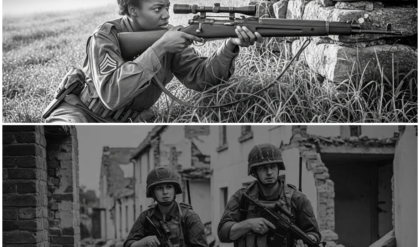

Texas, summer of 1944. The morning sun climbed over Camp Hern, casting long shadows across the pasture where a 17-year-old German soldier knelt in the dust, cradling a newborn calf in his arms. His uniform was faded, his hands gentle, his eyes wet with tears he didn’t bother to hide. Klaus Vber had worn a soldier’s face for 2 years.

But here in this impossible moment, he was just a boy again. Klouse had enlisted at 15, not from conviction, not from patriotism. But because the recruiters came to his school in Stoutgart in the autumn of 1942, and promised adventure, promised purpose, promised everything except the truth. His mother signed the papers with hands that trembled.

His father had already been gone 2 years somewhere on the Eastern front, his letters arriving less frequently until they stopped arriving at all. By 16, Klouse was in North Africa with the Africa corpse. A boy among men, carrying a rifle that felt too heavy and wearing boots that gave him blisters that never quite healed.

The desert was nothing like the recruitment posters, just sand and heat and flies, and the constant waiting punctuated by moments of terror so intense they seemed to exist outside of time. He was captured at Casarini Pass in February 1,943. The American soldiers who took him prisoner were surprised by his age.

One of them, a sergeant from Ohio with kind eyes, offered him chocolate from a ration pack. Klouse ate it slowly, savoring sweetness he’d almost forgotten existed. The sergeant asked his age in broken German. When Klouse answered 16, the American shook his head and said something in English that sounded like sympathy or maybe regret. From North Africa, Klaus was shipped to a processing center in Algeria, then across the Atlantic on a crowded transport that took 3 weeks.

the ocean gray and endless and terrifying in its vastness. He’d never seen the sea before the war. Now he was crossing it in chains, heading to a country he’d been taught to fear, a nation of supposed savages who would treat prisoners with cruelty. The propaganda had been specific, detailed. Americans were brutal, driven by greed, incapable of human compassion.

Their cities were cesspools of violence. Their soldiers were animals. Everything Klouse had learned in school. Everything whispered in training camps. Everything repeated until it became a kind of truth. All of it painted America as a nightmare dressed in the flag of false democracy. The reality was confusing.

The guards on the transport ship were professional, sometimes even friendly. The food was better than what he’d eaten in the Africa corpse. When Klaus got seasick, a medic brought him medicine and spoke to him gently in German that carried a Midwestern accent. Nothing matched what he’d been told.

The disconnect was disorienting, like waking from a dream into a world that followed different rules. They arrived in New York Harbor in April 1943. Klouse stood on deck with hundreds of other prisoners, watching the Statue of Liberty, emerge from the morning haze, green and enormous and utterly foreign.

An older prisoner, a corporal named Ernst from Munich, spat at the site, but Klouse just stared. He’d expected to feel hatred or fear. Instead, he felt only a strange hollowess, a sense of being a long way from anything that resembled home. From New York, they traveled by train, P cars with barred windows and armed guards through a landscape that seemed impossible in its scale. Germany could fit inside America dozens of times over.

The forests were bigger. The rivers were wider. The farms stretched to horizons that made the eye ache with distance. Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri. Each state was larger than German provinces. Each city a monument to industrial capacity that made Klouse understand finally why the war would end the way it had to end.

They reached Texas in late April when wild flowers painted the roadsides in color so bright they hurt to look at. The train slowed as it approached Camp Hearn. A new facility still being completed. Guard towers raw lumber against the sky. barracks arranged in neat rows, wire fences gleaming in the sun. Close pressed his face against the window, watching the landscape rolled past, cattle grazed in endless pastures.

Horses stood in the shade of oak trees. Farmhouses sat distant and white, American flags hanging limp in the still air. It looked nothing like Germany, nothing like the desert, nothing like anywhere Klouse had been or imagined. The train stopped with a lurch of couplings and compressed air.

Guards opened the doors, sunlight flooding in, heat washing over the prisoners like a physical wave. Texas in April was already hotter than Stoutgart in July. The air was thick, humid, carrying smells of grass and dust, and something sweetlouse couldn’t identify. Camp Hearn held 4,000 prisoners by summer 1944. Most were Africa corpse veterans, men in their 20s and 30s who’d fought across North Africa before capture. But there were boys, too, dozens of them.

