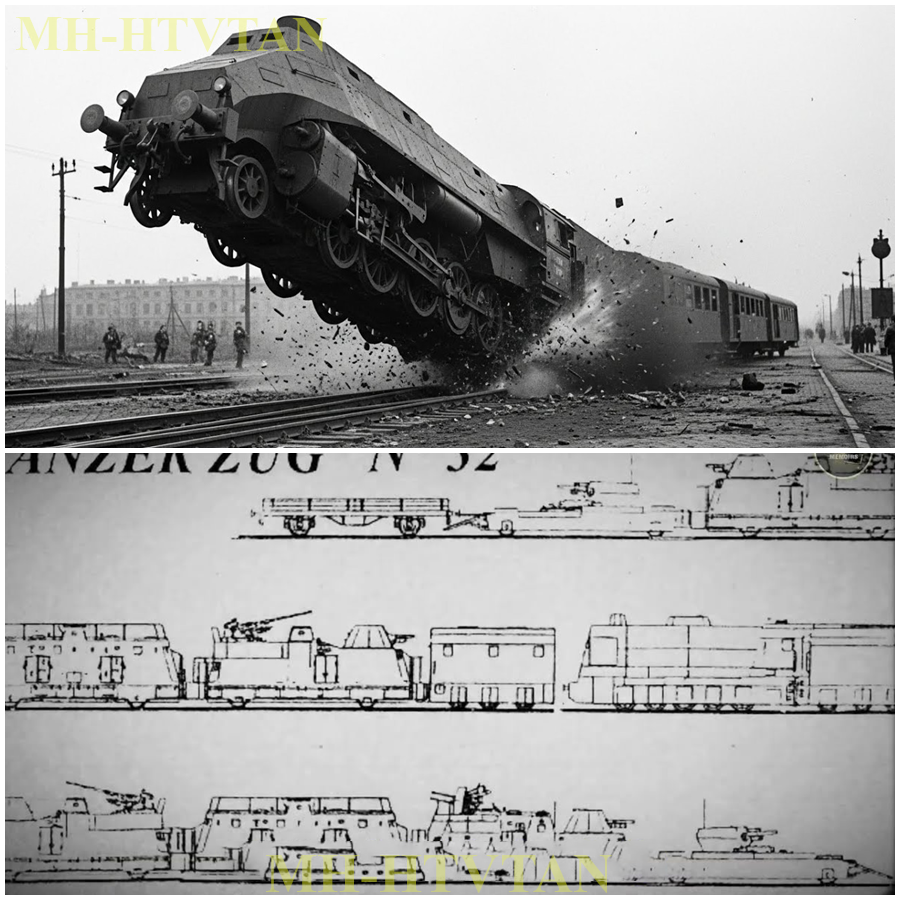

Not a bomb dropped from a stooka, not a shell from a tank. A small blast placed at exactly the right point. A blast that no German patrol saw coming. The armored train was Panzer Zoo 77, a rolling fortress built from eight armored cars, each plated with steel up to 45 mm thick.

It had dominated the Warsaw districts of Praa Grochov and the river approaches for weeks. its 75 millimeter gun leveling apartment blocks in minutes. Its machine gun sweeping entire intersections. The train weighed over 380 tons in its light configuration and over 400 tons when fully loaded with munitions and infantry.

It could shrug off anti-tank rifles, mines, and even direct artillery fire if the angle was shallow. Nothing short of a heavy demolition charge placed directly beneath the wheels could it. That was the theory. The morning of August 27th destroyed that theory in one violent motion. The front car jumped upward by more than a foot before slamming down sideways. The coupling snapping like a twig.

The second and third cars twisting with it. Steel screamed. Rail ties exploded into splinters. A wave of pressure rolled outward. The Germans on board thought they had hit a mine planted by professionals, maybe a resistance engineering unit, maybe a British supplied explosive. They had no idea the device weighed barely a kilogram and a half. They had no idea it had been carried to the rails inside a teapot.

The shock wave ran through the neighborhoods like a siren. Civilians ducked instinctively, afraid of Luftwafa raids. Those close to the line described bricks shaking loose windows rattling for several seconds and then the unmistakable scent that always follows high-grade ammonium-based explosives. Sharp metallic dusty like burned fertilizer.

They would learn later that the explosion was not an attack by soldiers, not a partisan detachment, not a sabotur with military training. It was the work of a 19-year-old girl from Warsaw’s old town. a courier, a girl who until then had carried nothing more dangerous than coated messages and rolls of medical bandages. Her name was Zofhia.