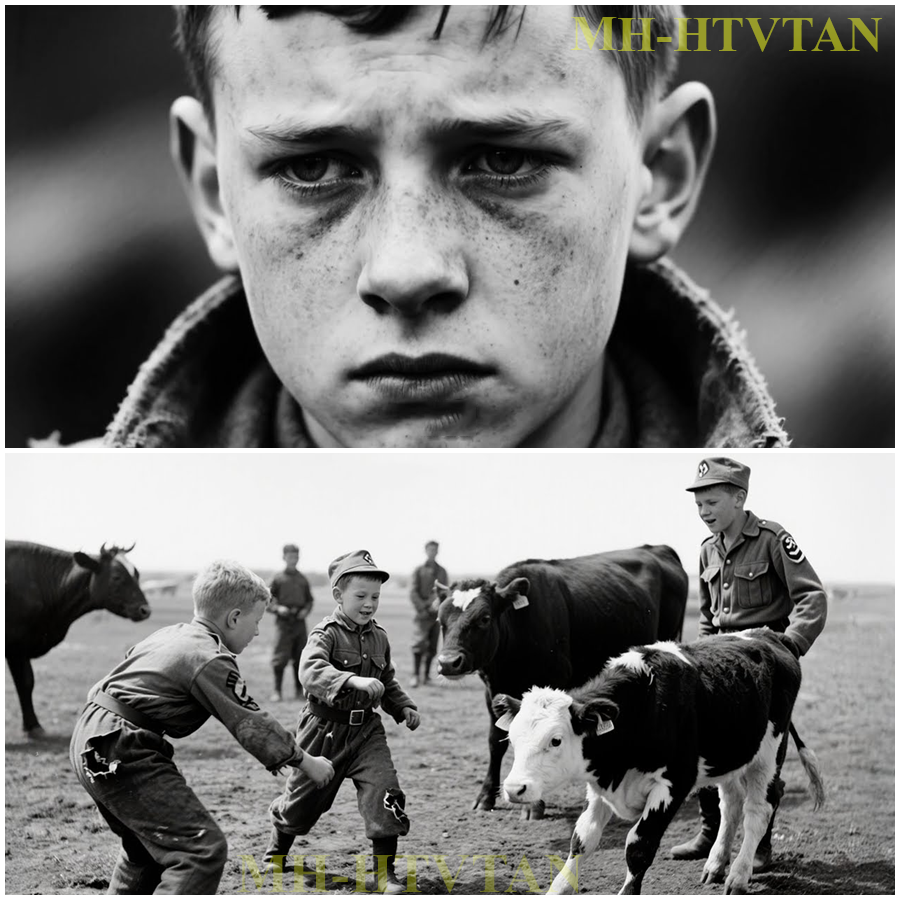

16, 17, 18year-olds who’d lied about their age or been conscripted young, who’d seen combat before they’d seen life, who wore uniforms that never quite fit and carried expressions that aged them beyond their years. Klouse was assigned to compound B barracks 7. His bunkmate was Hans Keller, 17, captured in Tunisia, a farmer’s son from Bavaria who spoke with an accent so thick the northern Germans mocked him for it.

Hans missed his family’s dairy farm with an intensity that bordered on physical pain. He talked about it constantly. The smell of the barn, the sound of the cows, the routine of milking that marked time in a way that made sense. The camp routine was bearable. Morning roll call. Breakfast in the messaul.

Work assignments. Evening meal, lights out at 10:00. The work varied. Some prisoners were sent to local farms to help with labor shortages. Others maintained the camp itself. Still others made furniture or worked in the laundry or performed the thousand small tasks required to keep 4,000 men fed and housed.

Klouse was initially assigned to kitchen duty, peeling potatoes, washing dishes, hauling supplies. It was boring work, mindless work, the kind of work that gave the mind too much time to wander. He thought about his mother, about his sister, about whether his father was alive or dead, about the war continuing somewhere far away while he peeled potatoes in Texas. The American guards were professional but distant.

They didn’t fraternize, didn’t share much beyond orders, and occasional small talk. The camp was run efficiently by the rules with the Geneva Convention guidelines posted in German and English. Prisoners received mail, Red Cross packages, access to a library, permission to stage plays and concerts.

It was captivity, yes, but it was captivity bounded by law and international agreement. Nothing like the rumors that had circulated in the Africa corpse about American treatment of prisoners. By midsummer, the camp had settled into a rhythm. The Texas heat was oppressive temperatures climbing past 100°. The air so thick it felt like breathing through wool. Men worked slowly, deliberately conserving energy.

The barracks at night were ovens, sleep difficult, temper short. That’s when Major Henry Parker arrived to implement the camp’s agricultural work program. Parker was a Texan, 53, a rancher before the war, who deep been commissioned to manage the prisoner work program because he understood both farming and men.

He was tall and weathered, with eyes that squinted even in shade, hands calloused from decades of work. He spoke no German, but made himself understood through gesture and tone, and an interpreter named Fiser, a German American from Fredericksburg, who’d grown up bilingual. Parker’s proposal was simple.

Prisoners would work on surrounding ranches and farms, helping with labor shortages caused by American men being overseas. The work would be varied planting, harvesting, fence repair, livestock management. Prisoners who worked well would earn small wages deposited in camp accounts available when they returned home after the war. Klouse volunteered immediately. Not for the money, what use was money here, but for the chance to be outside the wire, to do something that felt useful, to escape the monotony of camp life, even if only for a few hours each day.

Hans volunteered too, hoping for farmwork, hoping to be near animals again to reconnect with something familiar in this foreign land. They were assigned to the Morrison Ranch 12 miles southwest of camp. The ranch was 5,000 acres of cattle and horses, owned by a family that had worked this land for three generations. Jack Morrison was 60.

His son was in the Pacific. his ranch hands had gone to war or defense plants, leaving him desperately short of help during the busiest season. The first morning, Klaus and Hans rode in the back of a truck with eight other prisoners, guarded by two soldiers, who looked barely older than the prisoners themselves.

A drive took them through country that seemed empty of everything except spacewire fences running to horizons. Windmills spinning lazily, cattle scattered across pastures so large you could lose a German village in them. The Morrison ranch house was white clabbered with a wide porch surrounded by oaks that provided islands of shade in the sea of grass.

Barns and corrals clustered nearby, painted red, wood silvered by sun and wind. Jack Morrison stood in the yard, hands on his hips, watching the truck arrive with an expression that held skepticism but not hostility. Fiser, the interpreter, made introductions. Morrison nodded, looking at each prisoner in turn, his gaze lingering on Klouse and Hans, perhaps noting their youth.

He said something in English. Fisher translated, “You folks will be helping with cattle work, branding, fence repair, general maintenance. You work hard, we’ll treat you fair. You cause trouble, you go back to camp. Simple as that.” Klouse nodded. Hans nodded. The other prisoners nodded. Morrison seemed satisfied.

They started with fence repair hot tedious work under the Texas sun, stringing new wire, replacing rotten posts, the kind of labor that made your back ache and your hands bleed through work gloves. But it was outside. It was useful. It was something other than waiting. At noon, Morrison’s wife brought lunch sandwiches and lemonade served without comment or ceremony.

The prisoners ate in the shade of a live oak. guards nearby but not hovering. The lemonade was cold and sweet, shocking after months of tepid water and Aerzot’s coffee. Klouse drank slowly, trying to make it last, trying to understand this strange American hospitality toward enemy soldiers. After lunch, Morrison called Klouse and Hans over.