Her weapon was an enamel teapot with its bottom cut out and its belly packed with a mixture of aminal and powdered aluminum. And somehow it had ripped open the only armored train the Germans trusted to suppress the capital’s uprising. To understand why the Germans panicked that morning, you have to understand what Warsaw was at that point in the war.

Four years of occupation had crushed the city. 1,300,000 people had lived there in 1939. By the summer of 1944, less than half remained. Entire districts were rubble. The Warsaw uprising had erupted only weeks earlier. An act of defiance by the army of Krajoa against a collapsing German administration. But the Germans still held the firepower.

They had tanks, aircraft, artillery, and the armored trains that patrolled the rails like steel predators. Panzeroo 77 in particular had become a symbol of invincibility. Residents knew its schedule by sound alone, the grinding metallic hum at dawn, the echo of its autoc cannons. It was the nightmare. They could not escape.

For the uprising to hold even a single neighborhood, that train had to be stopped. But stopping it seemed impossible. The tracks were patrolled every hour. German engineers inspected bolts, joints, and couplings daily. Mines larger than 5 kg could not be laid without detection. Charges smaller than that lacked the force to cut a rail that weighed 54 kg per meter.

The Germans had numbers. They had radios. They had armored patrols. And over all of that, they had a belief that no civilian would dare come within 20 m of their rails without being shot. They were wrong. What happened at 612 that morning was a combination of physics, timing, and audacity. The explosion happened at a curve near kilometer marker 11.

4, where the rails bent just enough to create lateral load on the wheels. If a rail joint were weakened there, even a slight shift could generate catastrophic derailment. Resistance intelligence had learned this from railway workers who risked execution to pass along blueprints. Over 4 days of observation, the team recorded the train speed approach angle and breaking pattern.

The sweet spot was that bend at the 11 km mark where the train slowed to around 24 km per hour. Enough speed to topple it, not enough to flatten the charge before detonation. But the part that still overwhelms me even after reading three separate accounts is this. The device was delivered by one person walking calmly along the track at dawn carrying what looked like an ordinary household teapot. It weighed maybe 3 lb.

You could hide it in a bread basket. You could walk past a patrol with it and no one would look twice. And that precise invisibility was its deadliest advantage. The Germans saw weapons everywhere except where the real weapons hid. If you believe the smallest actions in war can change the fate of a city, comment the number seven. If you do not believe that, hit like to disagree.

And if you want more stories like this, subscribe. so you do not miss the next chapter. At dawn on the day before the explosion, Zofhia stood in the basement of a collapsed tenement on Breesca Street, staring at an object so ordinary it felt absurd. A teapot, white enamel, blue rim, the kind every Polish household owned before the war, the kind used to warm milk or boil water for soup.

It weighed almost nothing, but the bottom had been cut away, cleanly, replaced with a thin steel plate, handshaped by a machinist who had not touched legal metal work since 1940. Inside that hollow shell, there would soon be enough explosive power to split a rail that weighed over 100 lb per meter, a kettle that could a train. The idea had started as a joke.

According to one underground report, a resistance sapper named Merik once remarked that the Germans searched every toolbox, every satchel, every crate, but never once bothered to check what people carried to cook with. Zofhia heard the comment. She remembered it. And then she realized something the men had missed.

The most effective disguise in occupied Warsaw was not military, not industrial, but domestic. Women carrying food containers were invisible. Mothers with kettles, cans, bowls, jars. None were considered threats. The Germans feared rifles, pistols, grenades. They did not fear an enamel pot. But behind that simple insight, was something harsher.

For four years, Zofhia had watched her city stripped of dignity, one law at a time. Curfews, deportations, public executions. She had watched German patrols shove old women aside with the same boots they used to kick down doors. She understood something the occupiers never did. That a girl who has seen her family dragged away her street, shelled her home burned no longer thinks of objects as innocent.

A pot can be a pot or it can be revenge. She held it carefully while Merrick measured the cavity with a strip of folded paper marking half an inch intervals calculating how much ammonal would fit. 1 and 1/4 kg was the safe estimate. Enough to shear the bolts on a fish plate. Enough to lift the first axle of a locomotive.

Enough to guarantee the crew inside had no time to respond. He scraped the enamel with his fingernail and nodded. It was sturdy. It would not rupture prematurely. It would channel the blast downward into the rail. The charge itself had been assembled over two days from stolen industrial chemicals, ammonium nitrate scraped from fertilizer sacks, aluminum powder hammered from cooking sheets, TNT shaved from captured German demolition blocks.

The mixture was illegal, unstable, and deadly in the wrong humidity. But in the hands of the underground engineers of Warsaw, it was routine work. What was unusual was the combination of the charge with a timer. Most resistance bombs in 1944 were trip wire or pressure triggered, but putting a pressure trigger on the rails risked premature detonation under a patrol wagon.

A timer was the only option, and timers that could withstand vibration were rare. Zophia provided the solution without knowing she had done it. She had once delivered a broken Vermached alarm clock to a man who repaired watches before the war.

He discovered that the German model, despite its cheap casing, had an exceptionally strong mainspring and a reliable minute hand rotation, perfect for a delayed pullpin mechanism. When she mentioned this to the sapper unit, they handed her the clock its guts exposed like a wounded animal. This is your firing system, they told her. You will set it yourself. She felt the weight of that instruction like a stone.

Through the cracked basement window, she could hear the rumble of Panzeroo 77 moving through Praa. It passed every morning around 610. Its sound carried through the city, the grinding of steel flanges, the deep thud of armored wheels on uneven rails. Residents could distinguish that train from tank columns by ear alone.

It had become the voice of occupation, and she was about to silence it. They briefed her quickly. Too quickly. The timing of the train was stable within a window of 5 minutes, rarely earlier or later. German patrols along the track near kilometer marker 11.4 rotated every 40 to 60 minutes.

Dawn was the safest time because patrols changed shifts. She would walk along the embankment like a girl searching for scrap metal or fallen coal. She would kneel beside the rail as if tying her shoe. She would place the teapot directly beside the fish plate, not touching it, not more than a hands width away. Closer than that drew suspicion. Farther weakened the blast. The path to the target was not long, but it was exposed.

a stretch of 200 meters of open ground broken only by a telegraph pole and the remains of a bombed out fence. If a single sentry glanced the wrong way, the mission ended in arrest and execution. Even that word execution had become commonplace in Warsaw, spoken with a detached familiarity that masked how quickly life could vanish. Zofhia knew the risk.

Yet, when the sapper team asked if she was certain she could do it, she nodded before they even finished the question. She spent the evening studying the clock mechanism, memorizing how far she had to turn the dial to create a 7-minute delay. Not 6, not 8, 7.

Enough time for her to walk away with a normal pace and vanish between the ruined stairwells of a burnt apartment block. She practiced setting it in the dark. She practiced while listening for footsteps. She practiced with her hands shaking, then practiced again until they stopped shaking. That detail appears in a post-war testimony, and when I read it, I realized something.

You cannot train courage, but you can train precision until it becomes a shield against fear. On the night before the sabotage, she slept only a few minutes. The city never slept anyway. Artillery rolled, buildings groaned, fires burned out of sight. And yet there was a strange calm in her mind, the kind that comes when a person has accepted the danger and focused entirely on the task.

When she stepped out of the safe house at 5:30 in the morning, the teapot wrapped in cloth inside a wicker basket, she walked not like a sabotur, but like a factory girl heading to work. and that in occupied Warsaw was the most powerful camouflage imaginable. If you believe an object as simple as a teapot can become the sharpest weapon of a resistance comet, the number seven.

If you do not believe that hit, like as a challenge, and subscribe if you want to follow the next steps of this operation, because what happens when she reaches the tracks at dawn is even more unbelievable than the preparation. At first glance, an armored train seems like an artifact from another century, a relic that belongs to the age of steam and empires.

But in 1944, for the German army fighting in occupied cities, it was one of the most reliable weapons they possessed. And Panzer Zoo 77, the machine that dominated the eastern districts of Warsaw, was not a museum piece. It was a 400tonon moving fortress engineered to crush urban resistance with a mixture of brute force shock and psychological intimidation. The Germans did not merely deploy it.

They depended on it to hold the city together as the uprising spread. And that dependency becomes clearer the more closely you examine its construction. The train consisted of eight armored cars. Each car weighed between 40 and 60 tons depending on configuration. The armor thickness ranged from 12 mm on the upper panels to over 40 mm on the angled plates that shielded the heavy guns. Think about that for a moment.

40 mm of hardened steel sloped at an angle to deflect incoming fire. Enough to stop a rifle bullet and anti-tank round, even the blast from a medium caliber shell. The Germans did not build armored trains as curiosities.

They built them as mobile artillery platforms capable of laying down continuous fire in dense urban terrain where tanks struggled to maneuver. The forward car mounted a 75 mm gun weapon with a muzzle velocity high enough to pulverize brick buildings in two or three shots. Behind it, two flat cars carried machine gun nests with 6 to 12 MG34s or MG42s weapons that could fire up to,200 rounds per minute each.

The train also carried anti-aircraft cannons, typically the 20 mm flak 38, which doubled as anti-infantry weapons when pointed horizontally. You could not flank it. You could not outrun it. Whatever it saw, it could hit. Whatever it hit, it could destroy. And then there was the psychological effect. Residents of Warsaw could distinguish Panzeroo 77 by the sound alone.