Fisher translated, “Got a job that needs a gentle touch. Newborn calves in the south pasture. Need vaccinating and ear tagging? You boys know cattle? Hans’s face lit up. He spoke in broken English. Words tumbling over each other. Yes, farm Bavaria. Cows. Milk gesturing to communicate what language couldn’t. Morrison studied him, then nodded.

All right, then. Let’s see what you can do. They drove to the south pasture in a battered Ford pickup. Morrison at the wheel. Klouse and Hans in the bed with the guard bouncing over ruts, dust billowing behind them. The pasture was enormous, dotted with cattle herfords, mostly red and white. Mothers with calves that couldn’t be more than a few weeks old.

Morrison parked near a corral. A guard stayed with the truck, rifle across his lap, but not threatening, just present. Morrison handed Klouse a bag of supplies syringes, vaccine bottles, ear tags. He demonstrated the process on one calf quick efficient practiced. Then he stepped back and nodded at Hans. Your turn.

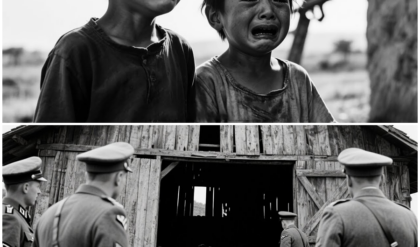

What happened next would become one of those moments that existed outside normal time that stretched and deepened and became more significant than its surface detail suggested. Hans approached a calf that was lying in the grass, its mother nearby, watchful. He moved slowly, speaking softly in German, the same tone remembered farmers using back home.

That universal language of gentle authority that animals understood regardless of the words. The calf struggled briefly when Hans knelt beside it, then settled, perhaps sensing his comb. Hans ran his hand along the calf’s neck, feeling for the injection site. His movements were tender, automatic muscle memory from a life before uniforms and rifles. He administered the vaccine smoothly, tagged the ear, then sat back on his heels, still touching the calf, his hand resting on its flank.

That’s when Klouse saw his friend’s face crack. Hunts shoulders shook. Tears started, silent at first, then coming with gasps that he tried to muffle. He bent forward, forehead pressed against the calf’s side, one hand still stroking its neck, and cried with the abandon of someone who’d been holding everything in for too long.

Klouse moved to him instinctively, knelt in the grass beside his friend. He didn’t say anything. What could be said? They were 17 years old, a thousand miles from home, wearing enemy uniforms, crying over a calf in a Texas pasture because it reminded them they’d once been children, once had lives that made sense, once existed in a world where touching animals was normal and comforting and not a shocking reminder of everything they lost.

Morrison stood by the truck watching. He didn’t speak, didn’t rush them, just waited, his weathered face unwreadable, giving them this moment because maybe he understood what it meant. Or maybe he just understood that sometimes people needed to fall apart before they could function again.

The guard looked uncomfortable, but didn’t intervene. Fiser, the interpreter, was very quiet. After a few minutes, Hans wiped his face with the back of his hand, leaving dirt smears on his cheeks. He looked at Klouse, embarrassed, defiant, grateful. Klouse nodded. “I know, I know.” They finished vaccinating the calves.

Hans worked with his hands steady again, his face composed, but something had shifted. Klouse could see it, could feel it in himself, too. The calf had opened something, not just memory, but recognition. They were children, still children. Wearing uniforms didn’t change that. Carrying rifles didn’t change it.

Being prisoners of war in Texas didn’t change it. The work at Morrison Ranch became routine. 3 days a week, Klouse and Hans were trucked out with other prisoners, returning to camp in the evening, dusty and exhausted and somehow more human than they defelt in months. The ranch became a kind of sanctuary, a place where they could temporarily forget they were soldiers, forget they were prisoners, forget they were enemies in a war they hadn’t chosen. The calves were the center of it.

Morrison had a spring cving season that year. dozens of new births that needed attention. Klouse and Hans became the calf specialists, trusted with the delicate work of vaccinating, tagging, treating minor ailments. Morrison showed them how to bottlefeed calves whose mothers had died or rejected them, how to mix formula, how to hold the bottle at the right angle so the calf wouldn’t choke.

Feeding a calf was meditation. You sat in the barn or the shade of a tree, the calf between your knees, bottle in hand, and focused on nothing except keeping the flow steady while the calf sucked with desperate enthusiasm. The world narrowed to that simple exchange nourishment given. Life sustained, and for those minutes the war didn’t exist.

Hans thrived. His English improved through daily contact with Morrison, who spoke slowly and clearly, teaching ranch vocabulary, one word at a time. Cow, calf, gate, fence, water, feed. Simple words that built a bridge between languages, between enemies, between the boy Hans had been and the soldier he’d become.

Klouse watched his friend come back to life, saw color return to his face, saw him smile more, heard him sing sometimes while working old Bavarian folk songs that made the other prisoners join in, their voices carrying across the pasture in melodies that predated wars and politics. But it wasn’t just Hans who changed. All of them did. The dozen prisoners who worked regularly at Morrison Ranch began to look different, move different, speak different.

The military rigidity softened. They laughed more easily, made jokes, complained about the heat in ways that were humorous rather than bitter, began to remember tentatively that they’d once been people with interests in hobbies and dreams beyond surviving. There was Wernern, 19, from Hamburg, who’d worked in his father’s butcher shop before conscription.

He was gentle with animals despite or perhaps because of his profession, understanding the contract between humans and livestock, the responsibility to treat them well in life, even if their purpose was eventual slaughter. There was Otto, 18 from Berlin, a mechanic’s apprentice who fixed everything that broke on the ranch tractors, trucks, pumps with an intuitive understanding of machines that made Morrison shake his head in appreciation.

Otto barely spoke, but his hands were eloquent, tools extensions of his thoughts. There was Friedrich, 17, from a small village near the Austrian border, who’d loved horses before the war and found his way to Morrison’s stable, where he could curry coats in clean hooves and whisper to animals who didn’t care about nationality or politics.

They were children, all of them, playing at being soldiers because history had required it. But underneath the uniforms, they were just boys who wanted what boys everywhere wanted: safety, purpose, connection, the chance to grow up without being broken. The Morrison family treated them with a complicated mixture of weariness and kindness. Mrs. Morrison, a practical woman in her 50s, brought lunch daily, often including extra items, cookies, fruit, glasses of milk, fresh, and cold distributed without comment.

Their daughter Sarah, 16, home for summer from boarding school, watched the prisoners with curious eyes, perhaps seeing boys not so different from her own brothers. Jack Morrison himself remained professionally distant, but fair, he worked alongside the prisoners, demonstrating tasks, correcting mistakes without anger, praising good work with spare nods that meant more than elaborate compliments.

He never forgot they were prisoners, but he also never forgot they were human. By July, the heat was tremendous. Temperatures climbed past 105°. The sun a white disc in a bleached sky. The air so hot it felt like breathing fire. Work slowed to accommodate the heat early mornings until 10 evenings after 4. Nothing during the murderous midday except rest in whatever shade could be found.

During those midday hours, Klaus and Hans would sit in the barn, backs against cool stone walls, and talk, really talk, about their families, about life before the war, about hopes for after. If there was an after, if they survived long enough to go home, if home still existed when this was all over. Hans described his family’s farm with the precision of memory, polished by longing.

40 acres, 12 cows, a stream that ran clear even in summer, apple trees his grandfather had planted, a bedroom he’d shared with two brothers. The morning routine of milking so ingrained he could still feel it in his hands. Muscle memory persisting through months of absence. Klouse described Stogart city life. His father’s shop, aa watchmaker, precision work with tiny gears and springs, teaching Klaus patience and attention to detail. His mother’s garden in their building’s courtyard. Flowers somehow thriving despite the soot and noise. His

sister’s piano practice scales echoing through their apartment every evening until he decomplained about it, but now missed it with physical ache. They talked about the future tentatively as if speaking it too concretely might jinx it.

Hans would return to the farm, would work alongside his father, would eventually inherit land his family had worked for generations. Klaus wasn’t sure. The watch shop might not survive the war. Stoodgart was being bombed regularly. Everything he’d known might be rubble by the time he returned. One afternoon in late July, Morrison brought a calf into the barn and newborn, barely able to stand, whose mother had died during birthing. The calf was weak, struggling, its breathing shallow.

Morrison looked at Hans and Klouse and said something in English that Fiser translated. This one needs roundthe-clock care. Someone has to stay with it. Feed it every 2 hours. Keep it warm. I can bring it to the house. But he paused. You want to try? Hans nodded immediately. Yes, I stay. I help.

Morrison arranged for Hans to remain at the ranch overnight, sleeping in the barn with a guard posted outside. It was irregular, probably violated some protocol, but Morrison had enough local authority to make it happen. He brought blankets, extra food, kerosene lamps. Mrs. Morrison set a thermos of coffee and a basket with bread and cheese.

Klouse visited the next day, found Hans exhausted but determined. The calf was still alive, gaining strength, taking formula from the bottle with increasing vigor. Hans had named it Otto after his youngest brother, and spoke to it constantly in German, a steady stream of encouragement and promises and stories. Over 3 days, Hans nursed that calf back to health, slept in the barn, woke every 2 hours for feedings, monitored its temperature and respiration and the slowly strengthening movements that indicated it would survive. Morrison checked in regularly, brought supplies,

said little, but watched with what might have been approval, or might just have been rancher s assessment of a job being done correctly. When the calf finally stood steadily, when its eyes were clear and its coat beginning to shine, when it followed Hans around the barn like a puppy, Hans cried again, but differently this time. Not from loss, but from something gained, something proven.

He could still save things. Could still nurture life. Could still be the boy from Bavaria who cared for animals with gentle hands and patient heart. The other prisoners heard the story. It spread through camp, gaining details in the telling, becoming myth. The boy who saved the calf. The ranch that let a prisoner stay overnight. The Americans who treated them like people rather than enemies.

Each retelling added weight to the question that was growing in many minds. What were they fighting for? What had they believed? What would they believe going forward? Not everyone was happy about the Morrison Ranch assignments. There was a contingent in camp older men, true believers, those who clung to ideology because releasing it meant confronting too much, who viewed the work program with suspicion.

Collaboration, they called it fraternization with the enemy, betrayal of principles. A feldweeeble named Krueger, 35, unrepentant, organized a resistance group within the camp. They harassed prisoners who worked outside, called them traitors, threatened consequences after the war. Krueger gave speeches in the barracks about loyalty, about duty, about the eventual victory that propaganda still promised despite all evidence to the contrary.

Klaus and Hans were targeted, called farm boys, called cowards, called worse. One evening, Krueger confronted Hans directly, pushed him against a barracks wall, said things about collaboration and consequences that were thinly veiled threats. Hans looked at him with eyes that had seen too much. “I feed calves,” he said quietly. “I fix fences. I remember how to be human.

That’s not betrayal. That’s survival.” Krueger spat at his feet and walked away. But the tension remained. A fault line through the camp between those who clung to the war and those who de let it go, between men who needed to believe and boys who needed to heal. The guards were aware of the tensions. Kept watch separated troublemakers.

Major Parker gave a speech one evening translated by Fiser about the Geneva Convention, about prisoner rights, about the consequences of violence within camp. The message was clear. America would treat prisoners humanely, but would not tolerate internal conflict. Through August, the work continued.

Klaus and Hans returned to Morrison Ranch three times weekly, fell into rhythm with the place, with the animals, with the peculiar peace that came from physical labor under open sky. They knew every calf by sight now, could recognize individual animals, noticed when one seemed off or needed attention. Morrison began to trust them with more responsibility.

He’d leave them alone in pastures for hours, working without direct supervision. Once he left them with the truck keys, while he dealt with business in town, it was a test, maybe, or just practical necessity. Either way, they didn’t run. Where would they go? Into Texas? Back to Germany? Across an ocean? The question was absurd. This was their life now. These calves were their purpose.