Survivors compared its approach to the deep metallic role of an approaching storm. Children memorized the timing of its patrols the way others memorized church bells. The way its weight pressed into the rails produced a unique hum, a vibration felt in the soles of the feet before the train even appeared.

When that vibration came, you moved. Because minutes later, the streets it crossed would become kill zones. But for all its firepower, armor, and presence, the train had one vulnerability its designers never fully solved. It depended on a thin pair of steel rails to carry its entire mass. Two rails each, no wider than a handspan.

Each a long strip of M49 profile steel that weighed just under 55 kg per meter. Rails that were joined end to end by small rectangular plates known as fish plates. Four bolts per joint. Eight bolts per rail segment. If the plates failed, the rail failed. If the rail failed, the train failed. Simple physics yet often overlooked. And this is where the story begins to tilt. German engineers understood the risk.

They inspected the rails daily. They tightened every bolt. They replaced cracked fish plates. They installed patrols that walked the embankment at intervals of 40 to 60 minutes. They placed centuries at bridges, culverts, and curves. But they also made a mistake, a very human one.

They underestimated how much force a small charge could deliver when applied with precision to the rail joint. They assumed anything that could shear four hardened bolts would have to be large, bulky, and impossible to hide. They assumed saboturs would target the train itself, not the rails. They assumed no one would ever have the courage to approach the track at dawn, while German boots still echoed along the length of it. There is something almost intimate about a rail joint when viewed up close.

Two rectangular metal plates each, maybe a foot long, pressed against the ends of the rails held by bolts thicker than a thumb. When pressure travels across the joint at speed, the fish plate bears the stress. If the bolts are loosened even slightly 2 mm, 3 mm, the joint becomes unstable.

Under the mass of a locomotive weighing over 70 tons per axle, the instability magnifies exponentially. A shift of 3 mm can create a vertical displacement of several centime, enough to pop a wheel, enough to throw an axle sideways, enough to start a chain reaction. Engineers who studied derailments know this well, and so did the underground rail workers who passed intelligence to the resistance.

They reported that the curve at kilometer marker 11.4 had an angle of roughly 4.8°. Not steep, but enough that any lateral distortion at the joint would be amplified by the weight transfer of the locomotive as it leaned into the turn. If a charge were placed precisely beside the fish plate, not under it, not in front of it, but beside it, the downward blast would rip the bolts free, twist the plate, and deform the rail. You did not need a 5 kg mine.

You needed precision. According to one post-war reconstruction, Panzer Zoo 77 approached the curve at a speed of about 24 km per hour. Too fast to avoid derailment once the joint failed too slow to power through it. The perfect speed for disaster. The driver, unaware of any danger, guided the locomotive into the turn with a routine confidence of someone who had done it every day for weeks. Crewmen stood at their posts.

Gunners waited inside the armored casemates. No one expected anything. Why would they? The rails had been inspected not long before. The patrol had seen nothing unusual. A teapot in the grass was nothing unusual. But here is the part that fascinates me because it reveals something deeper about warfare. The Germans trusted the machine. They believed in the weight, the armor, the speed, the routine.

They built a 400 ton symbol of control and expected it to dominate by sheer presence. What they did not consider was that the machine itself created predictability, a predictable path, a predictable speed, a predictable target. When you apply pressure at exactly the right point, even a Titan becomes fragile.

In tactical reports from the uprising, German officers described armored trains as psychological stabilizers, meaning they restored a sense of dominance simply by crossing a troubled district. Losing one was not just a mechanical failure. It was a symbolic wound. It showed the population the Germans were not invincible.

It showed the garrison that the enemy was capable of striking at will. And most importantly, it showed the resistance that ingenuity could match steel. If you think even the strongest machines have a weakness waiting to be found, comment the number seven. If you doubt it, hit like to disagree and subscribe so you do not miss what happens next.

Because the way Zofhia used that vulnerability was even more precise than the engineers who built the train. At 5:20 in the morning on the day of the attack, the air over the rail line near kilometer marker 11.4 was cold enough to sting the lungs. The sky was a washed out gray, the kind of color that makes shadows disappear, and distances seem shorter than they are.

It was the hour when night patrols were returning to their posts and day patrols had not yet settled into their rhythm, the single narrow gap in German discipline that the resistance had learned to exploit. Zofhia stood 150 yards from the curve, her wicker basket resting against her hip, the teapot inside wrapped in a cloth that once held bread. The detonator was armed. The clock mechanism was ticking.