This ranch was for these months the closest thing to home they had. September brought slightly cooler temperatures and the beginning of fall work preparing for winter, though Texas winters were laughable compared to Bavaria or Stoodgart. Klouse and Hans helped repair barns, stack hay, reinforce shelters.

The calves from spring were halfgrown now, still young enough to be playful, old enough to be confident. Hans’s favorite little Otto had thrived. The calf he’d saved now weighed 200 lb, all legs and curiosity, following Hans around like a dog, nazzling his pockets for treats. Morrison joked about it in English, words Klouse didn’t fully understand, but whose meaning was clear from tone.

That calf thinks you’re its mother. Hans smiled. Maybe I am, he said in broken English. Maybe we both need each other. Morrison nodded slowly. Maybe so. In October 1944, Klouse received a letter from his mother, the first in 9 months. It had been opened by sensors, stamped, and restamped, traveled across an ocean and a continent, to reach him in this Texas camp.

The paper was thin, the ink slightly faded, her handwriting smaller than he remembered, as if she was conserving space. She wrote about survival, about the apartment still standing despite bombings nearby, about his sister being safe in the countryside, about working in a factory now, long hours, meager pay, but work that kept her busy and fed. About his father still no word, still missing. the not knowing its own kind of torture.

She wrote, “I think of you every day. Wonder where you are. Hope you are safe. Hope you are still yourself. The war has changed everything, but I pray it hasn’t changed who you are inside. Come home when you can. Come home as yourself.” Klouse read the letter in the evening, sitting on his bunk, other prisoners talking, and playing cards around him.

The words on the page seemed to come from another world, a place that existed in parallel to this one, but couldn’t touch it, couldn’t influence it. He folded the letter carefully and put it in his pocket, carried it with him the next morning to Morrison Ranch.

During the midday break, he sat in the barn with Hans and read the letter aloud, translating the difficult parts. Hans listened silently, then pulled out his own letter received just two days before from his mother. Similar themes, survival, hope, the farm still running, but barely, with women and old men doing work that needed strong backs. His brother’s safe for now, too young yet for conscription, though that might change if the war continued.

They sat in the barn’s cool dimness. Two 17-year-old soldiers reading letters from mothers who loved them despite everything, who held hope like a fragile thing that could break if squeezed too hard. Outside, calves bellowed. Inside, dust moes drifted in shafts of light from the hoft. Han spoke first.

“When this is over, when we go home, you’ll visit Bavaria, see the farm?” Klouse nodded. Of course, and you’ll come to Stoutgart, see the workshop. If it’s still standing, they both understood the if. Understood that home was conditional now, depended on variables beyond their control. But they could plan anyway, could imagine futures that included each other, friendships that survived beyond war and captivity, and whatever came after. That evening, Klouse began writing back to his mother.

It took him three drafts to get the tone right, honest enough to be meaningful, censored enough to pass inspection, hopeful enough to not add to her burden. He wrote about Texas without mentioning where exactly, about ranch work without specifying that he was a prisoner, about calves and sunsets and the friends he’d made. About remembering who he was.

He wrote, “You told me to come home as myself. I’m trying. It’s hard to hold on to yourself in war, but I’m trying. The work here helps. Animals don’t care about politics. They just need care, and caring for them reminds me there’s more to life than the fighting. I hope the watch shop survives.

I want to learn that precision again. Want to work with my hands on something that creates rather than destroys. He wrote, “I miss Stogart. Miss the garden. Miss hearing Anna practice piano. Miss everything about the life we had before. But I’m alive, mama. I’m safe. I’m being treated fairly. That’s more than many can say. I’ll come home when I can. I promise.

He sealed the letter, gave it to camp officials for mailing, hoped it would reach her, hoped she would understand everything he couldn’t say directly. Hoped the war would end before more was taken from both of them. November brought news of eyed advances. The war was turning definitively against Germany.

Prisoners in camp followed the news through official bulletins and whispered rumors cities falling, lines collapsing, the inevitable conclusion drawing closer with each passing week. Reactions were mixed. Some prisoners were relieved, ready for it to be over regardless of outcome. Others were devastated, unable to accept defeat, clinging to belief in miracle weapons or lastminute reversals that would never come.

Klouse found he had no strong feelings either way. The war had stopped being personal months ago. It was happening somewhere else, to other people, involving decisions made by men he’d never met for reasons he no longer understood. His world had contracted to this camp, this ranch, these calves, his friend, everything beyond the felt abstract. Hans felt similarly.

“We were never really part of it,” he said one afternoon, brushing a calf’s coat until it shown. “We were just children caught in it. Used by it, but not part of it.” Klouse nodded. “When we go home, we start over. No uniforms, no more taking orders, just living. If we can remember how, Hans replied, “That was the question, wasn’t it? Could they return to normal life after this? Could anyone?” The war had interrupted millions of lives, had taken children and made them soldiers, had stolen years that should have been spent learning and growing and making mistakes that didn’t

cost lives. Could those years be reclaimed? Or were they simply gone, leaving scars that would never fully heal? In December, Camp Hearn organized a Christmas celebration. Prisoners made decorations from scrap materials. A choir formed, practicing German Christmas carols that made men weep from homesickness.

The Americans allowed a Christmas tree in each compound. Small concessions to humanity within captivity. Morrison invited Klaus and Hans to help with ranch Christmas preparations. His son was coming home on leave from the Pacific, a rare coincidence of timing and permission. Mrs. Morrison was planning a family dinner, wanted the ranch in good order, asked if the prisoners could help decorate the barn for a small celebration she was hosting for neighbors.

They strung lights in the barn reel electric lights powered by a generator glowing warm against the wood and stone. They hung garlands made from pine branches. They cleaned and organized and made the space festive in a way that felt both absurd and necessary. War continued. People died. And here they were decorating a barn in Texas for Christmas. Morrison’s son arrived 2 days before Christmas.