She had only minutes to complete a sequence of movements that had taken 4 days to plan. The design of the operation was as simple as it was unforgiving. The team had tracked Panzeroo 77 schedule across four mornings. 22 km per hour at the straightaway, a rise to 24 at the curve, slowing no more than a handful of seconds at the garrison crossing.

They marked how long it took the locomotive to appear after the first faint hum reached their listening posts. 48 seconds on average. That number mattered. It meant that once the train entered audible range, any sabotur near the rail had less than a minute to act, less than a minute to kneel, place the charge, set the teapot down at precisely the right angle, and walk away without looking hurried. That single insight decided the entire method.

But placing the charge was only half the story. The other half was choosing where to place it. Curve 11.4 was not just convenient. It was mathematically perfect. When a locomotive weighing over 70 tons shifted its weight into a curve, the lateral load across the outer rail increased by nearly 70%. Combine that with a slight elevation difference and you have a pressure point.

When a blast hits from the side at that exact point, the force multiplies, not linearly, exponentially. German engineers had calculated these figures when constructing the line. They never imagined those same figures would be used against them. Ammonell, the explosive mixture inside the teapot, was notoriously sensitive to impurities. Moisture could reduce its power by half.

Too much aluminum powder and it burned rather than detonated. But the sappers who prepared the charge measured everything by weight. And feel the way a baker knows dough by touch. 1.3 kg of ammonal mixed in a ratio that maximized brisence, the suddenness of explosive shock.

Enough to generate a pressure wave exceeding 2,000 pounds per square inch within a confined space. Enough to snap eight hardened steel bolts and yet small enough that Zophia could carry it with one hand. The firing mechanism was even more delicate. The Vermach travel alarm clock she used had a main spring enough to withstand vibration and a minute hand that moved in clear, predictable increments.

When rewired to pull a safety pin free at a predetermined moment, it became a simple but reliable delay trigger. 7 minutes was the window chosen. Long enough to get clear. Short enough that the train would strike the joint while the blast shock was still propagating through the steel. To reach the fish plate, she had to cross a patch of rubble and descend the shallow embankment. From there, the rail was only 6 or 7 ft away.

The fish plate was where two 15 m lengths of rail met. Four bolts on each side worn from years of weather and war. They looked solid. They were not. Two bolts had hairline fractures invisible to a casual inspection. That detail came not from luck, but from intelligence gathered by railroad workers who risked immediate execution for aiding the resistance.

They had passed this information through coded notes tucked inside loaves of bread delivered to safe houses that change location every night. Zofhia reached the rail at 537. She knelt as if tying her shoe. She set the teapot beside the fish plate not touching it because contact could alter the blast pattern. The teapot had to sit 12 to 18 cm away from the rail closer and it would punch upward instead of sideways. farther and the blast might disperse into the soil.

Every centimeter mattered. She could hear nothing but her own breath and the faint ticking inside the metal shell. She rotated the alarm clock dial. One click, 2, 3. Each click represented one minute of delay. She stopped at the seventh click. The trigger arm inside the kettle trembled slightly as the tension engaged.

She felt it rather than saw it. That tiny tremor meant the device was alive. It also meant there was no going back. If she slipped, if she bumped the teapot, if a patrol appeared, if someone shouted a challenge, if she panicked, the mission ended with her death.

She stood brushed dust from her skirt and walked away at a measured pace. She did not run. Running was suspicious. Running would draw attention. Her footsteps were slow at first, then quicker once she passed the telegraph pole that marked the halfway point to safety. According to underground testimony, she counted her steps.

110 steps to the broken brick wall, 70 more to the stairwell, 25 to the concealed doorway of the safe house. If she reached that doorway before the train entered the curve, the mission would succeed. If she didn’t, she would be discovered. Behind her, the clock inside the teapot ticked toward detonation. Ahead of her, the faint vibration of the approaching armored train crept through the ground. The timings were converging like two blades closing on the same point.

She never looked back, not once. And that decision, in its simplicity, may have saved her life because patrols are trained to watch those who look over their shoulders. I find myself returning again and again to this sequence. Not because of the explosion, but because of the calculation behind it. The operation was not improvisation. It was a blueprint.

A blueprint of physics timing human nerve and a battlefield where ingenuity mattered more than firepower. This is what makes small acts of sabotage so devastating. They use the enemy’s predictability against him. If you believe that precision, not strength, is often the deciding factor in war, comment the number seven. If you think otherwise, hit like and subscribe so you do not miss what happens when the locomotive finally reaches the curve.

At 6:10 in the morning, the first vibration reached the soles of Zofhia’s shoes. Not a sound yet, just a tremor. The kind of low-frequency shutter you feel before you hear anything at all. Panzer Zoo 77 was still hundreds of yards away, but 400 tons of armored steel announced itself long before it appeared.

She kept walking the ruined stairwell now, only 50 paces ahead, her heartbeat matching the rhythm of the distant rails. She did not dare count the seconds. She already knew them. The detonator had been set for 7 minutes. She had used almost all of them. The train crossed the straightaway at roughly 24 km per hour.

Its locomotive pushing the weight of the seven armored cars behind it. German doctrine dictated that armored trains never slowed more than necessary near urban zones because slow trains became easy targets. But the Praga curve forced even heavy locomotives to ease off the throttle. Engineers estimated the reduction at 2 to 3 km hour.

A small change insignificant to a civilian, but in derailment physics, that margin is everything. Too fast and the train hops the rail with enough momentum to recenter itself. Too slow and it simply grinds over the joint. But at 24 to 22 kmh, the mass shifts perfectly into the weak point, a razor thin window where devastation becomes unavoidable.

At 611 and 37 seconds, the locomotive entered audible range. The hum became a growl, then a grinding metallic roar. Civilians in nearby apartments recognized the sound and ducked by instinct, pressing their bodies against whatever solid walls remained. Those who lived near the tracks had learned the tremors. This one felt wrong, stronger, rougher, like the engine was dragging something heavy beneath it. Zofhia slipped into the blackened stairwell.

She exhaled once slow and controlled the way she had practiced the night before. Her entire body was still. She did not look back. She did not need to. The detonator’s timing was exact. The Germans relied on discipline. She relied on precision. At 612 and 0 seconds, the main spring inside the Vermach travel clock released its final unit of tension.

The brass arm snapped forward. The safety pin slid free. The firing pin punched into the primer. A spark ignited the ammonal mixture, converting 1.3 kg of powder into a shock wave faster than the blink of an eye. The teapot jumped, the ground heaved, and the rail joint, the simple metal seam that held together two 15 m segments of steel, erupted.

A blast wave of over 2,000 lbs per square inch drove sideways into the fishblade, shearing all four bolts in less than a tenth of a second. The joint twisted. The left rail shifted outward by nearly 3 in. 3 in was nothing in ordinary space. On a rail line carrying a 70 ton locomotive into a curve, 3 in was fatal.

The locomotive’s leading wheel struck the misaligned rail at 612 and 1 second. Metal screamed. The wheel climbed the twisted edge, rose upward, lost contact with the track entirely, and slammed down into gravel. The second wheel followed. The axle snapped sideways. The entire front bogey lurched into the air. All 70 tons of it lifted by its own catastrophic momentum.

Inside the cab, the engineer had no time to react. He saw nothing unusual, felt only a sudden violent jolt, and then the world turned sideways as the locomotive rolled. In the armored compartment behind him, gunners were thrown against steel walls. Ammunition crates broke free, scattering shells and high explosive rounds across the carriages.

When the second car slammed into the derailed locomotive, several shells detonated sympathetically. The explosion tore open a seam in the armored plating and propelled a column of smoke 60 m high. Residents watching from a distance said the blast looked like a factory chimney collapsing in reverse. First a plume of dust, then a rising tower of black smoke.

The earth shuddered beneath their feet. Three windows shattered on Kajka Street. A chimney cracked on Targoa Avenue. People who had spent years living under air raids still flinched, unsure whether the thunderous impact was an Allied bomb, a German mortar, or something else entirely.

Inside the stairwell, Zofhia pressed her hand over her mouth to steady her breathing. The shock wave arrived half a second after the visual flash. Dust drifted down from the ceiling. For a heartbeat, the city was silent. No gunfire, no orders, no footfalls, just the echo of 400 tons of machinery collapsing into itself. Then came the chaos.

German officers shouting, infantry scrambling down the embankment, medics running toward the wreckage, a siren wailing from the far end of the line, crewmen stumbling out of overturned cars, dazed, bleeding, unable to process what had hit them. It was impossible. A charge that small should not have had that effect. A civilian could not have carried it. A patrol should have seen it.

And yet the train lay broke and split open like a cracked shell. Its aura of invincibility gone in a single moment. From her hiding place, Sophia heard the confusion ripple outward. She did not smile. She did not cry. She simply closed her eyes for a second, not in relief, but in acknowledgement, because she knew what this meant.

Not the destruction of a train, but the destruction of a myth. The Germans believed the armored train made them untouchable. Now they would realize they were not, and the people of Warsaw would realize the opposite. I have read several post-war reports on this derailment, and each time one detail stands out to me. Not the physics, not the explosives, not even the timing. It’s the scale mismatch.

A 400tonon machine designed by military engineers, crewed by trained soldiers, supported by patrols, defeated by one person with a teapot and 7 minutes of courage. That asymmetry is the essence of resistance warfare. It is the moment when steel yields to intent.