James Morrison, 23, Marine Cors, gaunt and holloweyed from combat in the Pacific. He stood in the barn looking at Klouse and Hans at these German prisoners his father had trusted with ranchwork, and something complicated crossed his face. Anger maybe, or confusion, or just exhaustion. Clauss and Hans stepped back, uncertain. Fiser translated an awkward introduction.

James nodded stiffly, said something in English that sounded like a question. Morrison answered, gesturing at the barn, the decorations, explaining something that made James’s expression soften fractionally. Later, Mrs. Morrison told Fischer, who told Klouse and Hans that James had been surprised to find enemy prisoners working the ranch, but more surprised to find them so young.

He’d been fighting Japanese soldiers, many of them teenagers, dying in caves and bunkers because surrender wasn’t an option in their culture. The idea of prisoners who could work ranches, who could be trusted, who could decorate for Christmas, it didn’t match his experience of war. On Christmas Eve, Morrison brought gifts to the barn where Klouse and Hans were finishing chores.

Small gifts wrapped in brown paper for Klouse, a pocketk knife with his initials carved in the handle. for Hans. A book about cattle ranching in English, but filled with pictures that needed no translation. You boys have been good help, Morrison said through Fiser. Wanted you to know it’s appreciated. Klouse didn’t know what to say. The knife was the finest thing he’d owned in years.

The gesture of personalization making it more valuable than its utility. He stammered thanks in broken English, felt his throat tighten with emotion he didn’t expect. Hans held the book like it was sacred text. Thank you. He managed. Thank you, Mr. Morrison. Morrison nodded, uncomfortable with sentiment, and left quickly.

Klouse and Hans sat in the barn, silence, holding their gifts, overwhelmed by kindness they’d been taught not to expect from enemies. That evening in the camp they attended Christmas services. The choir sang still not with voices that cracked on the high notes. Men thinking of homes they might never see again. Christmas’s past and maybe future. Klouse sang without hearing himself.

His mind on the barn. The knife in his pocket. The book under Hans’s arm. The impossible kindness of Texans who should have hated them but didn’t. After the service, Hans said quietly. This is what defeats propaganda. Not arguments, not speeches, just this. People being decent to other people. That’s what they couldn’t account for. That’s what breaks the lies. Klouse understood.

All the training, all the indoctrination, all the careful construction of Americans as enemy, it collapsed in the face at Mrs. Morrison’s lemonade. Morrison’s Christmas gifts. Sarah’s curious eyes watching them without fear. Propaganda required distance, required abstraction, required keeping the enemy as concept rather than person.

The ranch had destroyed that distance, had made Americans into individuals with names and families and kindness, had made Klouse and Hans recognize that if Americans were people, if the enemy was human, then maybe everything they’d been told was suspect. Maybe the war itself was built on lies that only worked if you never got close enough to see through them. Winter deepened. Work at the ranch continued, but slowed.

Fewer outdoor tasks, more barn work, and equipment maintenance. Klouse and Hans spent hours in the warmth of the stable, repairing tac, cleaning tools, caring for animals who needed them. The calves they’d raised in summer were yearlings now, almost full grown, no longer playful, but still recognizable. Little Otto Hans’s calf was a steer now, destined for sale eventually.

Hans knew this, understood the economics of ranching, but he dreaded it anyway. This reminder that care and commerce intersected, that animals you saved still serve purposes beyond sentiment. Morrison noticed Hans’s attachment. One evening in January as they loaded equipment into the truck he spoke to Fiser who translated that steer Otto I’m keeping him as breeding stock won’t be sold for slaughter his good bloodlines strong constitution made sense even before sentiment got involved Hans’s relief was visible immediate he nodded not trusting himself to speak Morrison

pretended not to notice busied himself self with loading. Gave Han space for his emotions. Later, Hans told Klouse he didn’t have to do that. Could have sold Otto, but he kept him because he knew it mattered to me. Because he saw and not just a prisoner. I’m just a boy who cares about animals. That’s what I mean about propaganda falling apart.

Hans continued, “When people see you, really see you. Not what you’re supposed to be, just what you are. That’s when lies can’t hold. January 1945 brought news of the Ardan offensive, Germany’s last major push, ultimately failed. February brought word of Allied advances into Germany itself.

March brought evidence of camps being liberated, of crimes being revealed, of truths that had been whispered becoming undeniable facts. The camp divided more sharply. True believers retreated into denial or rage. Others, like Klouse and Hans, felt shame and horror and a desperate need to distance themselves from a regime they’d served.

However, peripherally, still others felt numb, processing information too terrible to fully absorb. Camp officials held mandatory information sessions, showed photographs and newsre footage of what had been found in the camps. Many prisoners refused to believe it, called it propaganda, called it lies, but close watched and felt something break inside him. This was what they’d fought for. This was the government they’d defended.

These were the crimes committed in their names. He vomited outside the meeting hall, stood in the Texas night, bent over, emptying himself of more than just his stomach contents. Hans found him there, equally shaken. They didn’t speak, couldn’t speak.

What words existed for this? The next day at Morrison Ranch, they worked in silence. Morrison didn’t push conversation. Seemed to understand they were processing something beyond his direct knowledge. He gave them straightforward tasks, physical work that required focus without demanding interaction. At lunch, Hans finally spoke. We didn’t know. I didn’t know. But not knowing doesn’t erase it.

Doesn’t make us innocent. Klouse nodded. We were children. We were conscripted. We didn’t choose this. But we still He couldn’t finish. Still what? Still served. Still fought. still contributed, however marginally, to something monstrous. They sat in the shade, eating sandwiches that tasted like dust, trying to reconcile what they’d learned with who they thought they were.

The calves grazed nearby, innocent and oblivious, living in a present that held no guilt or shame or horror. Klouse envied them. Morrison approached slowly, sat with them. Fischer translated. I know you boys saw something difficult yesterday. Want you to know not your fault. You were children still are. Can’t hold children responsible for madness of men in power. Klouse wanted to believe that.

Wanted absolution. But it felt too easy. Yes, we were children, he said through Fiser. But we still pulled triggers, still followed orders. At what point does being young stop excusing what we did? Morrison was quiet thinking. Finally, you do what you can with what you’re giving.

You were given a uniform in orders and lies about what was right. You did what you thought you had to. Now you know better. Question is what you do with that knowledge. Can’t change the past. Can only choose how you move forward. It was pragmatic wisdom. Rancher’s philosophy applied to moral questions too large for easy answers.

Klouse appreciated the attempt, but doubted it was sufficient. Some things couldn’t be reconciled. Some guilt had to be carried. But Morrison continued, “I’ve watched you boys work for almost a year now. Watched how you handle animals. Watched how you treat each other. Watched you remember how to be decent humans. That matters. That’s worth something.

Won’t erase the past, but it builds toward a better future. Hans said quietly, “When we go home, what do we tell people? That we were prisoners in Texas? That we fed calves while cities burned? That we were treated kindly by enemies while our government committed horrors? You tell the truth,” Morrison said simply. “You tell what you saw, what you learned.

You help rebuild something better than what was destroyed. That’s how things change. Person by person, choice by choice. They returned to work. The conversation settled into them, not resolving anything, but providing a framework for processing. Klouse spent the afternoon mending fence, Hans grooming horses, both of them working through questions too big for immediate answers.

In April, news came of Allied forces pushing deep into Germany. By May, it was over surrender unconditional. The war in Europe ended. Camp Hearn received the news through official channels. Reactions ranged from relief to devastation. But the dominant emotion was exhaustion. It was finished. Finally, definitively finished.

Klouse felt oddly empty. No joy, no sorrow, just a strange hollow sensation, like waking from a dream you couldn’t quite remember. The war had defined everything for so long that its absence left a void nothing immediately filled. Prisoners began the process of repatriation, though it would take months, even years, to sort through millions of displaced persons and return them to countries themselves displaced. Borders redrawn, governments reformed.

Klo and Hans learned they’d likely remain in Texas through summer, possibly into fall. The Morrison ranch work would continue for now. They accepted this with relief. Returning home meant facing the ruins, facing what Germany had become, facing families and communities shattered by defeat.

Here they had calves to tend, fences to repair, purposes simple enough to understand. The delay felt like mercy. May brought spring cving again. New life arriving despite everything. Nature indifferent to human catastrophes. Continuing its cycles without pause or acknowledgement. Klouse and Hans returned to their roles as calf specialists.

Vaccinating and tagging and bottlefeeding. The routine as familiar now as prayer. One morning a calf was born with complications breach birth. Mother exhausted. a calf weak and struggling. Morrison called Hans immediately, trusted him to handle the delicate situation. Hans worked with hands that remembered every lesson from Bavaria, every hour spent with his father, learning to coax life from difficult circumstances.

The calf survived. The mother recovered. Hans sat in the grass afterward, covered in birth fluids and exhausted, and laughed. Just laughed. Pure uncomplicated relief and joy at this small triumph in a world that had seen so much defeat. Klouse sat beside him. “We’re going to be okay,” he said.

“Not today, not next month, but eventually. We’re going to remember how to live.” Hans nodded. “Yeah, yeah, we are.” They stayed at Morrison Ranch later than usual that day, helping with post-birth cleanup, checking on the new calf and its mother repeatedly. As Sunset painted the sky in oranges and purples, Morrison found them in the barn. “You boys have been good for this place,” he said through Fisher.

“Good for the animals.” “Good for me, too, if I’m honest. Reminded me that people are people regardless of uniforms. reminded me that kids are kids. Even when war tries to make them something else. He paused, choosing words carefully. When you go home, whatever that is, remember you’ve got friends in Texas.

Remember, there are people here who saw you as you are, not as enemy, not as prisoner, just as boys who grew into good men in spite of terrible circumstances. Klouse felt tears threaten Mr. Morrison. I He couldn’t continue. Switched to German, letting Fiser translate. Thank you for everything. For trusting us with your animals, for treating us like people. For showing us that humanity persists even in war.

We won’t forget, Hans added, the calves. All the animals we helped. They saved us as much as we saved them. Gave us purpose. gave us back pieces of ourselves we thought were lost. We owe this ranch more than we can repay. Morrison waved off the sentiment. Uncomfortable, but pleased. You worked. You earned your keep.

That’s how it works. But yes, glad we could help. Glad you could help us. They drove back to camp in the evening light, quiet, thoughtful. The war was over, but they were still prisoners, still waiting for bureaucracy to process them, still existing in this strange liinal space between conflict and peace. But something had shifted.

They’d survived, not just physically, but internally. They dereained themselves or rediscovered themselves through care for animals and honest work, and the kindness of Texans who dechosen to see them clearly. Klaus Vber was repatriated to Germany in November 1945. He found Stogart in ruins.

His mother’s apartment miraculously standing in a neighborhood that was otherwise rubble. His father never returned from the Eastern Front, declared missing, presumed dead. His sister had married a returning soldier, was pregnant, building a life in the fragments of what remained. Klouse worked various jobs, construction, cleanup, manual labor, rebuilding a country. He saved money.

In 1948, he enrolled in technical school, studied watchmaking like his father, learned the precision work that had once been family trade. By 1950, he’d opened a small shop, nothing like his father’s original, but functional, serving a community hungry for normaly. He wrote to Hans regularly.

Letters took weeks to travel between Stitgart and Bavaria, but they maintained connection, anchored each other as they navigated postwar Germany. Hans had returned to his family’s farm, found it damaged but operational, his mother and brothers having kept it running through sheer determination.

He threw himself into farm work, expanding the dairy operation, introducing techniques he’d learned in Texas, better breeding practices, improved calf care, modernization, and increased productivity. In 1952, Klouse visited Hans in Bavaria. The farm was beautiful, 40 acres of rolling hills. The stream Hans had described running clear apple trees in full bloom. They spent a week working together. Klouse helping with spring chores.