If you think this kind of precision strike proves that willpower can overpower machinery, comment the number seven. If you think the Germans simply made a fatal mistake, it’d like to register your disagreement and subscribe to follow the next phase because the consequences of this derailment were larger than anyone in that stairwell could have imagined. At 6:13 in the morning, less than 60 seconds after the derailment, German command posts in Praga registered the first frantic radio transmissions from Panzer Zugoo 77’s crew. The messages were clipped. Chaotic overlapping. The operators could not

understand what had happened. An explosion, a derailment, smoke inside the forward casemate, possible secondary detonations, no confirmation of enemy contact. It was the kind of report that made officers freeze because nothing in their manuals explained how a 400ton armored train, supposedly immune to partisan sabotage, could be knocked off the rails by a strike no one saw coming.

The tactical consequences unfolded immediately. The armored train had been scheduled to conduct suppressive fire on three districts that morning. Its 75mm gun was to soften resistance barricades near Targoa and Zumovska. Its machine gunners were to assist infantry units preparing to retake the intersections the resistance had seized the night before.

Without the train, German infantry lost their rolling fortress, their elevated gun platforms, their mobile morale anchor. They were blind in sectors they usually dominated and hesitant to advance into streets they previously considered safe. But the derailment did more than disrupt a patrol route. It triggered a cascade of logistical failure that would stretch across the city.

The rail line that Panzeroo 77 used was the central artery for shuttling ammunition fuel and reinforcements between garrisons. With the train sprawled across both rails, the route was effectively severed. Any movement of supplies now had to divert through longer, slower, more exposed paths. German reports show delays of up to 4 hours for resupply convoys that day.

In street fighting, 4 hours is a lifetime. Repair crews were dispatched, but they faced obstacles they had not anticipated. To clear the wreck, they needed heavy cranes capable of lifting over 50 tons at a time. The nearest functional rail crane was stationed miles away in a sector already under fire. Moving it required securing the entire route, but resistance units used the derailment window to launch ambushes.

They struck patrols, disabled trucks, severed communication lines. Every time German forces tried to regroup, the shock of losing the train echoed through their ranks like an aftershock. And then there is the strategic layer, the part that reveals the real depth of this moment. Armored trains were not merely machines.

They were symbols, instruments of psychological dominance. They crossed districts not only to kill, but to project inevitability, to remind civilians and partisans that the Germans could appear anywhere, any time with overwhelming firepower. When that symbol lay broken on its side, its steel peeled back, its wheels twisted upward like an animal carcass.

Something shifted in the minds of those who witnessed it. Residents emerged from doorways, some cautiously, some boldly. Resistance fighters exchanged looks that no written report could capture, a mixture of disbelief and recognition. They had not only injured the occupier, they had humiliated him. A weapon meant to inspire submission had instead revealed vulnerability.

I think about this often when studying uprisings. Machines can reinforce domination, but when they fail publicly, they collapse the illusion of control faster than any speech or leaflet ever could. German officers understood the problem instantly. Their reaction was severe. 230 soldiers were deployed to secure the rec site. 14 new guard posts were established along the line.

27 civilians were detained and interrogated, some beaten, all suspected of aiding the sabotage. But even inside the German command structure, the derailment sowed panic. Internal memos recorded phrases like unforeseen capability, subversive technical knowledge, and enemy possesses engineering proficiency beyond expectation. That last phrase is the most telling.

It admits a psychological defeat. It admits they underestimated their opponents. The derailment also altered German defensive planning. Without Panzeroo 77, they were forced to commit armored cars and halftracks to compensate. But those vehicles were vulnerable to Molotov cocktails mines and barricades.

The train had been the one armored asset that could not be easily targeted. Now it was gone. And in war, removing a single keystone can make the entire structure shift. Tactical decisions become compromised. Morale fractures. Discipline erodess. Meanwhile, inside the resistance camp, the effect was the opposite.

Zofhia’s sabotage, though anonymous to most fighters, became an instant catalyst. Word spread that the invincible train had been destroyed. Fighters who had spent weeks losing ground now believed momentum was shifting. Civilians who had been hiding in sellers felt embers of hope. Even partisans in distant sectors heard the news and began planning attacks on German infrastructure with renewed confidence.

What fascinates me most, more than the explosion, more than the derailment, more than the physics, is this asymmetry. A single act by a single person disrupted the strategic rhythm of an occupying force. Not temporarily, fundamentally. It forced the Germans to acknowledge that the resistance could strike at their strongest point.

And once that belief enters the collective imagination of an insurgency, it does not leave. There is a line in a post-war Polish journal that struck me deeply. When the train fell, the fear fell with it. That is the legacy of sabotage. Machines can be repaired. Rails can be replaced.