Hans showing off improvements he’d made. Both of them marveling at having survived to see this moment. They talked about Texas, about Morrison Ranch, about calves and fences and the hot summer sun that had baked them while they worked, about learning to be human again in captivity, about kindness from enemies, about propaganda dissolving in the face of simple decency.

Hans had kept the book Morrison gave him, a cattle ranching guide, now worn from use. Pages dogeared, a treasure he’d brought across an ocean. Klouse still carried the pocketk knife, its handle smooth from years of use, initials worn but visible. They wondered about the Morrisons, whether the ranch still operated, whether Jack Morrison still raised Herfords, whether little Otto Hans’s saved Cafad sired the strong bloodlines Morrison predicted. But communication was difficult in those years.

The distance between Texas and Germany was more than geographic. It was temporal, emotional, a gap between lives that had intersected briefly before diverging permanently. In 1956, Hans married. A local girl whose family had a neighboring farm. They combined properties, built a new house, started a family. His first son was born in 1957. He named him Otto after his brother, after his calf, after a reminder that life persists. Klouse married in 1959.

a woman who worked in the shop next to his, a seamstress with quiet dignity and practical wisdom. They had two daughters. Klouse taught them watchmaking basics, passed down precision and patience, tried to give them skills that created rather than destroyed. Neither of them talked much about the war, not because they’d forgotten, but because the world wanted to move forward, wanted to leave that darkness behind.

Germany was rebuilding, reinventing itself, trying to become something other than what it had been. Veterans, even boy soldiers like Klouse and Hans, carried their experiences privately, processing trauma in silence, letting time create distance from events too painful for constant examination. But June 6th D-Day anniversary, they always marked it.

Klaus would go to his shop early, sit with a cup of coffee, remember the beach, the bunker, the Americans coming ashore in waves that couldn’t be stopped. Hans would walk his property, visit his cattle, remember Texas heat and the calf he’d saved the moment he de cried in a pasture because touching an animal had reminded him he was still alive inside.

In 1984, on the 40th anniversary of D-Day, journalists sought out German veterans for perspectives on the invasion, Klouse was interviewed, gave measured responses about courage and defeat, about learning humanity from enemies. The article mentioned his time in Texas, though without detail. A copy of that article through channels circulating in expatriate communities reached Texas, reached Fredericksburg specifically, a town with deep German heritage, reached someone who remembered. In 1985, Klouse received a letter from America

from Sarah Morrison Fletcher, Jack Morrison’s daughter, writing on behalf of her aging father. The letter said her father had seen the article, remembered Klouse and Hans, wanted them to know the ranch still operated, and he often thought about those German boys who dew worked so hard and cared so deeply for the calves.

The letter said, “My father wanted you to know little Otto lived a long life. Sired over 200 calves before passing in 1960. Strong bloodlines just like dad predicted. Every calf from that line carried something forward. Your friend Hans’s care mattered. Made a difference that lasted generations. Klouse wept reading it. Called Hans immediately read the letter over crackling phone lines.

Hans wept too, not from sadness, but from completion. That circle closed. That piece of their past acknowledged, remembered, honored. They wrote back together, composing a joint letter that took three drafts to get right. They thanked the Morrisons, described their lives, said the ranch had saved them in ways beyond the physical.

Said they built good lives, raised families, contributed to rebuilding a better Germany, and all of it traced back in part to those months in Texas learning to be human again. Jack Morrison died in 1987 at 83 on his ranch surrounded by family. Sarah wrote to Klaus and Hans with the news said her father had spoken of them in his final days.

Said he dee been proud of the boys who de remembered how to be gentle in the midst of war. Hans Vber died in 1993 at 68 of heart failure. Klouse attended the funeral in Bavaria, stood by the grave of his closest friend, remembered everything they’d shared, desert and ocean, bunker and ranch, calves and kindness, survival and rebuilding. Klouse lived until 2003, dying at 78 in Stutgar, surrounded by daughters and grandchildren, having built a life of precision and care from the fragments war had left.

In his final weeks, he talked about Texas, about heat and dust and endless sky, about a calf he’d held that had cried like a child, about learning that enemies could be kind, that humanity persisted even in captivity, that sometimes the worst circumstances revealed the best possibilities. His daughters found the knife after his death Morrison’s gift, worn but treasured.

They found letters from Hans spanning five decades. They found a photograph, black and white, creased and faded, showing two teenage boys in faded uniforms standing in a Texas pasture, squinting at the camera, each holding a calf, their faces holding something that might have been hope or might have been the beginning of healing.

The photograph had no date, no labels, just two boys and two calves and an empty horizon behind them. But it told the story their children and grandchildren would struggle to understand about how war makes soldiers of children. And how sometimes, if they’re very lucky, children find their way back to childhood, even in the midst of captivity, even in enemy territory.

Even when everything suggests that innocence is lost forever, the Morrison Ranch still operates today, run by Jack Morrison’s grandchildren. They keep a small museum in the renovated barn photographs of the camp, artifacts from the era, a section dedicated to the German pose who worked there.

Among the displays is a worn book about cattle ranching donated by Hans Vber’s son and a letter from Klaus Vber explaining what that time had meant, how those calves had saved them. Tourists visit, school groups learn the history. The story persists not as propaganda or myth, but as documented truth boys from Germany and ranchers from Texas, finding common ground in care for animals, breaking down barriers through work and kindness, proving that humanity can persist even when politics tries to erase it. Every spring when new calves are born on Morrison Ranch, someone remembers.

remembers the German boys who’d cried over newborn calves because it reminded them they were children. remembers the Texan rancher who’d seen past uniforms to the humanity underneath. Remembers that even in the worst darkness, even in war’s absolute dehumanization, there are moments of light that prove something essential survives.

This is what Klaus Vber and Hans Vber carried their whole lives. Not just memories of war, not just trauma and survival, but this small perfect truth. They’d been prisoners. They’d been enemies. They’d been children dressed as soldiers. But in a Texas pasture in 1944, holding cows that needed them, they’d remembered who they really were. And that remembering had carried them home.