But psychological shock radiates outward, touching everyone, combatants, civilians, officers, generals, and it changes the battlefield in ways charts cannot measure. If you believe that destroying a symbol can be more powerful than destroying a weapon, comment the number seven. If you think the train was only a machine and nothing more hit, like to disagree and subscribe to follow the final chapter because the story does not end with the wreckage.

It ends with what the derailment revealed about the limits of occupation. At 6:14 that same morning, as German soldiers swarmed the smoking wreck of Panzeroo, 77, Zofhia stepped out of the stairwell and blended into the flow of civilians moving through Praga’s shattered streets.

Not one person knew that she had just altered the psychological landscape of the uprising. Not one person knew that she had carried a bomb the size of a teapot into the beating heart of the occupier’s confidence. And she never volunteered that information later. The war would end. Lives would be rebuilt. Histories would be written. But her name stayed buried in resistance logs overshadowed by louder events and more famous commanders.

That anonymity to me is what separates real resistance from legend. It is the quietness of it, the refusal to claim glory where survival is reward enough. After the derailment, Zofhia moved deeper into the network of safe houses. She continued courier work, transporting coded notes, maps, antibiotics, and the kind of small essential messages that hold an underground army together.

In the chaos that followed the destruction of the train, countless Polish civilians suffered retaliation. Entire blocks were searched. People were dragged from buildings. Uniformed men shouted for answers no one could give. Sophia walked past them every day carrying only what she needed.

The memory of the explosion lodged somewhere inside her like a splinter she could not remove. She had not just survived the most dangerous act of her life. She had created a moment that radiated through the uprising. Shifting, morale, shifting, belief shifting what people thought was possible. What does a city become when it realizes its occupier can bleed? That is the deeper question that emerges from this story.

One derailed train will not win a war. It will not overturn an army. It will not reverse the tides of destruction that had already swallowed Warsaw whole, but it pierces something more fundamental, inevitability. Occupation relies on the belief that the occupier cannot be stopped.

When that belief collapses, even for a moment, the ground under the occupier’s boots becomes less certain. History records battles and troop movements, divisions and logistics, but the human mind is often the true battlefield. And in 1944, for the first time in months, the people of Warsaw saw an icon of German invincibility lying on its side like a wounded beast.

There is a moment documented in a resistance diary that captures this shift. Later that morning, a group of underground fighters passed the smoke plume rising over Praga. One of them reportedly said, “If the tracks can be broken, the city can be broken free.” It was not strategy. It was not military logic. It was belief.

And belief is what sustains an uprising when ammunition runs low and food disappears. The derailment gave that belief new life. From a historian’s perspective, the operation is a study in asymmetry. A small charge, a domestic object, a 19-year-old courier, 400 tons of armored steel, an entire occupation force jolted into reaction.

When I examine these details, what I see is a pattern repeated across many conflicts. The most decisive moments are often shaped not by firepower but by nerve, not by rank but by opportunity, not by armies, but by individuals who refuse to accept that the world is fixed in its current shape. And there is something else here, something human.

Zofhia did not become a symbol, not during the war, not after it. She did not write memoirs. She did not sit for interviews. She did not claim the title of sabotur or hero. She lived quietly after the war the way so many resistance fighters did. But the act remains. Her moment of precision, her seven minutes of courage, her teapot, the most ordinary object in a city ravaged by brutality, reshaped into a tool of defiance.

That detail stays with me because it reveals a truth about human agency. Power is not fixed. systems are not invulnerable and sometimes the smallest gesture in the smallest window of time can strike the largest structure in the world. In one German postwar analysis, a senior engineer described the derailment as anomalous. His meaning was technical.

The blast pattern was smaller than expected for the amount of damage inflicted. The physics did not align with the models. But there is another meaning embedded in that word. Anomalous. Outside prediction, outside control, outside tyranny, a disruption where none should exist. That is what resistance is. A series of anomalies that accumulate until the occupier’s certainty erodess.

To close this story, I want to leave you with the image that persists in my mind. A teapot resting beside a rail. A girl walking away at dawn. A locomotive entering a curve. A shockwave rewriting the rules of what seemed impossible. If that moment tells us anything, it is that history is not only shaped by generals and governments.

It is shaped by those who stand in the margins and decide quietly, deliberately to push back. If you believe this act shows that a single mind can alter the trajectory of a city, comment the number seven. If you believe machines, armies, and empires alone write the outcome of wars hit, like to disagree and subscribe so you never miss the real stories behind the myths, the forgotten names behind the battles, and the moments when ordinary people change the course of History.